The number of facilities studied was 79, with 43 health facilities for the intervention and 36 for the control cases. The breakdown by medical region shows 28 intervention facilities versus 23 control facilities in the Thiès medical region, and 15 interventions facilities versus 13 control facilities in the Kédougou medical region. Private health facilities are much more represented in the Thiès region than in the Kédougou region (p-value = 0.02). This could have an impact on the comparability of districts in the Thiès medical region compared with the Kédougou medical region, particularly with regard to directives concerning feedback obligations (from lower to higher levels and vice versa), the forwarding of certains types of information or the transmission of instructions.

Most facilities (from 70 to 93%) keep copies of RHIS reports. The proportion of facilities keeping copies of RHIS reports is not statistically different between control and intervention districts within each region (Kédougou RM, p-value = 1; Thiès RM, p-value = 0.336). The percentage between control and intervention districts in across regions (p-value = 0.386) (Table 1).

Structures kept on average between 9 and 11 different monthly or quarterly RHIS reports in 2017 concerning deliveries, prenatal consultation (CPN), vaccination and the global zone report. The collection tools are important in that they provide information on key indicators relating to the healthcare system. As one respondent in Kédougou put it: “Even if there are many tools, they are essential because they provide all the data on maternal, child and adolescent health, and they really enable us to work in good conditions”. Key informants also pointed out that some tools are heavy and bulky, while others are obsolete and unused. Some tools are also considered to be out of step with DHIS2 forms. This is the case for the gender data available in DHIS2, which is not collected at community level. This situation prompted the Kédougou service provider to say that “ the gender approach has been integrated everywhere, but when you look at the collection tools at the health hut level, they don’t integrate this change for the time being”.

