The football analytics boom has been firmly established, but its role within the game remains debated.

Some argue that data has cleansed the game to such an extent that football has become too uniform for the average fan. For others, a data-led approach is romanticised as the tool that helps clubs find an edge in creating their underdog story.

Whatever your opinion, data analysis, paired with video technology, is becoming increasingly complex in football — even if its impact on a team’s tactical approach continues to be discussed.

The Athletic’s Michael Cox recently provided a compelling argument that the work being undertaken within football analytics might not have been applied as much on the pitch as we might have thought. While data-led recruitment — and even artificial intelligence — has become increasingly valuable for clubs, there are fewer examples of statistics directly informing decision-making within a game.

The question is, why might this disconnect exist?

GO DEEPER

Has the impact of analytics on modern football been overstated?

From a club perspective, the barriers can be more rudimentary than you might imagine.

Limiting factors can often sit outside the technological advancements that have been made. For example, the growth of in-game video analysis was stifled for nearly 10 years after pitchside video devices were banned in the mid-2000s — largely to protect referees from grievances over their performance — with rules not relaxed until 2018.

Coaches and managers had to wait until half-time to review any footage but pitchside devices are now commonplace, having a notable influence on tactical decision-making.

The use of video, in combination with data, has grown in popularity in recent years. For example, Catapult’s ‘MatchTracker’ combines player tracking data with real-time video to visualise what is occurring on the field and inform tactical decisions at the team or player level.

The rise of wearable technology in providing performance data can also provide a valuable source of information that can inform a manager’s tactical strategy as the game is being played.

“We can track distance between players and distance between the lines — so team length and width,” explains Daniel Shopov of Barin Sports, who develop GPS wearable devices for elite athletes.

“During a game, we measured how much the opposition was pressuring the team we were working with, as the defensive and midfield lines were getting closer together. That information dictated a substitution, so the coach ended up playing with a back five and allowing those lines to spread out. We were able to track this team shape in real time and then combine it with the physical condition to know which player to substitute.”

GO DEEPER

How the growth of wearable technology is transforming football

As simple as it may sound, investing in the correct infrastructure is another barrier that not every club has overcome when using data and video analysis. That can be as basic as having the devices needed to connect a network cable correctly within a stadium to capture live video and allow in-game event tagging (e.g. logging a shot-ending sequence, a counter-attack, or a set piece).

The recently built Tottenham Hotspur Stadium or Gtech Community Stadium is likely to be fully equipped with the latest technology, allowing analysts in the stand to use such methods to send tactical messages to the bench. With poorer stadium conditions, clubs lower down the football pyramid might not have the same luxury.

Edward Sulley has been working in performance analysis roles at City Football Group, Manchester City and Bolton Wanderers for over 20 years and has observed this technological evolution closely.

“We’re definitely starting to see more coaches using video and data in the way it should be intended to, to aid decision making,” said Sulley, who is now director of customer solutions at performance analysis software company Hudl.

“More live data is becoming available too, with a growing field of companies driving this advancement for real-time data to be used to guide coaches.”

For Sulley, removing those barriers to success is crucial to helping sports analysis progress further. Hudl recently acquired football analytics company StatsBomb, with the goal of combining high-quality video and data for real-time, in-game analysis.

GO DEEPER

Hudl to buy football analytics company StatsBomb

“StatsBomb data is near-live, so it filters through the tagged events within a minute or two of the events happening,” Sulley said.

“If you’re a coach or analyst, you want to be focused on the game plan that you’ve come up with on a matchday. Is our approach working? What strategic changes do I need to be aware of? You don’t want to be focused on tagging ‘pass, shot, cross’ if you can help it.

“Ideally you want to focus on the really impactful, game-plan-orientated stuff, but you need that level of granularity of live data to help you influence that.”

(Jonathan Moscrop/Getty Images)

A high turnover of staff, as is often the case in football management, can be a disruptive barrier to creating a coherent analytical structure, as the receptiveness to data and video analysis may change from one manager to the next.

