We are almost a year into the cycle of interest rate cuts, but it feels harder than ever to say what will come next. One way of looking at it is that cuts have proceeded at a remarkable pace – at least by recent standards. Simon French, chief economist at Panmure Liberum, calculates that over the first three months of the year, a quarter of G20 monetary policy meetings resulted in a cut. Excluding the pandemic, this represents the most sustained pace of nominal cuts since 2008.

But given the low interest rates and low inflation that followed the financial crisis, this isn’t saying much. To give another perspective, the median G20 policy rate is still above 4 per cent – just 0.6 percentage points below the 2023/24 peak. The table below shows that the scope of rate cuts in the US, UK and Eurozone economies this cycle has been limited – especially compared to the steep hikes that preceded them.

There is certainly scope for further cuts, but it is not a case of ‘what goes up must come down’. The Bank of England has said as much itself, warning in May that interest rates were “not on a preset path”, and in February that “rates are unlikely to go back to pre-Covid lows”.

History doesn’t give us much of an indication of where policymakers will choose to stop. The world economy has navigated energy shocks, pandemics and tariffs before – but not in the era of independent central banks. Can economic theory do a better job of telling us how far rate cuts will go?

Read more from Investors’ Chronicle

Where interest rates will go next

Economists like to think of the policy rate as being made up of two ‘parts’. The first is the natural rate of interest that the economy should return to once inflation is back under control. This is the (theoretical) rate of interest that keeps the economy in a state of equilibrium unemployment and on-target inflation. The second part is a ‘cyclical’: the additional tightening or loosening that policymakers sometimes apply to get the economy back on track.

In the UK, today’s 4.25 per cent base rate still has some ‘cyclical’ component. In their latest report, rate-setters said that rates were still “sufficiently restrictive to bear down on inflationary pressures, were they to re-intensify”. They also pointed to further easing, saying that they would take a “gradual and careful approach to the further withdrawal of monetary policy restraint”. Despite the cuts of the past 12 months, the BoE’s rate-setters are still trying to cool inflation (which currently sits at 3.5 per cent) with relatively high interest rates.

As inflation returns to the 2 per cent target (albeit it may not reach this level again until 2027) the Monetary Policy Committee (MPC) will cut interest rates until this ‘cyclical’ component disappears. But thanks to long policy time lags and high levels of uncertainty, rate-setters disagree on how quickly they need to act. In May’s meeting, there was a three-way split: five rate-setters wanted to cut rates this month by a quarter of a percentage point to 4.25 per cent. Two favoured a larger ‘double’ cut, while two voted to maintain the base rate at 4.5 per cent.

There are strong arguments for faster cuts. Though inflation is expected to pick up a little more, the most significant drivers are temporary: annual utility price hikes, tax changes announced in last year’s Budget, and the impact of past energy prices ‘rolling out’ of our annual calculations. Yet some members of the MPC fear that workers and businesses are more sensitive to rising inflation than before – and are likely to greet it with higher wage and price demands, respectively. Hawks also point out that changes in global financial conditions (which lie entirely out of the BoE’s control) meant that market interest rates had eased since the MPC last met.