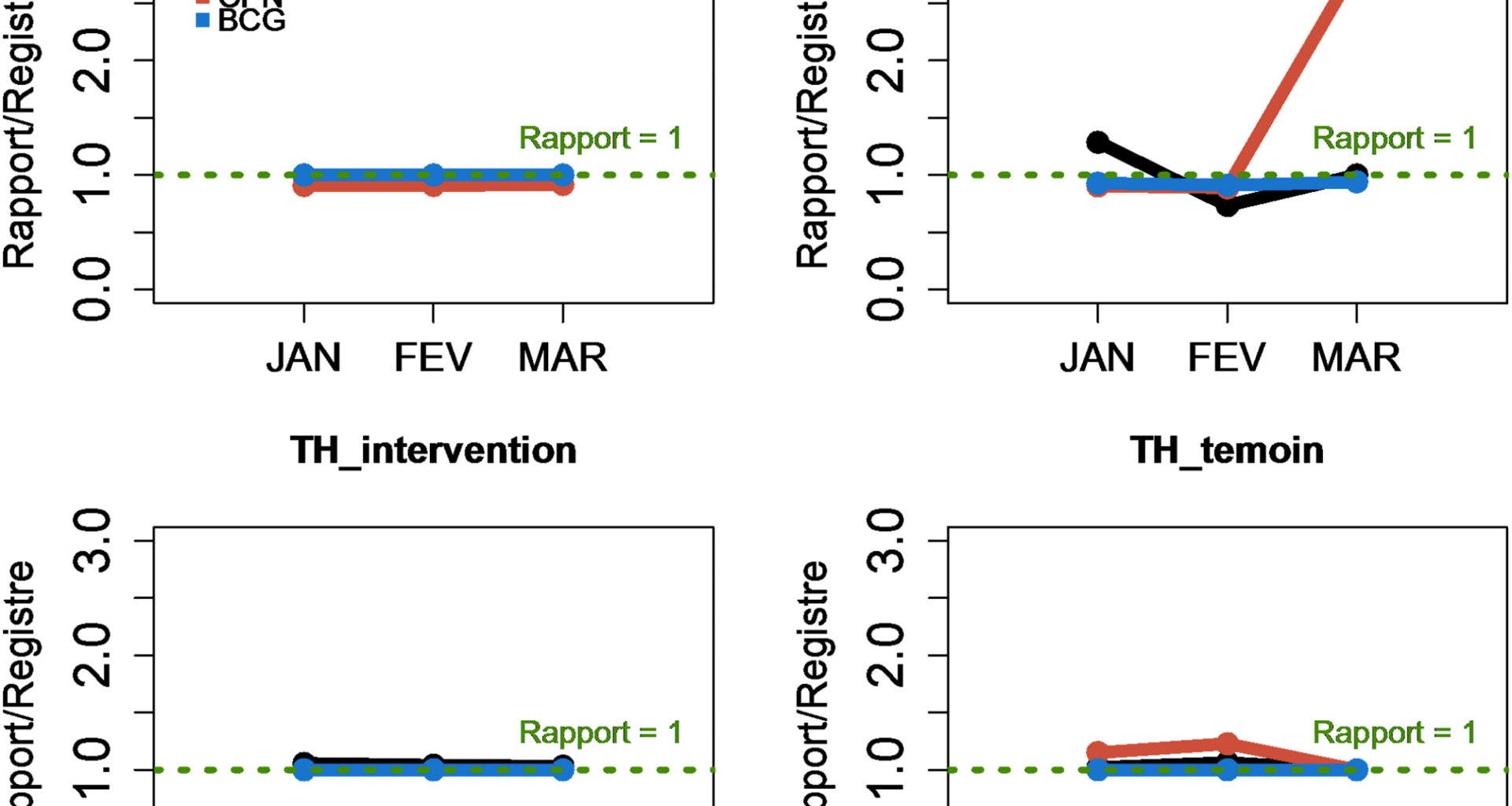

Based on the accuracy measurement, there were some discrepancies between the two control districts, particularly for the prenatal consultation act “CPN” in Saraya, concerning the number recorded in the registers and the reports from January to March 2018 (Fig. 1). However, in the intervention districts, the ratio was equal to 1.

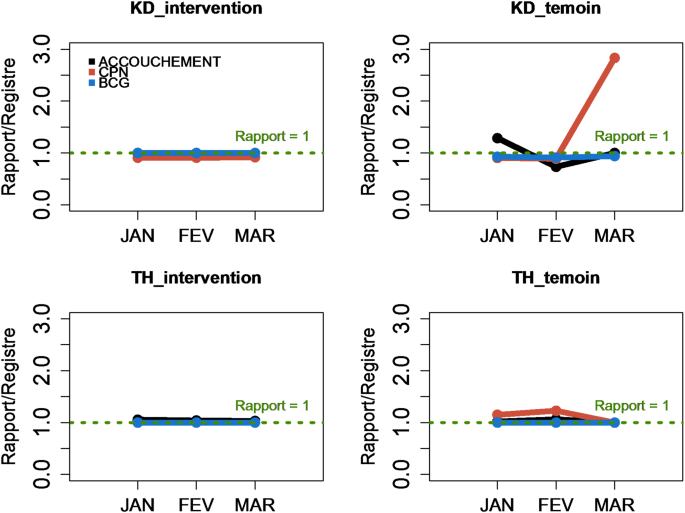

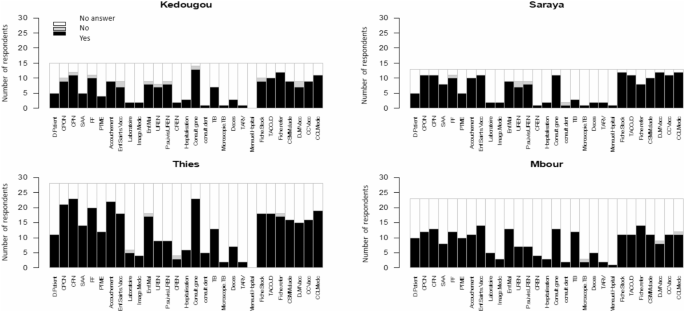

The degree of conformity between register figures and report figures is then assessed through directives from superiors concerning the verification of data accuracy. In this respect, we note a marked disparity in the transmission of directives between districts (inter- and intra-region), with 100% of Saraya health facilities receiving directives from the higher level for at least one of the items relating to data accuracy. This rate was only 14% for health facilities in Kédougou in Kédougou (Fig. 2). In addition to the directives received to improve compliance with data quality standards, it was also mentioned that quality control was carried out through supervision, coordination meetings and by the provider himself. Supervision covers both the global health information system and the use of the DHIS2 platform.