The threat of being sacked can lead to short-term thinking which means that decisions are not always conducive to best practice in the long term. Such a lack of security within the industry can determine the progress of football analytics within a club, league, or across the sport.

“Coaches are changing all the time in many of the leagues that we work with — it is very performance-based,” said Sulley.

“That increases the instability within the league, and then the quality on the pitch gets impacted, which influences the league’s commercialisation, revenues and inclination to invest further — so it is all a knock-on effect of having this instability in the first place.”

GO DEEPER

How data departments have evolved and spread across English football clubs

Allowing staff members to flourish is an underestimated quality.

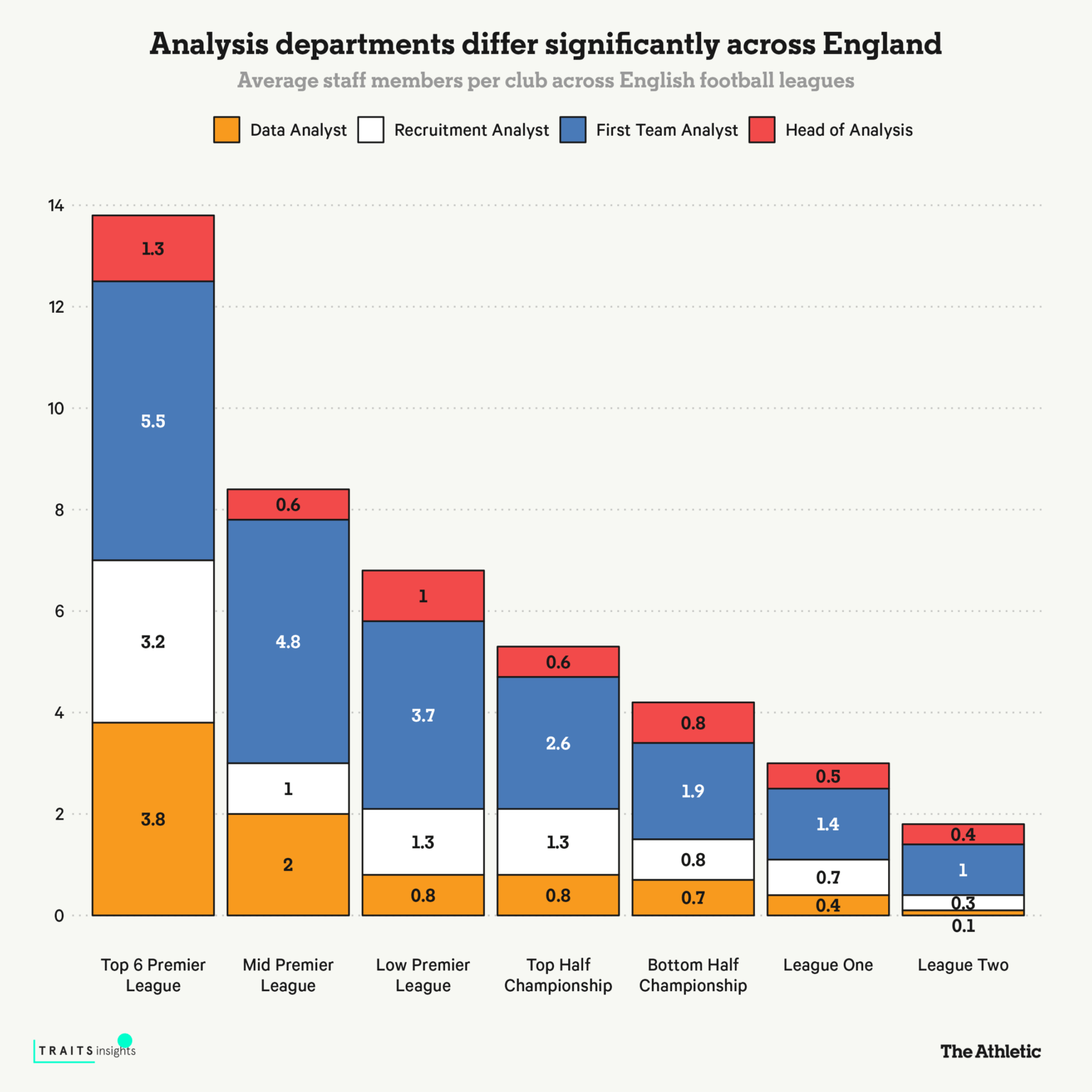

Having a single member of staff in a data role is barely going to scratch the surface within a club, with individuals often consigned to responding to ad-hoc requests from coaches. Instead, hiring a team of data scientists, data engineers and data analysts will provide a strong foundation to generate genuine, insightful impact in the long term.

As shown below in a recent analysis by Traits Insights, there is a notable decrease in the volume of analysis staff across English football leagues. Where a top-six Premier League club might average 13.8 members of staff across the whole analysis team, that falls significantly as you work down to the rest of the league and beyond.

It might sound boring, but streamlining workflows removes time constraints put on analysis staff and provides them with more time to share insight with key decision-makers such as coaches or sporting directors. That might be automation of post-match data reports, combining data from multiple sources into a coherent database, or developing data models that closely align with the club’s style of play.

Prioritising finances with a long-term view is key. The likes of Liverpool, Brentford, and Brighton & Hove Albion are often held as the gold standard in their data approach, but each club’s commitment to using such processes is the most important factor in their success.

“It costs money to build a good data infrastructure, but a lot of clubs don’t do it because it’s expensive — but is it expensive in context?” said Sulley. “If you’re not using data to influence the millions you’re spending on players, coaches, rehabilitation strategies, or injury prevention, then it is going to feel expensive.

