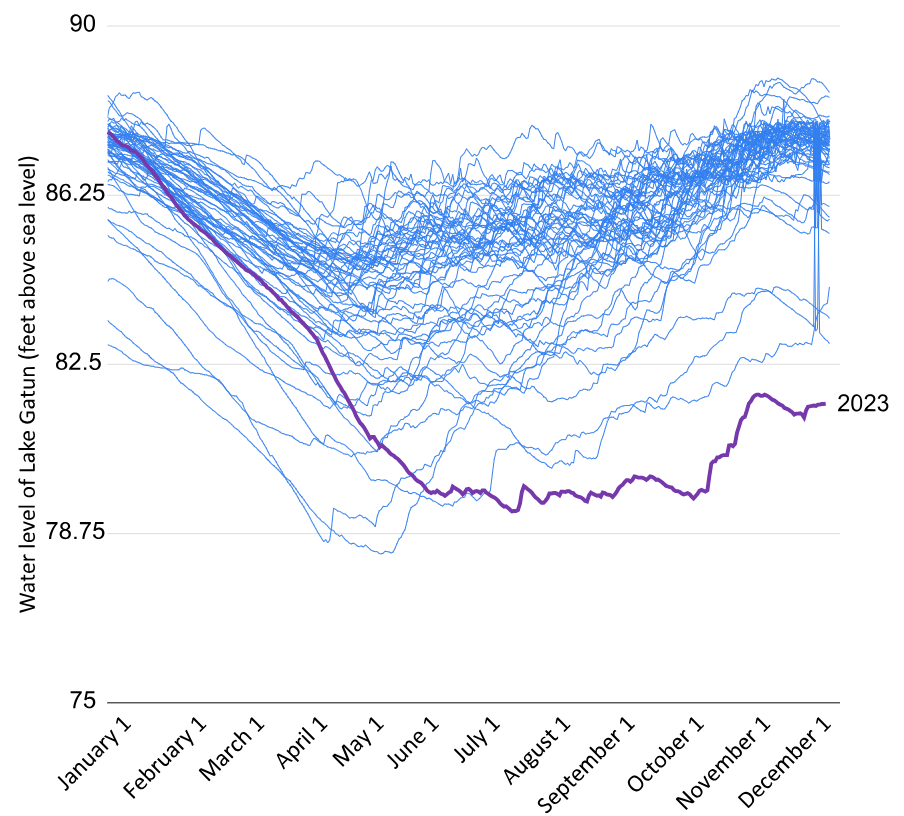

Water levels in the Panama Canal have been sitting low since May

2023, which has caused shipping delays and record-setting transit

fees. But is this protracted dry spell just bad luck or a sign of

things to come?

More than 500 hundred million tons of cargo.1 Over

14,000 transits. Roughly 4.7% of all goods transported by sea

worldwide.2 For more than a century, the Panama Canal

has served as an essential conduit in global transportation routes.

And following the completion of the Third Set of Locks Project in

2016, the canal is now able to accommodate larger ships with double

the cargo capacity of its original maximum.3 Despite

that expansion, for most of 2023 vessels seeking to enter the canal

have been confronted by lengthy queues, extended wait times and

extra fees imposed by the Panama Canal Authority. In August, when

the traffic jam was at its worst, 154 commercial vessels were

waiting for weeks to cross the isthmus.4

The root cause of these difficulties is too little water. The

Suez Canal in Egypt is built at sea level, and ocean water flows

through it freely, but in Panama, the canal is elevated and sealed

by locks at both the Pacific and Atlantic entries. Its operations

depend on freshwater from the Chagres River in central Panama,

which is dammed twice to produce the Gatún and Alajuela

reservoirs. Every time a ship crosses the canal, more than 50

million gallons of water are diverted into the locks and then,

after the vessel has been lifted, flushed into the ocean. In most

years, there is enough runoff to operate the canal and provide

water for hydroelectric power and human consumption. But in 2023,

Lake Gatún did not recover from its usual early year

drawdown5 and instead has remained low for the past

several months (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Water level in Panama’s Lake Gatún for 2023

compared with previous years.

Data source: Panama Canal Authority. Last updated: October 29,

2023

In response to the freshwater shortage, the Panama Canal

Authority has reduced the number of daily crossings by 10%, knocked

back the number of advance reservations and required ships to carry

less cargo.6

Shipping companies have also proved willing to pay record

amounts to skip the line. Avance Gas Holding Ltd. paid US $2.4

million (on top of the standard transit fee of US $400,000) to

secure faster transit for a liquefied petroleum gas

carrier.7 But why has Panama — wet, tropical

Panama — been so dry for so long in 2023? Is this recent

episode simply due to a string of bad luck or is it a harbinger of

future water problems spawned by climate change?

Not the intensity but rather the duration

Panama is a water-rich country because, for most of the year, it

sits under the Intertropical Convergence Zone (ITCZ), where the

trade winds collide and create an unbroken girdle of rainstorms

that circles the equator.8 When the ITCZ migrates

southward, Panama does experience a brief three-month dry season.

