CP PHOTO: Mars Johnson

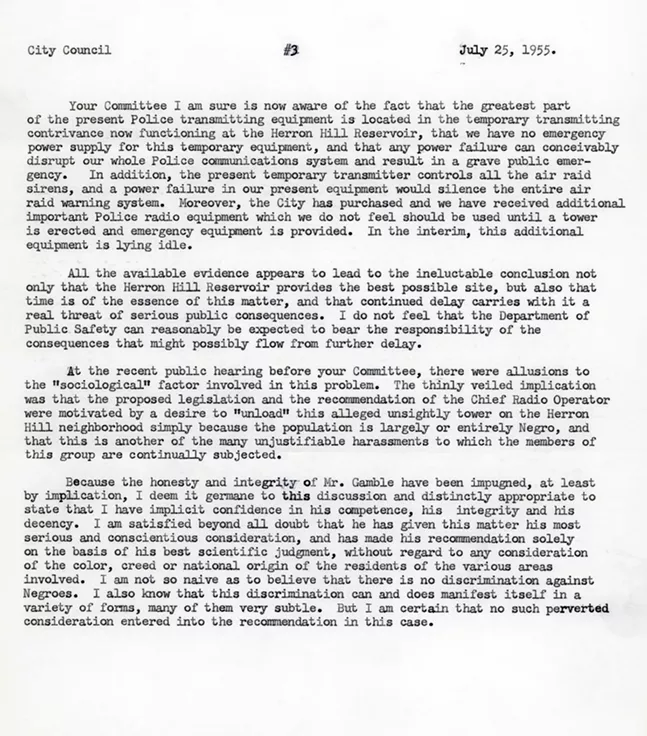

The radio tower on the Herron Hill Reservoir in the Sugar Top neighborhood of Pittsburgh

Sugar Top is the name that Black Pittsburghers gave to the highest elevation in the Upper Hill District neighborhood. Its bungalows, four-squares, and period revival homes were an attractive destination for the city’s upwardly mobile Black middle class in the first half of the 20th century. Moving to Sugar Top from the Lower Hill District became a badge of honor. Sugar Top residents protected their neighborhood from encroachment by urban renewal and land uses they believed would degrade their community.

Between 1952 and 1955, homeowners there mounted two campaigns to block the construction of new radio towers in their neighborhood. The battles became forgotten early episodes in a city with a long history of environmental activism. They were among a small number of 20th-century episodes involving Black residents resisting what they perceived to be environmental injustices.

CP PHOTO: Mars Johnson

Sugar Top neighborhood of Pittsburgh

A suburb in the city

“The richer more affluent African Americans [lived in] Sugar Top,” folklorist Hugo Freund wrote of the Hill District history in 1992. “In Sugar Top, the houses are larger, manicured and perhaps designed by architects.”

“Sugar Top was a hub within the Hill, but I looked at those people as the elite,” explains barbershop owner Michelle Slater, who grew up in the Hill District. “They were just a little bit, to me, higher class than just basic Hill people.” Slater’s grandmother once lived in Sugar Top with her common law husband, George Harris. George was the brother of racketeer William “Woogie” Harris and photographer Charles “Teenie” Harris.

PHOTO: Courtesy Pittsburgh City Photographer Collection via historicpittsburgh.org

Herron Hill Reservoir and the police radio tower built in 1955

CP PHOTO: Mars Johnson

The radio tower on the Herron Hill Reservoir in the Sugar Top neighborhood of Pittsburgh

It was home to Black lawyers, journalists, business owners, racketeers, athletes, and church leaders. So many pastors lived on the six-block Anaheim Street that it became known as “Preacher’s Row.”

Built in 1880, the Herron Hill Reservoir occupies the second-greatest elevation in Pittsburgh and is one of the highest points in Allegheny County. “The outlook from the summit is grand, and the Hill is worthy of a visit,” wrote Pittsburgh guidebook author George Thornton Fleming in 1916.

More than a century later, the panoramic view is still spectacular. The reservoir dominates a city park in the heart of Sugar Top originally named Herron Hill Park. The city changed the park’s name in 1984 to Robert E. Williams Memorial Park, honoring the city’s first Black magistrate.

By the 1950s, the Upper Hill had become established as the city’s premier destination for Black homeowners. But to city leaders, it was still a Black neighborhood that was fair game for urban renewal. As demolition ramped up in the Lower Hill, Upper Hill residents successfully mobilized to prevent the city from fulfilling urban renewal plans that included leveling 900 acres.

“Despite the devastation in the Lower Hill District and Middle Hill District, property values in Sugar Top have not declined,” Freund wrote 40 years later. “Herron Hill and Sugar Top are very different from the stereotyped portraits of ghetto life that so often describes the Hill District.”

The tower wars come to Sugar Top

After World War II, radio and television towers sprouted in communities across the country. Broadcasters, telephone companies, and the Western Union Telegraph Company bought and rented land to build out new infrastructure.

