Even if the world meets its most optimistic climate goals, rising sea levels will likely intensify throughout the 21st century and beyond, reshaping coastlines and threatening hundreds of millions of lives. A new study published in Communications Earth & Environment warns that keeping global warming below 1.5°C, the aspirational target of the 2015 Paris Agreement, will not prevent significant and accelerating ocean encroachment. Drawing on satellite data, paleo-climatic comparisons, and updated projections, the research paints a stark picture: even modest warming levels will trigger feedback loops in the planet’s ice sheets, propelling sea level rise beyond manageable limits.

Oceans Rising Twice as Fast, With No Signs of Slowing Down

Over the past three decades, the pace of sea level rise has doubled—and it’s expected to double again by the year 2100. If current warming trends persist, oceans could be rising by one centimeter per year within just a few generations. “Limiting global warming to 1.5°C would be a major achievement” and avoid many dire climate impacts, said Chris Stokes, lead author of the study and a professor at Durham University in the UK. Yet, he warned, “But even if this target is met, sea level rise is likely to accelerate to rates that are very difficult to adapt to.” With over 230 million people living within a single meter of today’s sea level, and more than a billion within ten meters, even a relatively small increase could lead to catastrophic urban flooding, mass migration, and trillions in economic damages by mid-century.

Ice Sheets at the Edge: Greenland and Antarctica Nearing Tipping Points

One of the most alarming findings of the study concerns the sensitivity of polar ice sheets to even modest warming. According to satellite observations, the Greenland and West Antarctic ice sheets—which together hold enough frozen water to raise sea levels by 65 meters—are melting or calving at a combined rate of 400 billion tonnes per year. These changes are not linear. “We are probably heading for the higher numbers within that range, possibly higher,” said Stokes. He also noted a major shift in scientific understanding: “We used to think that Greenland wouldn’t do anything until the world warmed 3°C,” he said. “Now the consensus for tipping points for Greenland and West Antarctica is about 1.5°C.” This dramatically lowers the threshold at which irreversible ice sheet collapse could begin, locking in centuries of ocean rise even if emissions were curtailed immediately.

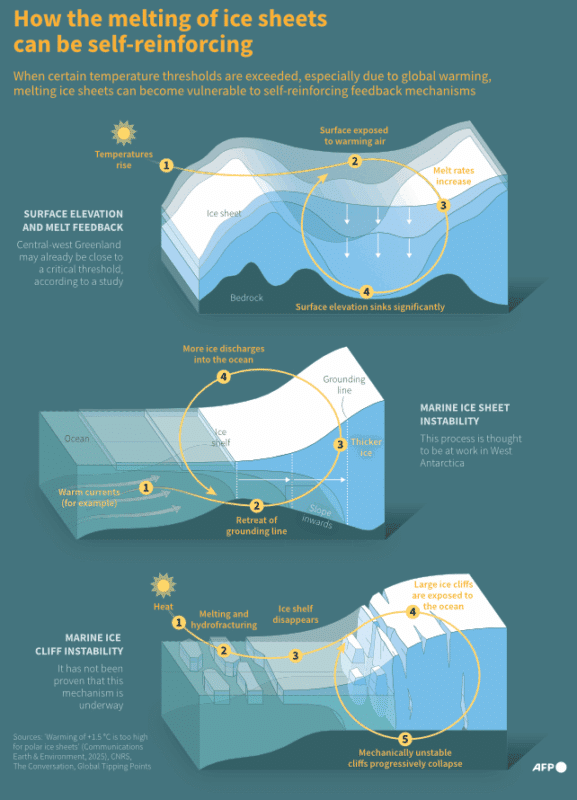

Infographic showing three self-reinforcing feedback mechanisms which can increase the melt rate of ice sheets, as described in the journal Communications Earth & Environment. (AFP/Hervé BOUILLY)

Infographic showing three self-reinforcing feedback mechanisms which can increase the melt rate of ice sheets, as described in the journal Communications Earth & Environment. (AFP/Hervé BOUILLY)

Lessons From Earth’s Ancient Climates Offer Chilling Insights

To assess what lies ahead, scientists also looked to Earth’s climate past, comparing present-day conditions with previous warm periods in geologic history. Around 125,000 years ago, during the last interglacial, sea levels were between 2 to 9 meters higher than today—despite having slightly lower temperatures and significantly less atmospheric CO2. Going further back, roughly three million years ago, when CO2 levels last matched today’s 424 parts per million, seas stood 10 to 20 meters higher. These ancient analogues strongly suggest that current warming has already committed the planet to long-term sea level rise far beyond what is currently visible. This slow but unstoppable process underscores the inertia of the climate system: what seems manageable today could become a crisis in the centuries ahead, even with rapid decarbonization.

A Future That’s Hard to Adapt To Without Drastic Cooling

The implications of this research are deeply unsettling. Without massive investments in coastal defense, the world’s largest cities will face escalating flood risks—regardless of whether humanity holds to the 1.5°C threshold. And long-term adaptation becomes even more challenging when the drivers of sea level rise—such as ice sheet destabilization—are locked in for centuries. As Stokes concluded, “To slow sea level rise from ice sheets to a manageable level requires a long-term temperature goal that is close to +1°C, or possibly lower.” In effect, we may already be on a path that no policy target can reverse, with the only solutions lying in transformative changes to global energy systems, geoengineering, or societal relocation strategies.