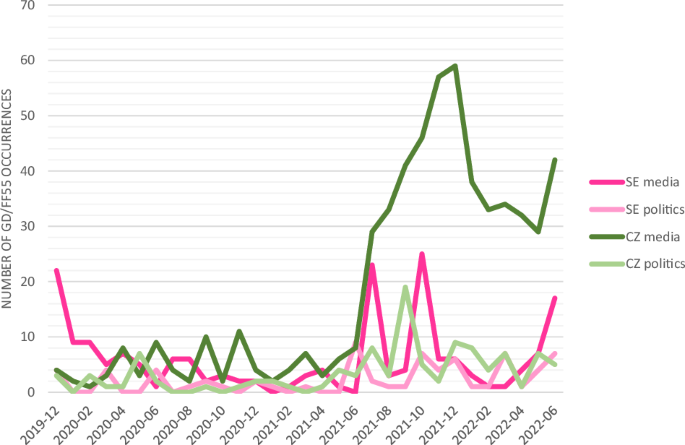

It is at first important to notice the global differences between the Czech and Swedish media and political discourses. Figure 1 summarises how frequently the searched key terms EGD, FF55 and their translations appear.

Observation of the intensity of the discourse suggests that it does not correspond to the perceived importance of EGD as a priority for the EU. The chart shows that when the EGD was announced, the Swedish media reported on it extensively, but it did not attract much attention in Czechia or among Swedish politicians. In Czechia, almost no media coverage could be observed until July 2021, when the FF55 package was proposed. Since then, in contrast, the number of occurrences of the terms has been skyrocketing. Also, the Swedish media has paid more attention to the EGD/FF55. The EGD became a hot topic before the Czech parliamentary elections in September 2021, but after the elections, interest in them dropped again. Even the war in Ukraine has not changed this trend. Increasing coverage can be seen again at the end of the reporting period in June 2022, when the EU ministers agreed on new energy efficiency and renewable energy targets for 2030.

However, the increase in the intensity of media discourse in Czechia in 2021 may be related to another fact. Russia started to reduce gas inflows to European markets as early as the turn of May/June 2021 (which could have been a step taken in preparation for the aggression against Ukraine) and this led to manipulations of higher gas prices. Thus, energy prices in Europe rose during the summer and autumn of 2021 (when the threat of a Russian invasion of Ukraine becomes imminent, the issue of energy prices ceases to be crucial).

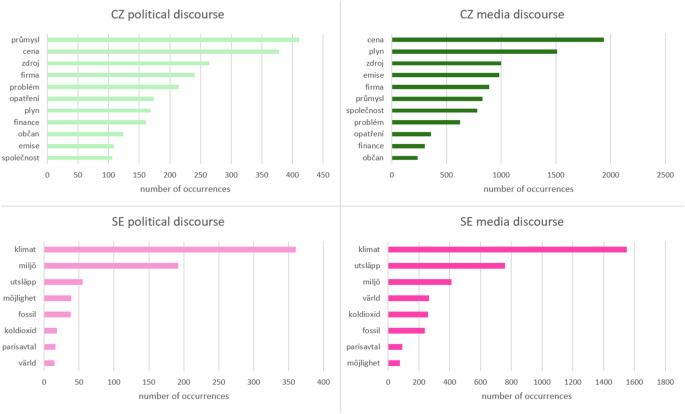

Subsequently, a comparison was made of the overall occurrence of keywords in each type of discourse in the countries examined (see Fig. 2).

The comparison of the total occurrences of the keywords across the countries and types of discourse. Translation (y-axis, top to bottom): CZ political discourse: industry, price, resource, company, problem, measures, gas, finances, citizen, emissions, society. CZ media discourse: price, gas, resource, emissions, company, industry, society, problem, measures, finances, citizen. SE political discourse: climate, environment, emission, possibility, fossil, carbon dioxide, Paris agreement, world. SE media discourse: climate, emission, environment, world, carbon dioxide, fossil, Paris agreement, possibility. Source: Compiled by the authors.

In the political and media discourse, the accentuated topics differ for the observed countries quite substantially: (1) Whereas in the Czech political discourse, words such as “price“, “industry” and “firms” are the most frequent, the Swedish discourse highlights the scientific dimension of climate change (“emissions”, “environment”, “climate”). (2) An interesting comparison can be seen when Czech politicians refer to the EGD as a “problem”, while it is framed as an “opportunity” in Sweden. (3) Also, the frequency analysis shows that “citizens” are a frequently debated topic in the Czech media and politics, but the topic does not appear with such a frequency in Swedish discourses.