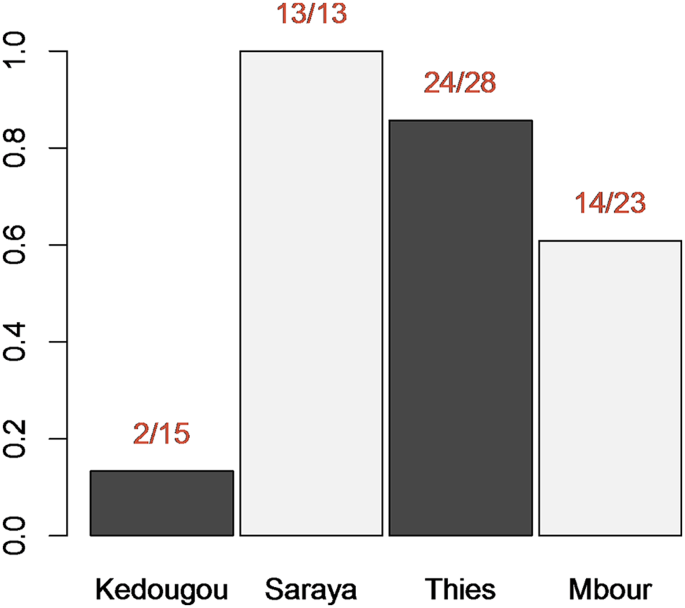

The existence of coercive sanctions varied from district to district, with rates ranging from 7% (KD) to 71% (TH). The proportion of health facilities receiving sanctions for non-compliance with directives was less than 80% (Fig. 3).

