GRAND FORKS — Less than four years before he was awarded the Democratic presidential nomination instead of Al Smith, Franklin D. Roosevelt wrote a letter to a fellow political insider in Grand Forks expressing his hope to see then-Gov. Smith elected president of the United States.

“Roosevelt eventually succeeded Smith as governor of New York, but there’s no doubt that he also had his eyes on the White House,” said Curt Hanson, University of North Dakota archivist.

Though some scholars say Roosevelt didn’t do everything in his power to get Smith elected in 1928 — perhaps because of an interest in the next presidential race — this letter offers a different perspective.

“Granted, it’s just one letter sent to one person in a rural state, but it shows that Roosevelt was supporting Gov. Smith,” Hanson said. “He was reaching out to another fellow Democratic Party official, trying to draw support for him.”

President Franklin D. Roosevelt signs the declaration of war against Japan after the Pearl Harbor attack.

The fellow party official who communicated with Roosevelt was Samuel Torgerson, a longtime banker who, despite never becoming a politician himself, was heavily involved in politics.

Torgerson was born in Waupaca County, Wisconsin, on June 18, 1856, according to UND Special Collections archives. His professional background prior to moving to North Dakota involved teaching and studying law. He moved to Mayville, North Dakota, in 1893, taking up a banking position at the First National Bank of Mayville.

He relocated in 1904 to Grand Forks, where he became a founding member of the Scandinavian-American Bank. He served as cashier until 1933, when he took on a role as secretary-treasurer of the National Farm Loan for Grand Forks County with the Federal Land Bank of St. Paul. He also served as president and vice president of banks in Upham and Mekinock.

“It seems clear he was a very busy guy,” Hanson said. “He had multiple financial and banking interests spread throughout the Red River Valley, even though they kind of focused on Grand Forks.”

Though he had no professional investment in politics, that may have put Torgerson in a unique position, allowing him to discuss issues with others without them questioning whether he was seeking personal political advancement.

“There’s not a lot of (personal) gain, but he’s doing it for the good of the party and the good of the country,” Hanson said.

