We compared global media coverage and internet search interest in COP15—which resulted in the Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework—with COP27, a climate-focused conference, and the popular American singer Taylor Swift. Despite the critical environmental and societal implications of biodiversity loss, COP15 received significantly less attention, even in highly biodiverse countries. Addressing this attention shortfall will be crucial for building the awareness and advocacy needed to achieve global biodiversity goals.

On December 1st, 2022, Dialogue Earth, an organisation focused on deepening public understanding of environmental issues through science communication, published an article calling COP15—the 15th Conference of the Parties to the United Nations Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD)—the most crucial biodiversity conference in a decade1. In the article, author Mike Shanahan, a writer and biologist, described COP15 as a pivotal moment for biodiversity conservation, highlighting the importance of the Global Biodiversity Framework2 and its ambitious set of global action targets designed to reverse biodiversity loss by 2030. COP15’s significance for tackling biodiversity loss—a global challenge with profound implications for the environment and society—resonated more broadly. A day later, on December 2nd, 2022, Allianz Global Investors3 argued that COP15 could be “nature’s Paris moment,” drawing a compelling parallel to the 2015 Paris Agreement adopted at COP21—the 21st Conference of the Parties to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC)—which had sparked major media attention and hopes for unified climate action.

Initially scheduled for October 2020 in Kunming, China, the path to COP15 was not without obstacles4. The conference was delayed multiple times due to the COVID-19 pandemic, with its final phase ultimately taking place in Montreal, Canada, in December 2022. As negotiations unfolded, tensions ran high, with some Global South countries on the verge of withdrawing2. Yet, in spite of these challenges, COP15 concluded with the adoption of the Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework—a landmark agreement widely recognised as crucial in the fight to halt biodiversity loss2,4.

Even with COP15’s significance and its success in bringing nations together under a shared framework with concrete action targets for potentially reversing biodiversity loss by 2030, it did not receive the same level of media attention as climate-focused UN summits such as COP27—the 27th Conference of the Parties to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC)—held just a month earlier in November 2022 in Sharm El Sheikh, Egypt. The lower media coverage of COP15 represents a missed opportunity to communicate the urgency of biodiversity action to the public, organisations, decision-makers, and other key stakeholders whose active support is critical for achieving the global biodiversity targets5. Research on the media’s role in raising awareness and driving action for environmental causes has shown that media are critical in addressing these issues5. While increased media coverage does not always directly translate into greater mobilisation6,7—due to several influencing factors such as content, tone, framing8, and audience preconceptions7,8—it is widely recognised that sustained and widespread media coverage is essential for tackling environmental issues6,8,9. Moreover, research on climate change media coverage has shown that high-profile international meetings such as COPs serve as focusing events and are, therefore, major drivers of media attention6,10,11. Given COP15’s importance and the Global Biodiversity Framework’s role in addressing biodiversity loss, it provided a key opportunity to elevate biodiversity on the global agenda.

To document the disparity in media attention, we used Media Cloud, an open-source platform for media analysis, to analyse 227,940 media stories published in 6939 outlets across more than 80 languages worldwide, contrasting media coverage of COP15 with that of COP27. Our analysis, spanning October 2022 to January 2023 (a month before COP27 and a month after COP15), also included media coverage of the highly successful American singer Taylor Swift, whose tenth album, released in October 2022, gathered widespread attention. With millions of people streaming hits like “Cruel Summer”, Taylor Swift’s popularity underscores the intense competition for media focus and highlights how public attention can shift away from urgent global environmental issues.

We found a stark imbalance in media attention: overall, COP27 received nearly seven times more coverage than COP15 (150,371 vs 22,422 media stories, respectively; Fig. 1A), with the disparity being substantially larger in many countries (Fig. 2A). COP15 coverage was noticeably lower in almost every country (Fig. 2A), with few exceptions, such as China and Canada—unsurprisingly, given China’s role in presiding over the negotiations and Canada’s role as host in Montreal. Media coverage of COP15 was also overshadowed by that of Taylor Swift, who attracted more than twice the media stories (55,147; Fig. 1A). This pattern was evident not only in the United States—Taylor Swift’s home country—but also across much of Europe, Latin America, and Asia (Fig. 2B). Highlighting this striking imbalance is the fact that Taylor Swift received more media attention on October 21st, the release date of her tenth studio album, than COP15 did on its opening day, December 7th, and as much as COP15 did on its closing day, December 19th (Fig. 1A).

