The Slash” is the northern border’s version of “The Wall.” But where a wall creates a barricade, the Slash creates an opening.

The name feels a bit like an onomatopoeia, describing the 20-foot-wide, 1,349-mile-long clear-cut of spruce and fir trees that tower over the lakes and blanket the mountainsides of a land so big and untamed it doesn’t feel like it could belong to anyone.

The U.S. and Canada officially agreed on the co-management of the Slash when the International Boundary Commission was created in 1925, but the razing of trees to mark the 49th parallel began in the 1800s, to simply let the “average person” know that they are “on” the agreed-upon border. Today, the U.S. and Canada are each responsible for funding the maintenance of 10 feet (or 3 meters) of their respective sides of the Slash’s center line. That requires a $1.6 million annual budget for the U.S. to cut back any encroaching wilderness and maintain the cameras that surveil more remote stretches of the Slash. The U.S. government’s half of that bill costs each taxpayer between a half-cent and a penny every year. But at this moment, what’s crossing the border — and what’s not — is coming at a much higher price.

The “Slash,” the physical representation of the Canada-U.S. border, which is the longest international border in the world. | Forest Woodward for the Deseret News

The “Slash,” the physical representation of the Canada-U.S. border, which is the longest international border in the world. | Forest Woodward for the Deseret News While this region has a violent colonial history and the establishment of the United States and Canada bifurcated Indigenous nations and ecosystems along the 49th parallel, the world’s longest international border — 5,525 miles with 120 land ports of entry — has been considered peaceful for more than 100 years since the signing of the border treaty of 1908. Personal, political and economic relationships have been not only peaceful, but truly friendly and prosperous. The trade relationship between the two nations is one of the biggest in the world, with Canada and the United States both serving as each other’s largest export markets.

However, after President Donald Trump referred to Canada as “the 51st state” and announced a 25 percent tariff on Canadian goods, a trade war has broken out. Canada responded immediately with its own retaliatory tariffs. Since then, Canada and the U.S. have been flinging counter-tariffs back and forth on goods such as lumber, dairy, steel, aluminum and electricity.

It’s a fraught moment that feels upside down, with the southern border between the U.S. and Mexico being quieter than usual while tension in the north flares. Both Canadians and Americans living in border towns are trying to maintain a sense of normalcy, but some are beginning to question if top-down politics has the power to shake the foundations of what makes this region unique and peaceful. Many wonder what will remain, and what won’t, in the aftermath.

A casual affair

“Tell ya what, up here’s about as close to heaven as you can get,” says Lester “Bud” Gray, a rancher born and raised on the Blackfeet Indian Reservation. At a cafe on the reservation in northwest Montana, just 12 miles south of the Canadian border, Gray started his morning with some coffee and a casual three-hour cribbage session with his two friends, Pat Schildt and Stormy Burns, before heading back out to care for his cattle.

Despite what the news cycles bring, Lester “Bud” Gray and his friends have a constant: Cribbage. | Forest Woodward for the Deseret News

Despite what the news cycles bring, Lester “Bud” Gray and his friends have a constant: Cribbage. | Forest Woodward for the Deseret News “But wait ‘til the wind comes, then it’s hell,” he laughs. After a couple of games, the conversation shifts from the winter duties of feeding livestock to politics. The three men shake their heads at recent federal employee layoffs and the chaos of international relations and executive orders that have flooded the news lately.

Schildt, who has been constantly cracking jokes while consistently losing in cribbage, switches his tone. “People are going to pay with their lives, their livelihoods.”

“People are going to pay with their lives, their livelihoods.”

He runs a domesticated herd of bison on land with a whole handful of borders that also delineate his property line: The Blackfeet Indian Reservation, Canada, the United States, Montana and Glacier County. He says that his bison once busted through the fence and made their way into Canada, only to later find them huddled along the fenceline elsewhere waiting to be let back in. In addition to his bison crossing every so often, he says that many people’s lives and businesses are naturally integrated on each side of the border. His mechanic is north of the border, and it’s not uncommon for his neighbors to buy animal feed from each other or get groceries on the opposite side of where they live.

Human-made things also snake above and below ground across the border. While the population thins out along the northern border of the United States, most Canadians — 2 out of 3 — live within 62 miles of their southern border. Pipelines, reservoirs, electric transmission lines and industrial goods — nearly $2.6 billion worth of stuff — cross the border each day, according to the U.S. Department of State. The trade war has thrown all of these goods, and relationships, into a tailspin. For example, Ontario Premier Doug Ford slapped a 25 percent surcharge on electricity Canada supplies to Michigan, New York and Minnesota in March. It has since paused, but Ford says he is not afraid to “increase this charge” or “turn off electricity completely” if the U.S. escalates tariffs.

But up here (or down there, depending on who you are talking to), there is some immunity to human drama. It’s easy to imagine that more animals — as big as grizzlies and as small as ants — cross the border each day than people. The landscape is vast, and while far from empty, it’s hard not to feel a sense of awe and appreciation for it.

