Our study systematically examined GAI usage guidelines for scholarly publishing across medical journals, including author guidelines, reviewer guidelines, and references to external guidelines. The majority of top SJR ranked journals and the random sample of non-top SJR ranked journals provided GAI usage guidelines for authors and reviewers. This highlights medical journals’ proactive role in implementing GAI guidelines, likely due to their strong commitment to maintaining high standards in scholarly publishing [44]. The median of number of recommendations for author guidelines and reviewer guidelines were identical between the two groups of journals, indicating that once guidelines are adopted, the level of comprehensiveness tends to be largely similar. Despite this, these guidelines often lacked comprehensive coverage of all types of academic practices. The high proportion of both journal groups referred to external guidelines showed the critical role of these external standards in fostering ethical practices of GAI usage. Among the random sample of non-top SJR ranked journals, we also identified SJR scores that were associated with the coverage of different guidelines. Together, our results suggest that collaborative efforts are needed for explorations and improvements of GAI usage guidelines in scholarly publishing.

This study presents a timely, systematic, and in-depth evaluation of GAI usage guidelines across both the top and non-top SJR ranked medical journals. The relationships between journals characteristics and the coverage of such guidelines have been examined. Among non-top SJR ranked journals, a journal with a higher SJR score was more likely to provide GAI usage guidelines for both authors and reviewers. This finding is consistent with the previous study that showed a positive association between citation metrics and the inclusion of ethical topics in journal guidelines [44]. One possible reason may be that lower-ranked journals lack the resources or awareness to provide guidelines, which could lead to inconsistencies in GAI usage guidelines across different tiers of journals. This finding underscores the need for attention to journals with lower rankings.

