Tens of thousands of people refused to work in protest against unequal pay and gender-based violence (Picture: AP Photo/Arni Torfason)

It was eerily quiet on the suburban streets of Iceland on October 24, 2023.

Schools weren’t open, swimming pools closed and several banks shut early. That was because the majority of Iceland’s women were not at work or looking after children; they were gathered in downtown Reykjavík and other cities and towns across the country.

The 100,000-strong group, made up of women and non-binary people, had taken part in kvennafrí [Women’s Day Off in English].

What is Women’s Day Off?

Women’s Day Off, known as kvennafrí is the day that the women of Iceland staged a protest to put an end to unequal pay and gender-based violence. They refused to work, cook and look after children for a day.

In the morning, all-male news teams had announced shutdowns across the country with buses delayed, hospitals understaffed and hotel rooms uncleaned.

By afternoon, a huge group gathered on Arnarhóll, a hill in Reykjavík city centre, to wave signs and sing feminist songs such as ‘Áfram Stelpur (Onward Girls.) The song includes lyrics which translate to:

‘Now women mass together and carry signs of freedom; the time has come, let’s all stand hand in hand and firmly stand our ground. Even though many want to go backwards and others stand in place; we will never accept that.’

Why are women in Iceland protesting?

Finnborg (right, with sign) at the 2023 Women’s Day Off (Picture:Finnborg Salome Steinþórsdóttir)

On the day of the protest, gender studies researcher Dr. Finnborg Salome Steinþórsdóttir stood nervously outside the University of Iceland. She had posted in Facebook groups and sent out emails about the event to her colleagues. Yet, the mum-of-one was paranoid no-one would heed her call.

Finnborg, 39, tells Metro: ‘I thought “this could be embarrassing, what if no-one turns up and I’m there alone?.” But then more and more people started to arrive. We had 1,000 people alone from the university in the end. I remember taking a photo as we walked towards downtown Reykjavík – we took up the entire street! There was a sense of solidarity in the air.’

Women on average earned 21% less than men in 2022, according to Statistics Iceland, and a third worked part time due to childcare commitments. Meanwhile, 40% had experienced gender-based assault or harassment. The group of protesters wanted to take aim at both these key issues.

A huge group gathered on the grassy Arnarhóll hill armed with signs and banners (Picture: AP)

The group also wanted to tackle the wider undervaluation of women’s jobs; such as the gender segregation between traditional ‘female’ jobs like care and education compare to ‘male’ jobs and expectations in finance and business.

Prime Minister Katrín Jakobsdóttir was among those who refused to work for the day as well as Iceland’s First Lady Eliza Reid.

Finnborg carried a sign which read ‘actions immediately’ in Icelandic. Slogans such as ‘Kallarðu þetta jafnrétti?’ [You call this equality?] were emblazoned on the placards held by others around her.

As the protestors marched around Tjörnin lake and made the streets of Reykjavík their own; they walked in the footsteps of revolutionaries; after the first monumental Women’s Day Off in 1975.

To view this video please enable JavaScript, and consider upgrading to a web

browser that

supports HTML5

video

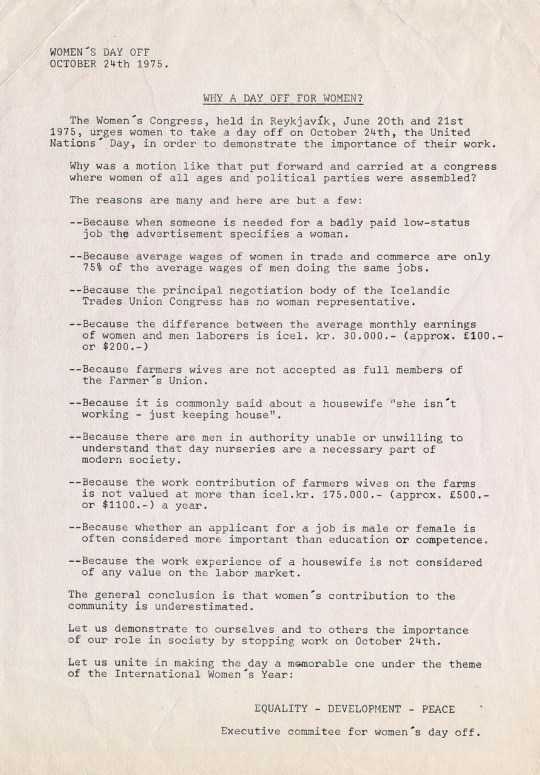

What happened in Iceland in 1975?