Adjusting the calculation according to the scoring formula applied to the observed data set (see Equation 1) allows us to present more detailed results, which are included in the Table 1.

From the results thus obtained, the following can be stated: (1) In texts from both countries, climate-related issues (e.g., the climate package) are predominant in the direct proximity of the terms EGD and FF55, but it seems that the framing and importance of this topic are different (see the qualitative part of the paper). (2) In addition, the specificities of both countries need to be observed. Although the word “problem” appears repeatedly in the Czech media and political discourse, it is not positioned in the immediate vicinity of the term EGD or FF55. Therefore, it can be argued that the association is looser and based on a broader context, which will be further analysed in the qualitative section (see the discussion of the topos of a financial burden). (3) Another tendency is the high number of occurrences of the words “citizen” and “company” in the Czech texts, but not in the Swedish ones. (4) While in Czechia the issue of coal is often associated directly with the EGD, in Sweden the issue which the EGD is most often associated with is deforestation. These differences confirm a specific context of the reality of the energy sector and the economies of the countries examined.

Moreover, the proximity of the words in the discourse confirms that the Czech economy is energy-intensive, which is related to the position of industry in the EGD generation. Czechia is still dependent on the coal industry and the automotive industry (Škoda as part of the Volkswagen concern) plays a key role. This seems to lead to scepticism about the possibilities of energy transition, including a strong voice of climate change deniers (see e.g., the 2008 book by the former Czech President Václav Klaus “Blue Planet in Green Shackles”, published with the financial help of the US libertarian/climate denier Competitive Enterprise Institute (Bolkestein, 2008) and later translated and distributed in Russia by LukOil). Hence, Czechia´s energy sector has been closely tied to Russia. Until 2022, it was highly dependent on Russian gas, especially at the household level. In terms of nuclear energy, even after Russia’s aggression in Ukraine, nuclear fuel was supplied to Czechia (however, the final 3 deliveries were made with Westinghouse being the new supplier).

This is not the case for Sweden, which is not dependent on energy from Russia, and the complete cut-off from Russian supplies has not had major consequences for it (there is no feeling that it had to rely on “cheap Russian energy”). In Sweden, the car industry has also been a central political factor in the past (Volvo, Scania, Saab), but its role has recently diminished, and the Swedish economy is not dependent on it. Volvo’s sales to China and the preference for e-vehicles may also play a role. Sweden’s energy mix is already very green, and the country, therefore, benefits greatly from EGD, not least because of its mining and metal industries (raw materials and technology needed to implement EGD).

The results of qualitative analysis of the media and political discoursesThe entry-level qualitative analysis: prominent topics

In continuation of the quantitative analysis, which has shown similarities, but also several specificities of both countries’ discourses on a micro level, a broader qualitative approach needs to be taken. Within the first level of the qualitative analysis, the main topics were searched for. These were identified according to the topics related to the EGD as presented by the EU itself (EC, 2022) and with the additional help of the keywords found in the quantitative analysis. The results are shown in Table 2.

The findings again show some differences. Firstly, while the predominant topic in Czechia was energy, it was the climate in Sweden. Of course, these two topics are interrelated, but the different framings in the two countries are quite evident. Whereas Czechia emphasised the need to ensure sufficient energy sources for reasonable prices to protect Czech citizens and companies, Sweden pointed out the need for all energy to be fossil-free and clean. Secondly, in line with this, Czechia insisted on EU funds supporting its transition towards clean energy so that the financial burden on its businesses and citizens would be eliminated, whereas Sweden refused any new funds since they would only prolong the transition and enhance emissions. Specifically, the Czech Minister of Industry Karel Havlíček stated that it is key for the EU to acknowledge nuclear energy as a sustainable source because otherwise nuclear investments would not be favourable and energy prices might increase for Czech customers, which would be unacceptable (Havlíček, 2020). Similarly, the Czech Minister of Environment, Anna Hubáčková, was explicitly in favour of a new social fund to help compensate poorer families for the costs of the beginnings of the transition towards a low-emission economy (Hubáčková, 2022). Contrarily, the Swedish government insisted that there is “no need for additional budgetary mechanisms since extensive EU funds are already allocated to the climate transition within the EU budget and the recovery plan,” and “that the transition to fossil-free energy resources needs to be accelerated” (Government Offices of Sweden, 2021a).

