For Malta, British colonialism proved crucial to achieve full sovereignty and EU membership. If one tries to take a balanced view of colonialisation there are obviously the pros and cons. There is no doubt it involves the rulers and the ruled, as is also the case in today’s sovereign states, but liberal parliamentary democracies are run by rulers of integrity while sovereign authoritarian states hold the ruled in a fearful despotic stranglehold.

Great colonisers, like Rome and Britain, besides instilling discipline (and cruelty at times), also left positive legacies. If one doesn’t recognise the positivity of colonial culture transfer, a balanced discussion of colonisation is not possible.

In recent decades, the Maltese historical recollections scene has been predominantly very negative about the British one-and-a-half century colonial period, often pictured as nothing more than poverty of the masses ending in the Sette Giugno incident. In contrast, the two-and-a-half century occupation by the Knights of St John is lauded to high heavens and spared the dirty description of ‘colonisation’, when, in effect, it wasn’t much more than a feudal authoritarian state earning its living largely by piracy and slavery.

We have ample records of the grandeur of the Knights but practically nothing about the level of poverty of the largely peasant, scant population whose mother tongue was an Arab dialect. Even the few rich Maltese could not own a house in Valletta – this was not for the natives.

A typically biased detractor of our British colonial period is a recent regular columnist who sounds like a ghost from the ‘glorious’ Dom Mintoff times – our finest of the last 60 years of sovereignty, when we essentially were a Libyan ‘satellite’, experiencing a siege economy with the added help of China and North Korea. Suddenly our ‘enemies’ were the Western cultures. This 1970s- and 1980s-type propaganda continues today with NATO being blamed for all the world’s conflicts.

In one such recent feature in this paper, some Maltese workers’ wages and the price of staple commodities in the post-WWI period were quoted to quantify the level of poverty at the time.

I clearly remember other figures. In the early post-WWII years, my father’s wage as a primary school headmaster was £12 a month. With that he could afford to rent a big house with a big garden for £12 a year.

Most families lived in rented accommodation, which was plentiful and affordable. After 60 years of sovereignty, around a 100,000 of our population is classified as poor, and booming tourism has contributed significantly to housing cost inflation and widening of the gap between rich and poor.

So how come we have statues, public holidays and even plays and films about the Sette Giugno incident and nothing of the sort to commemorate the uprising against Napoleon’s troops, resulting in the death of several thousand Maltese? The Sette Giugno incident must have suited the propaganda of both large post-war Maltese political parties.

In the 1930s, an elitist section of our population regarded Italian culture as superior to the British one which, they felt, was alien to a ‘Latin’ people.

Furthermore, this section of our population had always felt they were Italian rather than Maltese and were very sympathetic to Italy’s then popular irredentismo (irredentism) movement, claiming Malta was an Italian island that needed to return to the motherland.

The unfortunately naïve youth, Carmelo Borg Pisani, was such an example of a Maltese claiming an Italian identity. These people forgot that language is foremost in national identity and our mother tongue was Maltese, not Italian.

The irony is that had the dream of our sympathisers of Fascist Italy come true we would never have become a sovereign state and EU member. After the Knights of St John, British colonisation definitely transformed us into a separate territorial entity from Sicily and Italy. If this hadn’t happened our flag today would be the Italian one, and we would be the tiniest, most southern and least important Italian region.

Instead, we are an economically successful independent state and EU member, because British colonialism gave us parliamentary democracy and a second official language, which is international.

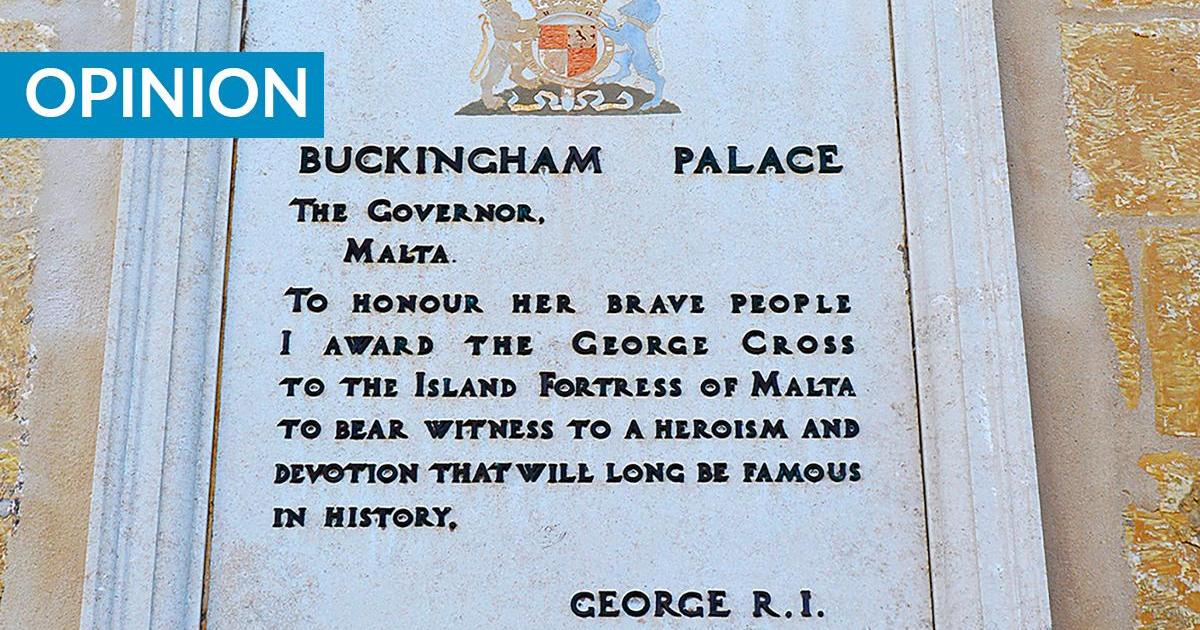

Some of us still peddle these petty claims that the George Cross, being a ‘foreign military’ emblem, should not be on our flag. This decoration is civil, and the UK NHS staff were awarded the George Cross for services rendered to the nation during the COVID pandemic.

Our George Cross records, in particular, around 15,000 Maltese killed in WWII. Their blood, and that of all the Allied military and civilians killed in Europe, is what has gifted us the freedom we enjoy today in the liberal parliamentary democracies.

It has been claimed the eight-pointed cross should be on our flag rather than the George Cross.

What is now known as the Maltese Cross was first used by the Duchy of Amalfi, in southern Italy, which is why this cross is one of four emblems in the centre of the Italian flag.

It was later adopted by the Knights of St John and some other related organisations. Nobody decorated us with this cross – we just grabbed it after Napoleon’s troops kicked the Knights out of Malta.

Both Italy and the Knights would say it still belongs to them.

Albert Cilia-Vincenti is a former UK and Malta senior public servant.