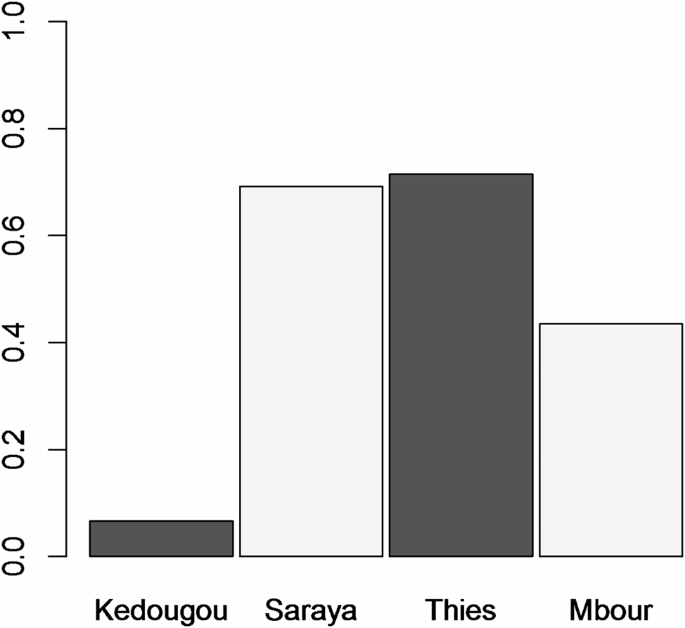

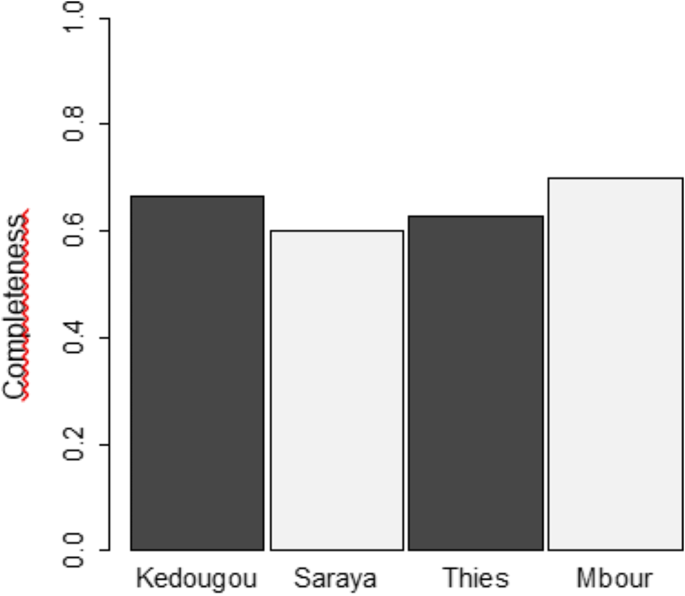

Overall, an average completeness level of 0.64 was observed across all regions (standard deviation = 0.44). Exhaustiveness was not significantly different between districts (Kédougou: 0.67, Saraya: 0.60, Thiès: 0.63, and Mbour: 0.70). Another aspect of data completeness is the presence of the same items in several registers managed by different service providers (Fig. 4).

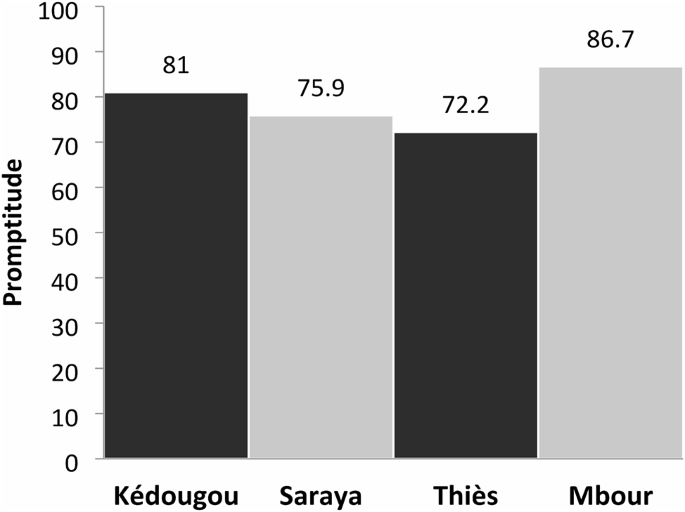

The study shows that the promptness rate from January to March 2018 was between 70% and 90% in the four health districts studied. The Mbour district has an 86.7% promptness rate, compared with 72.2% for the Thiès district, the Saraya district 75.9% against 81% for Kédougou (Fig. 5).

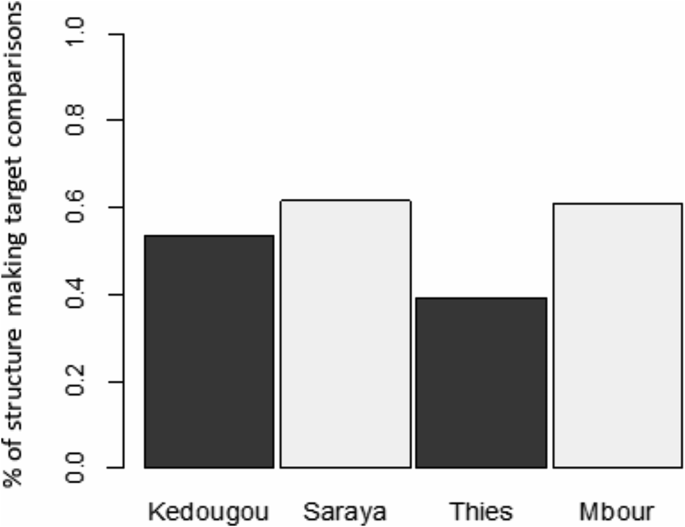

Concerning the data processing and analysis indicator, only 40–60% of facilities per district were self-evaluating. Intervention and control districts remained comparable for this indicator within each medical region and all medical regions combined (Thiès MR: p-value = 0.16; Kédougou MR: p-value = 0.72; all regions combined: p-value = 0.18) (Fig. 6).