The top panel (A) illustrates the total number of media stories in the Media Cloud database for COP27 (blue line), COP15 (green line), and Taylor Swift (red line). The bottom panel (B) shows the total number of internet search trends worldwide for each of the three terms during the same period, according to Google Trends.

Worldwide media coverage of (A) COP27, normalised relative to media stories on COP15 (a ratio > 1 indicates higher COP27 coverage), and (B) Taylor Swift, normalised relative to media stories on COP15 (a ratio > 1 indicates higher coverage of Taylor Swift). Counties with no articles on COP15 in the Media Cloud database are shown in grey, while those with no articles on any of the three search terms are shown in white.

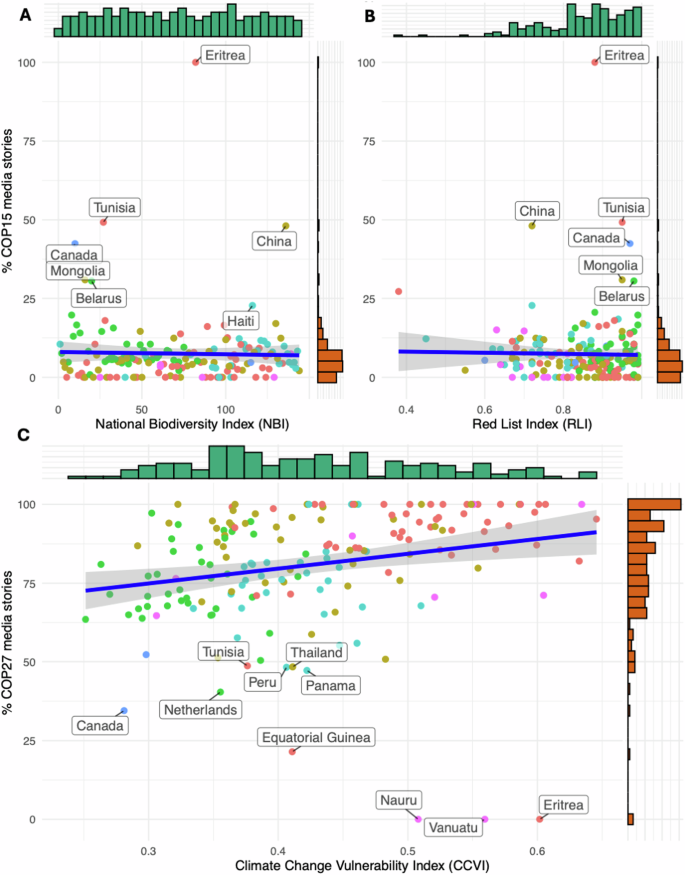

Despite the observed imbalances, one might expect that media outlets in countries with higher biodiversity levels would show a greater interest in COP15, considering its significance in setting the action targets for addressing biodiversity loss. However, we found no significant relationship between the countries’ National Biodiversity Index (NBI) and their media focus on COP15 (r = −0.03, pvalue = 0.73, n = 160 countries; Fig. 3A), measured as a percentage of the articles covering COP15 as opposed to all three terms included in our analysis. Similarly, we found no relationship between the countries’ Red List Index (RLI)—an indicator of the proportion of species at risk—and the media focus on COP15 (r = −0.02, p-value = 0.79, n = 200; Fig. 3B). However, we observed a moderate but statistically significant relationship between the countries’ Climate Change Vulnerability Index (CCVI) and COP27 coverage (r = 0.23, p-value = 0.002, n = 179; Fig. 3C), indicating that media in countries more vulnerable to climate change tended to report more extensively on COP27. Notably, this relationship was not stronger because several countries, such as Oman and Botswana, reported extensively on COP27, beyond what would be expected based on their CCVI value. Conversely, COP15 received low coverage across most nations, even those with high NBI or RLI scores (Fig. 3A, B).

Media coverage of COP15 in each country was not related to its (A) National Biodiversity Index (r = −0.03) or (B) Red List Index (r = −0.02). In contrast, media coverage of COP27 was moderately related (r = 0.23) with its (C) Climate Change Vulnerability Index. The green histograms represent the distribution of the three index values across countries, while the orange histograms show the distribution of the percentage of media stories. Points are colour-coded to indicate the continent of each country: red circles = Africa, green circles = Europe, blue circles = North America, tan circles = Asia, cyan circles = Latin America and the Caribbean, and pink circles = Oceania.