Women in Iceland could vote, get an education and run for public office by the 1970s. But they were still hugely underrepresented in the Parliament, only making up 0-5% of politicians. As a result, a movement called the ‘Red Stockings’ entered society in 1970.

Along with similar groups, the Red Stockings decided to organise ‘something amazing’ for the United Nations ‘Women’s Year’ in 1975. Women would down tools and stop working in a bid to get men to listen to their concerns. They named the protest ‘Women’s Day Off’ instead of ‘Women’s Strike’ to not risk women being fired by employers. Stickers with ‘Women’s Day Off’ were printed and appeared on clothing, handbags, walls and windows, as thousands of women put Friday October 24, 1975 in their diary.

They included Kristín Ástgeirsdóttir, a 22-year-old history student at the University of Iceland. She’d been brought up in Vestmannaeyjar, a fishing community in Iceland, by her nurse mother and writer father.

‘It was like a wave,’ Kristín tells Metro. ‘Women would ask each other “are you going?” at work or on the street. The word spread. On the day, around 2pm, we started streaming down the streets to this meeting. To see all those women, to feel the energy, it was fantastic.’

The reasons which spurred the very first Women’s Day Off protest back in 1975 (Picture: Kvennasögusafn – Women’s History Archives)

Kristín, 24, in 1975 and (right) on stage at the Women’s Day Off in 2023 (Pictures: Kristín Ástgeirsdóttir)

Women gave speeches and sang songs as the day passed and, at one point, a brass band performed the theme tune to ‘Shoulder to Shoulder’, a BBC series about the Suffragette movement which had been popular in Iceland. It was estimated that 90% – 30,000 – of the nation’s women had taken part in the demonstration.

Meanwhile, men took children to work or remained home to care for them. According to local reports, foods like Bjúga – a smoked sausage which doesn’t require cooking – ran out in many supermarkets. Radio presenters called households in rural towns and villages to ask if women were taking part in the protest and – for the most part – had the phone answered by men who confirmed this was the case. Fish factories were forced to close since so many of the workers were female and telephone switchboards were unmanned.

The Women’s Day Off was referred to as ‘long Friday’ by some fathers.

Did the Women’s Day Off change anything?

The 1975 march galvanised a generation of women in Iceland.

By 1983, women gained 15% of parliamentary seats compared to just 5% a decade before. Vigdís Finnbogadóttir came to power in Iceland in 1980, becoming the world’s first democratically elected female president.

At the time, Kristin was a journalist at a radical left-wing newspaper. She recalls from this time: ‘Seeing and hearing the discussion around Finnbogadóttir – she was divorced, she had adopted a child, she had had cancer – made me so angry.

‘Some men thought it was impossible for a woman like that to be in power. But she did win and that was fantastic, it meant a lot for the next generation of women to see a woman in this top position.’

Vigdís Finnbogadóttir made history in 1980 when she became the world’s first woman to be democratically elected president (Picture: Pressens Bild/AFP/Getty Images)

Finnbogadóttir was president until 1996; both Finnborg and Valgerður grew up with her in power. Further history was made in 2009 with the election of Jóhanna Sigurðardóttir as Prime Minister of Iceland – and the world’s first openly gay PM.

Meanwhile, Women’s Day Off protests continued, albeit on a smaller scale.

In 2010 for example, many women packed their bags and left work at 2:25pm. This was to highlight the gender pay gap and how the time they essentially stopped getting paid compared with men’s earnings. Similarly, in 2016, Icelandic women left work at 2.38 p.m., and in 2018, women left work at 2:55 p.m.

‘A convention of clout chasers’

Iceland has been ranked as the world’s most gender-equal country 14 years in a row by the World Economic Forum (Credits: Shutterstock / Petur Asgeirsson)

Without today’s social media or rolling news, coverage of the 1975 march may have been confined to local newspapers. But due to one very fishy situation, that was not the case.

In 1975, Britain and Iceland were embroiled in the third ‘Cod War,’ a bitter feud over fishing rights. Journalists from Britain had been in Reykjavík for a crunch meeting on October 15 and several decided to stay on and cover the Women’s Day Off march.

‘Icemaidens give their men the freeze’ and ‘Chaos reigns as Iceland’s women go on strike’ were among the headlines in the British press. On October 24, 1975, the Coventry Evening Telegraph reported ‘men, who initially treated the strike as a joke, began to take the point.’

