Though I have spent many years as a journalist, my other profession as a teacher is the closest to my heart; when I studied biology and its teaching methods at university, I knew that I would become one. I became excited about getting a job in education, but unfortunately I was not lucky at first—because I live in Gaza, that besieged area on which Israel has imposed many sanctions that have led to a reduction in job opportunities and an increase in the unemployment rate. But I felt I had to meet this challenge that was inside me: I would become a teacher; I would practice this profession.

I started teaching at home with private lessons. I used to work 12 hours a day to teach students, in both the mornings and the evenings. Then, five years ago, I got the opportunity I was waiting for: I became a science teacher for the fifth and sixth grades at the Rosary Sisters School in Gaza City. Those years held the happiest moments of my life—a lively routine full of giving, passion, and love.

Waking up early, at 6 a.m., seeing the streets filled with students from all the schools, the traffic police stopping cars so that the students could pass safely—it made me happy. I live in the southern Gaza Strip, and the school in Gaza City is in the north. It took me about half an hour to get there every day; in those 30 minutes I would look out the window a lot and see these students in different types of school uniforms, and watch their conversations and their laughter with one another. The streets were so vibrant during the school year.

When I arrived at school, the students would run toward me to hug and welcome me, offering many nice comments on my daily appearance. I was interested in being an elegant teacher because I thought it would help my students love my subject. I felt that the student needs to love their teacher to love the material, especially when it comes to science. It is not a simple subject and often requires long explanations. These students must accept this flood of information from someone they love.

Our favorite place at school is the science lab. More than any other place, it used to unite the students and teachers as colleagues when we conducted our many scientific experiments together. Unfortunately, we had an appointment for classes in the lab on Oct. 8, 2023; the war deprived us of it.

Wars are the biggest enemy of all students. When we heard the sounds of warplanes roaming the skies of Gaza, we were worried. The students were sitting under the chairs, and we were calming them down by telling them that there would be no bombing. Many of them asked us repeatedly if there might be a war in Gaza. Then each one of them would start talking about their experience in previous wars and express their intense hatred for war and destruction. I tried comforting them by telling them that there would be no more wars, and that what happened in the 2021 war would not be repeated. Unfortunately, we lived through a difficult conflict then. The school was severely damaged, and my science lab was, too. We returned for the next year later than other schools. When the current war started, the administration had not even finished restoring and repairing the school from the previous one.

The students expressed their hatred for the war from that first moment, complaining that it would force them to stay at home and deprive them of school for several days. It was so nice last year; I felt that these children had very mature minds. They were following the news a lot. Every morning they would express their concern about the tragic events in Jerusalem and the West Bank and say that they did not want this war to move to Gaza. We all wanted to continue our lives in peace. They wanted to finish the school year without a war, or anything political that would hinder their studies.

On Oct. 5 last year, it was a Thursday. We put together a work plan for Monday, because Friday was an official holiday. Saturday, Oct. 7, was an annual holiday for our school that commemorates its founding. Sunday, Oct. 8, was the official holiday for Christian schools in Gaza, and we were supposed to return to school on Monday. We were very happy to have three days off, because we had just finished the first month’s exams and we needed a rest. But that Saturday, Oct. 7, at about half past 6 in the evening, we heard the sounds of rockets being launched. Many of my students sent me messages asking me: What is this? What is happening? After about two hours we understood what had happened in Israel and what was happening in Gaza, and it was all very difficult and tragic.

That first week, studies were suspended in all of Gaza, and the students have not been back to school since. The 2022–2023 school year ended without the students returning; instead they spent their time in tents, displaced and homeless, far from their homes. Many of them, though, did leave their homes carrying their school bags, and have spent the past year studying without a teacher. The families are in a state of great sadness, and many believe the Israeli army is carrying out a policy of enforced ignorance—depriving students of studying, destroying their schools and homes, and killing hundreds of students and teachers.

Thousands of students have been killed in Gaza. Five hundred schools and universities have been destroyed. This fall, more than 160,000 students did not return to school for the second year in a row.