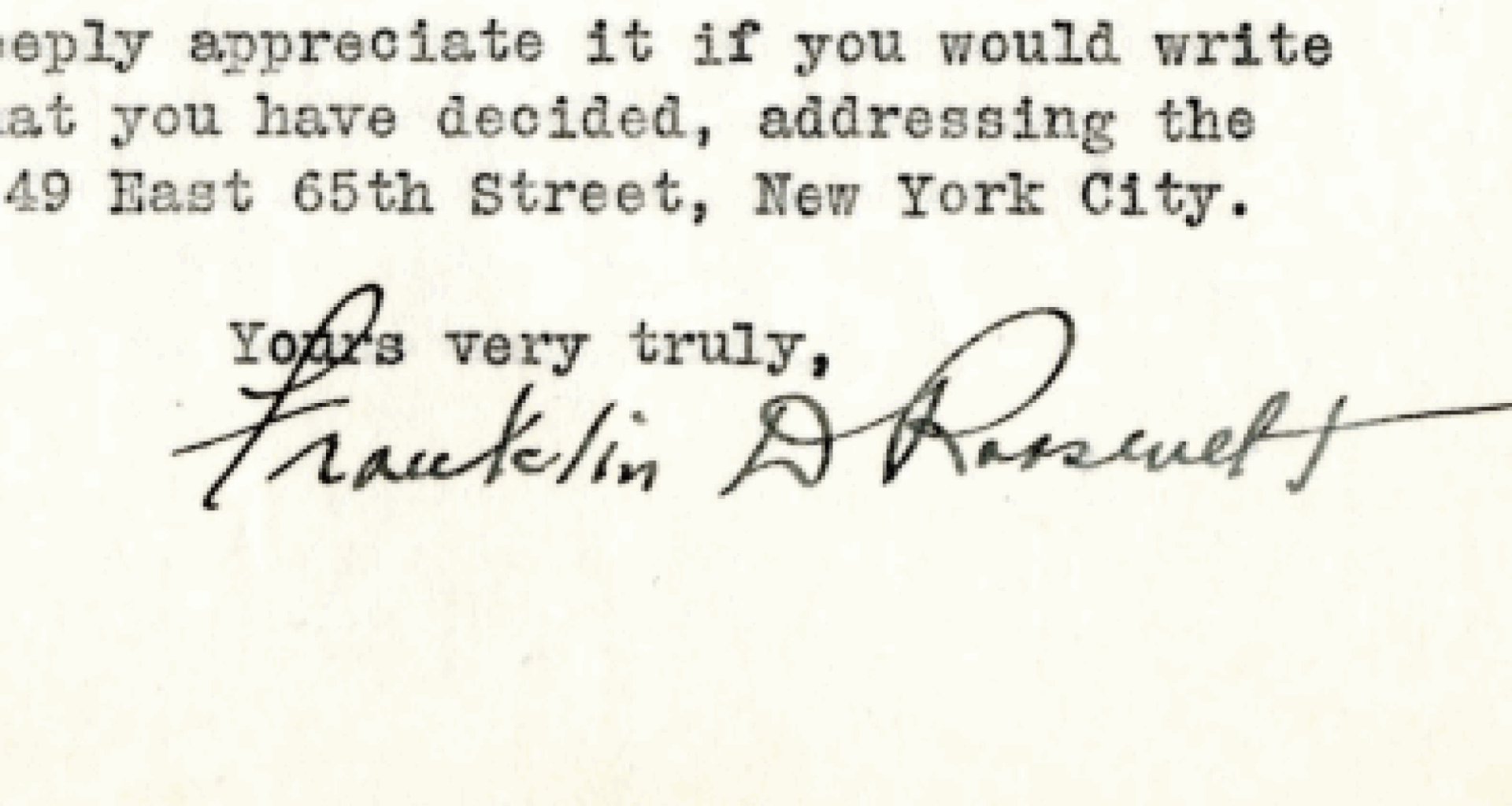

The letters exchanged between Roosevelt and Torgeson the month before the 1928 presidential election showed both men’s personal investment in the trajectory of the country.

Roosevelt’s letter, dated Oct. 13, 1928, begins with him explaining his uncertainty of Torgerson’s stance on the upcoming election. However, because of Torgerson’s previously expressed support for Woodrow Wilson — whom Roosevelt referred to as “our greatest president” — he was hopeful Torgerson would make the same conclusion he had in voting for Smith.

Roosevelt goes on to say that “materialistic and self-seeking advisers” surround the other candidate, Herbert Hoover, and they have made it clear that high ideals and forward-looking policy are very unlikely under a Hoover presidency.

“He’s alluding to the fact that the people surrounding Herbert Hoover are all in it for the money, and the prestige and the influence,” Hanson said.

It’s interesting to see a narrative like this, he said, because almost 100 years later it’s still commonplace. Perhaps the most recent, well-known example would be Elon Musk, who some speculate is involved in U.S. politics purely for his own financial gain, because of the contracts his businesses hold with the government, Hanson said.

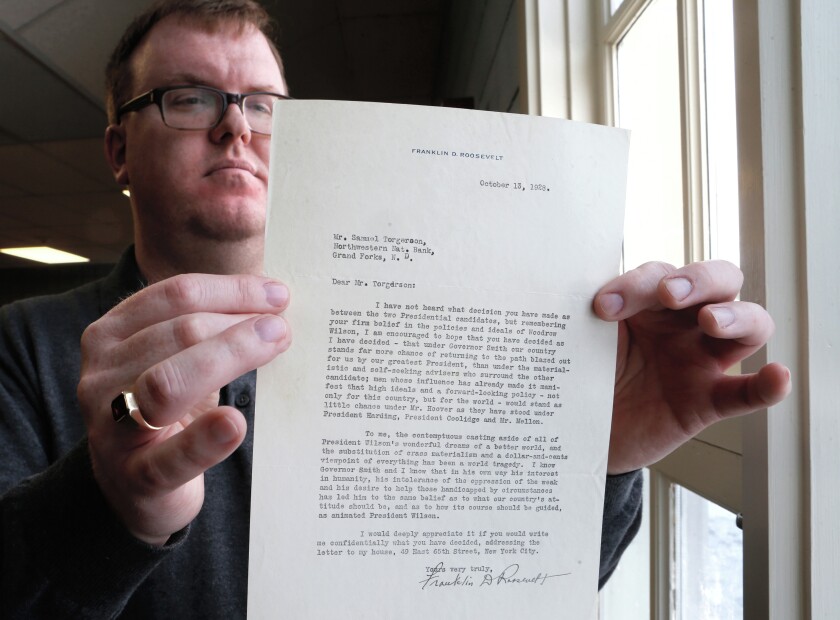

UND Special Collections Archivist Curt Hanson displays an historic letter from Franklin D. Roosevelt to Grand Forks banker Samuel Torgerson at the UND Chester Fritz Special Collections Library recently. photo by Eric Hylden/Grand Forks Herald

