President Donald Trump said Friday that the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services will take on special education.

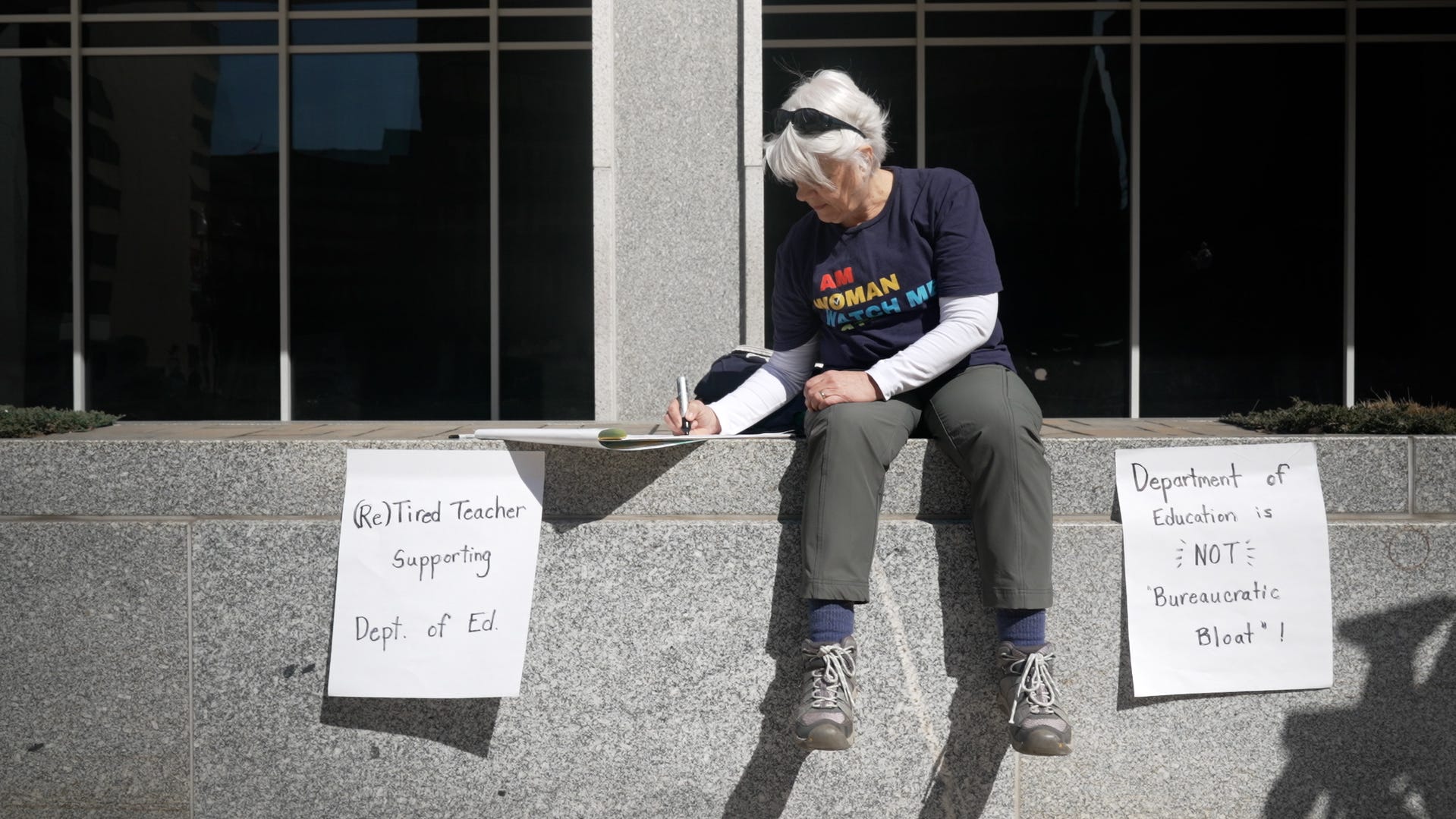

‘Makes me cry’: Teachers, students react to Education Dept. cuts

Former students and teachers are reacting to the Trump administration’s funding cuts and layoffs at the Department of Education.

President Donald Trump‘s Thursday executive order dismantling the U.S. Department of Education leaves wide open questions about whether the legal rights of students with disabilities will be protected.

Trump said Thursday at the White House that resources for students with disabilities and special needs “will be fully preserved” and those responsibilities traditionally handled by the Education Department would be transferred to staffers at another federal agency.

On Friday, Trump clarified that special education will be handled by the Department of Health and Human Services. That agency currently oversees Section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act of 1973, which prohibits discrimination for students with disabilities.

The Department of Education has long enforced the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act, which guarantees about 7.5 million children with disabilities in the U.S. a “free appropriate public education.” The law protects these students from being turned away at public schools and requires schools to provide them with Individual Education Programs, or IEPs, to help them thrive academically.

For years, the Education Department has dispersed federal dollars to states to spend on students with disabilities, conducted national research by analyzing state-to-state data and collected and investigated special education-related civil rights complaints.

