By Vaibhav Raghunandan and Petras Katinas

Russian crude oil revenues rise 13% despite marginal rise in volumes, while France’s Russian LNG imports rose to 12 month high

Key findings

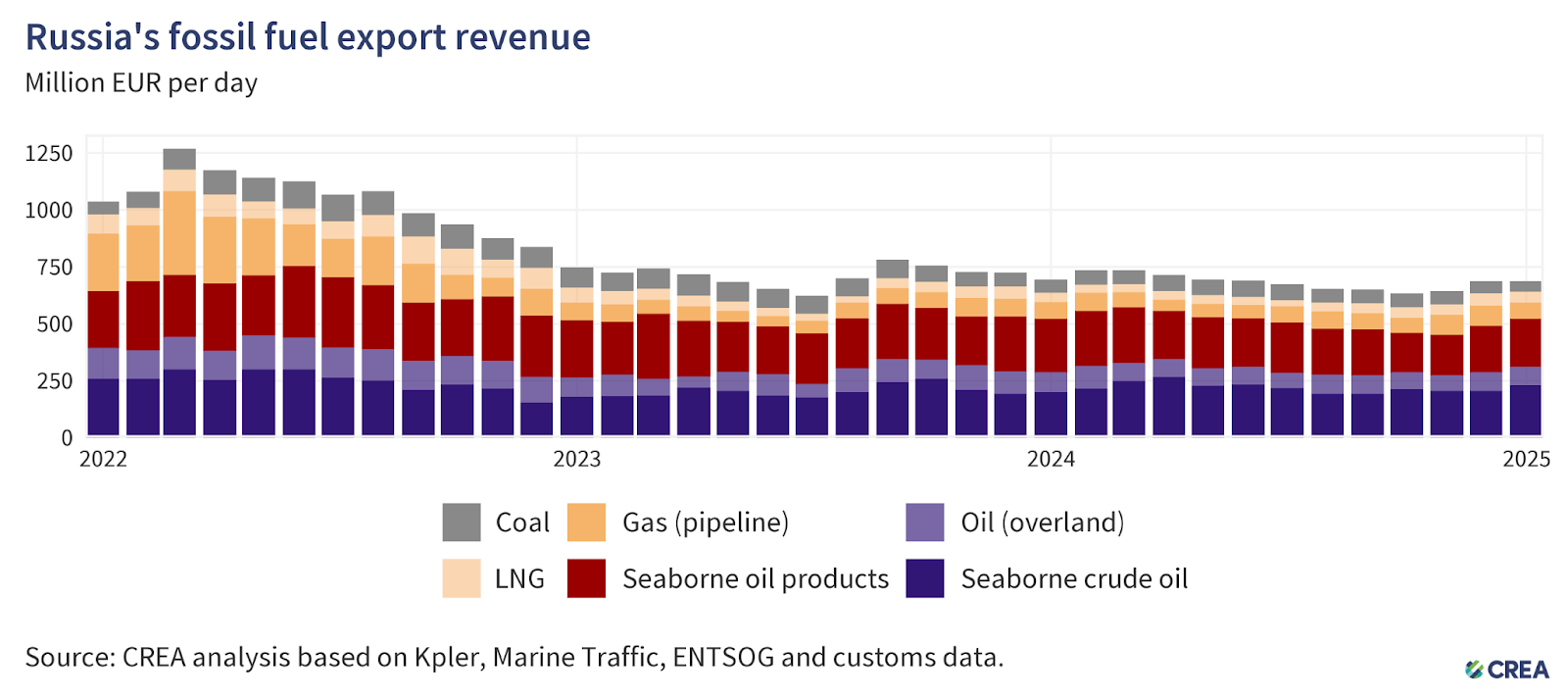

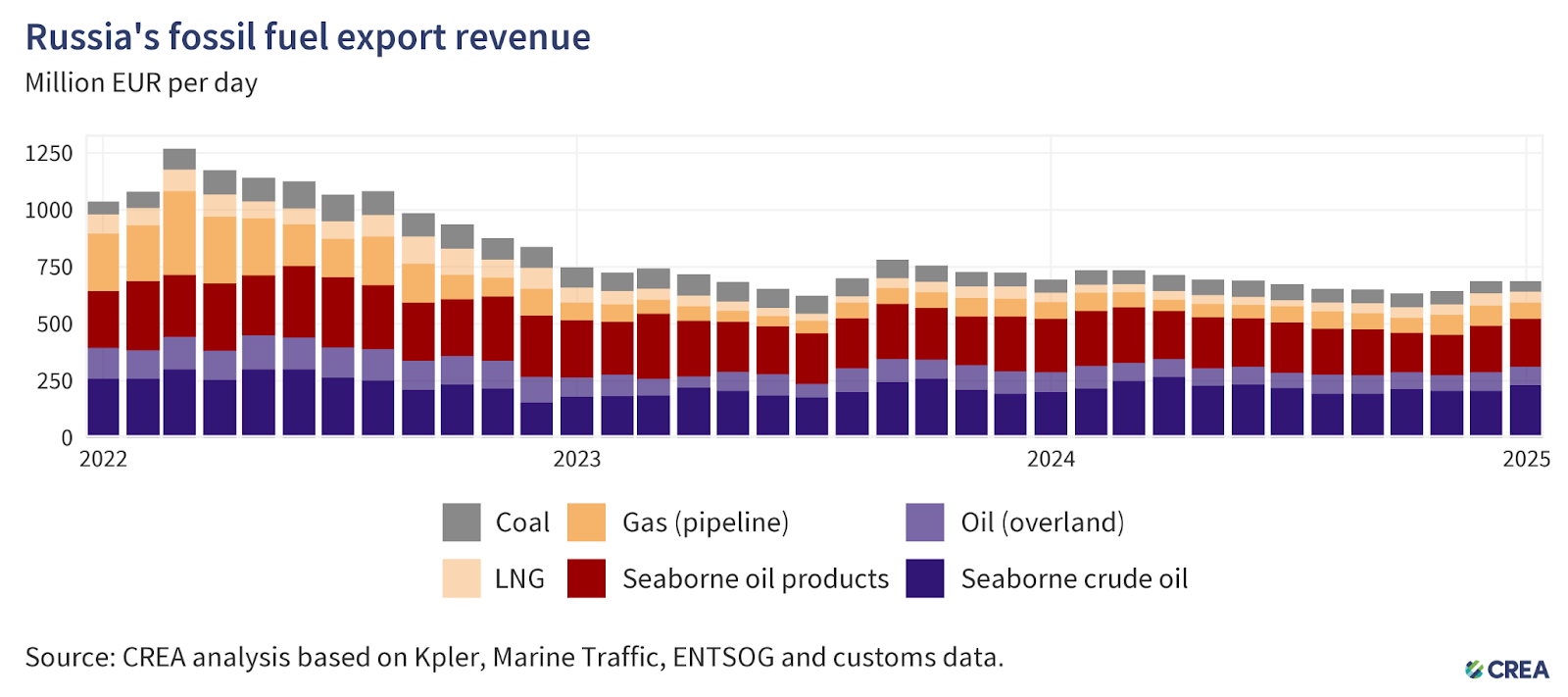

In January, Russia’s monthly fossil fuel export revenues remained unchanged month-on-month, stabilising at EUR 687 mn per day.