“We’re still always worried about the people surrounding the candidates,” he said. “Even though this was written in 1928, those same issues, and perspectives and arguments come up today.”

Roosevelt wrote that Wilson’s “wonderful dreams of a better world” were cast aside in favor of “crass materialism and a dollar-and-cents viewpoint of everything,” an act Roosevelt viewed as a “world tragedy.”

“I know Gov. Smith and I know that in his own way his interest in humanity, his intolerance of the oppression of the weak and his desire to help those handicapped by circumstances has led him to the same belief as what our country’s attitude should be, and as to how its course should be guided, as animated President Wilson,” he wrote.

Though it may be surprising to see a future president writing such a letter to a Grand Forks banker, at the time, the two men would’ve essentially been on the same political level, Hanson said.

Roosevelt and Torgerson were doing similar things, just in different parts of the country. They were both Democratic Party insiders, and likely delegates who attended the Democratic convention. Though Roosevelt would soon take over Smith’s position as governor, he hadn’t yet.

“So even though FDR went on to become one of our great presidents, at the time that he sent those letters, he’s reaching out to a fellow party insider just to shore up support for Al Smith,” Hanson said.

They certainly weren’t always the best of friends who saw eye-to-eye on everything, he said. This was especially clear once Roosevelt became president and introduced the New Deal, a set of policies that Smith was a very vocal opponent of. Different sources say this opposition could be borne from jealousy, or perhaps a belief that the policies were unconstitutional.

Torgerson’s response to Roosevelt, dated Oct. 16, 1928, said he was a strong supporter of Smith’s, and has been exerting his influence in Smith’s favor “in a quiet way.”

“I feel that due to the ability that Gov. Smith has shown in his present office and to the many progressive measures that he has advocated during his present term he is entitled to the support of all progressives in the country,” Torgerson wrote.

He also mentioned ministers in Grand Forks who have regularly devoted their pulpits to “stump speaking,” or giving a political speech, something Torgerson viewed as bigoted and intolerant.

“Churches are supposed to be politically neutral,” Hanson said. “And so, occasionally, and especially when pastors or clergy speak to the ‘right’ — to conservative causes — people in the ‘left’ are always like, ‘Well, let’s tax the churches. If they’re not truly going to be neutral, then let’s tax them.'”

Torgerson wrote that his own Congregational Church’s trustees decided unanimously against allowing political talk to take place in the church after being approached by an anti-saloon political speaker.

Torgerson explained that he couldn’t say which way the election would go in North Dakota, but he believed Smith would receive a large number of votes from farmers. He confessed his reluctance to make any predictions, and attributed it to the false certainty he had that Robert M. La Follette would carry North Dakota in the previous election.

Hanson suspects Torgerson was just trying to be positive, or perhaps was in somewhat of an echo chamber, primarily spending his time with people who shared his beliefs.

“Grand Forks, historically, has been one of the more liberal counties of our state,” Hanson said. “When you step out of the county of Grand Forks, the city of Grand Forks, it’s not that way at all.”

The race between Smith and Hoover was “not even close” in North Dakota, he said. Hoover received 54.8% of the popular vote and all five electoral votes, according to The American Presidency Project.

“In addition to being a Catholic, (Smith) was against prohibition,” Hanson said “So he was already behind the eight ball here in our rural part of the Midwest.”

There was a lot of anti-Catholic bias and propaganda circulating at the time; it was believed that if you voted for Smith, you were voting for the Pope.

“‘He’s a papist; he can’t be trusted,'” Hanson said. “(People said) that sort of thing.”

Nationwide, Hoover received 58.2% of the popular vote and 83.6% of the electoral vote.