As you get closer to the Piegan Port of Entry border, bison dot the landscape on both sides of the highway (Schildt’s herd is on the east side). Chief Mountain, a sacred place for the Blackfeet, juts up from the plains into sheer walls of 600-million-year-old rock piled atop formations that are at least 400 million years younger. Set against the backdrop of the mountain, the drab government buildings and sleepy border crossing feel extremely insignificant. Silly, really. The Rocky Mountains strut north and only a slight shift in their name indicates any difference in their national identity becoming the “Canadian Rockies” as they cross the border into Waterton Lakes National Park.

For the average American or Canadian citizen, crossing the border is generally a casual affair. There is even an outdoor barbecue at one of the nearby crossings — a friend told me of a time a border agent had him wait a moment while he went to flip the chicken he was grilling.

Mike Bently, originally from Michigan, moved to Fernie, British Columbia, during the Vietnam War because he didn’t believe in “killing for peace.” | Forest Woodward for the Deseret News

Mike Bently, originally from Michigan, moved to Fernie, British Columbia, during the Vietnam War because he didn’t believe in “killing for peace.” | Forest Woodward for the Deseret News Pulling up to the Piegan Port of Entry, a young border agent asks the same questions as always. “Where are you going? For how long? Do you have tobacco, alcohol or firearms?” In less than one minute, speed limit signs swap from miles to kilometers per hour, the road that was once Highway 89 is now Highway 2, and the U.S. is in the rearview mirror.

The first town north of the border on Highway 2 is Cardston, which was settled in 1887 by members of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints traveling from Utah. A young man on a very tall horse trots down a road just a few blocks off the historic main street. Shayde Primrose, a senior in high school, wears a black cowboy hat and is easy to talk to. “I don’t pay much attention to what’s going on down south,” he says, “but my mom sure does, and she doesn’t like any of it much.” In addition to being a student, Primrose is a horse trainer. A woman has hired him to train this particular horse for racing. The horse’s name is Donald.

Search for the right balance

At a coffee shop in Blairmore, Alberta, a group of locals huddled together at a table, discussing the recent news of a family of Venezuelans trying to cross the border from Montana into Alberta on a night that was a bone-chilling minus 22 degrees. “How did they get all the way up here?” one man asks. Canadians are not used to people attempting to cross the border from the U.S. However, numbers have increased both ways in the past few years. First, Trump accused Canada of not being harsh enough on illegal crossings into America. U.S. Customs and Border Protection says 23,721 people were apprehended last fiscal year crossing its northern border, up from the 2,238 caught two years prior. That is a marked increase, but still nowhere near the 1.5 million apprehensions U.S. border agents made at the southern border last year. In response, Canada enacted stricter visa policies and added two helicopters and a fleet of thermal-detecting drones to their border security, and data shows that there are fewer attempted illegal crossings from north to south this year than at the same time last year.

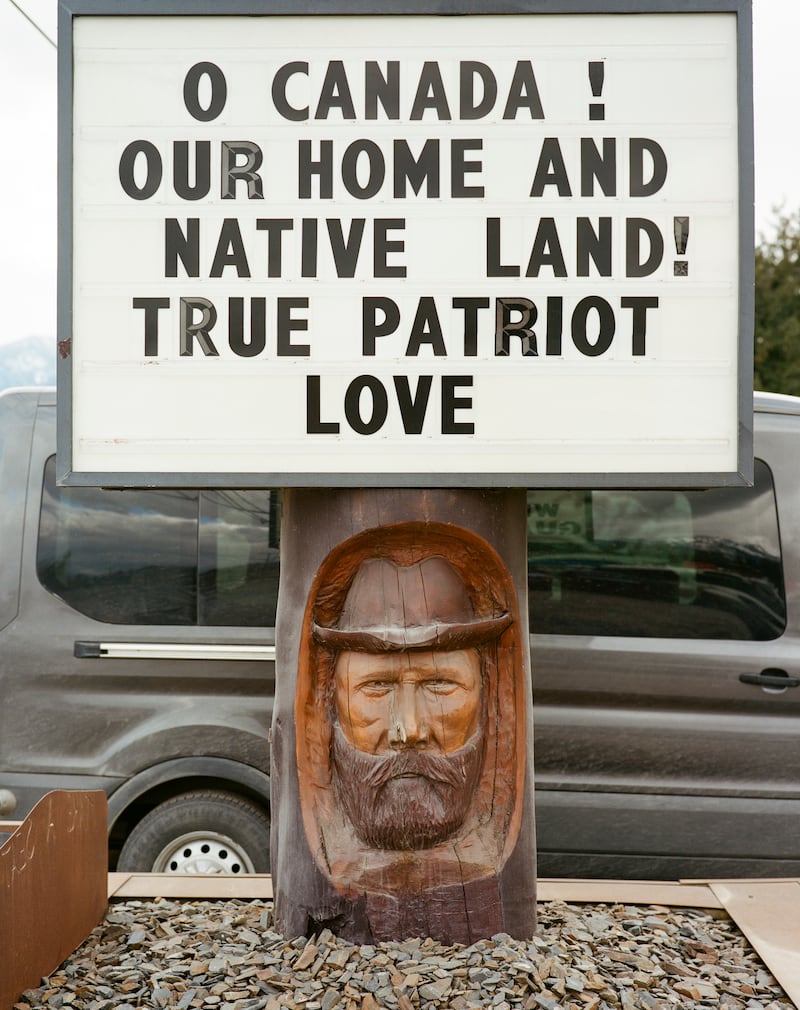

In response to President Trump’s provocation of the country, Canada’s patriotism is surging, with 78 percent of Canadians making an effort to buy more Canadian products, according to a recent Angus Reid poll. | Forest Woodward for the Deseret News