“But if you have a plan and you’re using this data to turn a dial in your work, then it makes a lot of sense. If you’re spending £10million on a player, then a figure close to £300,000 is a relatively small amount of money in the bigger picture but it’s going to help you make smarter decisions.”

Brighton have been a shining example of this in recent years. A data-informed approach throughout the club has seen them buy players for low values and sell them for significantly more.

According to Transfermarkt, only Chelsea and Manchester City have generated a higher income in player sales than Brighton’s £393million since 2020-21 — with Moises Caicedo (bought for £4m, sold for £115m), Marc Cucurella (~16m to ~£60m) and Alexis Mac Allister (~£10.3m to ~£35m) being notable examples.

Having such investment from the hierarchy will maximise the chance that analytics projects will get seen, used and embedded within a club’s wider strategic planning. Greater opportunity to feed this information to a coach, manager, or sporting director is crucial.

“If you’re just processing data on the laptop all the time, you’ll have a really small amount of time to actually work on bigger projects that you know are going to move the dial,” said Sulley.

“A lot of people in that space will build these great statistical models but sometimes not have it seen by the right people, and it is so demoralising. It happens a lot in the industry and we are looking to change that for the better.”

Other sports such as the NFL are ahead of soccer in terms of real-time data analysis (Ric Tapia/Getty Images)

Removing barriers is one thing, but how might data shape a team’s tactics in the future?

With clubs reluctant to share ideas and give others a competitive advantage, progress might not be accelerated to the extent that many would like. Yet, the rise of artificial intelligence could play a pivotal role by analysing live video and data during games to deliver insights to coaches.

“A matchday setting is very highly pressured, so having time to process any tactical changes is where the best coaches stand out — they can make those assessments with their eye very quickly,” Sulley said.

“With this next generation of technology that can process data much more efficiently than humans, that is going to create a new wave of insights — which could suggest tactical changes to coaches in real time.”

It shows that the analytics journey is far from complete. Examples of data being used to directly impact a game may be limited, but the reasons why are simpler than they seem.

(Header design: Eamonn Dalton; photo: Getty Images)