Countries in the Global South could benefit most from controversial solar geoengineering technologies to help mitigate climate change impacts. However, these countries also have the most to lose if the technology goes wrong, says Sandro VattioniExternal link of the federal technology institute ETH Zurich.

Ten years ago, the Paris Agreement set a goal to limit earth’s warming to 1.5 °C. Last year, the planet passed that limit for the first time. Despite efforts to halt global warming, greenhouse gas emissions continue to rise year after year.

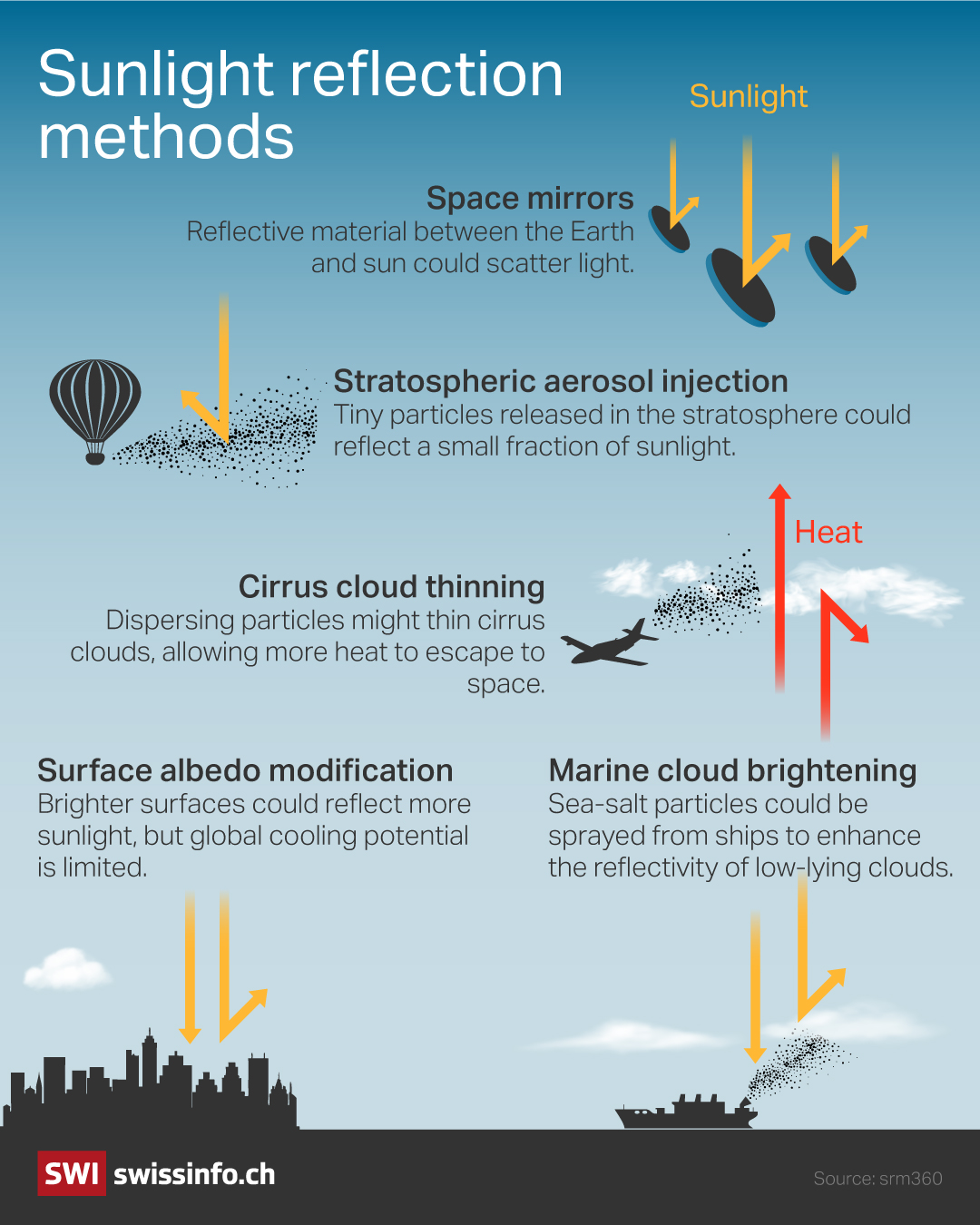

These dismal prospects for improvement have spurred research into so-called sunlight reflection methods (solar radiation management or SRM), also called solar geoengineering. SRM aim at reflecting more sunlight off the Earth and back into space, which would artificially cool the climate.

Proposals for SRM include the dispersal of tiny reflective particles at altitudes above 20 kilometres, where they would spread across the globe and reflect some of the incoming sunlight. Other proposals suggest creating or extending the life of sunlight reflecting clouds below altitudes of three kilometres.

>> What are the potential benefits and risks of solar geoengineering? Find out in this explainer:

More

More

Is playing with the sun to fight climate change worth the risk?