Revenues from seaborne crude oil surged by 13% month-on-month to EUR 231 mn per day despite a mere 2% rise in export volumes.

Russian revenues from exports to Turkey rose by 18% month-on-month — facilitated by a massive 34% surge in imports of oil products. In anticipation of a reduction in Russia’s crude exports due to vessel sanctions targeting mostly crude oil tankers, there has been a surge in oil refining in Russia aimed towards increasing global exports.

In January, France’s imports of Russian LNG saw a 25% month-on-month rise, even as the country’s total imports grew by a mere 0.5%. Over a third of France’s total LNG imports in January came from Russia and were the highest import volumes in 12 months.

‘Shadow’ tankers transported 84% of the total volume of Russian seaborne crude oil in January.

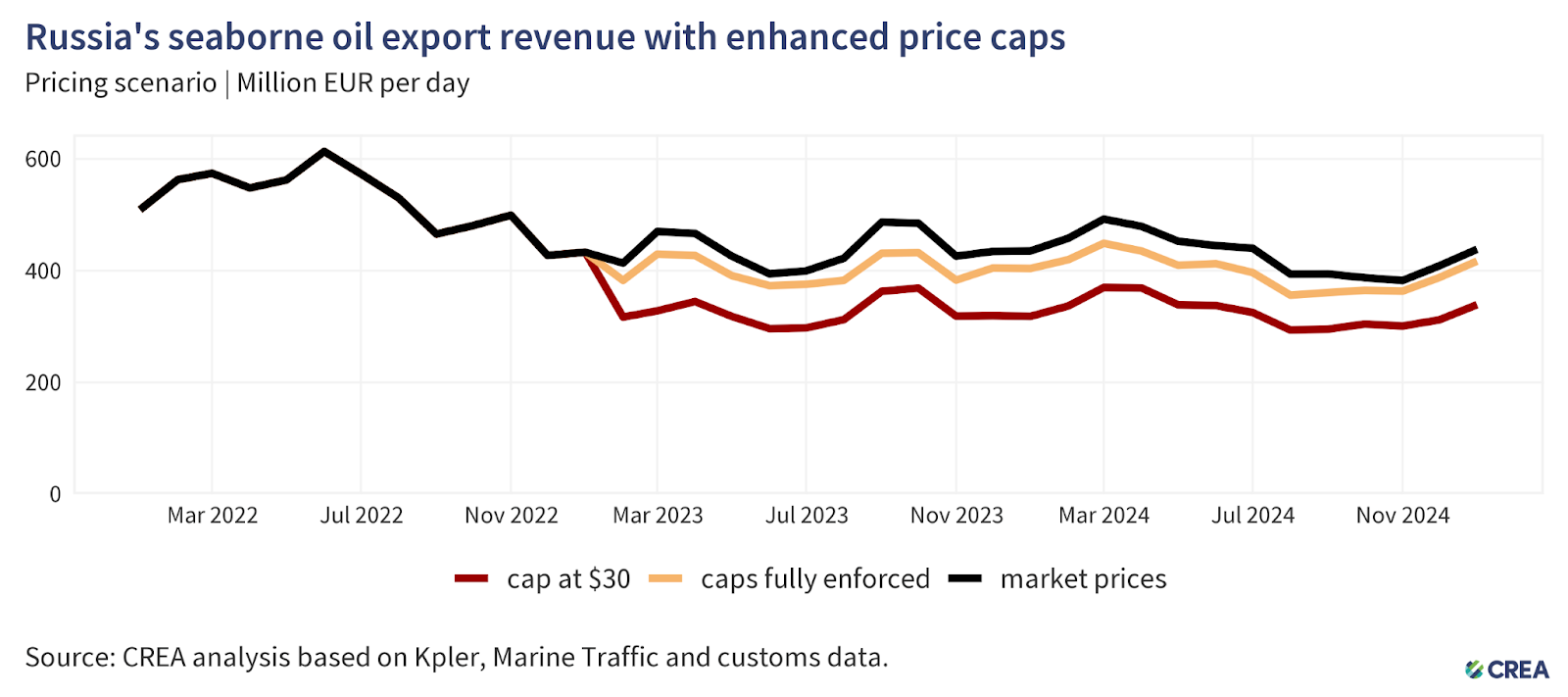

A lower price cap of USD 30 per barrel would have slashed Russia’s oil export revenue by 24% (EUR 79 bn) from the start of the sanctions in December 2022 until the end of January 2025. In January alone, a USD 30 per barrel price cap would have slashed Russian revenues by 23%.

In January, Russia’s monthly fossil fuel export revenues remained unchanged month-on-month, stabilising at EUR 687 mn per day.

Revenues from seaborne crude oil surged by 13% month-on-month to EUR 231 mn per day, despite a mere 2% rise in export volumes.

Revenues from crude oil via pipeline saw no change in January at EUR 82 mn per day.

There was a 14% surge in Russian revenues from LNG to EUR 47 mn per day in January, and volumes dropped by a similar 13%, to their lowest levels since winter set in the Northern Hemisphere.

As expected, due to the end of transit through Ukraine, Russian revenues from pipeline gas dropped by 18% in January. Volumes of pipeline gas exports also dropped by 14% in January. The transit deal expired at the end of 2024 and earned Russia EUR 5.8 bn in pipeline gas exports to the EU in 2024.

Despite a 6% reduction in export volumes, there was a 2% month-on-month rise in Russian revenues from seaborne oil products, to EUR 207 mn per day.

Russian revenues from coal exports continued to slide, dropping by 10% month-on-month to an all-time low of EUR 47 mn per day.