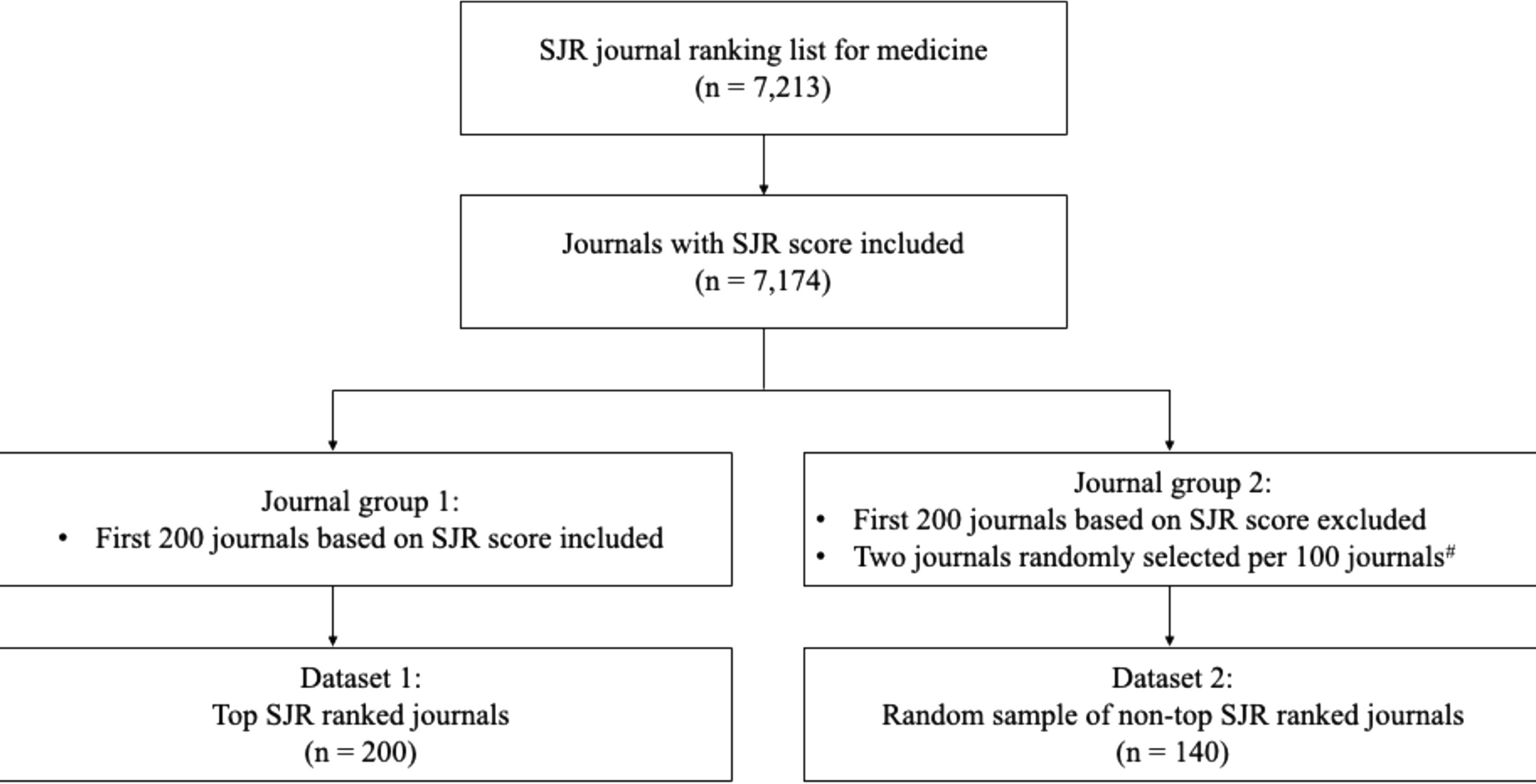

In comparison to a previous study [40], which reported that 86% of top journals provided author guidelines, our study found a similar proportion (80%) among top SJR ranked journals. Despite the high proportion of guideline coverage, top SJR ranked journals were more likely to provide author guidelines than non-top SJR ranked journals. This finding aligns with our expectations because of top SJR ranked journals’ initiative role in establishing standards on the use of emerging technologies such as GAI. These better coverages can be attributed to several factors. They include more accessible advanced AI technology, stringent regulatory environments, and robust scholarly communication networks [50,51,52].

We did not observe significant regional differences in GAI guideline coverage, possibly because the overall coverage of guidelines was relatively high across all regions. This observation contrasts with previous studies that have identified regional differences as a key factor in how research integrity topics are addressed in author guidelines [35]. One potential explanation is that GAI guidelines are being adopted more uniformly across regions due to the global nature of AI’s impact on scholarly publishing.

Both the top SJR ranked journals and non-top SJR ranked journals had a median of five recommendations for their author guidelines out of a seven. While some types of recommendations were provided for authors, there is still considerable room for enhancement. For example, both groups had lower percentages of journals providing recommendations for data analysis and interpretation and fact-checking. Data analysis and interpretation are fundamental to the reliability of research findings and fact-checking is essential to ensure the accuracy of the produced content. Lack of guidance in these critical areas may raise significant concerns such as inappropriate research conduct and the dissemination of false or biased information. A greater comprehensiveness can help authors adhere to ethical standards and prevent potential misconduct, including plagiarism or misrepresentation of AI-generated content as human work. Our findings showed that both top and non-top SJR ranked journals have room for improvement.

Across journals, consensus has been achieved for four of the seven recommendations examined in author guidelines, and disagreements were observed for three recommendations related to content generating applications. The remarkable capacities of GAI justify its usage in scholarly writing, especially for language editing [4, 53,54,55]. However, its risks threatening research integrity require authors to conduct fact-checking and usage documentation but not to grant such tools authorship [56]. These agreements show how the scientific community is embracing GAI in a cautious way. For example, the emphasis on fact-checking and usage documentation is necessary for preventing fabrication and potential biases and promoting transparency and trust [57].

Notably, journals differ in their instructions on where and how to disclose GAI usage. Some journals may not specify a particular location for the declaration or mention it generally as part of the submitted work. Others may provide more detailed guidance, specifying that GAI usage should be disclosed in the methods section, cover letter, or acknowledgment section. Additionally, while some journals require authors to report any use of GAI, other journals permit authors not to do so if such tools were solely used for language editing. This may be explained by journals’ different interpretations of GAI applications. Together with two other recent studies showing inconsistencies in what to disclose of GAI usage, a need is highlighted surrounding standardization of GAI usage disclosure and documentation [40, 41, 58]. More importantly, journals held different and even opposite stances for content-generating applications, including manuscript writing, data analysis and interpretation, and image generating. This is due to concern centered on plagiarism because it is challenging to trace and verify the originality of AI-generated content [59, 60].

As the first study that systematically examined GAI usage guidelines for reviewers, we observed disagreements on recommendations regarding usage permission across journals. We interpreted this disagreement as journals’ different stances on how to protect the confidentiality of manuscripts [8, 61]. Some journals specified conditions in which GAI can be used. For example, they required reviewers to obtain permission from authors and editors, to confirm that manuscripts shall not be uploaded as training data, and provide authors with the choice to opt for or against a GAI-assisted review process [30, 32].