Congress will ultimately decide whether the Education Department can be completely shuttered, but the Trump administration has already begun to shrink the agency and its functions through a workforce reduction. Hundreds of staffers who conducted academic research and investigated civil rights complaints at the department were laid off in mid-March.

Supporters of Trump’s move have applauded him for reducing the federal government’s hand in education.

“Today, President Donald Trump delivered one of the most influential reforms yet of his presidency: reducing the size of the Department of Education and returning education back to state control,” wrote Nevada Gov. Joe Lombardo, a Republican, in a statement. “With his Executive Order, President Trump has boldly reimagined what education can – and should – look like in our country.”Still, special education experts worry about the uncertainty ahead for schools and the families of students with disabilities who have relied on the Education Department’s services.

Many questions remain unanswered about how special education programs will be funded and researched or whether schools will be held accountable for providing adequate services to students with disabilities, said Carrie Gillispie, a senior policy analyst with the education policy program at the national liberal-leaning think tank New America.

The U.S. Department of Education did not respond to multiple queries from USA TODAY.

Here are a few ways the modern Education Department has aided and provided assistance to students with disabilities over the years and the concerns that have sparked since Trump took office.

Disperse and oversee federal funding

The U.S. federal government is obligated by the Individuals with Disabilities Act to administer funds to states to spend on special education and students with disabilities between the ages of three and 21.

The Education Department currently disperses the money and makes sure states spend the money on students with disabilities. The agency spent $15.5 billion on special education programs for students with disabilities in fiscal year 2024, according to Pew Research Center.

Trump has not said there will be any federal cuts to special education funding following the executive order or specified how HHS would disperse funding. But the uncertainty has ignited confusion and worry among education leaders who say states need all the funding they can get for students with disabilities.

Many states, tight on cash, are in need of the federal money that the Department of Education allocates to students with disabilities, said Daniel Pearson, executive director of a teacher-led nonprofit organization Educators for Excellence.

If funding remains the same, Pearson said he’ll be watching to see if it comes with the same stipulations to spend on students with disabilities.

“There could be a world where funding is not decreased, but it could go to states as block funding so states can allocate how the money is spent,” he said. “The problem is that the accountability measures are built in through the federal department.”

Rep. Jahana Hayes, D-Conn., called Trump’s executive order to dissolve the Education Department “illegal” in an emailed statement and said any threat to the federal government’s legal obligation to provide services and funding to students with disabilities will have consequences.

“Two things will happen: either local communities will have to make hard choices about what other resources they must cut to meet their legal obligation to provide services, or local taxes will increase to replace the funding the federal government will no longer be providing to districts,” Hayes said.

Investigate civil rights complaints

The Education Department’s Office for Civil Rights for years has collected and investigated civil rights complaints related to students with disabilities in the nation’s federally funded schools. This includes complaints of discrimination or abuse.

Typically, the Office for Civil Rights investigates a complaint and finds out whether a school or district has violated its obligation to serve students with disabilities. If they find a violation, they can enter into a voluntary agreement with the school or district to resolve the issue without legal intervention.

The functions of that office are in limbo.

Staffers at the agency paused their work on disability-related discrimination cases when Trump entered office in January.

The Trump administration lifted a pause on the cases on Feb. 20, according to an internal memo.

Then it laid off 243 people from the federal office in March – gutting its ability to process complaints as it’s done before.

It’s unclear what will happen to existing cases and whether HHS will handle disability-related civil rights complaints in schools.

The National Center for Youth Law has filed a federal lawsuit challenging the decision “to effectively stop investigating civil rights complaints.”

“Failing to investigate civil rights complaints is a betrayal of students and families across the country, all of whom deserve justice,” wrote Shakti Belway, the group’s executive director, in an emailed statement.

Conduct research about students with disabilities

The Education Department for years has collected state-level data about how many students with disabilities they serve, how well they provide education to those students and which students are underserved. The federal agency’s Office of Special Education has reported to Congress annually about how students with disabilities are performing in schools.

This level of accountability is crucial to achieving equity across states and for states to learn from one another about what methods work best for identifying and serving kids with disabilities, said Gillespie, who has worked in schools in North Carolina and Massachusetts.

But the Trump administration recently gutted the Institute of Education Sciences, the federal agency’s research arm. IES staffers conducted congressionally mandated research about special education and other educational progress. All of those staffers were laid off in the recent federal workforce reductions.

It’s also unclear how or if research on students with disabilities will be administered moving forward.

The research freeze especially concerns Gillispie.

She’s seen how special education can look different from state to state and said families of students with disabilities can move from one state to another and experience different types of support – sometimes for the worse.

“Some states are better at finding kids who need those services more than others,” Gillispie said. “And once they find children who might be eligible, they might assess those children differently.”

She fears that the problem could grow at the expense of students without adequate federal research.

Contributing: Zach Schermele; USA TODAY

Contact Kayla Jimenez at kjimenez@usatoday.com. Follow her on X at @kaylajjimenez.