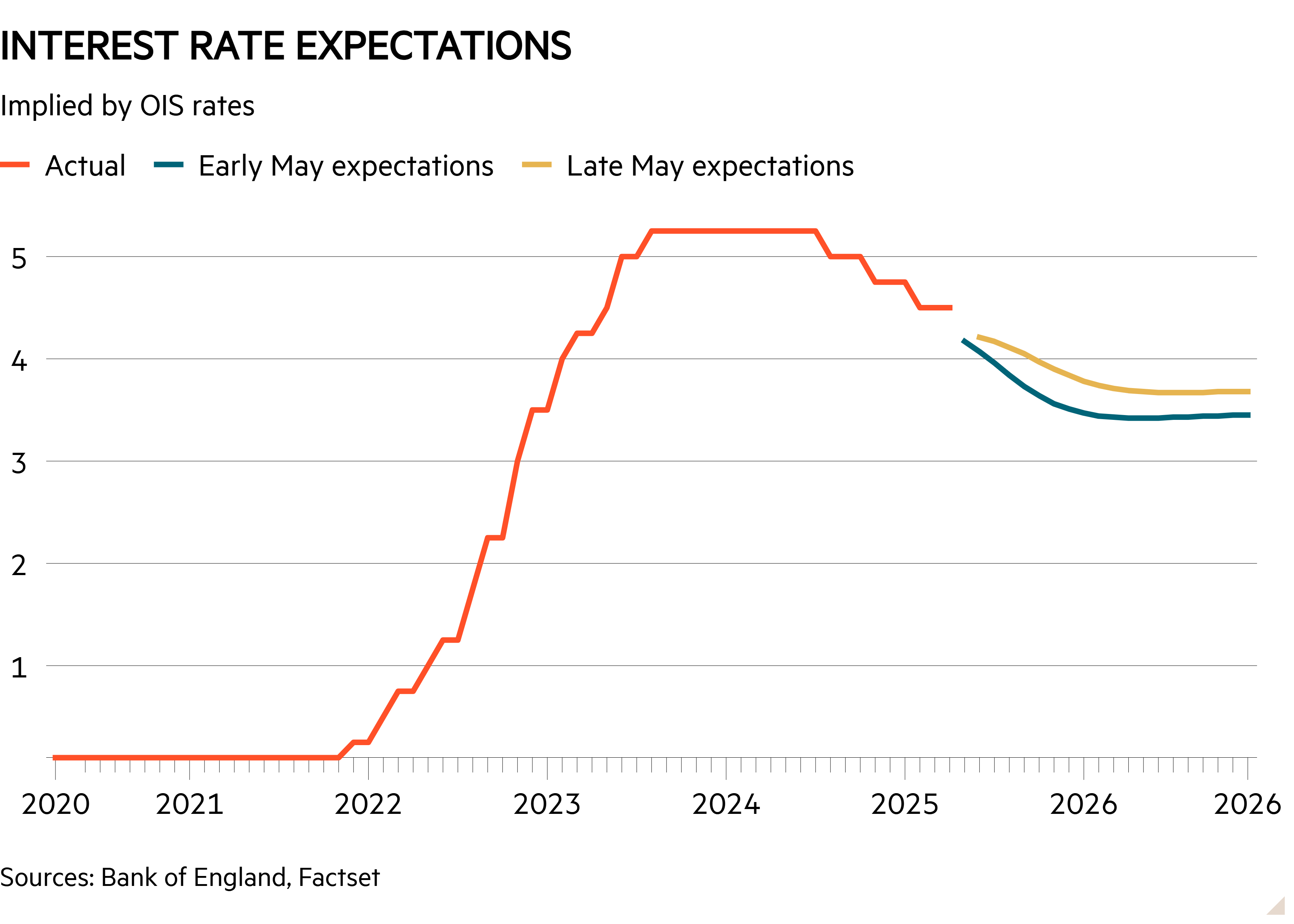

As a result of these mixed signals, market exuberance has started to wane. Before May’s meeting, traders expected interest rates to fall to 3.5 per cent by the end of the year. Today, the figure is closer to 3.85 per cent – implying at least one fewer cuts in 2025, as the chart below shows.

What about the longer term?

Bar any further shocks (and this is a big assumption), today’s inflationary pressure should dissipate over the next 18 months, allowing base rates to return to something closer to their long-run equilibrium. This was generally thought to be around 2-3 per cent in nominal terms, but economists are not so confident any more. Research suggests that the figure for each country is higher than it was before the pandemic hit, and could move further still.

Modelling by economists implies that the interest rate required to keep the UK economy ‘ticking over’ is now about 0.25-0.75 percentage points more than it was in 2018. One driver is higher government debt issuance. This increases the supply of safe assets, putting upward pressure on interest rates. And as the table below shows, economists at the Bank think that financial fragmentation, the rise of artificial intelligence and climate change could all raise the long run equilibrium rate of interest further.

Though this is all theoretical, there are a couple of concrete takeaways. Firstly, even the BoE isn’t quite sure what a ‘normal’ Bank rate will look like after the threat of inflation subsides. Markets expect rates to hover around 3.5-4 per cent over the next five years, and the Office for Budget Responsibility fiscal watchdog sees something similar. Even on-target inflation won’t mean a return to the low interest rates we were used to.