Some operational-level providers report that they analyze the data collected through the DHIS2 to assess their performance by comparing their indicators with district, medical region and national level targets. However, it was pointed out that nurses are not equipped to carry out this task of data analysis and comparison of indicators optimally, an activity generally devolved to the district chief medical officer (MCD) and the regional chief medical officer (MCR). Nevertheless, data analysis and comparison were seen by many nurses as a means of self-assessment and preparation for planning.

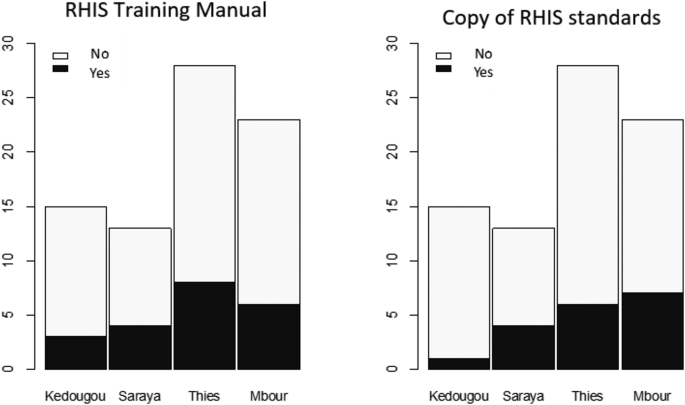

In most facilities visited in each district, healthcare staff does not demonstrate any knowledge (or application) of RHIS policies, standards, and protocols, especially those working for mutual health associations and private-sector providers. Most healthcare providers are familiar with the RPIA, which they summarize as a series of tasks such as collecting, transmitting, and analyzing health data. However, this knowledge of the RHIS differs according to the respondent’s functions, initial training, and perception of the purpose of the health information system (Fig. 7). Other provider in the healthcare system have a limited understanding of the RHIS. For most community workers, the RHIS boils down to transmitting the reports they prepare during their activities. Because of its compulsory nature and lack of motivation, some of them perceive the transmission of reports as a monopolization of the fruits of their labor and a feeling of not being valued.

Healthcare providers see the RHIS as an important, multi-purpose device for providing information on the status of indicators, identifying problems at the point of service delivery, and, finally, making decisions. From this point of view, providers see it not only as a decision-making tool but also as a means of attesting to the quality and effectiveness of work and the extent to which the objectives assigned to the facility have been achieved.

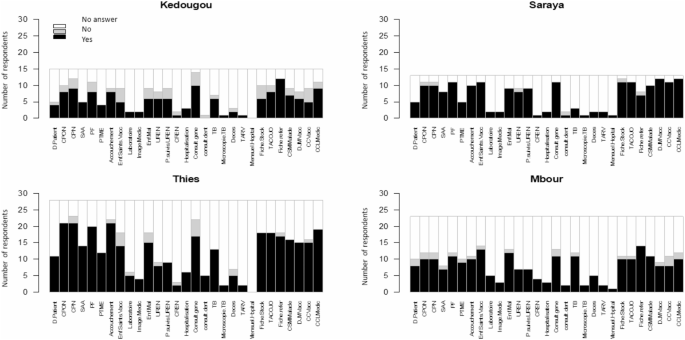

There is considerable variability in the ease of use of the thirty or so data collection tools currently used at health facilities. The ease of use of the tools is judged highly satisfactory by several providers across all districts, while others seem to maintain the opposite. In the Kédougou district, more than half the respondents mentioned the ease of use of data collection tools such as post-natal consultation (CPON), CPN, family planning (PF), childbirth, nutritional recovery and education units (UREN), TACOJO, and others. On the other hand, few respondents mentioned this facility for tools such as nutritional recovery and education centers (CREN). In the Saraya district, too, the situation is much the same.

In the Thiès districts, around 60% or more of respondents reported that tools such as ONC, ANC, FP, and childbirth were easy to use. In Mbour, however, more than half mentioned CPON, CPN, FP, and tuberculosis (TB) (Fig. 8).

