On a cloudy day in late October, Alyssa Shiel crouched on a narrow strip of grass between the curb and the sidewalk of a neighborhood in inner Southeast Portland, plunging a small syringe-like probe into the soil.

Shiel, an Oregon State University professor, and graduate student Ashley Sutton collected samples from this strip and others in the area, targeting the ground around old telecommunications cables hanging between utility poles.

In an earlier study, Shiel found that those cables — essentially, lead tubes with a bundle of copper wires running inside — are leaching lead onto plants and soil and contributing to elevated lead levels in many residential Portland neighborhoods.

She is now seeking to understand whether they are a significant if overlooked source of a toxic metal — much like leaded gasoline, lead paint and lead-contaminated foods — that even at very low levels can cause irreversible neurological damage, especially in children.

Shiel is at the national forefront of research into the cables’ contamination risks as communities and government regulators across the country grapple with newly raised concerns about an expansive network of the toxic cables, trying to figure out where they are, just how dangerous they are and whether or how to get rid of them.

READ MORE: How to check for lead-sheathed cables

Lead does not break down over time and so accumulates in soil, but not much federal testing or scientific research has focused on the potential risks coming from lead-sheathed cables.

Among the unknowns: how much lead is present underneath the sheathed cables, whether the lead is on the surface or has settled deeper and whether it has migrated into yards and other nearby spaces.

Telecom companies have maintained the lead-sheathed cables pose no danger and have yet to disclose their locations. Because so little is known, state and federal public health officials do not have a handle on how to regulate the cables, whether to remove them and who should pay the cleanup costs.

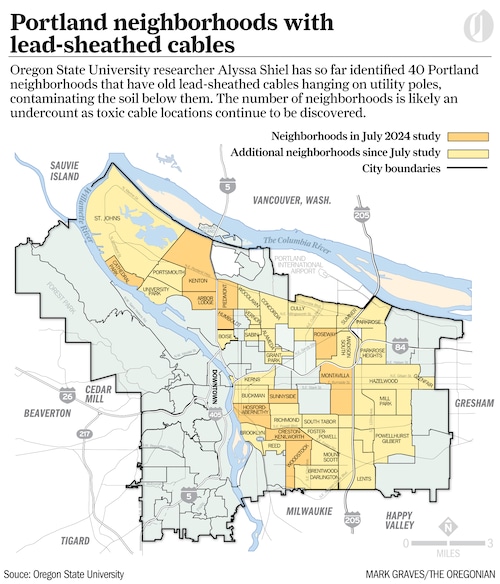

In Portland, Shiel is trying to both map the cable locations and understand their risks. She has found the cables in nearly half of Portland’s neighborhoods.

“We’re really concerned about the levels in the soil because that’s the most likely route of exposure, especially for kids,” Shiel said. “The disturbance of lead-contaminated soil poses a risk of inhalation for people. And kids play in the soil, they eat the dirt, they get their hands dirty and put their hands in their mouths.”

Oregon State University Alyssa Shiel (left) and OSU grad student Ashley Sutton use a small syringe-like probe to gather soil for testing beneath lead-sheathed cables in inner Southeast Portland. The cables have emerged as a new source of environmental lead, but their risk to human health remains unclear. Dave Killen / The Oregonian

MYSTERIOUS SOURCE

Shiel, an environmental geochemist, had been studying metal contaminants for years. She had constructed global records of lead emissions spanning the history of early human mining and industrial activity using ice and lake sediment records and had traced lead pollution from large industrial sources such as metal smelters and mines.

After the U.S. Forest Service in 2016 published an assessment of chemicals in tree moss, identifying high concentrations of several heavy metals in neighborhoods throughout Portland, Shiel noticed hotspots of lead in neighborhoods with no known industrial areas.

The moss study had helped pinpoint two glass manufacturing plants as the source of elevated cadmium and arsenic. Concerns over the pollution drew a massive outcry from residents and political leaders, leading to a new state program regulating toxic air emissions from commercial and industrial facilities.

But researchers didn’t know what to make of the elevated lead. So Shiel teamed up with Forest Service researcher Sarah Jovan to try to uncover its source.

The two selected 70 of the 350-plus original moss samples for lead isotopic fingerprinting, a technique that identifies the composition of lead and can pinpoint the provenance of lead pollution from a menu of potential sources.

The fingerprinting revealed emissions from historical leaded gasoline use as the primary source across the city. But in some locations with elevated lead levels, it also revealed the presence of lead that matched no source on the menu.

The scientists explored various possibilities – demolitions of houses or old industrial sources, for instance – but it was not until summer 2023, when the Wall Street Journal published an investigation about lead-sheathed telecom cables leaching into the environment, that a hypothesis began to form.

