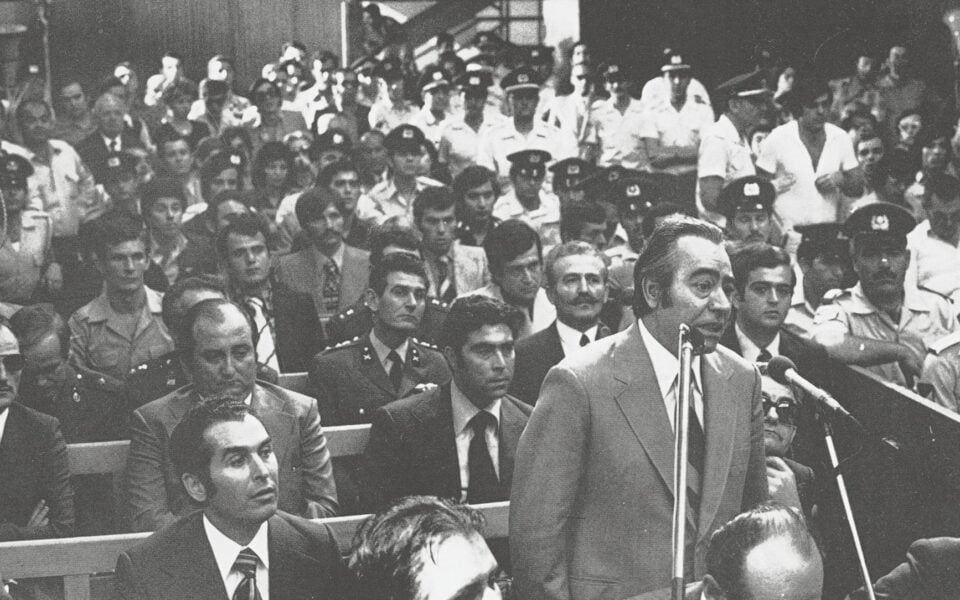

A torturer of the Greek dictatorship is seen during a trial against the enforcers of the regime, on October 10, 1975. The court sentenced them to life in prison. In Spain, such agents of the dictatorship never faced a court of law for their crimes. [Michalis N. Katsigeras/‘Greece, 20th Century, The Photographs’

The April 1967 military coup in Greece was not an isolated authoritarian parenthesis in history. On the contrary, it was part of a wider geopolitical space that also included other countries in Southern Europe, such as Spain and Portugal. The common elements in these countries were chauvinism, nationalism, fierce anti-communism, and selective extroversion – mainly through tourism. However, in contrast to the dictatorships of the Iberian Peninsula, which were established in the interwar years and survived for decades, the emergence of the colonels’ regime in Greece was a solitary, new phenomenon in the Old Continent of the 1960s.

The collapse of those regimes was equally uneven. In Greece and Portugal, the fall came as a result of crises outside their borders: In Greece’s case, it was the Turkish invasion of Cyprus in 1974 and for Portugal it was the colonial wars in Africa. In Spain, the Franco regime itself was forced into its own transformation, by committing institutional “suicide.” The infamous Spanish Amnesty Law of 1977 released political prisoners, but also guaranteed impunity for those who participated in crimes, as was the case in Greece. The absence of transitional justice in Spain created a gap in collective self-awareness. The logic was, we forget the past in order to move forward. But at what cost? There was no care for the victims, no monuments, no museums. The demand for memory and justice essentially came from society only in the 2000s in relation to the right to exhume and identify the remains in the hundreds of mass graves from the civil war era, so that the victims’ families could finally get closure.

The historical memory movement that emerged made it clear that civil society can reverse institutional omissions. The cycle of legislative interventions, under the title “Laws of Democratic Memory,” which began in 2009 and which led, among other things, to the removal of Franco’s bones from the mausoleum in the Valle de Cuelgamuros (Valley of the Fallen), was a result of this grassroots pressure.

In Spain, therefore, the collective memory of the dictatorship remains controversial and deeply politicized. In the current events to mark the 50 years of Spanish democracy, the conservative opposition People’s Party (Partido Popular) is always invited, but never participates. That is because, while in Greece, the conservative party that guided the transition to democracy distanced itself greatly from its previous self, the Spanish right has never irrevocably renounced its sinful past and continues to consider the discussion about the past as “stirring up passions” with dark motives. In Spain, titling a conference “50 Years Since the Death of the Dictator” is still considered provocative by a section of public opinion. A simple poster for an event criticizing collaborators of the Franco regime can provoke public confrontation.

The public history of Francoism remains, therefore, a hotly contested field. In my academic work, I see every day that questions about the past are more pertinent than ever. Younger generations in Spain are often unaware of what really happened during the period of the Franco dictatorship. My students emphasize again and again that “we were never taught why Franco’s regime was problematic.” The result? There is a youth that flirts with a renewed, embellished version of Francoism, with an emphasis on its somewhat mystical symbols. The slogan “We lived better with Franco” tends to dominate social media, and the far-right Vox party draws part of its influence from this mnemonic failure.

By contrast, in Greece, April 21 was denounced from the beginning as a traumatic event. Anti-dictatorial resistance became the dominant discourse and memory, and was institutionalized through symbols and heroic narratives. The EAT/ESA torture site of the Greek Military Police became a monument, actor and anti-junta activist Melina Mercouri became a minister, the murdered lawmaker Alekos Panagoulis gave his name to a road, and November 17, 1973, when tanks crashed through the gates of the Athens Polytechnic, a school holiday.

This does not mean, of course, that memory in Greece is not selective. We remember the Polytechnic uprising as the ultimate symbol of the anti-dictatorial struggle, but we do not ask ourselves enough about the absence of systematic resistance in the country. Which youngster today knows anything about the famous “Greek case” in Strasbourg, when Greece was forced to exit from the Council of Europe due to the regime’s use of torture – and why are these links of international solidarity missing from the teaching of modern Greek history? We systematically ignore the very nature of the regime, its populism, or the fact that it benefited many people – not to mention the memory gaps in relation to what happened with Cyprus.

Even with these shortcomings, the fact that this past was discussed and partially metabolized by previous generations at least does not create an abstract relationship with it. Despite the rise of the far-right in our country, it does not seem to be part of a generalized, diffused nostalgia for the colonels – at least for now.

Today, 50 years later, memory and amnesia remain active. While in Greece the dominant narrative seems to have stabilized, despite the occasional shots against the “Polytechnic generation,” Spain is now experiencing a belated confrontation with its dictatorial past. The question is whether the new, alienated generations themselves will demand new narratives and more just ways of commemorating the past. Memory needs processing, not repression, and political choices that will look the past right in the face, not only for reasons of justice, but also for reasons of democratic education. Here, too, perhaps Spain can learn something from the Greek case.

Kostis Kornetis is a professor of contemporary history at the Autonomous University of Madrid (Universidad Autonoma de Madrid), and adviser to the Spanish government on matters of historical memory.