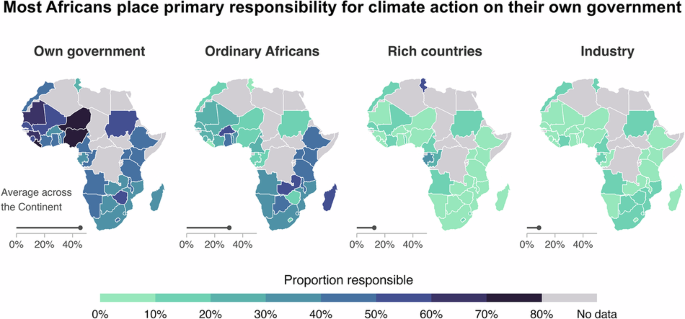

Almost half (45%) of Africans who have heard of climate change, believe their own government is primarily responsible for addressing climate change and reducing its impacts. By comparison, 30% attribute primary responsibility to everyday Africans themselves. Historic emitters are least often selected, including rich countries (13%) and business and industry (8%). Respondents most likely to have heard of climate change include men, those with higher levels of formal education, increased news access, resources, community engagement, and drought perceptions, replicating existing work identifying the determinants of climate change literacy on the African continent16,30 (Supplementary Table 1).

Figure 1 shows the variation in who citizens say is primarily responsible for climate action. West African citizens stand out with the highest proportion of views that their own governments are responsible for climate change (Nigeria, Liberia, Niger, The Gambia, Guinea, Mauritania, Sierra Leone, Mali and Senegal; >50%). For example in Nigeria, 76% of respondents in Africa’s most populous country that have heard of climate change assign primary responsibility for addressing climate change to their government and other analysis of this data have shown 71% want the Nigerian government to take immediate action to limit climate change, even if it is expensive, causes job losses, or takes a toll on the economy31.

a Comparison of proportion of respondents in each country who have heard of climate change and believe the actor most responsible for limiting climate change is their own government, ordinary Africans, rich countries, or industry. b Per country proportions for all response options among those that have heard of climate change. ‘Traditional leaders’ and ‘someone else’ were combined to a single “Other” category.

Some countries like Uganda, Benin, Ethiopia, Ghana and Kenya show a relatively even split in primary responsibility placed on government and ordinary people. Yet there is a range of countries from all regions, and across low- to middle-income countries, where responsibility is primarily attributed to individuals (Madagascar, Burkina Faso, Zambia, Botswana, Tanzania, Kenya; >45%). These findings are consistent with other global surveys that show the majority of respondents in 42 countries think that individual people are the most responsible for reducing causes of climate change, including 8 from sub-Saharan Africa (Ghana, Benin, Burkina Faso, Zambia, Botswana, Malawi, Kenya and Tanzania)9.

Among the top ten countries in which citizens attribute primary responsibility to historic emitters are all four small island states (Cabo Verde, Mauritius, Seychelles, and Sao Tome & Principe). This may reflect an awareness that these populations face growing risk of sea level rise. Malawi and Zimbabwe stand out as the two countries where a significant number of respondents (9%) attribute responsibility to traditional leaders highlighting the particular importance of including Indigenous knowledge holders in climate action in such countries. In Supplementary Table 16, we present the joint descriptive statistics for the proportion who have heard of climate change and proportion who attribute responsibility to each actor for each country.

