Visitors to El Escorial will see treasures including a monastic patio, a royal ‘rotting room’ as well as paintings previously restricted to the gaze of kings and queens

IN MADRID – An imposing royal palace, a magnificent symbol of Spain’s Golden Age, is to get a facelift for the 21st century.

Almost five centuries after it was completed, visitors to San Lorenzo de El Escorial will discover new secrets about the treasures of this grandiose palace.

Built by Phillip II in the 16th century, during Spain’s Golden Age, El Escorial is testament to a time when Spain was one of the most important nations in the world (Photo: Silva Faci, Alejandro)

Built by Phillip II in the 16th century, during Spain’s Golden Age, El Escorial is testament to a time when Spain was one of the most important nations in the world (Photo: Silva Faci, Alejandro)

Tourists who make the 35-mile trip north-west of Madrid to the palace and monastery will now be granted access to a secret monastic patio and see paintings which until now have been restricted to the royal gaze alone.

Works by Titian, El Greco, Velázquez, Tintoretto, Zubarán and Juan Fernández de Navarette will be on show in the gallery, which closed seven years ago.

The two-year project, funded by €6.5m (£5.4m) from the European Union, aims to showcase this homage to Spain’s imperial might in a new light.

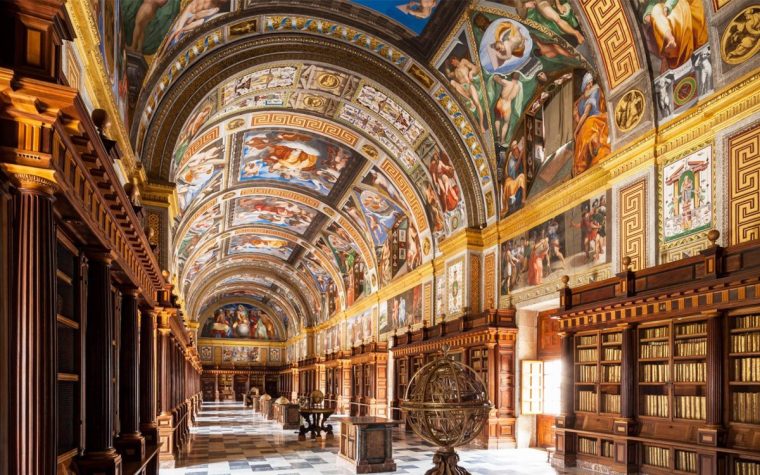

The library of El Escorial, the royal palace and monastery (Photo: Patrimonio Nacional)

The library of El Escorial, the royal palace and monastery (Photo: Patrimonio Nacional)

El Escorial, which Unesco included on its World Heritage list 40 years ago, already abounds with vast riches. Built by Phillip II in the 16th century, it is testament to a time when Spain was one of the most important nations in the world.

Apart from the artistic masterpieces on show, visitors with a taste for the morbid might delight in El Pudridero – literally The Rotting Room – where the remains of Spanish kings and queens putrefy in large caskets before being buried.

The largest Renaissance palace in the world, El Escorial is a monastery, basilica, royal palace, pantheon, library, museum, university, school and hospital in one, all spread across a 33,327 sq m site.

For the first time, visitors will be able to wander around the tranquil Patio of the Evangelists (Photo: El Escorial/Patrimonio Nacional)

For the first time, visitors will be able to wander around the tranquil Patio of the Evangelists (Photo: El Escorial/Patrimonio Nacional)

Spain’s military glories are celebrated in The Hall of Battles, a vast gallery filled with frescoes depicting the country’s military triumphs.

To see everything in the palace would take visitors hours – perhaps beyond the modern attention span – so the facelift aims to allow visitors to choose what appeals to them.

“To see everything, it would take the visitor a long time, up to about three hours,” Luis Pérez de Prada, head of buildings and environment at Spain’s national heritage institution, Patrimonio Nacional, told The i Paper. “We thought that a person could visit parts of the museum, but it does not have to be too long. They could visit the museum of architecture, for example, and return another time and see it with new eyes.

El Pudridero – The Rotting Room – where the remains of Spanish royals were left to putrefy before being buried (Photo: El Escorial/ Patrimonio Nacional)

El Pudridero – The Rotting Room – where the remains of Spanish royals were left to putrefy before being buried (Photo: El Escorial/ Patrimonio Nacional)

“We want these changes to allow people to evaluate what they would like to see when they enter El Escorial, which is a monument of great national importance. We also want to recuperate and open places which have been closed until now.”

El Escorial was built at the height of Spain’s Golden Age, a period from 1492 to 1659 during which Christopher Columbus journeyed to America, Miguel de Cervantes wrote Don Quixote and Spanish rule extended over much of Latin America.

Spain’s military glories are celebrated in The Hall of Battles, a vast gallery filled with frescoes depicting the country’s military triumphs (Photo: Silva Faci Alejandro)

Spain’s military glories are celebrated in The Hall of Battles, a vast gallery filled with frescoes depicting the country’s military triumphs (Photo: Silva Faci Alejandro)

When he started to build El Escorial, Philip II dreamt of building a monastery far from Madrid. His vision took 21 years to complete and involved two pioneering architects, Juan Bautista de Toledo, who had worked with Michelangelo, and later Juan de Herrera.

El Escorial is not exactly off the tourist track – it attracted more than 450,000 people last year – but authorities hope these changes will attract more visitors who often take bus trips from Madrid.

One change designed to give visitors an idea of the importance of El Escorial is that they can enter not from the side of the building but by the imposing Patio of Kings, a courtyard which allows people to appreciate the huge scale of the place.

For the first time, visitors can also wander around the Patio of the Evangelists, a tranquil garden of fountains and statues, while the painting and architecture galleries will also be reopened to the public. The facelift is due to be completed by 2026.

“People will be able to see new things and appreciate the importance of El Escorial,” Mr Pérez de Prada said.