The rest of the time, rainfall is consistently high and often

intense. The two provinces that border the canal (Panama and Panama

Oueste) usually get more than 2 meters of rain each

year.9

Coming into 2023, the canal enjoyed quite a good position for

its overall water storage. As recently as July and August 2022,

Lake Gatún had actually never been higher for that time of

year. But once the calendar flipped, the lake fell lower and lower

through the first half 2023 and finally bottomed out in early June.

The lake has been even lower in the recent past; at no point did it

come close to threatening the record minimum of 78.3 feet, which

happened on May 19, 2016. But what makes this current drawdown

stand out is its duration. As of November 2, 2023, Lake

Gatún has remained low for nearly five months (Figure 1).

That’s never happened before in the history of the canal.

Unseasonably dry weather in Panama is often blamed on El

Niño. But the 2023 Panamanian drought started several months

before the current El Niño began. And although El

Niño events are usually associated with drier conditions on

the western coast of Central America, the tropical Pacific is not

the only factor that influences the region’s

climate.10 So we should be careful not to attribute

events like the current drought to a single, clear-cut cause.

Rainfall trends are hazy, but a hotter future is certain

Over the past few decades, Panama, like most of Central America,

has gotten warmer. This trend is mainly due to increasing nighttime

temperatures. Compared with the early 1970s, the region now

experiences fewer cool nights.10 For rainfall, the

geographic pattern of change is less consistent. Nicaragua,

Honduras and (southern) Costa Rica have gotten drier while

Guatemala has become wetter. But in Panama, rainfall does not show

a clear increasing or decreasing trend; however, we also should not

place too much faith in that conclusion. The most up-to-date

regional assessment of climate trends across Central America draws

upon very few weather stations from Panama. And none of those

stations are located inside the canal’s watershed.

For the immediate future, the situation in the canal may get

worse before it gets better. If the developing El Niño does

have its usual effect, Panama would be confronted by an extended

dry season and hotter-than-average temperatures into 2024.

According to the Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute, that

combination could lead to record or near-record low water levels at

Lake Gatún by March or April 2024.

If we look farther ahead, there’s more cause for concern.

Dr. Hugo Hidalgo at the University of Costa Rica is one of the top

climate scientists in Central America. He has argued that, although

climate models struggle to reproduce regional precipitation

patterns correctly, those tools all show that the region faces a

hotter future.10 A warmer atmosphere would mean greater

evaporation and more water lost from the Gatún and Alajuela

reservoirs. Because global warming may also push the ITCZ

southward, away from Panama,11 in the years to come it

may be even more difficult for the canal to secure an adequate and

reliable water supply.

The canal is and will remain ‘climate dependent’

In his 1963 speech inaugurating the Greers Ferry Dam in

Arkansas, U.S. President John F. Kennedy said, “A rising tide

lifts all boats,” arguing that economic development in one

state benefited the entire country.12 Because the canal

is a critical bottleneck in the global network of maritime trade,

when rainfall is abundant, carriers, producers, consumers and

Panama itself reap the benefits. Instead, the current drought has

presented the canal with its most significant challenge since its

opening in 1914.

In October 2023, administrator Ricaurte Vásquez Morales

commented that, when the new locks for the expanded canal opened in

2016, it would have been unthinkable to even consider working at

the water levels experienced in 2023.13 Only seven years

later, the Panama Canal Authority now is making plans to build more

dams to supplement Lake Gatún with extra water from

neighboring watersheds. But even if those plans bear fruit, it

seems certain the canal will always be vulnerable to drought risk

— and be the canary in the climate coal mine for Central

America.

Footnotes

1 Panama Canal Authority. Panama Canal traffic by fiscal

years. (2022).

2 United Nations Conference on Trade and Development.

Review of maritime transport. (2022).

3 The Waterways Journal Weekly. Panama Canal Authority

celebrates fifth anniversary of Neopanamax Locks, July 11, 2021.

(2021).

4 CNBC. ‘This is going to get worse before it gets

better’: Panama Canal pileup due to drought reaches 154

vessels, August 9, 2023. (2023).

5 Reuters. Focus: Historic drought, hot seas slow Panama

Canal shipping, August 21, 2023. (2023).

6 Panama Canal Authority. Panama Canal prepares for the

impact of climate events, June 6, 2023. (2023)

7 Bloomberg. One ship in Panama Canal paid $2.4 million

to skip the line, August 31, 2023. (2023).

8 Lindsey, R. & Kennedy, R. Annual migration of

tropical rain belt. Climate.gov, 2011. (2011).

9 World Bank. Panama. Climate Change Knowledge Portal.

(2023)

10 Hidalgo, H. Climate variability and change in Central

America: What does it mean for water managers? Frontiers in Water

2, Article 632739. (2021).

11 Mamalakis, A. et al. Zonally contrasting shifts of the

tropical rain belt in response to climate change. Nature Climate

Change 11, 143-151. (2021).

12 Kennedy, J.F. Remarks in Heber Springs, Arkansas, at

the Dedication of Greers Ferry Dam. The American Presidency

Project. (1963).

13 Seatrade Maritime News. The Panama Canal is

‘climate dependent’. (2023).

The content of this article is intended to provide a general

guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought

about your specific circumstances.