Individual Differences: The role of resources, education and information

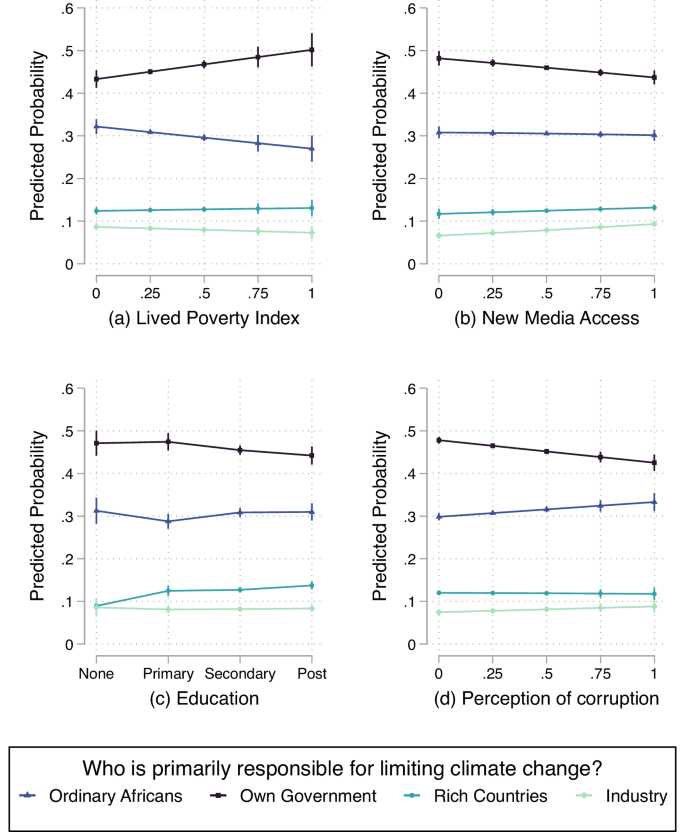

This analysis focuses on the attitudes of citizens who are aware of climate change. Using a multinomial logistic regression approach (see Methods), it first identifies the relationship between resources and information on the attribution of responsibility. Africans who have access to material resources are more likely to attribute responsibility for climate action to their fellow citizens. Those who score lowest on the lived poverty index (i.e., low levels of material deprivation) are 5.20 percentage points more likely to attribute responsibility to ordinary Africans compared to the other entities (p = 0.04; Fig. 2). It also aligns with global assessments of observed human responses to climate change that show household and community level actors are the most frequently documented responders to climate change in Africa28. The results also extend those of other studies that show those more vulnerable to climate change are more willing to act5.

Those with secondary or post-secondary education are significantly more likely to attribute responsibility to rich countries (secondary: 3.80 percentage points, post-secondary: 4.90 percentage points, both p’s p = 0.006) toward business and industry (2.85 percentage points, p 3 – 6).

Respondents were also asked whether they believe everyday Africans can do something to stop climate change, as well as whether the government should do something to stop climate change. Lower levels of poverty, higher levels of education, and more frequent access to new media are associated with both belief Africans can and their government should do more to address climate change (Supplementary Table 7). In conjunction with the findings on attribution of responsibility, these results suggest that resources and information are associated with support for climate action broadly, increased confidence that everyday Africans can act, and recognition that historic emitters should play a larger role in such action. That is, increased resources and information may increase an overall sense of responsibility to address climate change while shifting priorities of who should act.

Other socio-demographic characteristics have little to no relationship with attribution of responsibility for addressing climate change to different actors (Supplementary Table 2). This includes other markers of vulnerability associated with increased climate change literacy, such as community engagement, access to traditional news sources like radio and newspapers, and gender.

Responsibility attribution and the role of government

Most Africans attribute primary responsibility for climate action to their own government. Yet, state capacity and citizens’ perceptions of government performance vary widely across the continent, which has the potential to influence responsibility attributed to the government.

Starting with individuals’ perception of corruption, those who believe their government is corrupt are less likely to attribute responsibility for addressing climate change to their government (5.24 percentage points, p 2), and instead place more responsibility on citizens. Perceived corruption is therefore associated with lower expectations of government to engage in climate action. This effect remains statistically significant even after controlling for respondents’ party identification (close to ruling party), and their evaluation of elected officials’ responsiveness to citizen concerns (Supplementary Tables 10 and 11).

To more precisely identify the relationship between attribution of responsibility and state functioning, we turn to measures of state professionalism. Professionalism measures whether a range of services are easy to use and free from corruption. They are important because they are enablers of climate action and human development more broadly (e.g., education, health care, and municipal services)13. The professionalism measure used here aggregates individual reports about ease of service access and freedom from corruption to the regional level and these analyses include a control variable for the geographic reach of the state. Given the significant variation of state infrastructure across these types of services in Africa, as well as low- and middle-income countries more broadly32,33, controlling for state infrastructure helps to isolate the effect of professionalism on climate action. These measures have been previously validated (see Methods)34.

