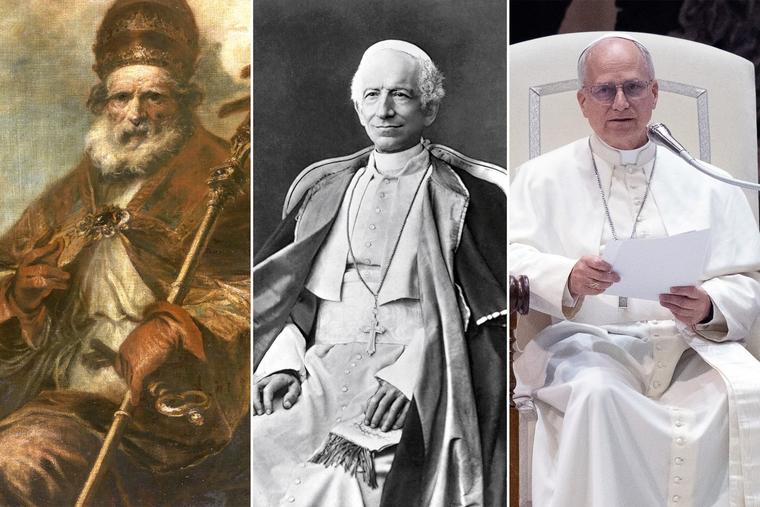

When Cardinal Robert Prevost was elected pope by the College of Cardinals on May 8, he chose to be called Leo XIV. In the annals of the papacy, that name evokes memories of both the first and last Leos to bear the name.

The first Leo was Leo the Great, who became pope on Sept. 29, 440, and reigned till Nov. 10, 461. The last Leo was Leo XIII, Gioacchino Vincenzo Raffaele Luigi, who was born on March 2, 1810, was elected pope on Feb. 20, 1878, and died on July 20, 1903.

Both Leos were pivotal popes who made lasting contributions to the Church, affecting everything from our understanding of Christ’s nature to the legitimate purposes of private property. Looking at both of their legacies may give us some insight into our newest Pope Leo.

The First Leo

Although he was not physically present, Pope Leo the Great played a decisive role at the Council of Chalcedon, which took place in 451. Chalcedon was a pivotal council, drawing together and reaffirming a long line of teaching against Christological heresies that had begun in 325 with the Council of Nicaea (the 1,700th anniversary of which we observe this year).

Although Nicaea taught authoritatively against Arius that the Son of God is fully divine, it opened additional questions about Christ, such as the status of his humanity. These concerns were then addressed at the Council of Constantinople in 381, which affirmed Christ’s humanity. The Council of Ephesus, which took place in 431, was then called to reject the heresy of Nestorianism, which argued that Christ must be two persons, human and divine, rather than just one divine person born of Mary.

Against the teaching of Nestorius, the Council of Chalcedon reaffirmed the teaching of the Council of Ephesus that the Son is one person, not two. And against the teaching of Eutyches and the Monophysites, the council clarified that in this one divine person that the Son is, there are two natures — one human and the other divine. To use the words of Chalcedon:

We confess one and the same Son, who is our Lord Jesus Christ, and we all agree in teaching that this very same Son is complete in his divine nature and complete — the very same — in his humanity. The character of each nature is preserved and comes together in one person … not divided nor torn into two persons but one and the same Son and only-begotten God.

The first Leo, Pope Leo the Great, did not travel to Chalcedon. Yet, his presence was felt in his letter to Bishop Flavian of Constantinople, read at the council. In response to his clear teaching on the person of Christ, the fathers present at the council proclaimed, “Peter has spoken through the mouth of Leo!”

Pope Leo the Great’s homilies on the Nativity of Our Lord provide me with refreshment every Christmas, and illuminate the truth about Christ. In his Sermon XXIII on the Nativity, he wrote about the two natures of Christ at the incarnation in these words:

Both natures [human and divine] retain their own proper character without loss: And as the form of God did not do away with the form of a slave, so the form of a slave did not impair the form of God. And so the mystery of [divine] power united to [human] weakness, in respect of the same human nature, allows the Son to be called inferior to the Father: but the Godhead, which is One in the Trinity of the Father, Son, and Holy Spirit, excludes all notion of inequality.

