By Damian Flanagan

I have an old friend who tends to post slightly unusual material on social media. He is British guy living in Japan for many long years and always has himself wearing sunglasses in a kind of “gangster chic,” quite often accompanied by young attractive Japanese women and sometimes accompanied by the night owls and bar flies of Osaka’s night-time demi-monde.

At first, I must admit that I didn’t quite grasp the purpose of the persona he adopts or the pictures he posts. Elements of it seemed slightly adolescent for someone rather advanced in years, but finally he put up a post that explained his philosophy and all became clear. In fact, I have rather become a convert to his way of thinking.

When he first came to Japan some decades ago, he recalled, he used to think of himself as British. But gradually he became accustomed to Japanese ways of doing things — the punctiliousness and precision and hygiene of Japanese services for example, the high quality of its food, its sense of community, law and order, honesty and respect for tradition. He breathed all this into his pores, without being accepted into Japanese society itself.

Then he eventually went home to Britain. But now he found that he didn’t actually feel himself to be British anymore, was uncomfortable at the often disappointed in the ways of his own country. He hankered to go back to Osaka and when he did move back, he suddenly realised that Osaka was in fact his true home.

In Japanese eyes, he was always a foreigner, a “gaijin,” but no longer “British” either, he felt that his true identity was that of an “Osaka gaijin,” an “outsider” who feels truly at home in Osaka. He also argued that across Japan there are a network of “Japanese Gaijin,” all of whom are foreigners who feel most at home in Japan and that he was merely a representative of the Osaka chapter of the network.

Far from wanting to be Japanese, many actively enjoy being “gaijin.” There is often a community spirit amongst the gaijin in Japan that effortlessly brings together interesting characters from all around the world and all of them enjoy a kind of mini-celebrity status amongst many Japanese — hence the pictures of attractive Japanese partners and good times in Japanese bars.

In an age in which the mantra of “diversity and inclusivity” is repeated as the save-all-souls religion, I began to think about this intriguing idea that there are these people who actively enjoy being “othered,” who want to stand apart and outside the mainstream.

I recall that from my earliest days in Japan, there were often people who would bridle at the rough word “gaijin.” The polite term for foreigner in Japanese is “gaikokujin,” and in some contexts, “gaijin” has a feel of contempt and disdain mixed in. There are many people who slave to be accepted in Japanese society and many examples of people who have mastered the Japanese language, adopted Japanese nationality, married Japanese partners and raised Japanese children. But the reality is that, for all their efforts, nearly all Japanese people are still likely to look upon them as “gaijin.”

Many millions of words have been penned about the exclusionary nature of Japanese society and whether it might change in an era of ever greater international travel and cross-cultural influences. Americans seem to obsess about this subject. You have ethnically Japanese people in America who can’t speak a word of Japanese and know little of Japan’s culture who get bundled into the camp of “Japanese” or “Asian.” And you have people who are not ethnically Japanese, but who can speak fluent Japanese and have a deep knowledge of Japanese culture… whom Japanese people will insist on speaking to in English. Accusations of “racial profiling” and “othering” and “bigotry” and “non-inclusivity” all fly around and generate hundreds of articles of minor or major outrage.

A few years ago, The Japan Times ran an article written by a long-term Black American resident of Japan, who complained of the “empty seat” left next to him even on crowded trains as Japanese people kept a slightly fearful distance. There was an enormous response from lots of other foreign visitors and residents bewailing the same thing or berating the Japanese for their attitudes.

And then I’ve read quite a few articles by a White resident of Japan who holds a Japanese passport and is looked upon suspiciously every time he passes back and forth through passport control both of Japan and other countries.

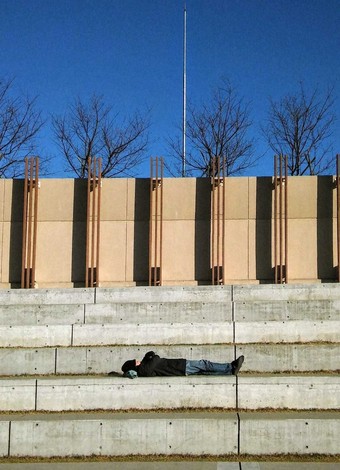

But in this world of confusion, full of people adopting identities that their outward appearance would seem to contradict, I’m quite taken by my friend’s active embrace of a “gaijin” identity. In this mindset, you don’t want to be anything else, thanks very much. You don’t want to be British, don’t want to be Japanese, don’t want to be “included.” You want to be excluded and be your unique form of you in a territory that “otherness” affords you.

I’ve come to understand that my friend is not an adolescent poseur, but quite a profound existential philosopher. He is like the characters of the films of Jean-Luc Goddard, part of a “Bande a Part” (A Band of Outsiders) and like some protagonist in “A Bout de Souffle”, he dons his regulation sunglasses as a signifier of that otherness.

Many years ago, when I was an earnest graduate student at Kobe University, my supervising professor would warn me that many of the long-term bar fly foreigners holding down English teaching jobs were “koku-tsubushi” (literally “husk crushers,” or wastes of time) and to be avoided. But he was wrong. Over the years I’ve appreciated the rich seams of gaijin to be discovered in the night-time bar world of Osaka and other places, and they are often some of the most fascinating and entertainingly unique characters you will ever come across.

(This is Part 58 of a series)

In this column, Damian Flanagan, a researcher in Japanese literature, ponders about Japanese culture as he travels back and forth between Japan and Britain.

Profile:

Damian Flanagan is an author and critic born in Britain in 1969. He studied in Tokyo and Kyoto between 1989 and 1990 while a student at Cambridge University. He was engaged in research activities at Kobe University from 1993 through 1999. After taking the master’s and doctoral courses in Japanese literature, he earned a Ph.D. in 2000. He is now based in both Nishinomiya, Hyogo Prefecture, and Manchester. He is the author of “Natsume Soseki: Superstar of World Literature” (Sekai Bungaku no superstar Natsume Soseki).