Thirdly, another relevant issue discussed in both countries is transport, particularly in connection with electric cars. In Czechia, some politicians were cautious with regard to setting the deadline in 2035, which is presented as too ambitious. The Minister of Environment Richard Brabec even claimed that if Czechia demonstrated an active preference for electric cars too early, people might choose to keep their old cars instead of buying a very expensive electric car, which would lead to unintended consequences (Brabec, 2021). Also, Prime Minister Petr Fiala preferred a slower ban on cars with a combustion engine (Fiala, 2021). As for Sweden, the Swedish Minister for Climate Annika Strandhäll commented on the EU plan for stopping the production of cars with a combustion engine as follows: “I am very content with what we have achieved, even though Sweden wanted to go even further” (Strandhäll, 2022).

Overall, various aspects of the EGD were discussed in both countries. Also, all initiatives of the EU connected to the EGD and the FF55 were covered in both countries at least briefly (such as the circular economy, chemicals, batteries, or hydrogen power), which further demonstrates the relevance and importance of the EGD even though the attention paid to the EGD fluctuates diachronically and topics are framed differently in both countries as demonstrated in more detail below.

The in-depth qualitative analysis: argumentative strategies

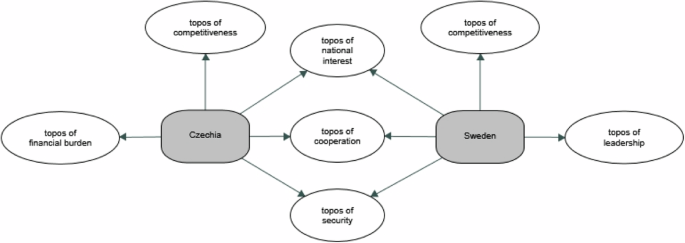

Pertaining to the in-depth level of analysis, seven topoi were developed to analyse and compare the discourses in Czechia and Sweden—see Table 3.

The results of the analysis point to the following differences in the discourses in the two countries and their argumentative strategies. Firstly, in Czechia, the most common argumentative strategy draws on the financial impact of the EGD on the Czech public. The topos of a financial burden is employed by both politicians and the media. The crux of the matter is that neither the Czech citizens nor Czech companies must suffer from the impact of the EGD. As stated above, Czech representatives require nuclear power and temporarily also gas to be considered sustainable, which should help solve the problem of increasing energy prices. Specifically, vulnerable customers should be protected from energy poverty (Ministry of Industry and Trade, 2021a; Ministry of the Environment, 2022a). Often, Czechia is compared to Germany within this topos: “given the energy mix, the structure of the economy and industry as well as the purchasing power of our citizens, the EGD commitments are much more demanding for Czechia than for Germany or other countries” (Ministry of Industry and Trade, 2021b). Hence, it is the financial implication that seems to be perceived problematically rather than the EGD as a whole. Moreover, the topos of a financial burden is usually framed as rational: “We are not saying no; we are pragmatic. We can´t end up like the yellow vests in France, where President Macron increased gas prices and the society did not accept it” (Brabec, 2021). This framing is not present in Sweden at all. Contrarily, the financial burden is perceived as necessary to save the climate. The message in both the political and the media discourse in Sweden is that if we do not invest now, the cost will be higher later: “A fiscal policy that lacks a clear green and long-term perspective will otherwise have disastrous consequences when the bill for the climate crisis comes” (DN Debatt, 2020).

Secondly, this contrast is mirrored in two following argumentative strategies, namely in the topos of competitiveness promoted by Czechia and the topos of leadership emphasised by Sweden. The Czech politicians and media are afraid that the EGD might decrease the competitiveness of Czechia and the EU as a whole since it is too ambitious, and if the biggest polluters such as China and India do not follow our demands, the EGD’s impact will be counterproductive. As Prime Minister Babiš said: “the EU cannot achieve anything without the participation of the biggest polluters, e.g., China and the USA (…). Despite these facts, the European Commission suggests further dangerous proposals (…). We do not know whether these goals [the FF55] are too ambitious” (Babiš, 2021). In Czechia, the topos of leadership is virtually missing. The fear of losing competitiveness is much more prominent than the urge to lead the rest of the world. Czech representatives claim that it will be very complicated for Czechia to fulfil all the EGD requirements as it is an industrial country heavily reliant on coal with an underdeveloped low-carbon economy. As Minister Havlíček argued: “We will rigorously require such a plan that will not harm the competitiveness of our car industry as it is key to the Czech economy” (Dvořák, 2021). This is not to say that nobody in Czechia considers the EGD as a great opportunity for modernisation and technological change, or a great opportunity to move forward by shifting the country’s mindset, but the people with such views are rather businessmen than politicians (Gallistl, 2022). The Swedish understanding is completely opposite. Swedish representatives claim that the EGD might increase the competitiveness of the EU, and that the EU must lead the rest of the world. Even Sweden itself is often pictured as a role model (Lövin, 2019). Similarly, the Swedish Minister for Infrastructure Tomas Eneroth said that the FF55 package “is nothing that inhibits competitiveness. It strengthens it” (Eneroth, 2021).

