Since 2020, Denmark has separately classified people from or with heritage in primarily Muslim countries and regions in official statistics related to topics such as crime and employment.

Under that system, the Ministry of Immigration and Integration distinguishes immigrants and their children from the so-called ‘Menapt’ group, meaning people from the Middle East, North Africa, Pakistan and Turkey.

The term ‘Menapt’ has since come into frequent usage in political discourse, particularly with regard to immigration and not least citizenship.

The far-right party Nye Borgerlige said in 2021 it wanted people from these countries to be treated differently – meaning, more easily rejected – when applying for citizenship.

That scheme did not go anywhere, but changes to citizenship laws made the same year introduced “Danish values” questions to the citizenship test.

“And if you don’t want to go over that bridge – which consists of things like the Constitution taking precedence over the Quran, and women being able to choose their own partners – then Denmark isn’t the place to make your home country,” then-Liberal party spokesperson for citizenship, Morten Dahlin said at the time.

Advertisement

In 2025, the government is considering screening the personal views of prospective citizens as part of the application process

Recent data on new citizenships granted to people from English-speaking countries show that there has been no significant decline in the number of citizenships approved since 2021, when the most recent law change took effect.

For one country, the UK, there has been an increase in its citizens becoming naturalised Danes. This trend is likely to be linked to Brexit, because Denmark offers those people the chance to retain EU citizenship.

Do the data reveal any discernable difference for ‘Menapt’ countries with regard to Danish naturalisations?

IN NUMBERS: Is Denmark granting more or fewer citizenships to English speakers?

Advertisement

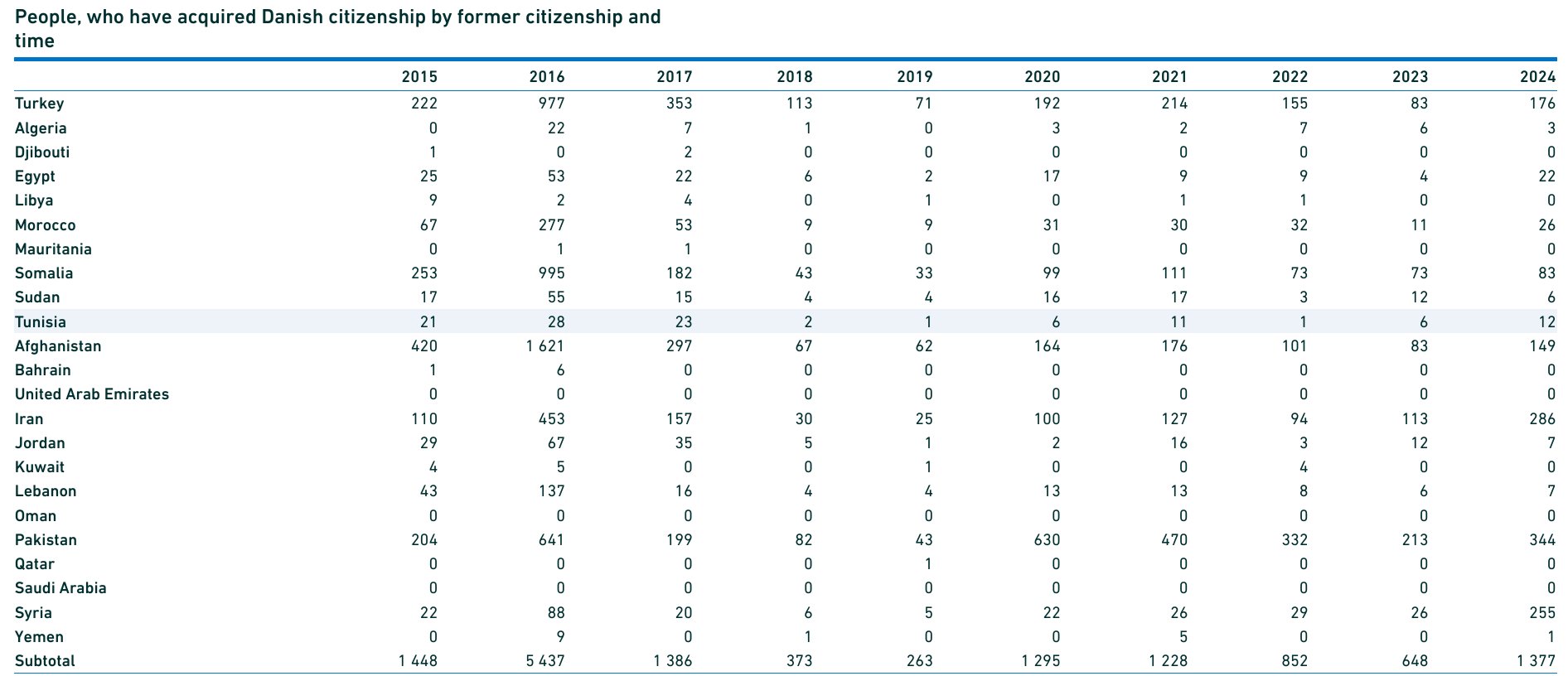

The designation ‘Menapt’ covers 24 different countries: Syria, Kuwait, Libya, Saudi Arabia, Lebanon, Somalia, Iraq, Qatar, Sudan, Bahrain, Djibouti, Jordan, Algeria, United Arab Emirates, Tunisia, Egypt, Morocco, Iran, Yemen, Mauritania, Oman, Afghanistan, Pakistan and Turkey.

The chart below shows the number of new citizenships per year for people from each of these countries, with the graph below displaying the total numbers each year.

Graph: Statistics Denmark

With the exception of an abnormally high number in 2016, there does not appear to be a noticeable decline over time, either since 2015 or since 2021, when the new citizenship rules took effect.

Here we can see the same pattern, whereby 2016 is an outlier. There is also a lower number from 2020-2024 compared to the preceding five years.

Speculatively, this could be linked to stricter citizenship rules — but it’s also worth keeping in mind that 2016 approximately corresponds to the amount of time people who fled to Denmark from Afghanistan in the 2000s would have has to wait before becoming eligible for citizenship (nine years is the general requirement).

For Pakistan, we see a different-looking graph with a peak in 2020 as well as 2016. The numbers remain higher after 2020. As we found in an earlier article on this data, Pakistan and the UK are the two countries to have provided the highest number of new Danish citizens over the last five years.

There is a different pattern again for people from Syria. While 2016 remains a peak year, the highest number of Syrians becoming naturalised as Danes was highest in 2024 by a fair margin. It’s worth noting that the Syrian civil war began in 2011 and large numbers of refugees arrived in Denmark from Syria in 2015, but also during the preceding part of the 2010s.

While it’s not possible to draw any firm conclusions from this analysis, it is difficult to argue that the stricter rules brought in in 2021 have reduced the number of citizenships awarded. It appears likely that a country’s individual circumstances affect fluctuations between years.