SANTA CRUZ — For Brook Thompson, her life’s work began in September 2002. It was then that, at the age of 7, Thompson stood witness to thousands of dead salmon lining both sides of the Klamath River in Northern California, near where she grew up.

The deaths were largely attributed to dams along the river that diverted water, causing the freshwater levels to become too low and warm, resulting in thousands of Chinook salmon — as well as steelhead and lampreys — from being unable to access their habitat above and contracted a widely spread parasite called Ich, or white spot disease. Due to salmon being a major part of Indigenous identities, many local tribes including the Yurok and Karuk — both of which Thompson is a member of — began protesting for the dams’ removal, which became a reality in 2024 with the eradication of four of the six dams along the Klamath River.

Thompson was present throughout all of this. She joined the protests at a very young age, went to college to study civil engineering and is working on her environmental studies Ph.D. at UC Santa Cruz.

“The 2002 fish kill has changed what I do for work, has been the trajectory of where I go to college and what I do as a whole to stop something like that from happening ever again,” she said.

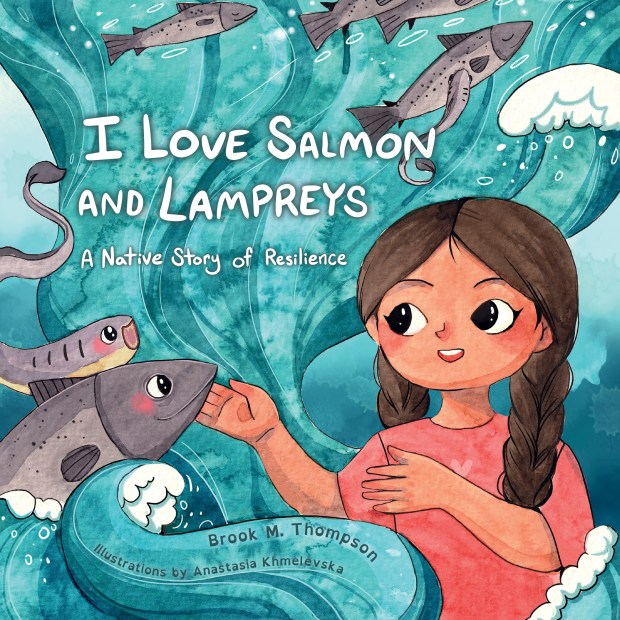

Thompson shared those life experiences in her new children’s book, “I Love Salmon and Lampreys: A Native Story of Resilience,” which will be published March 4.

“I Love Salmon and Lampreys” by Brook Thompson. (Contributed – Heyday Books)

“I Love Salmon and Lampreys” by Brook Thompson. (Contributed – Heyday Books)

Thompson pointed to a few reasons as to why she wrote a children’s book — as a culmination of the dams’ removal, a way to share her story with her younger cousins, the way her tribes protested and also her decision to go to college.

“I’m one of a few folks in my family on my Native side who has gone to college,” she said. “I get a chance to show them how going to college has helped me pursue this idea of dam removal in addition to explaining how this traumatic event happened.”

Additionally, Thompson did not read a lot of books growing up which had Native representation, and the ones she did were set in the past.

“We’re current-day participants in society, and we’re currently here still working with the environment and to save it,” she said. “For me, it’s also recontextualizing what it means to be a current-day U.S. citizen and create diversity in children’s books.”

Thompson received a grant from the California Youth Council to pay artist Anastasia Khmelevska to serve as the book’s illustrator, which also gave her the push to finish the book. “I Love Salmon and Lampreys” tells Thompson’s story of growing up in a family that loved to fish and cook prior to the salmon die-off of 2002, and also follows her through her protests and studies, all while incorporating facts on salmon and lampreys.

Thompson grew up splitting her time between living in Portland, Oregon, with her mother and living on the Yurok Indian Reservation with her father in the community of Klamath. Located in Del Norte County at the northern tip of California, she lived near the mouth of the Klamath River, which was once the third largest salmon producer on the West Coast. Thompson has childhood memories of collecting rocks on the beach and getting up early to go fishing with her father.

“There’s this quietness where you just have the sound of the waves, and being on a boat early in the morning surrounded by fog is what comes to my mind when I think of the Klamath River,” she said.

Thompson’s family had been taking care of the river’s salmon for generations, and the day after a world renewal ceremony in 2002, where her tribe prayed for balance in the Earth, she and her parents were told that something was happening at the river.

“I went with my parents down to the shore of the Klamath at the mouth, and you just see piles and piles and piles of dead salmon lining both shorelines, salmon that were perfectly fine and alive the night before,” she said.

Thompson said the world needed to know what had happened and told her mother to take photos. In Indigenous cultures, salmon are more than just food and recreation.

“It’s this real connection to my family, and it’s this connection with my ancestors where these fish I’m eating have had relationships and have kind of an agreement with my ancestors,” she said. “They took care of each other for generations, so the fish I’m eating are the descendants of the fish that had a relationship with my ancestors. I feel that love and care that gets put into them, like when you have someone who loves you like a mother or grandmother who cooked you your favorite meal, and it feels special. That’s how I feel about the salmon in the river. All of that was lost within just a few hours for reasons outside of the tribe’s control.”

Thompson became anxious this would happen every year.

“I remember the smell of decaying flesh in sunlight on the shore and the devastation of being in disbelief of something that’s never happened in our oral history,” she said.

The salmon kill triggered a large movement among local tribes to push for the dams’ removal, and Thompson attended protests from the get-go. It also inspired her to go to college to study civil engineering for an understanding of how infrastructure works and why dams are constructed, in an effort to strengthen her beliefs that they should be taken down.

“I felt like I could get the other perspective, combining the math and science side with my tribal understanding,” she said.

In 2018, Thompson enrolled at George Washington University in Washington, D.C., and also became a policy intern for the U.S. Senate Committee on Indian Affairs while interning for New Mexico Sen. Tom Udall.

“I got to sit on the other side of the table at some of the policymakers we were trying to ask for help from,” she said. “I got to have that broad experience of policy mixed with engineering, higher education and my tribal traditional knowledge that I’ve seen firsthand.”

Ten years ago, Thompson began writing the first draft of “I Love Salmon and Lampreys” and revised it over the years as she learned more about writing children’s books. The removal of the Iron Gate Dam and other hydroelectric dams along the Klamath River in 2024 pushed her to finish the project.

“The dam removals are the spark of hope I’ve really needed,” she said. “Seeing this thing I’ve been wanting my entire life finally come to fulfillment is honestly more than I ever could have asked for.”

Thompson made sure to give equal billing to lampreys, eel-like fish that predate dinosaurs and have mouths that serve as suction cups and allow them to catch free rides on salmon.

“Lamprey are such a cool creature and super important to my tribe and culture,” she said. “I feel like not a lot of people know what a lamprey is, and just because they’re not commercially sold in stores to eat, I still think people should care about them and understand this amazing creature, if not kind of scary creature, we have on the West Coast, and also want to protect them just as much (as salmon).”

Thompson hopes readers understand that with enough action and community support, change is possible.

“Even as a kid, you can make a difference,” she said.

“I Love Salmon and Lampreys” will be published March 4 by Heyday Books.