Thus, the First Leo was noted for clarity and depth in his teaching on the person of Christ who is true God and true man in one person, the Son of God, in whom “the Invisible made himself Visible.”

These ecumenical councils and debates about Christ’s true nature can seem like concerns of the distant past, but it is important to remember that they provided answers to heresies that we see cropping up in our own day. The Monophysite teaching finds echoes today in populist preaching here in Nigeria. The human nature of Jesus Christ is denied, or at least not affirmed, when the emphasis is on miracles and wonders.

We may expect Leo XIV to draw deeply from this First Leo to continue to tell the world who Jesus truly is. But we must also speak of another Leo — Pope Leo XIII.

The ‘Last’ Leo

The pontificate of Leo XIII was quite eventful. Leo elevated John Henry Newman to the cardinalate in 1879. He gave robust support to the study of ecclesiastical sciences. His encyclical on the study of Holy Scripture, Providentissimus Deus, in 1893 and the establishment of the Biblical Commission boosted the study of Sacred Scripture within Catholicism.

Two of his most impactful acts would prove to be the publication of two encyclicals: Aeterni Patris, on the restoration of Christian philosophy (1880), and Rerum Novarum, on capital and labor (1891).

Seeing the danger modern philosophies posed to the faith, Pope Leo XIII published Aeterni Patris to promote the study of the philosophy of St. Thomas Aquinas as a way of responding to challenges posed to the faith by atheistic philosophies of the modern era.

In the encyclical, Pope Leo XIII wrote about Aquinas in laudatory terms, calling him the “master and prince” of all Scholastic Doctors:

Far above all other Scholastic Doctors towers Thomas Aquinas, their master and prince. … He warmed the whole earth with the fire of his holiness, and filled the whole earth with the splendor of his teaching. There was no part of philosophy which he did not handle with acuteness and solidity.

Leo XIII recognized that Aquinas not only “vanquished errors of ancient times,” but that he still supplied “an armory of weapons which bring us certain victory” in conflict with contemporary falsehoods. In particular, Thomas distinguished reason from faith, but also joined “them together in a harmony of friendship.”

Pope Leo XIII reminded us of what is often forgotten today, even in intellectual circles within Catholicism: While there is a distinction to be made between philosophy and theology, the separation of one from the other is alien to the Catholic intellectual tradition.

Separation of philosophy and theology — rooted in the misconception of the mission of each — largely explains the crisis within Catholicism today. It’s an error that emerging networks of Catholic universities, including those in my own Nigeria, must take care to avoid. Authentic Catholic intellectual tradition learns from Aquinas that truths of reason and truths of faith are not in opposition, because they are taught by the same teacher: God, who does not contradict himself.

Pope Leo XIII’s other foundational encyclical, Rerum Novarum, looked to apply the insights of doctrine built upon the union of philosophy and theology to the challenges of the world.

Rerum Novarum was written in the wake of the Second Industrial Revolution and the publication of The Communist Manifesto by Friedrich Engels and Karl Marx, as well as Marx’s Das Kapital. In this landmark encyclical, Leo XIII defended the right to private ownership of capital, directly countering the claims of Engels and Marx.

Instead of a class struggle between owners of capital and laborers, a struggle prescribed and predicted by Marx as an inevitable means of attaining a classless society, Pope Leo XIII laid down principles that ought to guide the relations between workers and employers.

For instance, he affirmed the legitimacy of private property, teaching that God “is said to have given the earth to mankind in common, not because he intended indiscriminate ownership of it by all, but because he assigned no part to anyone in ownership, leaving the limits of private possessions to be fixed by the industry of men and the institutions of peoples.”

Pope Leo XIII also grounded his teaching in reason, writing that “private possessions are clearly in accord with our nature.”

