BROMONT, QUE. — To run the $250-million machines that print the world’s most advanced semiconductors, chipmakers rely on an incredibly thin film produced in the woodlands of Quebec’s Eastern Townships.

The film, called a “pellicle,” is made at a Teledyne Technologies plant in Bromont’s industrial zone. The city, an hour’s drive from Montreal, is key to Canada’s ambitions of capitalizing on America’s desire to reduce its reliance on Taiwanese semiconductors. But Ottawa’s hopes could be dashed by the Trump administration, which has threatened tariffs on chip imports and signalled it wants more electronics manufactured within the U.S. itself.

Talking Points

Hardware executives say Canada should focus its semiconductor strategy on what it does best—including packaging, sensor production and optical connectors—to complement rather than compete with what the U.S. is building

In response, Prime Minister Mark Carney has promised to shore up the Canadian semiconductor industry. Hardware executives say Canada should focus on parts of the supply chain where it already has clear advantages, instead of trying to rival the U.S. Others are calling for federal and provincial governments to support homegrown companies that keep their intellectual property (IP) and profits in Canada, rather than trying to attract multinationals.

Pellicles are “very tricky to make,” said Sebastien Michel, vice-president and general manager of Teledyne’s micro electromechanical systems division. The frosted grey film is about the length of and slightly wider than a postcard, but just a few nanometres deep—it’s like trying to roll a sheet of pastry for a pain au chocolat so it’s thinner than the eye can see.

The pellicles go into extreme ultraviolet (EUV) lithography machines, which firms like Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing and Intel use to make the world’s most powerful semiconductors for AI, smartphones and other applications. In simple terms, the equipment works by bouncing the light off a “mask”—a mirror painted with one layer of the chip’s design—onto a silicon wafer. The machine draws minuscule lines again and again, so a single stray particle can create major defects across an entire production run of processors. Pellicles keep debris off the masks.

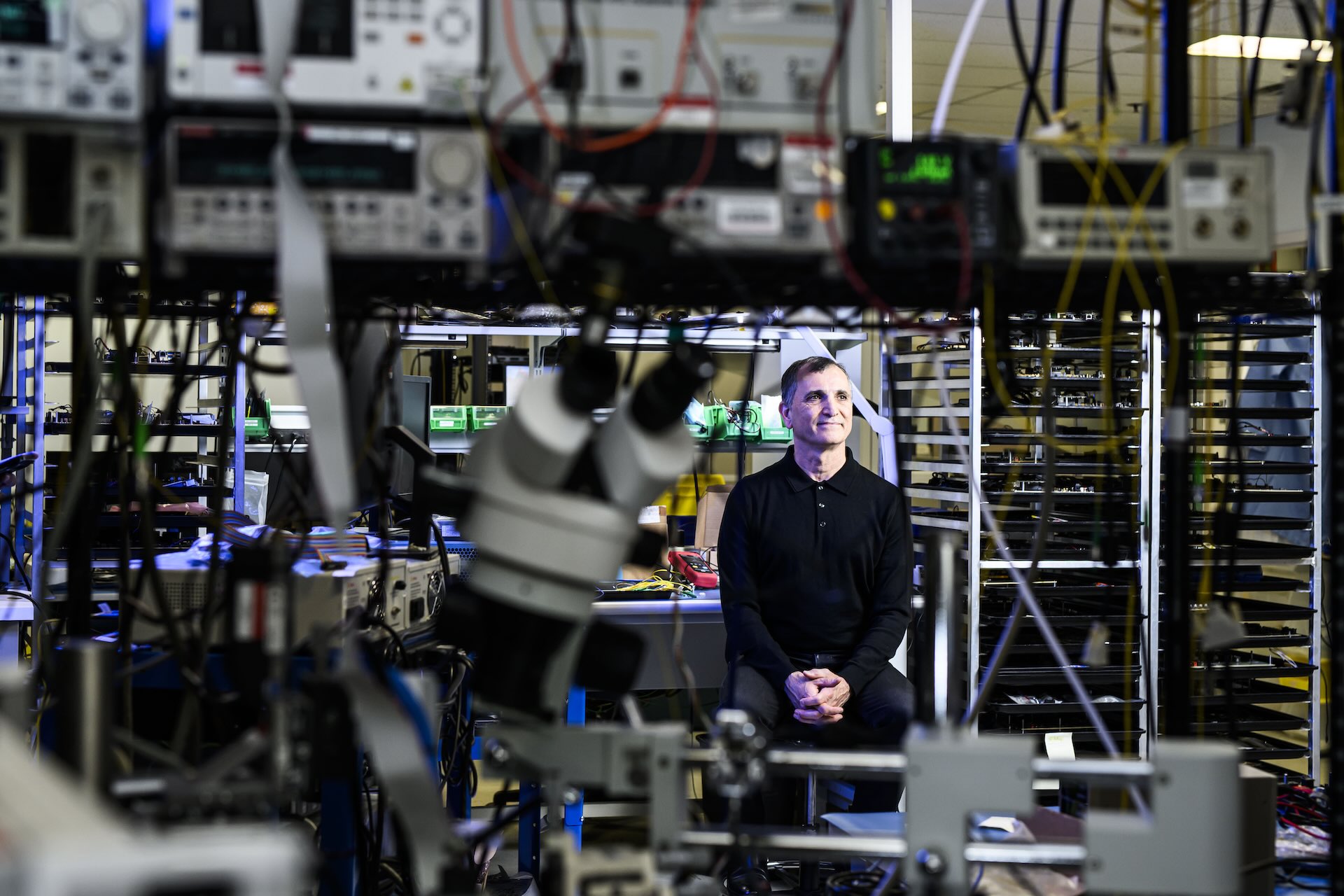

Sebastien Michel, vice-president and general manager of Teledyne’s micro electromechanical systems division, at the plant in Bromont, Que., which he oversees. Photo: Roger Lemoyne for The Logic