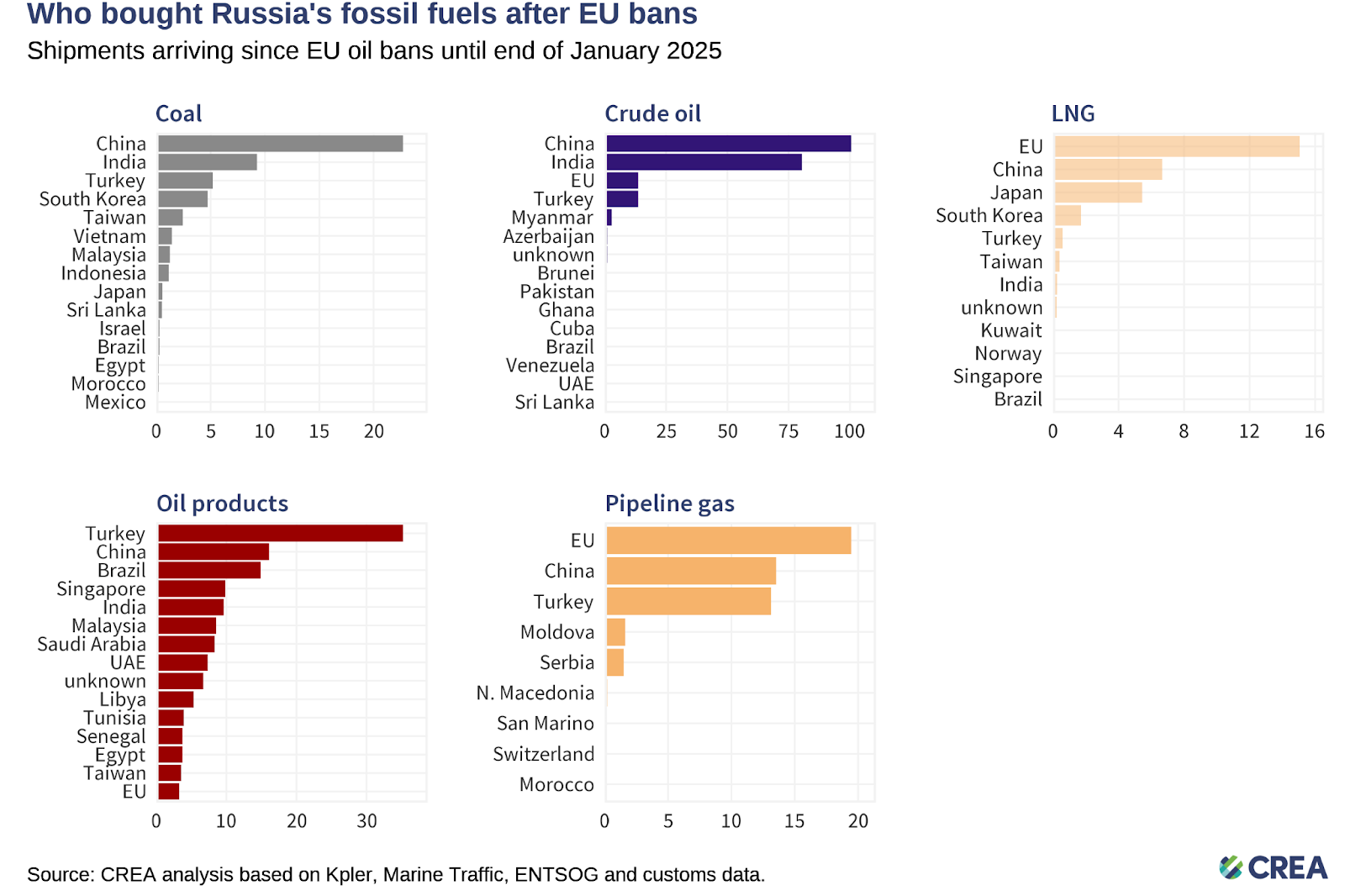

Coal: From 5 December 2022 until the end of January 2025, China purchased 45% of all Russia’s coal exports. India (18%), Turkey (10%), South Korea (9%), and Taiwan (5%) round off the top five buyers list.

Crude oil: China has bought 47% of Russia’s crude exports, followed by India (37%), the EU (6%), and Turkey (6%).

Oil products: Turkey, the largest buyer, has purchased 25% of Russia’s oil product exports, followed by China (11%), and Brazil (11%).

LNG: The EU was the largest buyer, purchasing 49% of Russia’s LNG exports, followed by China (22%), and Japan (18%).

Pipeline gas: The EU was the largest buyer, purchasing 39% of Russia’s pipeline gas, followed by China (27%), and Turkey (27%).