Shiel went back to the residential areas with the highest lead levels to confirm her hunch.

“That story led us to look up at these sites. And when we looked up, we saw the old lead telecom cables,” she said.

Lead-sheathed cables, suspended from support wires with loops, were installed across the U.S. starting in the late 1800s and were phased out in the 1960’s. But many remain throughout Portland, leaching toxic lead onto plants and soil. Their risk to public health is still unclear. Dave Killen / The Oregonian

Shiel checked most of the sites from the moss study for lead cables, including all 70 of the sites selected for the isotopic fingerprinting as well as sites in older parts of Portland and those with elevated lead levels.

She collected more than three dozen additional moss samples in neighborhoods with lead-sheathed cables and compared all of the results with moss samples from rural forested areas that the Forest Service had collected.

The results were not a surprise. She found lead levels in Portland were 19 times higher on average than in rural areas, largely the result of historical leaded gasoline use.

But when lead cables were present, the difference was even more stark: The highest lead concentration found in moss near a lead cable was 100 times that of moss from nearby residential sites without lead cables and nearly 600 times that of rural moss.

The study suggested the leaching of lead from the sheathed cables was responsible for the elevated lead levels in older neighborhoods.

TELECOM LEGACY

Lead-sheathed telecom cables had been installed across the U.S. between the late 1800s and the 1960s as part of Bell System’s regional telephone network.

Some were eventually removed and replaced with plastic-sheathed cables or fiber-optic ones, while others remained, inherited by modern companies such as AT&T, Verizon, Century Link and others.

The Wall Street Journal found records of more than 2,000 lead-sheathed cables spread throughout the U.S., strung on poles, buried underground or under water. The newspaper tested sediment and soil samples at more than four dozen locations and found levels of lead exceeded safety recommendations set by the Environmental Protection Agency, which is responsible for regulating lead.

The story also revealed that telecom companies had known for many years about the lead-covered cables and the potential risks of exposure to their workers – though they have maintained the cables are not a public health hazard or a major contributor to environmental lead.

Environmental and public health regulators, on the other hand, seemed unaware of the problem.

Following the investigation, legislators and regulators pushed to get the locations of lead-sheathed cables and demanded federal officials determine public health risks. But telecom companies, which own the cables, have declined to release their exact locations.

In court filings, AT&T estimated that lead-sheathed cables represent less than 10% of its 2 million miles of sheathed cables, or nearly 200,000 miles across the U.S., with most of them still in active service. They include aerial, underground and underwater cables. The lead-sheathed cables also make up roughly 15% or 81,000 miles of Verizon’s 540,000-mile copper network, according to New Street Research, a financial analyst firm focused on the telecommunications sector.

Other companies also own cables with lead sheathing – though they have not revealed how many miles – and some of the cables are abandoned. New Street Research estimated it would cost $4.4 to $21 billion for telecom companies to remove the toxic cables.

And it is still unclear who, exactly, could compel them to remove them.

U.S. Sen. Ron Wyden was one of a dozen senators who last fall wrote a letter to the Federal Communications Commission asking the agency to provide lead-sheathed cable locations and other related information.

The agency responded last December that it “lacks statutory authority … to regulate the particular materials that carriers have used in facilities within their existing networks” and has no authority over lead cleanup.

In Oregon, the Public Utilities Commission has been working to determine the locations of lead-sheathed lines owned by the telephone companies it regulates, the status of the lines – whether they are in use or abandoned – and the companies’ plans for replacement or removal of the lines, said the commission’s spokesperson Kandi Young.

“The Oregon Public Utility Commission staff is in the information gathering phase on this issue that may, once evaluated, support a more formal PUC investigation,” Young said via email. “There is not a specific deadline for the information gathering phase. Once staff has obtained necessary information from the utilities, we will evaluate that to determine next steps.”

Young said the commission has issued information requests to Ziply (formerly Frontier Communications) and Lumen, which consists of CenturyLink QC, CenturyTel, CenturyTel of Eastern Oregon. Ziply owns the former Verizon cables in the state while Lumen owns the former AT&T cables.

40 NEIGHBORHOODS

Shiel had identified 11 Portland neighborhoods with lead-sheathed cables when she published her research this summer in the peer-reviewed scientific journal Nature Communications Earth & Environment.

Since then, she has realized the problem is more widespread.

Though the process is laborious given the dearth of information from telecom companies, she has worked to map the cables across the city – some she runs into in person, others she finds via Google Street View and still others are reported to her by local residents.

“When I’m driving around in my everyday life, I can’t help but look for these cables,” she said. “What strikes me is that I’m finding them all over now that I know how to look for them. The number of people that could be impacted concerns me.”