State professionalism has a significant and positive association with responsibility attributed to citizens and decrease in perception that their government is responsible (both p’s 35,36,37,38,39,40. It is also important to note that while the state may be present in the region, for example by providing schools and hospitals, that does not necessarily mean those public resources are run well. And indeed, the mere presence of the state does not associate with increased responsibility attributed to ordinary Africans nor the state government (see Supplementary Table 15 and Supplementary Fig. 1 for additional results).

State capacity and climate action: a virtuous cycle?

The results above suggest that state professionalism may encourage citizens to take climate action. This has the potential to create a virtuous cycle in which a capable state enables citizen action and political accountability41,42, which in turn further increases governments’ incentives to provide basic and professional services43. While relying on cross-sectional data limits the ability to fully test for this cycle, additional results presented here are consistent with the hypothesized dynamic.

For state professionalism to encourage citizens to engage in climate action, it should be associated with increased citizens perception that everyday Africans can do something to address climate change. Empirical evidence supports this: in regions with high levels of state professionalism, respondents are more likely to say that ordinary citizens can do something to address climate change (0.154, p = 0.011). The relationship holds, even after controlling for other factors such as education and material wealth, which are also associated with individuals’ efficacy in the face of climate change (Supplementary Table 15).

At least two additional connections are required to establish the virtuous cycle between government professionalism and citizen action. First, citizens living in regions with higher levels of state professionalism also need to be more likely to believe that the government should do more to address climate change (even if it does not take a lead role). Second, citizens living in these parts of the country and holding these beliefs need to be more likely to hold the government accountable.

Consistent with these predictions, where state professionalism is higher, citizens are also more likely to say that their government should act now to address climate change, even if it might come at a cost (0.119, p 8,44).

They are also more likely to take action to hold the government accountable. Specifically, they are more likely to report having turned out to vote in the previous election (0.158, p = 0.26, see Supplementary Table 15). While voting is only one action citizens can take to hold their governments accountable, it is both a centrally important action and, in many instances, a costly action making it a conservative test of the virtuous cycle. We note that while political participation can be subject to social desirability biases where people feel pressure to over-report turnout, Afrobarometer’s ‘Voting turnout’ variable is the standard way of measuring turnout across regime types in Africa45,46,47,48.

It is important to reiterate that the cross-sectional nature of the data provides correlational evidence, but prohibits any causal claims. State professionalism is associated with citizens’ increased willingness to address climate change, their increased demand that the state also addresses the issue, as well as their willingness to hold the government accountable, all three are consistent with the virtuous cycle.

Future work is necessary to fully identify this cycle, as well as to determine which actors and institutions and government most affect and are affected by this interface with the public in the context of climate change (see also49). In contrast, the mere presence of public service infrastructure has no statistically significant effect on citizens’ perceptions of being able to limit climate change; and actually decreases perceptions that the state should do something to address climate change (Supplementary Table 15). This suggests that a virtuous cycle is unlikely to develop by merely expanding the reach of the state in Africa, but rather, highlights the importance of state professionalism in climate action.

Future work is also necessary to uncover the causes and consequences of the different types of action governments may take in this cycle. For example, governments can allocate resources across mitigation and adaptation, and implement both of these policies across different sections (e.g., disaster prevention, water management)50,51,52. The intersection of the growing literature on determinants of government action and public opinion has the potential to shed light on how the specific steps taken by the government change public attributions of responsibility and vice versa.

Our results are limited to the perspective of citizens who are aware of climate change. Those who are unaware will also not have an opinion about which group is most responsible for addressing the crisis. While these citizens may not hold their government accountable for failing to act on climate change, they may note that limited government resources are being diverted away from other important issues facing their country. Future work is needed to identify the joint effects of climate change literacy, the attribution of responsibility, and how the Africans evaluate the action of their governments in addressing or failing to address ongoing climate change.