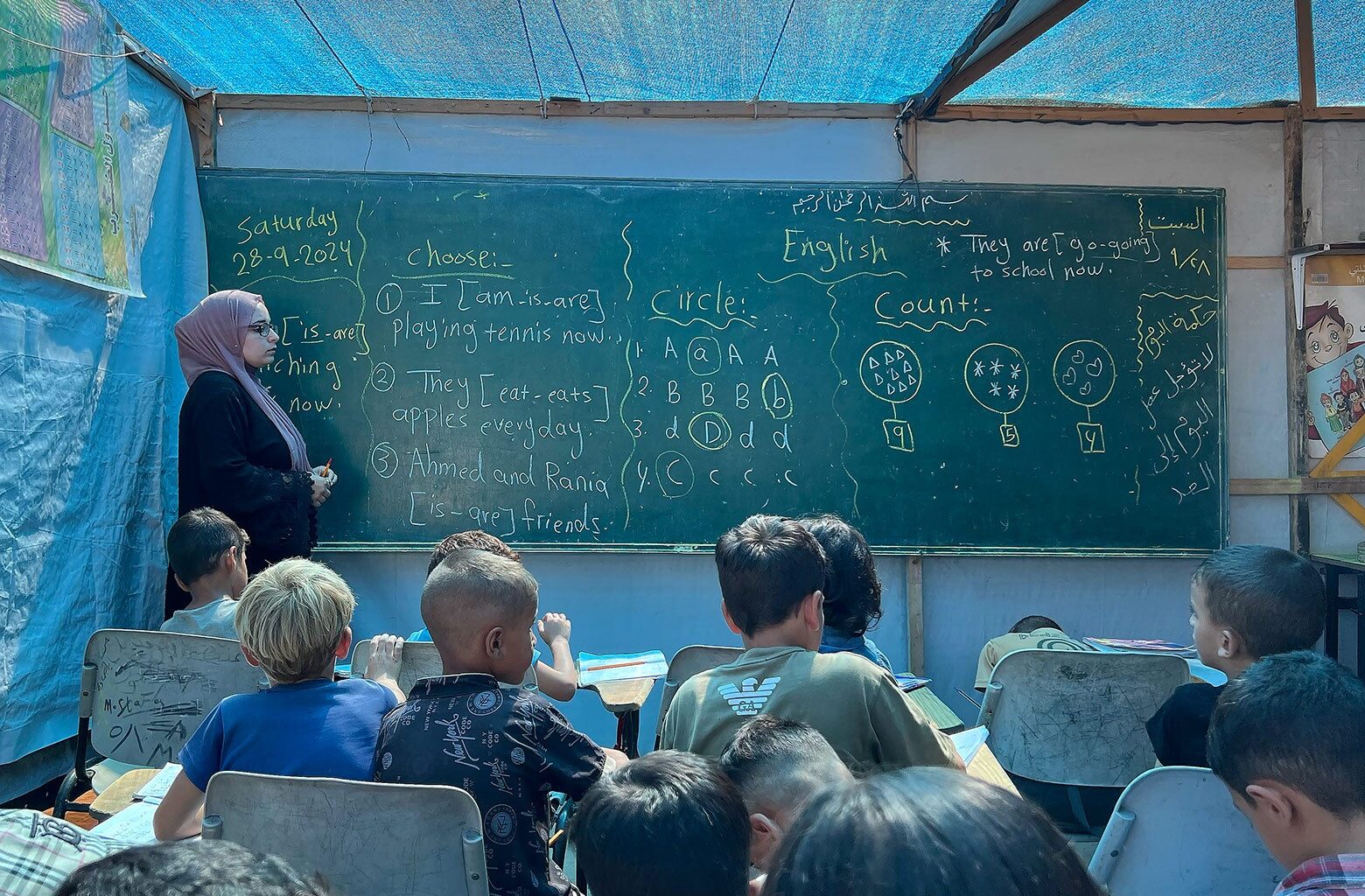

In the second year of the war though, parents’ resolve to keep their children learning has survived. Individual educational initiatives began to appear in various displacement camps; many set up a teaching tent for children in primary school to learn basic subjects including mathematics, English, and Arabic. The ongoing war makes any activity for children seem dangerous to their lives, because the bombing does not stop, and it targets such a wide variety of areas. But some students enjoy the lessons as a break in their daily routine in the tents. They are tired of waiting in lines for water, food, and bread. They want to feel like children who have the right to education. They go to the teaching tents, some of them barefoot (they no longer have shoes), their clothes worn out. They sit on the ground, as they do not have school desks, save for a lucky few. All that sitting in the wrong way and writing on the ground tires their backs.