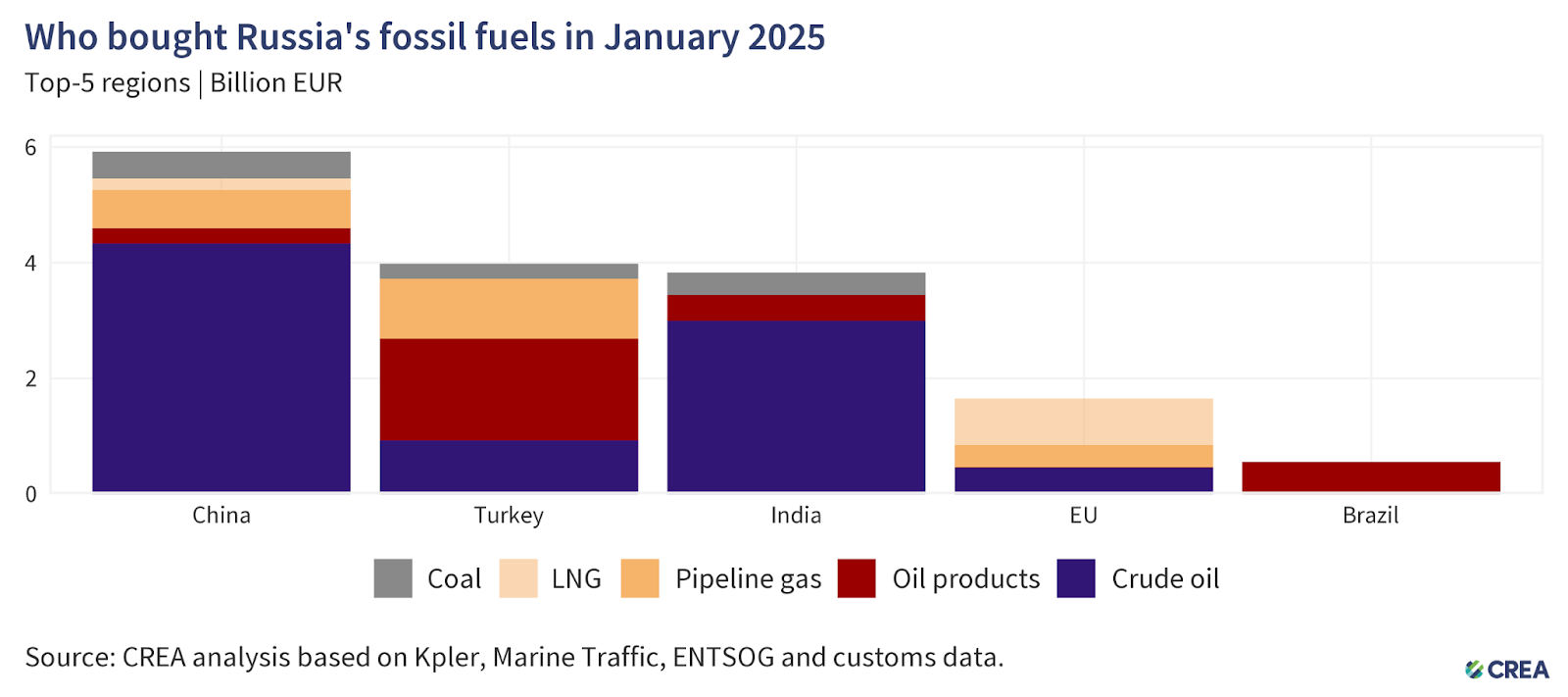

China remained the largest buyer of Russian fossil fuels in January. Their imports account for over one third (EUR 5.9 bn) of Russia’s monthly export earnings from the top five importers. Crude oil comprised 73% (EUR 4.3 bn) of China’s imports from Russia. There was an 8% month-on-month rise in China’s imports of Russian fossil fuels in January, chiefly due to a 16% increase in imports of crude oil.

Despite the rise in Russian revenues from crude exports to China, export volumes saw an 18% month-on-month drop. In January, OFAC issued sanctions on as many as 183 vessels, effectively targeting one third of its ‘shadow’ fleet. The sanctions allow for a winding down period to deliver oil as buyers seek alternatives. The sanctions have seen a rise in the spot price of (Eastern Siberia-Pacific Ocean) ESPO blend deliveries to China, due to rising freight prices.

Turkey remained the second-highest importer of fossil fuels from Russia for a third straight month, contributing 25% (EUR 3.9 bn) to Russia’s monthly export earnings from its top five importers. Turkey’s imports rose by 18% month-on-month — facilitated by a massive 34% surge in imports of oil products. Vessel sanctions are expected to bite Russian crude exports. In anticipation, there has been a surge in oil refining as Russia targets exporting refined fuels globally. Turkey has been a primary destination and imported EUR 1.7 bn of Russian refined oil products in January.

India was the third highest buyer of Russian fossil fuels in January, importing EUR 3.8 bn of Russian fossil fuels. There was a 22% month-on-month rise in India’s crude imports from Russia, which totalled EUR 3 bn. This coincided with a 13% rise in import volumes. India’s imports of Russian crude are widely predicted to drop after OFAC sanctions on vessels, with many refineries already looking to diversify supply from the Middle East. State-owned banks have also blocked payments for Russian crude after the sanctions while state-owned refineries have pulled back on talks for a long-term deal for Russian crude.

The EU was the fourth largest buyer of Russian fossil fuels in January, with their imports accounting for 10% (EUR 1.6 bn) of the top five purchasers. Almost half of these imports consisted of Russian LNG valued at EUR 796 mn.

Brazil bought EUR 560 mn of Russian fossil fuels in January, which consisted entirely of oil products.

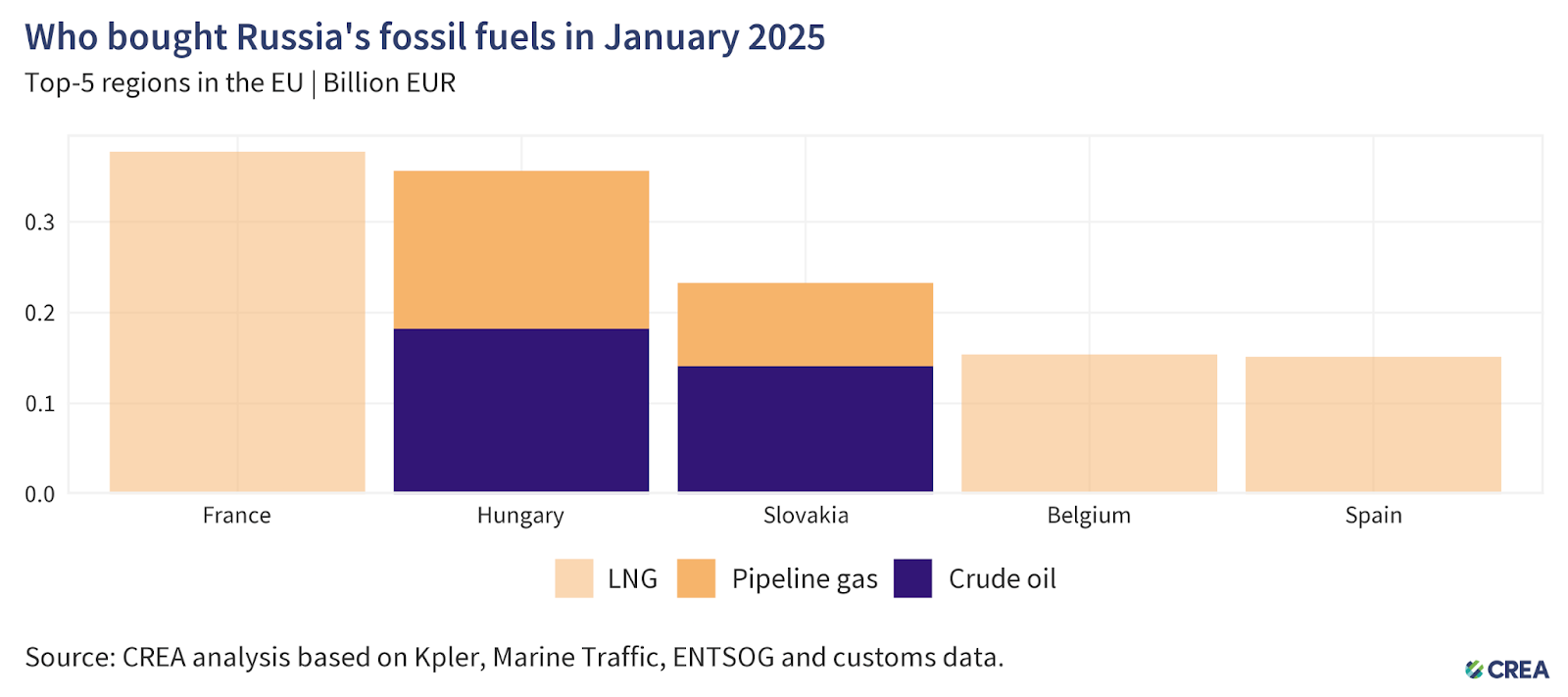

In January, the five largest Russian fossil fuel importing countries in the EU paid Russia a total of EUR 1.2 bn for their imports, over half of which were purchases of LNG. The EU has granted an exemption for Russian crude oil imported through the southern branch of the Druzhba pipeline to Hungary, Slovakia, and the Czech Republic. While Russian pipeline gas and LNG remain unsanctioned, the pipeline transit through Ukraine ended in December 2024, thereby ending Gazprom’s gas deliveries to Slovakia as well as to Czechia and Austria.