Around 90% of top SJR ranked journals and 80% of the random sample of non-top SJR ranked journals have referred to external guidelines on GAI usage formulated by ICMJE, COPE, or WAWE. This underscores a collective endeavor to establish ethical benchmarks for GAI usage in scholarly publishing. Across the three external guidelines, all permitted authors and reviewers to use GAI. For the seven types of recommendations for authors, all guidelines addressed three items: prohibiting AI authorship, mandating usage documentation, and requiring fact-checking. While there are minimal variations among the guidelines, they are largely similar in their recommendations. Notably, language editing for authors and reviewers was not covered in any of the three external guidelines. It is possible that this omission arises from the perception that language editing, which is often managed by specialized services, is a well-established and safe practice, rendering explicit recommendations unnecessary [4, 55]. Another possibility is the perception that language editing poses fewer concerns related to misinformation and bias compared to content generation [56]. However, some organizations have adopted a stricter standard to promote transparency in GAI usage. For instance, the European Association of Science Editors (EASE) recommends that authors declare their use of AI for language editing in the Acknowledgements section or in a dedicated AI declaration section; In cases where this does not need to be declared, explicit recommendation should be provided to specify [62].

We observed overlaps and discrepancies between journal’s own guidelines and external guidelines. For author guidelines, we identified overlaps in usage permissions, with both journal’s own and external guidelines permitting GAI usage. Among the seven types of recommendations, our analysis revealed three areas of overlap: fact-checking, usage documentation, and authorship eligibility, where both journal’s own and external guidelines aligned whenever these aspects were mentioned.

However, language editing presented as one of the discrepancies. While many journals permitted its use for authors, external guidelines did not explicitly address this practice. Other discrepancies also included manuscript writing, data analysis and interpretation, and image generating. For example, different journals may have formulated opposing recommendations for these items in their guidelines. For reviewer guidelines, discrepancies between journal’s own and external guidelines were pronounced in terms of usage permission. While journal’s own guidelines showed opposing recommendations, all three external guidelines permitted GAI usage for reviewers. Additionally, some journals provided recommendations on language editing for peer review, which was not covered by external guidelines.

We identified three main aspects of GAI usage guidelines that need urgent improvements. First, while most medical journals provided their own GAI usage guidelines or referenced external guidelines, these guidelines often lacked comprehensive coverage of all types and deserved improvement. Details of the guidelines should be specified to avoid confusion, especially for content-generating applications. Our systematic evaluation of available GAI usage guidelines provides a roadmap to clarify expectations on proper GAI practices. Second, disagreements identified across guidelines warrant special attention. Although these disagreements highlight the continuously evolving use of GAI, it is possible to establish a framework of proper practices and specify recommendations under different scenarios. For example, journals may consider standardizing usage documentation by integrating questions into the manuscript submission system; ascertaining whether GAI was used, and if so, detailing specific purposes and ensuring accountability. Third, given the rapid evolution of GAI systems, scientific communities have recommended the adoption of “living” GAI usage guidelines. These guidelines will undergo continuous revision and adaptation either monthly or every three to six months [63]. Regular updates to author and reviewer guidelines are necessary to keep pace with evolving ethical standards, technological advancements, and best practices in scholarly publishing [33]. This dynamic approach ensures that guidelines remain relevant and effective in addressing the challenges posed by new AI developments.

Our study has several strengths. It pioneered a systematic and quantitative examination of GAI usage guidelines across top SJR ranked journals and a random sample of non-top SJR ranked journals, which provides an overview of the current regulations in scholarly publishing. It also synthesized existing GAI usage guidelines for both authors and reviewers and established a systematic checklist. We further provided recommendations aimed at improving existing GAI usage guidelines for scholarly publishing and promoting the proper use of GAI tools. While our study focused on medical journals, we encourage broadening the scope of this type of research to include other disciplines. This will provide a more comprehensive understanding of the scholarly publishing landscape across various fields and help identify discipline-specific challenges and best practices. Such expanded research efforts would contribute to the development of more nuanced and effective guidelines that address the diverse needs of the academic community.

Our study also has limitations. First, we only focused on publicly available information for reviewer guidelines due to the availability of related data. This is because reviewer guidelines in some journals may be accessible only through submission systems or via invitation emails. Incorporating such information in future research may give a more complete overview of GAI usage for reviewers. Similarly, for usage documentation, our analysis was based solely on publicly available information from the journal or publisher’s official website. Future research could gain deeper insights by conducting an in-depth review of submission systems to capture a more comprehensive understanding of GAI usage documentation. Second, the checklist of recommendations we identified and used to calculate the number of recommendations may not reflect equal importance. As GAI tools continue to develop rapidly, the relative significance of individual recommendations may also shift over time. While our checklist was designed to offer a foundational overview of GAI usage guidelines, it is important to interpret the number of recommendations with caution. Additionally, as a cross-sectional study, our data was retrieved from a predefined list of journals on a specific 7-day period. Future studies can access the historical records of the guidelines to provide insights about how these guidelines are developed and adapted over time. Third, while we used SJR score as the primary metric for journal selection, we acknowledge the importance of incorporating other metrics, such as impact factor, to provide a more comprehensive analysis. Future studies may explore different journal ranking metrics to further validate and expand on our findings.