Thirdly, contrary to the first three topoi, there is rather an agreement on the following three topoi between the two countries. The topos of national interest is prominent in both countries. Czech representatives emphasise the need to allow nuclear energy and gas as transitional resources. This issue dominates both discourses in Czechia with an overall agreement among all the political parties (Czech News Agency, 2022). The goals of the EGD/FF55 are accepted but the emphasis is on Czechia as an industrial country where renewables are not sufficient and hence, other resources must compensate for the loss of coal, which is to be no longer used by 2030 (Ministry of Industry and Trade, 2021c). All political parties stress that each MS is different, and each national energy mix should remain within the discretion of the respective country. Another frequent argument is that impact studies for the EGD are completely missing despite them being considered of utmost importance since the EGD will have an impact on “everything—the whole society, companies, each citizen” (Government of the Czech Republic, 2021a).

In Sweden, although the country also uses nuclear power, the requirement to allow it is more complicated since some political parties push for renewables and do not promote nuclear energy. This clash of priorities was most visible when Minister Lövin had to go to Brussels to demand that nuclear energy be included in the taxonomy, while she and her party (the Green Party) were against it (Davidsson, 2020). The Minister for Energy in the following government, Khashayar Farmanbar, considered nuclear energy too expensive in comparison to other alternative energy sources and called it neither green nor renewable. He is even more critical of natural gas, rejecting it being included in the taxonomy (Farmanbar, 2022).

Apart from energy, the topos of national interest is prominent within agriculture. In particular, Sweden protests against the EU legislation on forests and demands that forests remain within the national discretion. Although Sweden acknowledges that forests must be protected and serve the purposes of climate protection, it opposes the EU legislation to be too detailed. The government “believes that forestry policy is a national competence, [and] new proposals must be in line with the possibility of sustainable active forestry and detailed regulation at EU level of what should be avoided in sustainable forestry” (Government Offices of Sweden, 2021b). Even the Swedish EU Commissioner (responsible for home affairs, not agriculture) Ylva Johansson intervened that Brussels should not decide about Swedish forestry (DN Sverige, 2021a).

Fourthly, while Czech representatives are very open in demanding that Czech interests and particularities should be considered, Sweden protects its own priorities more subtly. However, the core of the argumentation is similar and even supported by the virtual non-existence of the topos of cooperation, which is dominant in the EU discourse (EC, 2022). It seems that even when the two countries agree on the EGD as such, they still give a strong preference to their own interests or values, be it the protection of industry in Czechia or being a leader in climate protection in Sweden. Cooperation seems to be backgrounded at the expense of national priorities.

Finally, and surprisingly, given how the EGD is presented by the EU and in academic debate, it is very rarely securiticised (Siddi, 2020a). The topos of security were occasionally employed in Czechia after the Russian invasion, when it was particularly linked to national self-sufficiency of energy resources (Hilšer, 2022) and achieving energy independence through nuclear energy and renewables (Government of the Czech Republic, 2021a). Nevertheless, the prevalent framing is rather energy- and climate-related in both countries.

For the results of the analysis see Fig. 3.

Discussion of political specifics, dynamics and the overall assessment of the energy discourse

Above, the main topics and argumentative strategies in the media and political discourse in each country were analysed. Below, an overall assessment will be carried out.