In January, France was the largest importer of Russian fossil fuels within the EU. The entirety of their imports consisted of Russian LNG totalling EUR 377 mn. In January, France’s total LNG imports rose by a marginal 0.5%. At the same time, imports from Russia saw a 25% month-on-month rise to their highest levels since January 2024. Over one third of France’s total LNG imports in January came from Russia.

The second-highest importer was Hungary, with imports totalling EUR 356 mn. Hungary’s imports consisted of crude oil (EUR 182 mn) and gas via pipeline (EUR 173 mn).

Slovakia, the third-largest buyer within the EU, imported Russian fossil fuels worth EUR 232 mn in January. Over 60% of Slovakia’s imports were Russian crude via pipeline valued at EUR 141 mn. Much of this Russian crude is refined into oil products and reexported to Czechia. This can continue because Slovakia’s exemption from the ban on exporting oil products made from Russian crude, which ended in December 2024, has been extended until June 2025.

The entirety of Belgium and Spain’s imports of Russian fossil fuels in January comprised Russian LNG worth EUR 154 mn and EUR 151 mn, respectively.

How are oil prices changing?

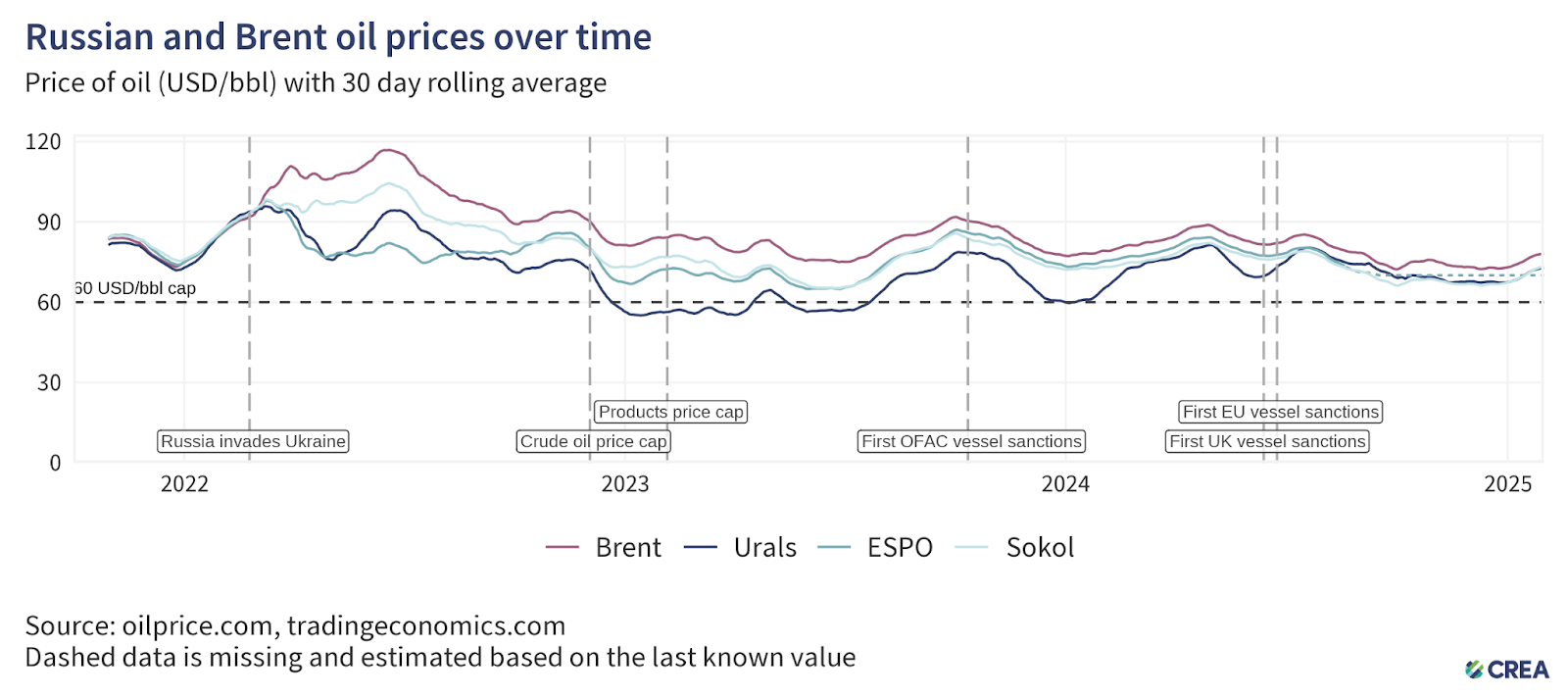

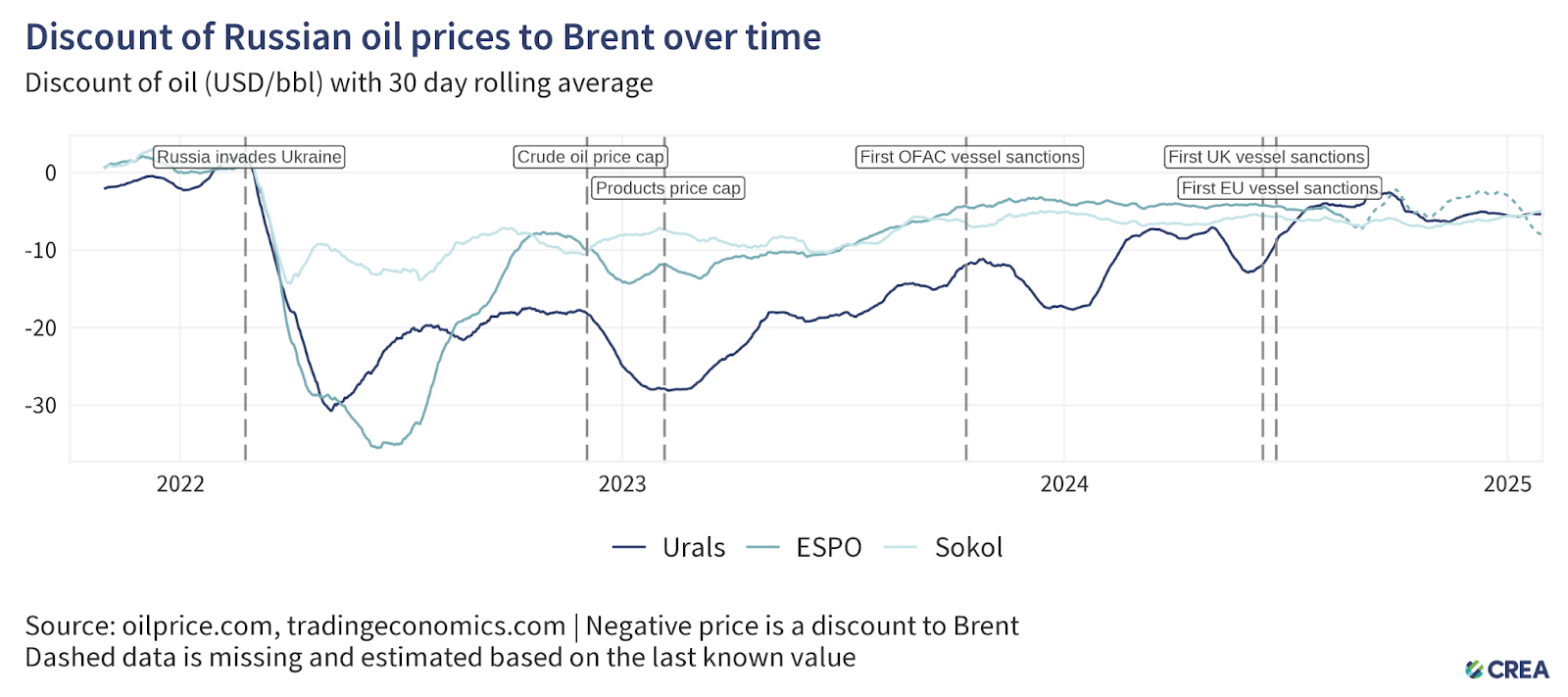

In January, the average Urals spot price saw a 4% rise, and remained above the price cap, trading at USD 70.2 per barrel.