Dutch giant ASML, the world’s only supplier of EUV machines, invented the special film and, with Teledyne, worked out how to industrialize it. Making pellicles is now “a significant business” for the Bromont plant, said Michel, who’s worked there for over two decades.

Teledyne, headquartered in Thousand Oaks, Calif., acquired the facility in February 2011 when it bought Waterloo, Ont.-based DALSA. The 435-person Bromont plant also manufactures sensors that are built into space equipment to detect infrared light and other types of radiation, as well as micromirrors for the switches in telecommunications networks and data centres. In March, the federal Strategic Innovation Fund (SIF) awarded Teledyne $8 million to help pay for $42 million in equipment upgrades.

Across the road in Bromont, the SIF is also providing IBM with almost $270 million in financing to expand its plant, the largest packager of semiconductors in North America. In April 2024, site lead Stephane Tremblay told The Logic that IBM wanted to win the business of chipmakers that are building new fabrication facilities in the U.S. with funding from the US$52.7-billion CHIPS and Science Act. Under then-president Joe Biden, Washington was eager to collaborate with Ottawa on semiconductor supply chains.

Bromont, better known as a ski resort, may seem an unlikely place for so much chip manufacturing activity. IBM and Teledyne’s plants opened in 1972 and 1973, respectively, with the city able to provide both a skilled workforce and relatively unpolluted air, which makes it cheaper to run the clean rooms in which sensitive electronics must be made, according to Marie-Josée Turgeon, CEO of Centre de Collaboration MiQro Innovation (C2MI). The city is also close to universities in Montreal and Sherbrooke and to Albany, N.Y., where IBM, GlobalFoundries and other big chip firms have facilities.

IBM’s Bromont plant is the largest packager of semiconductors in North America, and is getting a $1-billion expansion with almost $270 million in federal financing. Photo: Roger Lemoyne for The Logic

C2MI, which is partly funded by the federal and provincial governments, helps clients develop manufacturing techniques they can use to produce new hardware in commercial quantities. The organization works with startups spinning out of universities as well as large firms like IBM and Teledyne.

Canada’s unique semiconductor strengths, according to Turgeon, include Bromont’s ecosystem of companies doing packaging and micro-electromechanical manufacturing, as well as the cluster of firms developing photonics hardware in Ottawa. “It’s very important to keep that knowledge here” by helping to develop “the next generation of technology,” she said.

Hamid Arabzadeh, CEO of Ottawa-based Ranovus, has long argued that Canada needs a sharper semiconductor strategy focused on homegrown firms that generate IP rather than multinationals that just hire locals. Ranovus has developed optical technology that connects chips in AI data centres faster and more efficiently. The company, which manufactures its products in Ottawa, is leading a consortium bidding to build a national supercomputer, as part of a federal program to increase Canada’s AI computing capacity.

Last month, Ranovus announced a partnership with California chip startup Cerebras to develop a new computing system for the U.S. Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency. The deal could be a model for Canada’s semiconductor strategy, according to Arabzadeh. Ranovus can work with “big players that are way ahead of everyone else,” then bring some of that “proprietary knowledge” back to Canada, he said. Canada could also use Ranovus’s technology as a bargaining chip in the geopolitical game to decide which countries and firms can be part of semiconductor supply chains.

Ranovus CEO Hamid Arabzadeh has built his manufacturing operations in Canada, with final assembly of its hardware at its Ottawa headquarters. Photo: Justin Tang for The Logic

Under President Donald Trump, the U.S. wants to reclaim all semiconductor manufacturing from Asia, Commerce Secretary Howard Lutnick said last month. But the White House has also said it wants to renegotiate deals the Biden administration made with hardware firms for funding under the CHIPS Act.

C2MI’s smaller American clients are struggling with uncertainty about the CHIPS Act and semiconductor tariffs, according to Turgeon. Meanwhile, she said, larger U.S.-headquartered firms are trying not to draw attention to their Canadian facilities right now to avoid pressure to reshore them.

Teledyne’s Bromont plant hasn’t lost any business or faced challenges getting materials from suppliers, according to Michel, though some clients have delayed production of new products. There’s no American alternative to the Quebec facility for the specialized imaging sensors it manufactures, he said. “In the U.S., they don’t have that skill and that expertise.”

Competing head-on with the U.S. to make cutting-edge chips would be prohibitively expensive—new fabs can cost over US$20 billion. Michel, Turgeon and Arabzadeh all say Canada should instead focus on parts of the semiconductor supply chain where it has strategic advantages and can complement what the U.S. is building.

Whatever happens in Washington, Turgeon predicts Bromont’s hardware manufacturing ecosystem, now over a half-century old, will survive. “We’ll still be there, and we’ll still work on the next generation of technologies.”