To examine whether the reduced global media focus on COP15 was mirrored, or potentially even driven to a certain extent, by public interest, we analysed global internet searches during the same period using Google Trends12, focusing on news-related searches for COP15, COP27, and Taylor Swift. Internet search patterns revealed a similar trend (Fig. 1B): COP27 attracted significantly more attention than COP15 (but see12 and the response13). Searches for Taylor Swift were the highest overall, with distinct peaks on key dates (Fig. 1B)—such as the release of her album on October 21st, 2022, and the sale of tickets for her Eras Tour on November 15th, 2022, which famously caused the Ticketmaster platform to crash due to overwhelming demand.

These patterns document that COP15, a conference of global significance which resulted in a historic agreement4 outlining ambitious action targets to address biodiversity loss, has received limited attention. Past analyses focusing on major media outlets in the US, UK, and Canada14,15 have documented a similar reduced focus on biodiversity loss compared to climate change. Multiple factors are believed to drive the disproportional attention, one being that climate change has benefited from a clear narrative focus16, with a measurable headline target—keeping warming under 1.5 °C—that lends itself to concise messaging. Biodiversity loss, on the other hand, lacks a universally relatable target. Recognising the value of such clear target for media and stakeholder engagement, at COP15, the “30×30” initiative (protecting 30% of the planet by 2030) was proposed as a potential rallying goal. However, while the “30×30” target holds promise, it remains contentious. Protecting 30% of land and oceans may not be sufficient to halt biodiversity loss17 and will be difficult to implement in some regions also due to its potential social implications. Furthermore, the “30×30” target is only one of the several key targets associated with the Global Biodiversity Framework, and does not universally encapsulate conservation objectives in the same way the 1.5 °C climate target does.

Another possible reason for the reduced media attention on biodiversity loss is that, unlike climate change—which can manifest through dramatic mediagenic events like floods and wildfires18 that resonate strongly with local audiences—the impact of biodiversity loss tends to be more gradual, subtle, and indirect18, making it less suited to capturing media attention, which tends to focus on event-driven stories.

Institutional support for climate change action has also been important and helped drive climate awareness. The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), established in 1988, was pivotal in framing climate change as a global crisis19, and its flagship assessment reports received substantial media attention6. The IPCC’s work earned it a Nobel Prize9 in 2007, and its collaborations with influential public figures, like former U.S. Vice President Al Gore6, helped to elevate climate concerns into mainstream discourse9,20. This heightened visibility also contributed to the emergence of a vocal climate change activism movement, which research shows is another major driver of media coverage on climate change10. Biodiversity lacks a similar longstanding institution and analogous drivers of visibility. Although the Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services (IPBES) was established in 2012, it has yet to achieve the same public recognition and media presence19. Additionally, biodiversity lacks a comparable activism movement and the high-profile support of influential figures, including celebrities.

A BBC article published following the conclusion of COP15 in December 2022 underscored the reality that while UN climate summits tend to attract numerous world leaders and high-profile celebrities, such as Leonardo DiCaprio21, this is not the case for biodiversity-focused UN summits. COP15, despite its importance, was no exception; the large majority of the countries were at most represented by ministerial-level officials during the “high-level” segment of the meeting1. The absence of high-profile attendees has been already recognised as a key factor for the reduced media coverage, including by central figures of COP15 such as Ogwal Francis18. This issue is reflected also in our analysis: for example, we identified over 300 articles discussing King Charles’s intention to attend COP27—not only by UK media outlets but also foreign—demonstrating how high-profile figures’ interest in climate change serves as an opportunity to bring the topic to the public’s attention. That said, questions remain about the type of media coverage most effective in mobilising action and the factors influencing coverage levels, particularly across countries with differing sociocultural characteristics. While there is broad consensus on the importance of media coverage for addressing environmental causes22,23, these nuances require further investigation with the right analytical tools and datasets in future studies.

While the media’s extensive coverage of climate change14 is crucial in mobilising support for addressing the issue24, this disproportional emphasis risks overshadowing other critical environmental issues, potentially leading the public and stakeholders to perceive climate change as the sole pressing concern. Current scientific evidence contradicts this perspective, emphasising the severe societal and environmental consequences of biodiversity loss25. Moreover, this narrow focus could promote the incorrect idea that addressing climate change will also resolve other environmental challenges. In reality, many drivers of biodiversity loss, such as habitat destruction and degradation, operate largely independently of climate change26.