The price of ESPO grade crude remained the same at USD 70.04 per barrel, but prices of Sokol blends of Russian crude oil saw a 6% rise to USD 70.3 per barrel. Both these grades are primarily associated with sales to Asian markets.

In January, the discount on Urals-grade crude oil saw a 4% month-on-month increase to an average of USD 5.4 per barrel compared to Brent crude oil.

The discount on the ESPO grade increased by a massive 112% to an average of USD 5.69 per barrel, while the discount on the Sokol blend narrowed by 11% to USD 5.39 per barrel.

Throughout this period, vessels owned or insured by G7+ countries1 continued to load Russian oil in all Russian port regions where average exported crude oil prices remained above the price cap level. These cases call for further investigation by enforcement agencies for breaches of sanctions.

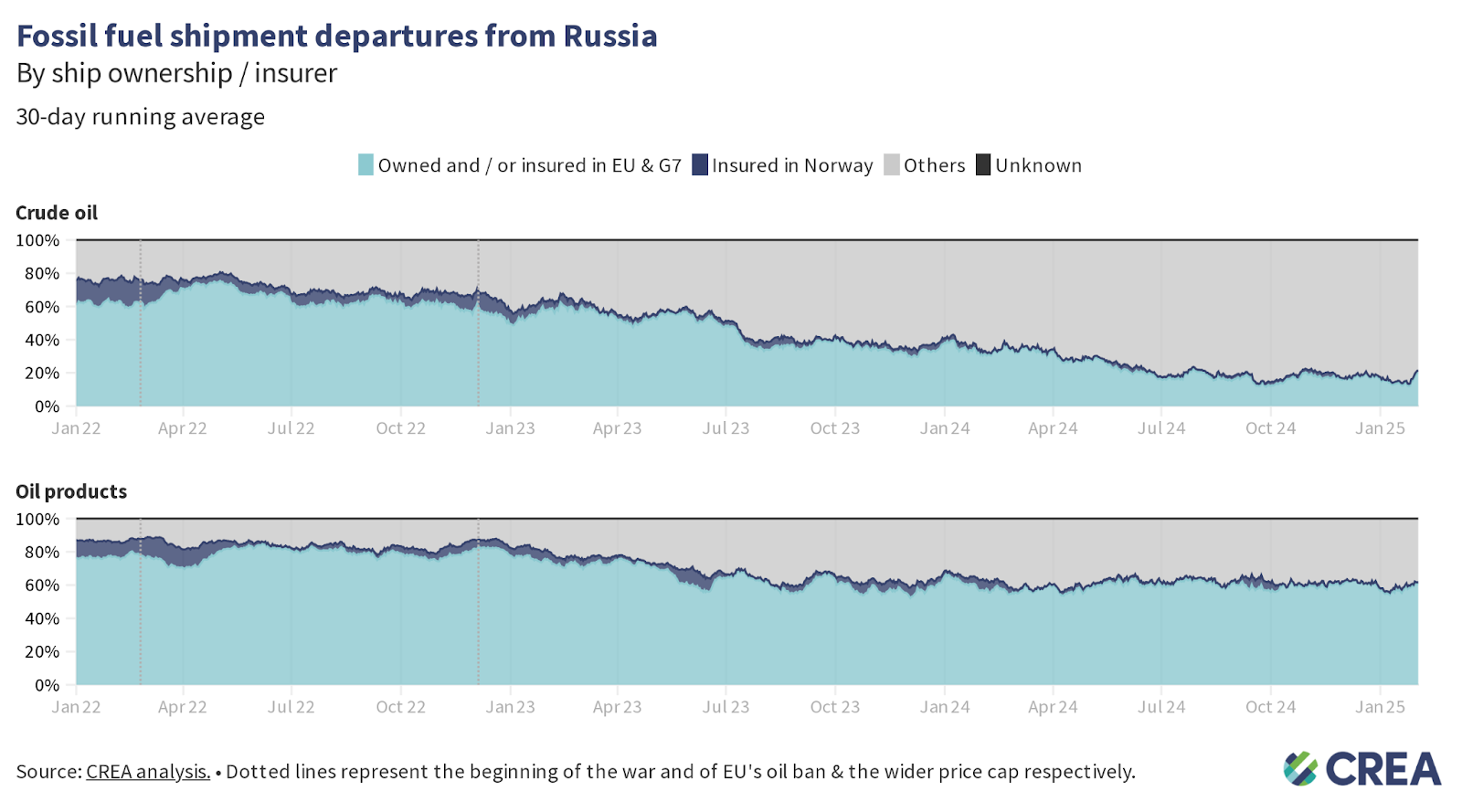

In January, 66% of Russian seaborne crude oil and its products were transported by ‘shadow’ tankers and not subject to compliance with the oil price cap policy. The remainder was transported by tankers subject to the oil price cap.

‘Shadow’ tankers transported 84% of the total volume of Russian seaborne crude oil, while tankers owned or insured in countries implementing the price cap accounted for 16% of the total volume of Russian crude exported in January.

‘Shadow’ tankers transporting oil products handled 41% of Russia’s total volume of products. The remaining volume was shipped by tankers subject to the price cap policy.