In Iceland, there was a divide in coverage based on the politics of each paper, Valgerður Pálmadóttir – an academic at the University of Iceland – explains. The daughter of a history teacher father and a gender studies university lecturer mother, there were plenty of conversations about feminism around her dinner table growing up in Reykjavik.

Valgerður has researched the history of movements like the Women’s Day Off protest (Picture: Valgerður Pálmadóttir)

There was a sense of ‘belittlement’ in some coverage of the 1975 march, Valgerður’s research of the gender movement has found.

‘Newspapers with connections to the political left tended to present the event’s significance in political terms as a serious women’s and class struggle,’ Valgerður, 40, tells Metro. ‘They also persisted in naming the action a “strike” rather than the less confrontational “day off.”

‘In contrast, newspapers more associated with the political right focused on the joyous and festive atmosphere of the “day off” as a celebration of women and highlighted the dignity of Icelandic women. This depoliticised the message. A third framing that was common in the Icelandic coverage – mostly in non-aligned newspapers – took a humorous perspective, sometimes including belittlement. But across the spectrum, the Women’s Day Off was regularly framed as historic and unique, with a hint of national pride that Iceland had made world news.’

Meanwhile, the story of the 2023 mass walk-out was covered by news outlets across the world, from the Guardian to CNN. The event had marked the first full-day women’s strike in Iceland since 1975.

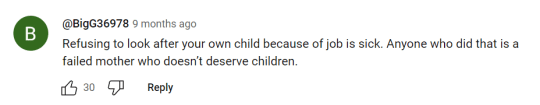

Comments like the above were left on news reports about the protests in Iceland (Picture: YouTube)

But a segment by WGN-TV, a news channel based in Chicago, Illinois, garnered a wave of negative responses on YouTube.

User @WillmobilePlus commented: ‘The biggest convention of clout chasers on Earth’ while @johncross2516 added: ‘All the women at rally, Heaven has come at last, the men can have some peace.’ @mrbloxpie4221 wrote: ‘You’re telling me these people refused to take CARE OF THEIR OWN CHILDREN JUST TO PROVE A POINT? That’s just horrible and the kids deserve better mothers.’

Finnborg sighs sadly in response. ‘Misogyny is not in our imagination, it’s visible in the comment section and reflect the society we are in,’ she says.

What’s next?

Feminist Urður Bartels gives a speech at the 2023 Women’s Day Off (Picture: AP)

While feminists in Iceland vow to keep fighting, plans are underway for a whole year of action in 2025 to mark 50 years since the 1975 kvennafrí.

But Finnborg is keen to stress that future events are seen as a ‘fight’, not simply a ‘celebration.’

She adds: ‘We want to avoid the Women’s Day Off becoming like a festival. In 2023, we had lots of politicians attend which had symbolic importance as these are the people who can change things. But some had very right-wing and harmful policies on public spending and migration, which is not good for women or marganilised people.’

‘It feels that the feminist struggle is much more robust,’ Valgerður adds.

‘It is more mainstream and not concentrated on a few individuals but now a broad and diverse movement. Despite the fact that the gender wage gap and gender-based violence persists, we have also come far since the 1990s and early 2000s. There are, for example, many more ways to express oneself and one’s gender identity today than 20 years ago.’

Women and non-binary people took part in the 2023 Women’s Day Off with more events planned in 2025 (Picture: AP)

Kristín has been a student, a journalist, a politician, an activist and an academic throughout her life. She is now 73 and part of the group which is organising 2025’s year of action. What keeps her fighting? What stops her from giving up?

More Trending

Kristín pauses and takes a sip of tea out a Moomin mug [creator Tove Jansson is a feminist icon to many in Nordic nations] before answering.

‘I was brought up with the belief that our role in society is to make it better,’ she explains.

‘It is important we stay awake. We see how easy it can be for men to take rights away; we have seen that in Afghanistan, in Russia. We can’t give up or forget the history of women and the history of feminism. If we learn from our history, we know what we are dealing with in our future.’

To read more about the Women’s Day Off movement, click here.

Do you have a story you’d like to share? Get in touch by emailing Kirsten.Robertson@metro.co.uk

Share your views in the comments below.

MORE : I was raised in a POW camp and this is what I remember most

MORE : I travelled 5,000 miles to live as a monk for a year

MORE : Girls so worried about hygiene they’re stopping their periods on purpose

latest news, feel-good stories, analysis and more

This site is protected by reCAPTCHA and the Google Privacy Policy and Terms of Service apply.