In response to President Trump’s provocation of the country, Canada’s patriotism is surging, with 78 percent of Canadians making an effort to buy more Canadian products, according to a recent Angus Reid poll. | Forest Woodward for the Deseret News However, as sweeping deportations have come into effect across the States, asylum-seekers are reportedly fleeing north, attempting to make it out of the U.S. and into Canada to avoid being deported. While data has not been released for 2025, government news releases suggest the number of these asylum-seekers escaping into Canada is rising. In Alberta, preliminary data shows that up to 20 people have been apprehended crossing illegally so far this year. In comparison, only seven people were intercepted crossing the border illegally in Alberta in all of 2024.

And while illegal border crossings seem to be rising, the official border crossings, where Americans and Canadians drive through every day to shop, eat, visit family, or even just go hiking or skiing, are eerily quiet. According to U.S Customs and Border Protection data, nearly 500,000 fewer travelers crossed the border from Canada into the U.S. in February 2025 than in February 2024.

But up here (or down there, depending on who you are talking to), there is some immunity to human drama.

“It’s unsettling,” says a woman working at the Duty Free shop on the Canadian side of the border at the Rooseville crossing. Normally, after work on a day like today, she tells me she often drives to Eureka, Montana, to buy groceries, since it’s much closer than driving to Fernie, British Columbia. But this morning, her friend went to buy a few groceries and received a 25 percent tax on them when she came back over the border. “It just no longer makes sense,” she sighs.

Shayde Primrose, a senior in high school living in Alberta, doesn’t pay much attention to the news cycle, instead staying busy training horses. | Forest Woodward for the Deseret News

Shayde Primrose, a senior in high school living in Alberta, doesn’t pay much attention to the news cycle, instead staying busy training horses. | Forest Woodward for the Deseret News But the fact is, folks have to keep making life make sense up here. And so, amid the cafe-stop lunches and the drives to the nearest market, they find ways. At a coffee shop in Fernie, a blonde woman wearing a beanie sitting next to me can’t help but notice that her 6-month-old baby and mine are about the same age, so we strike up a conversation. In between swapping stories about sleep deprivation and starting solid foods, she mentions that her husband is American and they go back and forth often. I ask her if they are worried about the politics of it all. “My husband isn’t, but I am,” she says. “Honestly, it creeps me out. I am feeling World War II vibes.” She then smiles, hands me her computer and asks me which pattern of bibs-with-sleeves she should buy.

Just under the surface of even the most pleasant interaction or expression is a feeling of deep concern and uncertainty. It’s difficult to navigate when overarching political tensions and contentment within our daily lives are constantly battling. It’s a practice of searching (but never actually finding) the right balance.

When U.S. and Canada connect

The Slash is not always easy to find — often far away from any roads or trails. Turning off the main highway, up a dirt road still packed with ice, I leave the car behind and walk through spruce and ponderosa. Then, suddenly, there’s an opening. Walking into the middle of the clear-cut, the line looks like it reaches out in both directions forever, only pausing to hop across the blue waters of Lake Koocanusa before picking back up and rising into the next mountain range across the valley. Lake Koocanusa’s name is a blend of “Kootenai” (one of the names of the Indigenous nation whose traditional homelands it is in), “Canada” and “USA,” but the word “Koocanusa” sounds nothing like any of those root names when you say it aloud.

Standing here, I remember reading about something President Ronald Reagan said in 1988, after signing a free-trade pact with America’s neighbor on the northern border: “Let it forever be not a point of division but a meeting place between our great and true friends.”

There are different ways to define this place we’re at, and to think about this “slash.” Perhaps, in the etymology of the word, this name wasn’t just meant to invoke the image of a slash that cuts two countries apart, like a sword slicing through the forest and national identity, but also a slash — a symbol of “either/or.” Of an indication that things are related enough to be separated by only the most marginal of lines.

The outcome of the trade war is still unclear, but Trump’s threats of future tariffs and the challenge to long-standing agreements hang in the air. What is clear is that, right now, trust in the U.S. as a reliable ally and “true friend” is in question.

The breeze is erratic and blustery as another storm hovers above. The sun is setting. The trees on the edge of the Slash sway back and forth, alternately leaning toward and away from each other. It smells of fresh earth and evergreen. In the negative space between the two countries, it becomes easier to feel what connects us.

This story appears in the May 2025 issue of Deseret Magazine. Learn more about how to subscribe.