Miso, the beloved Japanese paste made by fermenting cooked soybeans and salt, is known for its rich umami flavor and versatility in the kitchen. But what happens when you take this centuries-old culinary tradition and send it into orbit?

That’s the question a team of researchers sought to answer in a new study published in the journal iScience. Their goal? To test whether fermentation, a process driven by live microbes, could succeed in the harsh environment of space—and whether the resulting food would still be edible or even enjoyable.

“There are some features of the space environment in low Earth orbit—in particular microgravity and increased radiation—that could have impacts on how microbes grow and metabolize and thus how fermentation works,” co-lead author Joshua D. Evans of the Technical University of Denmark said in a recent statement. “We wanted to explore the effects of these conditions.”

Making Miso on the ISS

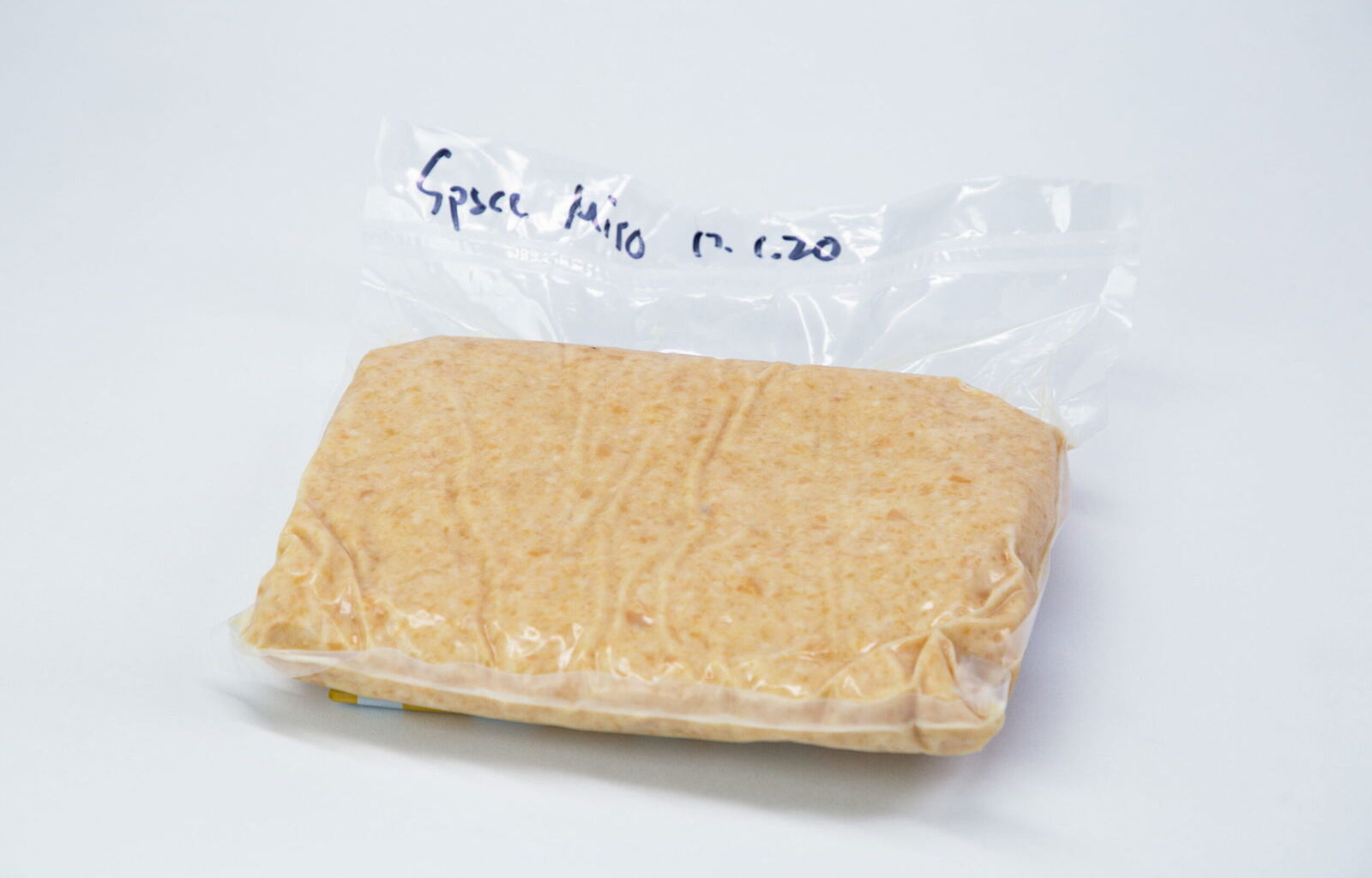

In March 2020, the team sent a small container of “miso-to-be” to the International Space Station (ISS), where it remained for 30 days to ferment. Two identical batches were kept on Earth—one in Cambridge, Massachusetts, and one in Copenhagen, Denmark—as controls. To closely monitor the process, each batch was housed in a specially designed box that tracked temperature, humidity, pressure, and radiation levels.

After the ISS miso returned to Earth, researchers analyzed its microbial communities, amino acid composition, and, of course, flavor. They found that despite the challenges of space, the miso fermented successfully. Interestingly, the bacterial makeup of the space miso differed from its Earth-bound counterparts, likely due to the effects of microgravity and radiation.

“Fermentation [on the ISS] illustrates how a living system at the microbial scale can thrive through the diversity of its microbial community, emphasizing the potential for life to exist in space,” co-lead author Maggie Coblentz of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology noted. “While the ISS is often seen as a sterile environment, our research shows that microbes and non-human life have agency in space.”

As for the taste, researchers reported that all three samples had the classic salty, umami-rich profile expected from miso. But the ISS miso stood out with a slightly more roasted, nutty flavor—an intriguing variation that may reflect its time in orbit.

Miso in Space: Flavor, Well-Being, and Equity

Beyond proving that miso can ferment in microgravity, the study opens doors to new possibilities in space food systems. For astronauts on long-duration missions, fermented foods like miso could offer not just nutrition but comfort, variety, and a connection to Earthly traditions.

“By bringing together microbiology, flavor chemistry, sensory science, and larger social and cultural considerations, our study opens up new directions to explore how life changes when it travels to new environments like space,” Evans said. “It could enhance astronaut well-being and performance, especially on future long-term space missions.”

However, the researchers also see broader meaning in the work. Coblentz pointed out that using food as a scientific and cultural tool can spark meaningful conversations about who participates in space exploration—and how we design systems that reflect diverse human experiences.

“We’ve used something as fundamental as food as a starting point to spark conversations about social structures in space and the value of domestic roles within scientific and engineering fields,” said Coblentz. “The way we design systems in space sends a powerful message about who belongs there, who is invited, and how those people will experience space.”

In other words, a jar of space-fermented miso may be small, but it carries significant implications for the future of food, science, and humanity among the stars.

Kenna Hughes-Castleberry is a freelance science journalist and staff writer at The Debrief. Follow and connect with her on BlueSky or contact her via email at kenna@thedebrief.org