This content was published on

May 10, 2025

Reflecting the sun’s rays back to space to prevent climate change, known as solar geoengineering, is as controversial as it is intriguing.

Read more: Is playing with the sun to fight climate change worth the risk?

It must be clearly emphasised that SRM is not a substitute for emission reductions, and it is not a solution to the problem of climate change. At best, SRM, which are relatively cheap and can achieve a rapid cooling effect, could be a temporary supplement to emission reductions to avoid irreversible ecological and climatological tipping points. The net-zero target must not be lost sight of in the process.

While SRM would certainly cool the global climate, the technology is not without risks. That’s why such a global intervention needs international governance, including expertise from the countries most affected by climate change.

We need more research on the risks and benefits of SRM

Although it has been shown that SRM have the potential to efficiently reduce climate impacts, potentially saving millions of livesExternal link and billions of dollars of damage from climate change, other studies warn that SRM could be misused as an argument for delaying the phase-out of fossil fuel combustionExternal link.

Many of the potential risks and benefits of SRM are still uncertain. While everybody hopes that its use will not be necessary, we should be fully informed how SRM would affect the climate and society.

Some SRM could, for example, have adverse environmental side effects such as ozone depletion, changes in precipitation patterns and, most importantly, uneven global distribution of its potential positive and negative effects, which raises question about governance and global justice.

Further research is therefore needed to better understand SRM and its potential effects on different regions around the world.

Kai Reusser / SWI swissinfo.ch

The role of the Global South

Historically, the Global North is responsible for 92% of the cumulated greenhouse emissions. Meanwhile countries in the Global South are the most vulnerable to the impacts of climate change. SRM are therefore of paramount importance to the Global South. Should SRM ever be deployed and reduce climate risks, these countries would potentially benefit the most. Should its use fail, the vulnerable countries have the most to lose.

Because SRM are cross-border technology with global implications, the need for global coalition is essential. Initially, research on SRM was primarily conducted at universities in the Global North and funded by philanthropic sources. This is why the Degrees InitiativeExternal link was founded with the aim of increasing the participation of the Global South and to ensure informed and confident representation of developing countries.

With contributions from governmental and philanthropic sources mainly from the Global North the Degrees Initiative has established a research fund for scientists in the Global South to address locally relevant research questions about SRM and what it could mean for climate-vulnerable regions.

During the last few years, global funding for SRM research has risen sharply, underscoring the growing recognition of the topic’s importance. Although the share of funding going to researchers in the Global South is also growing steadily, at 2% it is still disappointingly low.

Last week, the Degrees Initiative convened a global forum on SRM in Cape Town, South Africa, with the aim of ensuring a balanced representation from the Global South and the Global North.

While the most prominent voices at the conference came from the Global North, the researchers funded by Degrees are ensuring that Southern expertise is at the center of the SRM assessment.

For example, Roxann Stennett-Brown from the University of the West Indies in Jamaica investigates how SRM would affect agriculture in Jamaica and the Caribbean. While Professor Heri Kuswanto from Institut Teknologi Sepuluh Nopember in Indonesia analyses the local effects of SRM on temperature and precipitation extremes, Romaric Odoulami from the University of Cape Town studies these effects for different regions in Africa.

With its own expertise on the topic, the Global South is better positioned to form its own opinion on whether to deploy SRM. This expertise is crucial in answering important questions: Who has the power to decide if, how and to what extent SRM should be researched and deployed? Due to its apparent simplicity, could it be possible that a single major economic power or a coalition of countries could start applying SRM, with global implications and significant risk of conflict?

Especially in an age of global division, these questions show how important an internationally-balanced governance of SRM will be. While some participants of the conference advocated immediate small-scale trials of SRM, others called for a non-use agreement or a moratorium on SRM until research has reduced the uncertainties of the underlying risks and benefits.

What role does Switzerland play in SRM?

There are several scientific groups at ETH Zurich, the Paul Scherrer Institute and the Physical Meteorological Observatory in Davos conducting research on SRMExternal link. Above all, however, Switzerland is seeking to take on a leading role in the governance of SRM by placing the issue on the agenda of the United Nations.

After a first attempt in 2019, Switzerland has submitted a resolution to the United Nations Environment Assembly last year calling for an international assessment of SRM. However, the resolution had to be withdrawn due to disagreements among countries over the scope of the report and the actors involved. Thus, a comprehensive international assessment of SRM is still lacking.

Nevertheless, the efforts show that Switzerland is prepared to take responsibility in establishing governance. As a neutral country that is also home to the World Meteorological Organization (WMO) in Geneva, Switzerland is ideally placed to take on this role. Given the current geopolitical situation, the rapidly increasing global impact of climate change around the globe, as well as the rapidly increasing funding for SRM research, it is likely that the issue will gain further importance in the near future.

To support the discourse and decision-making on SRM, it is essential to establish binding governance mechanisms and to reduce the uncertainty about the risks and benefits of SRM through coordinated research and accurate communication of the results.

Edited by Gabe Bullard/vdv

Articles in this story