Ruwaida Amer

I have often walked between the tents and seen these children. When I talk to them, they tell me that school has a different place in their hearts. Some of them said, “I miss waking up early. I want those days to come back.” “I would go with my classmates who waited for me in front of the house. We would take our lessons and wait for break time to play.” “I miss going home and having my mother wait for us to eat lunch together, review our lessons, and be safe and warm in our home.” Some of them are in the upper grades, not the first or second, and they do not benefit from the basic lessons that are the only ones available. They feel bored with the classes, believing that there is a lot of information that they are missing. There is no teaching for their more advanced academic level.

Ruwaida Amer

Despite Surviving War After War, I Used to Be Proud of My Home. But Now, Everything I Loved Is Gone.

Read More

I met a 10-year-old girl named Salma who is in the sixth grade and has been displaced from the north to one of the UNRWA schools here. She spoke with great dissatisfaction about the educational tents. She misses the science lessons that she loves. She knows how to read and write in Arabic and wants to learn higher skills, at the level of her studies. She worries that crowding children inside the small tents helps to spread epidemics. She also sees these spaces as unsuitable for both the summer, because they get very hot, and the winter, when they do not protect from the cold.

Salma says that she misses the security of her old life; her passion for education has become very low. She is afraid that the war will continue and that she will therefore lose many years of schooling. Salma wants to be a doctor in the future, and she is very afraid of being ignorant of science; “I do not know what our fault is [in all this], as children, that we should have to miss out. I want to go back to my school. I miss my teachers and my lessons. I do not want to stay in the tent without an education.”

Ruwaida Amer

The Ministry of Education in Ramallah has tried to save each school year by offering online teaching, but this has not been easy to access for tens of thousands of students in Gaza who live in tents without good internet connections. The possibility ultimately has become more of a burden on students. They search for the internet, desperate to follow lessons, take exams, and get results in order to pass their grade levels without needing to repeat them again. Parents feel so much fatigue. The lack of internet means that even when their children find a connection, they are often on their own, and the parents can’t follow along to know what the kids’ lessons are or where they are in their schooling.

I’m a Middle School Teacher in Gaza. I’m So Worried About What My Students Are Missing.

“We Want a Humane American President.” “I Hope That Trump Wins.”: What Five Palestinians in Gaza Think About the Election.

There’s a Threat to Our Lives in Gaza That’s Neither Bullets Nor Bombs

It Was a Controversial Program in Israel Before the War. Now It’s More Contentious Than Ever.

As a teacher, I cannot communicate with my students, wherever they may be in Gaza. I do not know where they are. I was able to reach a few of them who have been able to survive the war and travel to Egypt. But even these children are still suffering, far from Gaza. They talked to me a lot about their memories of school. They dream of returning to it even for one day. They feel that their childhood was stolen during the war. They asked me many times if the school was OK or not. I had to tell them the truth, which is that last December we learned that it was severely damaged, and a number of buildings were bombed, including the theater and the high school students’ building. The Israeli army also burned the library and bulldozed the schoolyard, which had a rest area, a soccer field, and a basketball court.

I have been teaching over the internet when I can. I try to help my students by explaining science lessons weekly to those in sixth, seventh, and eighth grades in particular, because they do not benefit much from the Ministry of Education program. As a teacher, I am very worried about the future of these students. All the initiatives and attempts to keep kids learning are not enough to save their education so long as the war is ongoing. The bombing and destruction machine is still working. We are still losing hundreds of children, who are also students. The war is destroying all health, education, religion, humanity, and the very Palestinian presence on their land. Many parents say that they live their lives for the future of their children. But there is so little hope for tomorrow. The war has destroyed that future.