Pertaining to the diachronic development of the discourses, it must be stated that the governments changed in both countries during the years 2019–2022. However, while the official discourse in Sweden has stayed more or less consistent, a discursive shift was observed in Czechia. Even though the government led by Andrej Babiš´s populist movement ANO, frequently criticised the EGD to the point of saying that it might be a disaster for Czechia, this was highly dependent on the context in which the statement was uttered (e.g., tearing the EGD to shreds during talks with the Hungarian Prime Minister Viktor Orbán while being open to it when talking to Ursula von der Leyen about the National Recovery Plan) (Government of the Czech Republic, 2021b). Also, Babiš agreed with the EGD during the European Council meeting and admitted that climate change is a challenge that must be solved (Government of the Czech Republic, 2021c). His successor Petr Fiala and his government were more open to the idea of the EGD, which was even mentioned as a priority in their governmental programme and considered as an opportunity to invest in sustainable development and modernisation of the economy, while nuclear power and renewables were explicitly mentioned as means to achieve the EGD goals (Government of the Czech Republic, 2022a). In Sweden, both Stefan Löfven and Magdalena Andersson and the relevant ministers welcomed the EGD openly and supported an even more ambitious plan (DN Sverige, 2021b). In both countries, only a few actors explicitly reject the EGD, mostly representatives of right-wing populist parties (the Czech SPD and the Swedish Democrats). In Czechia, these were complemented by the President Miloš Zeman, who repeatedly claimed that the EGD should be abolished (Jeřábková, 2022).

Also, for the investigated period, two relevant milestones can be identified: (1) the Covid-19 pandemic and (2) the Russian invasion of Ukraine. In Czechia, since early 2020, when the pandemic started, many press statements of Czech politicians were opened with the topic of Covid-19, which was later succeeded by the EGD as the number two priority. On these occasions, the EGD was presented as a potentially important change for citizens and companies. The government and trade union representatives often emphasised that they would not allow people or companies to suffer from the EGD measures financially. Specifically, energy poverty was discussed heavily (Government of the Czech Republic, 2022b).

In Sweden, neither the pandemic nor the Russian invasion caused a change in the numbers or nature of the relevant published statements and articles. Most of the articles and statements studied here were published shortly after the EGD and the FF55 package had been presented, i.e., in December 2019 and July 2021. These were of a rather informative nature, explaining what the initiatives are about and how the leading Swedish representatives feel about them. Also, the Czech media devoted much more attention to the Russian invasion of Ukraine than the media in Sweden, which seems to be logical, since Czechia is much more dependent on Russian energy imports than Sweden.

Similarly, the two countries’ argumentative strategies also differed a lot after February 2022. While Sweden claimed that a quicker transition towards renewable energy and more investments into the EGD is needed, Czechia was more cautious regarding the EGD and insisted that coal should be allowed, at least temporarily, since renewables would not be sufficient. On the other hand, as Minister Anna Hubáčková said, the war in Ukraine does not mean that Czechia will not focus on topics related to the environment, that Czechia might postpone the fulfilment of the EGD or that Czechia would return to coal (Ministry of the Environment, 2022b). Thus, despite their different framings, both countries wanted to preserve the EGD. In Czechia, another topic was identified after the invasion, which was completely missing from the Swedish discourse, namely disinformation. On many occasions, it was mentioned that the EGD is criticised by Russian trolls and thus used as a weapon against the EU and renewables and, vice versa, in favour of Russian gas imports. However, overall, both countries emphasise that neither Covid-19 nor Ukraine should prevent the EGD from being implemented.

Moreover, no major differences were identified between the political and media discourses in each country or across the selected media outlets. The overall framing remained consistent with a few notable exceptions such as in case of iDNES.cz, which was much more sceptical about the future of the EGD after the Russian invasion of Ukraine. The outlet paid attention to statements and opinions emphasising the need to make the EGD less ambitious and accept nuclear energy since renewables are neither sufficient nor reliable in Czechia, or explicitly rejecting the EGD as too radical or downright crazy. Other sources of data were more restrained and fact-based even when expressing dissatisfaction with the EGD. Interestingly, even a highly emotional politician, Andrej Babiš, often argued pragmatically about it. Although he criticised the EGD frequently, he did not forget to emphasise the need to protect the climate and that accepting the EGD means a lot of EU money for Czechia.

Overall, the perception of the EGD is rather positive in both countries. Hence, maybe surprisingly, the argumentation regarding the EGD is predominantly pragmatic in both countries. Albeit in Sweden, it is mostly explicit, while in Czechia it is often between the lines. Despite the agreement that the EGD is a good idea, the framing in the two countries differs. The hypothesis of the difference between the two discourses was thus only partially confirmed, particularly concerning the argumentative strategies. In Czechia, most of the analysed politicians argue that the idea of the EGD is good and that it is necessary and even inevitable to protect the climate and ensure clean energy, but they usually emphasise that it is necessary to take national specifics into account. In Sweden, national priorities are mentioned occasionally but overshadowed by the framing in which the EGD is desirable, but a more intensive plan should be enacted.