Given the media’s critical role in shaping public priorities23 and mobilising support24, the underrepresentation of biodiversity issues represents a missed opportunity to mainstream biodiversity issues and mobilise action for global conservation targets. Unlike many aspects of climate change, which can often be addressed through broad national policies (e.g., phasing out coal), biodiversity conservation frequently requires localised action27. Key stakeholders, including local authorities, communities, farmers, and landowners, need to be aware of the biodiversity challenges and the importance of addressing them to implement changes on the ground actively. Without sufficient local awareness and engagement, broader initiatives like the Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework risk falling short of their goals20.

Effective media coverage, including during high-profile events such as COP15, can strengthen biodiversity efforts by raising awareness of conservation issues and key initiatives to address them, particularly in biodiverse countries where conservation action is most needed. World leaders and influential figures can play a vital role in raising awareness of biodiversity loss, much like they have for climate change, by actively supporting key events such as major UN summits that have the potential to serve as focusing events for the media. Conservationists can also help address the limited media coverage of biodiversity issues by working closely with journalists to communicate compelling, mediagenic stories and solutions that resonate with local audiences. Equally important is making the connection between biodiversity and human well-being clearer, reinforcing the urgency of addressing biodiversity loss. By giving biodiversity equal prominence to climate change in public discourse—and even highlighting their interconnectedness to underscore potential synergies16—the media can help drive the political and social changes needed to achieve global environmental targets.

To quantify global media coverage, we used Media Cloud (https://www.mediacloud.org), an open-source platform for media analysis. Media Cloud allows searches across media sources in over 100 countries, with articles available in multiple languages dating back to June 1, 2020. For our analysis, we conducted three searches using the keywords “COP15,” “COP27,” and “Taylor Swift,” covering the period from October 1, 2022, to January 31, 2023 (one month before COP27 and one month after COP15). To track the media sources and identify the country in which they are based, we downloaded a sample of the URLs of the media stories resulting from each search. Media Cloud provides up to 1000 URLs for a given search term on a particular day within a period examined. For COP27, where media coverage repeatedly exceeded this limit, especially during the days of the conference, we obtained URLs for 38% of the total media stories (n = 57,000) published from October 1, 2022, to January 31, 2023. In comparison, for COP15 and Taylor Swift, we obtained 70% and 77% of the total media stories, respectively (n = 15,595 and 42,358). In addition to the URLs of the media stories, Media Cloud provides metadata such as the publication date, the media outlet’s name, and the abbreviation of the language in which the story was published. Using ChatGPT-4.o, we classified the 114,953 media stories we had obtained by country based on each outlet’s name.

To estimate each country’s interest in COP15 and COP27, we calculated the percentage of media stories covering COP15 and COP27, respectively, out of the total number of media stories in that country in our sample (i.e., the sum of stories about COP15, COP27, and Taylor Swift for each country). To ensure comparability of sample sizes, we downsampled COP15 and Taylor Swift to match the 38% sample size of COP27. We achieved this by randomly selecting articles for each term until the 38% threshold was reached. We repeated this process 1,000 times and used the country averages for the analysis presented in Figs. 2, 3.

As a proxy of each country’s biodiversity level, we used the National Biodiversity Index, available in Annex I of the Global Biodiversity Outlook 1 from the Convention on Biological Diversity (https://www.cbd.int/gbo1/annex.shtml). Additionally, we obtained the Red List Index (RLI)—a measure of species extinction risk used by governments to track progress in reducing biodiversity loss—available from the IUCN at https://www.iucnredlist.org/assessment/red-list-index. Similarly, to assess each country’s vulnerability to climate change, we used the Climate Change Vulnerability Index developed by the Notre Dame Global Adaptation Initiative (ND-GAIN). We measured public interest in each of the three terms in our analysis using Google Trends12 (https://trends.google.com), an open-access tool that quantifies the popularity of specific search terms across countries and over time. We restricted our search to the same period as our Media Cloud analysis (October 1, 2022–January 31, 2023). We ran a worldwide search using the same three keywords—“COP15,” “COP27,” and “Taylor Swift”—treating them as “search terms” as opposed to “topics” for consistency with Media Cloud.