PHOTO: Courtesy Pittsburgh City Photographer Collection via historicpittsburgh.org

Herron Hill Reservoir and the police radio tower built in 1955

PHOTO: Courtesy City of Pittsburgh Archives

Page from a July 25, 1955, letter from Pittsburgh Public Safety Director David Olbum to the Pittsburgh City Council denying charges that the police radio tower was being built in Sugar Top because its residents were Black

Wartime advances in radio technology included microwaves for sending telegrams, long-distance telephone calls and faxes. The Federal Communications Commission also began licensing television stations. Earlier technologies, like the use of radios in police cars, required towers. Broadcasters, telecommunications companies, and local governments saw Herron Hill and Spring Hill on the North Side as prime tower sites.

Some communities pushed back against proposed new towers. Opponents testified before zoning boards and lobbied elected officials to prevent what many described as visual blight from encroaching on their neighborhoods. In Washington, D.C., residents of the Tenleytown neighborhood successfully forced Western Union to disguise a new microwave terminal as a silo-shaped building with concealed antennas; the company had scrapped an earlier design to camouflage it as a clock tower.

In 1947, KDKA had built a 500-foot tower below Sugar Top near the University of Pittsburgh sports complex. It was far enough away from Sugar Top that there were no reported complaints ahead of its construction. WQED bought the tower in 1953 and replaced it with a 593-foot tower that’s still visible from many parts of the city.

CP PHOTO: Mars Johnson

The radio tower on the Herron Hill Reservoir in the Sugar Top neighborhood of Pittsburgh

CP PHOTO: Mars Johnson

The radio tower on the Herron Hill Reservoir in the Sugar Top neighborhood of Pittsburgh

Other towers built inside the city after World War II included a Western Union microwave relay station in Northview Heights, completed in 1946, and television towers in Forest Hills, the West End and South Side.

The tower wars arrived in Pittsburgh in 1951 when a contractor for the then-CBS affiliate WJS proposed building a 600-foot tower on Camp Street across from the Herron Hill Reservoir. The Pittsburgh Radio Supply House, Inc., approached city leaders requesting a zoning change to build the tower on Camp Street. Residents from Sugar Top, led by Black attorney and future councilmember Paul F. Jones, successfully defeated the effort, which would have included rezoning part of Sugar Top from “Residential” to “Slope.”

After failing to get the necessary approval, the Pittsburgh Radio Supply House company sold its lots to a construction company, which built two homes there in 1955.

Another scrap over towers broke out in 1955 when the city proposed building a new police radio tower next to the reservoir. Herron Hill residents complained to city leaders that existing infrastructure was making their neighborhood “look like an Oklahoma oilfield.”

Many of the complaints aired in the February 1955 hearing turned on what were described as “sociological factors.” Public Safety Director David Olbum wrote a letter to the City Council in July summarizing the complaints and factors in favor of building the new tower. He vigorously denied that the location was selected because of its proximity to Black-owned homes. Olbum wrote that there was no attempt to “unload this alleged unsightly tower on the Herron Hill neighborhood simply because the population is largely or entirely Negro.”

After hearing the complaints, Councilmember and Sugar Top resident Jones temporarily killed the measure. It was revived a few months later after Jones announced that the opposition had been withdrawn. The 75-foot steel tower built in 1955 is still there today.

A forgotten history

The Sugar Top towers were not isolated cases of local Black environmental activism. In 1965, Lincoln Park residents successfully forced Penn Hills to clean up sewage spills and dumping from East Liberty urban renewal activities in their neighborhood. Longtime Lincoln Park residents also recall that Helen Greenlee, wife of Pittsburgh Crawfords owner Gus Greenlee, bought two lots on her street to block the construction of new broadcast towers there.

Historians who have documented Black life in Pittsburgh acknowledge that environmental activism is a blind spot in their research. “The scholarship is sparse on this subject,” Carnegie Mellon University professor Joe Trotter emailed Pittsburgh City Paper in response to questions about environmental history and Black activism.

Trotter’s University of Pittsburgh colleague Larry Glasco agrees. “A most important topic but understudied,” Glasco emailed City Paper. “I don’t know of an organized environmental movement, but searching the Courier under topic headings like trash, garbage, rodents and the like would turn up a lot of articles of Black residents complaining about unsanitary conditions.”

CP PHOTO: Mars Johnson

The radio tower on the Herron Hill Reservoir in the Sugar Top neighborhood of Pittsburgh

Pittsburgh Courier columnist Ethel Payne suggested that one reason Black residents bypassed environmental justice issues until the 1970s was that they were used to environmental racism. “Black folks used to laugh at white folks obsession with environmental protection,” Payne wrote in 1977. “Air pollution wasn’t no big thing with us. We’d been breathing bad ghetto air all our lives.”

The Sugar Top tower cases are a reminder that Pittsburgh has a long history of Black environmental activism. Some 21st century Pittsburgh residents might call those earlier efforts NIMBYism. Yet, they helped to protect and preserve an important part of Pittsburgh’s history.