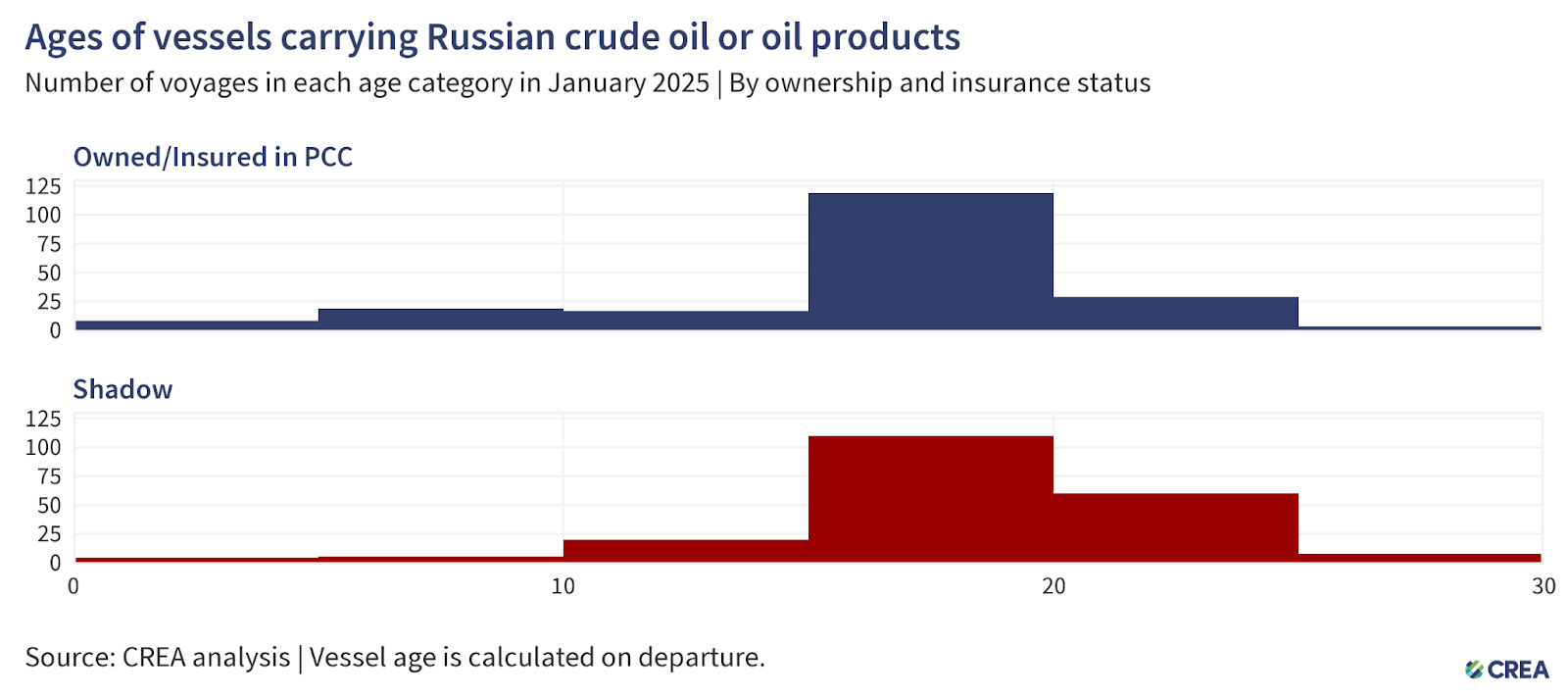

In January, 402 vessels exported Russian crude oil and oil products, of which 207 were ‘shadow’ tankers. One third of these ‘shadow’ tankers were at least 20 years old or older. The oldest tanker transporting Russian oil in January was 33 years old.

Older ‘shadow’ tankers transporting Russian oil and petroleum products across EU Member States’ exclusive economic zones, territorial waters, or maritime straits raise environmental and financial concerns due to their age, questionable maintenance records, and insurance coverage. Their insurance potentially lacks sufficient protection & indemnity (P&I) coverage to cover the cost in the event of an oil spill or catastrophe. In the case of accidents, coastal countries may bear the financial brunt of the cleanup, not to mention the repercussions of damage to their marine ecology.

The cost of cleanup and compensation resulting from an oil spill from tankers with dubious insurance could amount to over EUR 1 bn for coastal country’s taxpayers.