Her list has now grown to a total of 40 of Portland’s more than 90 formally recognized neighborhoods, most of them on the east side – and she expects it to grow. She also has found lead-sheathed cables in Gresham, Bend, Corvallis, Albany, Newport and McMinnville, among others.

“We are getting new data all the time,” she said.

Mark Graves, The Oregonian

Shiel is also working with a colleague to develop an A.I. algorithm to identify lead-sheathed cables using Google Street View maps.

Her most immediate focus: to evaluate how lead leaches from the cables and whether it poses a significant risk to human health.

She is collecting surface soil samples in six Portland neighborhoods with the lead-sheathed telecom cables, prioritizing sampling in areas with schools, daycares, bus stops and gardens near or underneath the cables.

To see whether the lead is migrating, she is sampling at 1-foot intervals from the cables when possible. Soils from across the street are also collected for comparison at each site.

Oregon State University professor Alyssa Shiel (left) and Ashley Sutton, a grad student at OSU, gather soil for testing beneath lead-sheathed telecom cables in Southeast Portland on October 29, 2024. Shiel is working to understand the cables’ potential health risks.Dave Killen / The Oregonian

The samples will be measured for lead concentrations and isotopic compositions at an Oregon State lab. Shiel will compare the measured lead levels with U.S. Geological Survey background levels and federal screening levels for lead contaminated soils.

If lead is present at high levels, potential risks would depend on the age and health of the person exposed, the frequency and duration of exposure and whether it occurred through inhalation, ingestion or skin contact — with exposure at the highest when lead is breathed in.

She plans to publish the results next summer.

NO IMMEDIATE THREATS?

Federal soil testing conducted underneath sheathed cables in New Jersey and Pennsylvania last year gives a hint of what she might find.

In the wake of the Wall Street Journal investigation, the Environmental Protection Agency launched its own investigation into the impacts of lead-sheathed cables.

Last year, the EPA’s investigation of soils from West Orange, New Jersey and from the Pennsylvania towns of California and Coal Center found multiple soil readings with lead above the safety guideline for children at the sites, including levels up to 3,400 parts per million of lead, well beyond the EPA screening level of 400 parts per million (in January, the EPA screening level was lowered to 200ppm).

Despite the elevated levels, the EPA concluded no emergency response was needed at the sites. It said “there are no immediate threats to the health of people nearby” because the sites were either not used by children or had grass cover, which the agency said would prevent lead from becoming airborne.

But the agency continues to investigate long-term impacts of lead-sheathed cables. It also has required major telecom companies to provide results of inspections that the companies have undertaken and of sampling results and data they have gathered.

The individual telecom companies and the industry’s trade association, USTelecom, have maintained the cables do not pose a risk.

“We have not seen, nor have regulators identified, evidence that legacy lead-sheathed telecom cables are a leading cause of lead exposure or the cause of a public health issue,” USTelecom has said on a website that represents the industry on the issue.

The EPA has done no testing in Oregon. Shiel said the risks in Portland and other parts of the state may be different because the climate differs from the East Coast. For one, grass in Portland goes dormant every summer, which means children playing under or near the sheathed cables could be disturbing bare soil, kicking up and inhaling the lead.

Also, Portlanders are avid gardeners, with some cultivating raised beds to the curb, just underneath the lead cables, Shiel said, a phenomenon she witnessed at some of the sheathed cable locations across the city.

The Oregon Health Authority told The Oregonian/OregonLive that it is aware of Shiel’s research and this summer shared it with its workers and has added lead-sheathed cables to its list of potential sources that its staff should check for when conducting child lead exposure investigations. The agency does not regulate lead sources, except for lead-based paint activities and tracking child lead exposure and poisoning.

Removing the cables may prove complicated. A proposed class-action suit by utility employees who worked with or near the lead-covered cables alleges they may have been exposed to high levels of lead contamination.

But even if all the cables were to be removed, there is still the question of what to do with the contaminated soil, Shiel said.

“Lead doesn’t go anywhere,” she said. “The soil below has been receiving lead from those cables in some locations for 100 years or more. And if you wanted to get the lead out, what you would actually have to do is remove or remediate that soil.”

In the meantime, Shiel encourages everyone to look up and see if any lead-sheathed telecom cables are hanging overhead. And to keep kids and gardens away from them until more is known — or test them both for lead.

— Gosia Wozniacka covers environmental justice, climate change, the clean energy transition and other environmental issues. Reach her at gwozniacka@oregonian.com or 971-421-3154.

Our journalism needs your support. Subscribe today to OregonLive.com.