At the same time, Leo XIII also made a strong case for the dignity of the worker who must be justly treated by the employer. He said, “Workers are not to be treated as slaves; justice demands that the dignity of human personality be respected in them, ennobled as it has been through what we call the Christian character.”

The Pope defended the nobility of “gainful occupations,” “as they provide him with an honorable means of supporting life.”

What is “shameful and inhuman,” however, is “to use men as things for gain and to put no more value on them than what they are worth in muscle and energy.”

Leo XIII called for employers to properly consider the “the spiritual well-being” of their workers and to “in no way to alienate him from care for his family and the practice of thrift.” He also taught that work must be suited to the age and sex of the worker.

What Pope Leo XIII affirmed in Rerum Novarum regarding the legitimacy of private property would be reiterated by the Second Vatican Council in its “Pastoral Constitution on the Church in the Modern World,” Gaudium et Spes. According to the Council,

“In making use of the exterior things we lawfully possess, we ought to regard them not just as our own but also as common, in the sense that they can profit not only the owners but others too” (69).

Pope St. John Paul II would add his voice to the reiteration of this teaching in his encyclical Centesimus Annus, published on the 100th anniversary of Rerum Novarum. He taught that the right to private property allows man to fulfill himself by “using his intelligence and freedom” and by contributing to the universal destination of material wealth.

“By means of his work man commits himself, not only for his own sake but also for others and with others,” wrote John Paul II. “Each person collaborates in the work of others and for their own good.”

It is important to note that in Pope Leo XIII’s affirmation of private property — and its subsequent reiteration by the Second Vatican Council and by Pope St. John Paul II —the right to it is not absolute. As John Paul II wrote in Centesimus Annus, ownership becomes illegitimate when “it is not utilized or when it serves to impede the work of others, in an effort to gain a profit which is not the result of the overall expansion of work and the wealth of society, but rather is the result of curbing them or of illicit exploitation, speculation or the breaking of solidarity among working people.”

In a nutshell, private ownership is legitimate only to the extent that it serves the common good. If and when this is overlooked, society will fall into the abyss of heartless subjugation of the human person to impersonal, unregulated and cruel market forces in the presumed primacy of profit over human dignity.

The New Leo

Today, in the plan of divine Providence, we have Pope Leo XIV. His choice of name and his choice of May 18, the 134th anniversary of Rerum Novarum, as the day of his installation as Successor of Peter, are of great significance.

He explained his choice of the name “Leo” to the College of Cardinals on May 10 in these words:

Sensing myself called to continue in this same path, I chose to take the name Leo XIV. There are different reasons for this, but mainly because Pope Leo XIII in his historic Encyclical Rerum Novarum addressed the social question in the context of the first great industrial revolution. In our own day, the Church offers to everyone the treasury of her social teaching in response to another industrial revolution and to developments in the field of artificial intelligence that pose new challenges for the defense of human dignity, justice and labor.

This willingness to respond to developments in the field of artificial intelligence is timely, considering how it is used as a tool for the manipulation of public opinion by individuals and by totalitarian despots desperately searching for public acceptance.

But we also see traces of Leo the Great, and his concern for understanding who Jesus truly is, in our new Pope. As Leo XIV said in his first homily as pope, there is a danger of reducing Jesus “to a kind of charismatic leader or superman,” thus denying his divinity. Leo XIV warned that this can even befall baptized Christians, who then end up living a kind of “practical atheism.” At the same time, Leo XIV emphasized at his inauguration Mass the importance of the encounter with Christ, who draws close to us in his humanity.

In just over two weeks as pope, we can see how our New Leo, a son of St. Augustine and an alumnus of the Angelicum, seeks to follow the Leonine legacy of those who came before him — both the First Leo and the Last.

Dominican Father Anthony Akinwale is a theology professor at the Augustine University in Ilara-Epe, Nigeria. In 2023 he received the Dominican Order’s “Master of Sacred Theology” designation.