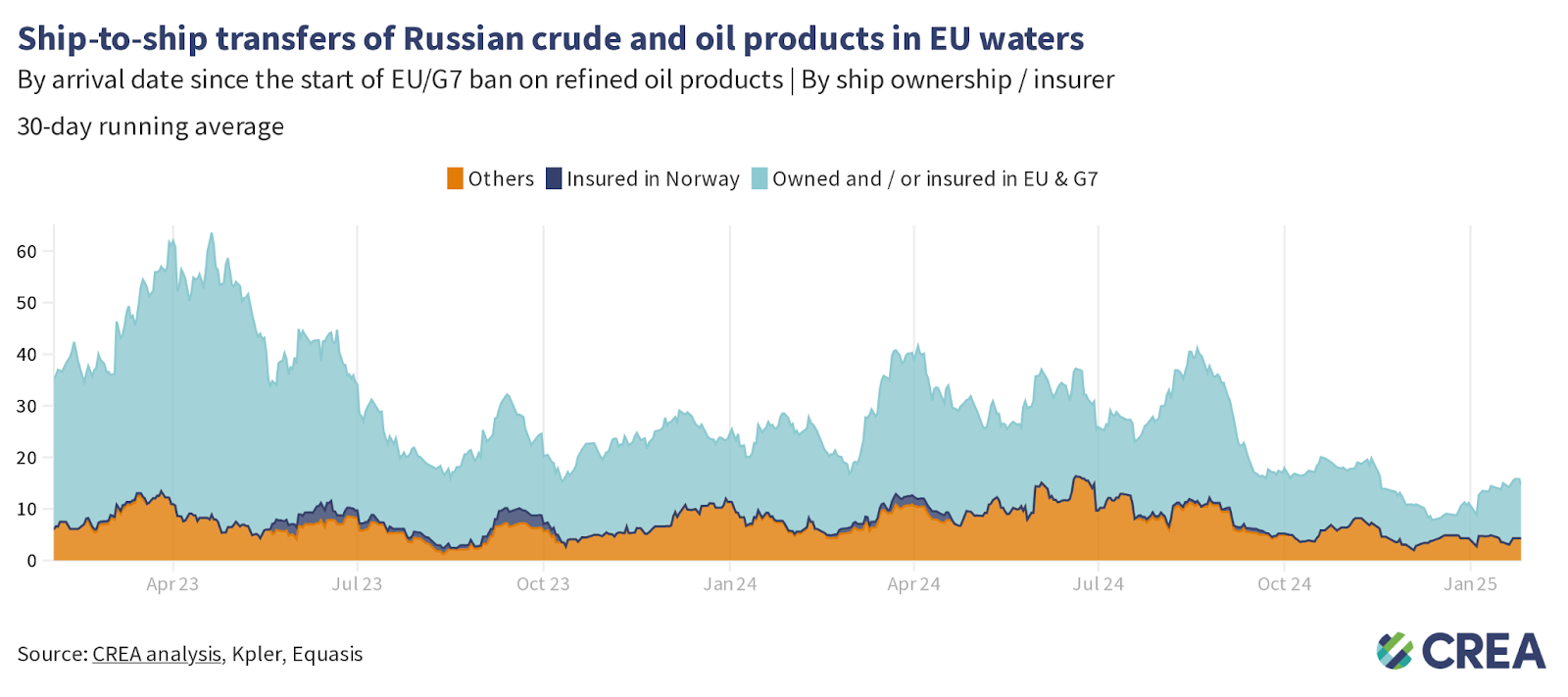

In January, Russian oil underwent ship-to-ship (STS) transfers in EU waters totalling EUR 172 mn per day.

69% of these transfers were facilitated by tankers covered by G7+ insurance. STS transfers of Russian oil severely undermine sanctions by allowing Russia to evade sanctions and price caps by splitting the cargo to multiple buyers and mixing lower-priced Russian oil with non-Russian oil.

‘Shadow’ tankers with an average age of 17 years conducted environmentally dangerous ship-to-ship transfers totaling EUR 54 mn per day in EU waters.

Russia’s fossil fuel export revenues have fallen since the sanctions were implemented, subsequently constricting Putin’s ability to fund the war. However, much more should be done to limit Russia’s export earnings and constrict the funding of the Kremlin’s war chest. This includes lowering the oil price cap, increasing monitoring and enforcement of sanctions, and banning unsanctioned fossil fuels such as LNG and pipeline fuels that are legally allowed into the EU.

Lowering the oil price cap

A lower price cap of USD 30 per barrel (still well above Russia’s production cost, which averages USD 15 per barrel) would have slashed Russia’s oil export revenue by 24% (EUR 79 bn) from the start of the sanctions in December 2022 until the end of January 2025. In January alone, a USD 30 per barrel price cap would have slashed Russian revenues by 23% (EUR 3.08 bn).

Lowering the price cap would be deflationary, reducing Russia’s oil export prices and inducing more production from Russia to make up for the drop in revenue.

Since introducing sanctions until the end of January 2025, thorough enforcement of the price cap would have cut Russia’s export revenues by 8% (EUR 25.66 bn). In January 2025 alone, full enforcement of the price cap would have reduced revenues by 5% (approximately EUR 0.66 bn).

Restrict the growth of ‘shadow’ tankers & plug the refining loophole

Russia’s reliance on tankers owned or insured in G7+ countries has fallen due to the growth of ‘shadow’ tankers. This subsequently impacts the coalition’s leverage to lower the price cap and hit Russia’s oil export revenues. Sanctioning countries must prevent Russia’s growth in ‘shadow’ tankers that are immune to the oil price cap policy.

G7+ countries must also plug the widening refining loophole by banning the importation of oil products produced from Russian crude oil. This would enhance the impact of the sanctions by disincentivising third countries from importing large amounts of Russian crude and helping cut Russian export revenues. Banning the imports of oil products from refineries that process Russian crude oil would also lower the price of Russian oil, as they would struggle to find buyers or expand their market.

Stronger enforcement & monitoring

Enforcement agencies overseeing the sanctions must take proactive measures against violating entities, including insurers registered in price cap coalition countries, shippers, and vessel owners.

Despite clear evidence of violations, agencies must do more to enforce penalties against shippers, insurers, or vessel owners. This information must be shared widely in the public domain. Penalties against violating entities increase the perceived risk of being caught and serve as a deterrent.

Penalties for violating the price cap must be significantly harsher. Current penalties include a 90-day ban on vessels from securing maritime services after violating the price cap, a mere slap on the wrist. If found guilty of violating sanctions, vessels should be fined and banned in perpetuity.

Sanctions enforcement bodies must continue to sanction ‘shadow’ tankers as doing so hinders Russia’s ability to transport its oil above the price cap. CREA estimates that the Office of Foreign Assets Control (OFAC)’s initial sanctioning of ‘shadow’ tankers widened the discount that Russia offered buyers of its oil and cut Russia’s crude oil export revenues by 5% (EUR 512 mn per month).

The lack of proper monitoring and enforcement along with rising oil prices have increased Russia’s export revenues to fund its war against Ukraine.

The G7+ countries should ban STS transfers of Russian oil in G7+ waters. STS transfers undertaken by old ‘shadow’ tankers with questionable maintenance records and insurance pose environmental and financial risks to coastal states and support Russia in logistically exporting high volumes of crude oil. Coastal states should require ‘shadow’ tankers transporting Russian oil through their territorial waters to provide documentation showing adequate maritime insurance. If ‘shadow’ tankers fail to do so, they should be added to the OFAC, UK, and European sanctions list. This policy could limit Russia’s ability to transport its oil on ‘shadow’ tankers, exempt from complying with the oil price cap policy.

Relevant reports:

Note on methodology:

Update 2023-10-19 – We now use Kpler to estimate seaborne exports from Russia and other countries. This change increases our tracker’s estimate of exports from Russia to the world by EUR 77.8 bn (+18% increase) and the exports to the EU by EUR 12.4 bn (+2.8% increase).

We have also changed how we receive protection and indemnity (P&I) insurance information about ships to obtain data directly from known P&I providers and Equasis. This ensures we have recorded the correct start date for a ship’s insurance.

Find out more details on the changes in our methodology, which are explained in our article about the migration from automatic identification system (AIS) data providers to the Kpler dataset.

The data used for this monthly report is taken as a snapshot at the end of each month. The data provider revises and verifies data on trades and oil shipments throughout the month. We subsequently update this verified data each month to ensure accuracy. This might mean that figures for the previous month change in our updated subsequent monthly reports. For consistency, we do not amend the previous month’s report; instead, we treat the latest one as the most accurate data for revenues and volumes.

Calculating the impact of sanctions: We estimated the impact of the EU/G7 crude oil ban and price cap by estimating the price of Urals in the absence of the cap and Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. We do this by first calculating the average difference between the spot prices of Brent and Urals in the year before the invasion. This average difference is used to estimate an expected price of Urals based on the current value of Brent since the start of the price cap. We use this expected price of Urals and the current price of Urals, along with the volumes of Urals traded from Kpler, to estimate the difference in the total value of Russia’s exports.