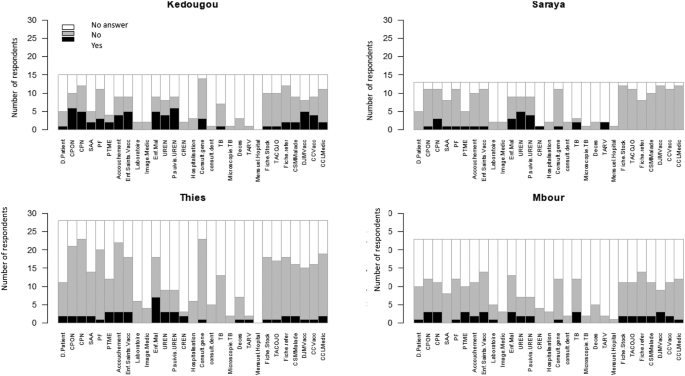

In Kédougou, at least half the respondents appreciated the recording space for tools such as CPN, CPON, PF, childbirth, general consultation, and TACOJO. However, in Saraya, this appreciation applies to SAA, vaccine follow-up, UREN, UREN follow-up, stock sheet, and the tools mentioned above. In Thiès and Mbour, the following tools were rated very low: laboratory, CREN, hospitalization, TB microscopy, death, and ARV treatment (Fig. 9).

Overall, the length of the forms was little or not appreciated by providers in the four (4) districts. And the percentage of non-response exceeded 50% for specific tools (Fig. 10).

Generally speaking, even if data collection tools are numerous, providers recognize that they enable all information on the health of mothers, children, and adolescents to be recorded under the right conditions.

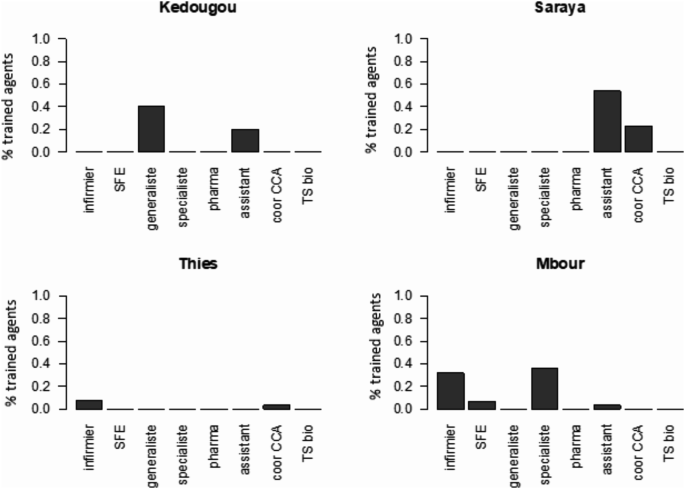

Provider training is another factor influencing the quality of RHIS data. In this respect, the study results show that healthcare staff receive very little or no training in entering information into the RHIS.

In Kédougou, 40% of general practitioners and 20% of assistants have been trained to enter RHIS data into the DHIS2. More than 50% of assistants and the coordinator have received training in Saraya. In Thiès, on the other hand, less than 10% of nurses and 5% of coordinators have received training. In Mbour, various providers (nurses, midwives, specialists, assistants, etc.) have received training. Overall, we note that pharmacists did not received training (Fig. 11).

Most providers deemed training insufficient, stating that capacity-building generally only concerns head nurses, meaning that untrained midwives are obliged to send their reports to the head nurses for entry into DHIS2. While midwives generally keep SMEA records, they are not generally trained to enter RHIS data into DHIS2.

Service providers also perceived the diversity of data production sources as a factor likely to influence the quality of maternal, child and adolescent health (SMEA) informations. It was observed that both private and public sector organizations produce data but that reports are not always systematically transmitted. In addition, discussions with service providers reveal a discontinuous interrelationship in managing the health information system. Indeed, even if private facilities operate in the same area of responsibility and are at the same level as, or lower than, the health post, the data they produce is not transmitted to the ICP.