As Lenin famously said, there are decades when nothing happens and then weeks where decades happen – and this feels rather well suited to the European Union right now. Until 2024, the bloc had settled into a familiar narrative: a series of shocks had left the economy mired in stagnation, dragged down by a shrinking Germany.

The threat of US tariffs made the outlook for the bloc even gloomier: the US and the EU are each other’s biggest trading partners – and by a long way. But the EU exports more to the US than it imports, meaning it stands to lose more from a breakdown in the most integrated economic relationship in the world. Tensions over a Ukraine peace deal soured relations further. Upon election last month, German chancellor Friedrich Merz warned that Europe needed to strengthen itself to achieve “independence from the US”.

Europe is shocked into action

But these developments have galvanised the continent, and Merz announced a “whatever it takes”’ approach to ending stagnation in Germany. A coalition agreement could open the door to unlimited borrowing for defence spending, plus a €500bn fund to drive infrastructure investment. This would mark the end of more than two decades of budgetary conservatism, and was described by analysts at Bank of America as a “proper fiscal paradigm shift”. Their forecasts suggest that the German economy could escape stagnation with 1.5-2 per cent GDP growth if the deal goes through.

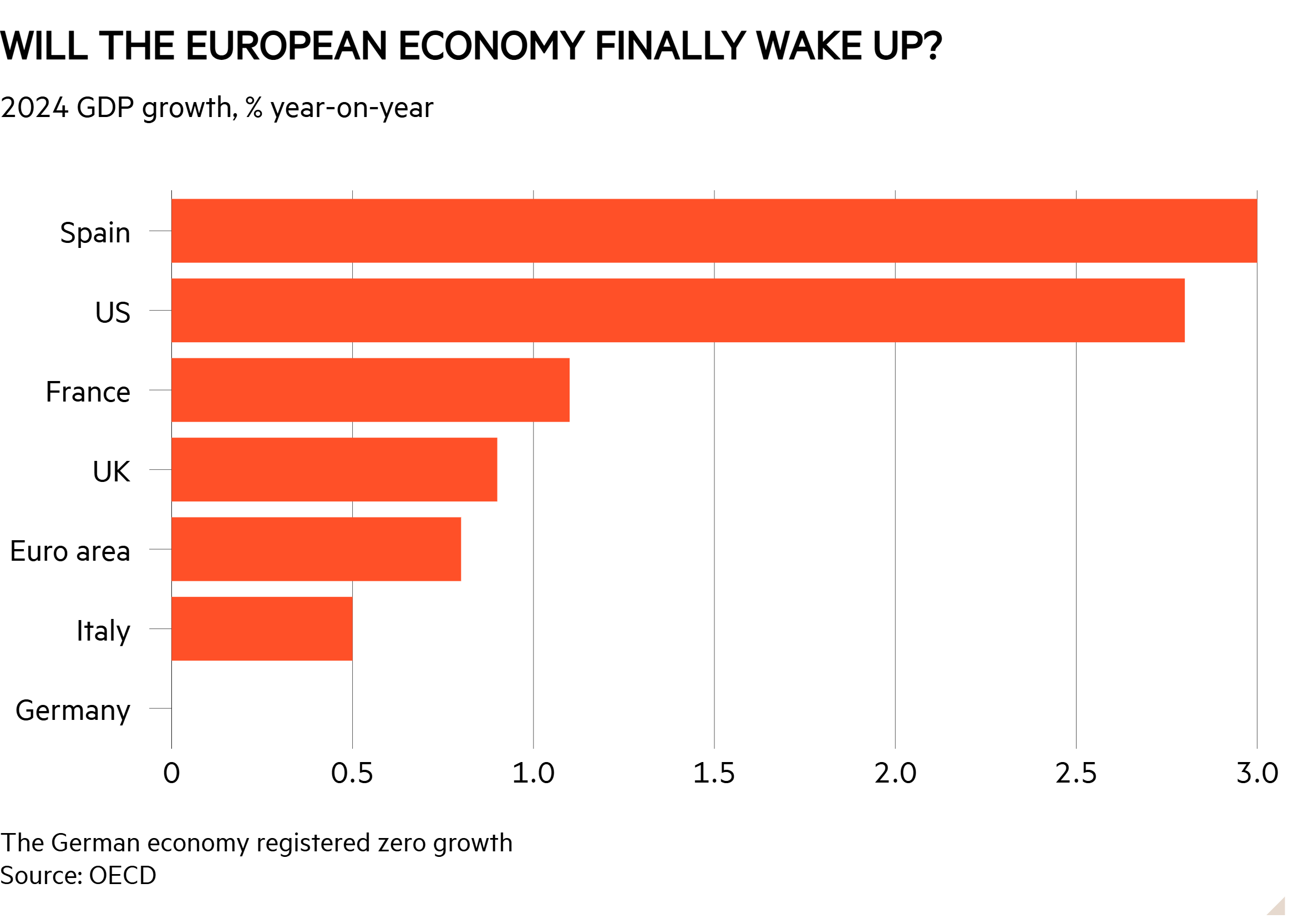

Strained relations with the US are also expected to fuel higher defence spending across the bloc – but don’t expect a debt-fuelled bonanza everywhere. Bank of America analysts think that there will be little “new money” for defence spending, with national budgets making tough sacrifices instead. But this should still be enough to spur growth: their forecasts suggest that the eurozone could easily move from 0.5-1 per cent annual growth to 1-1.5 per cent over the medium term. As the chart below shows, this is a big improvement – and the kind of figures the UK government would love to replicate.

Will the UK move closer to Europe?

Later this month, the UK chancellor will present a pared-back Spring Statement, accompanied by updated forecasts from the Office for Budget Responsibility (OBR). It seems likely that tax rises and tariff-induced uncertainty will mean a gloomier set of growth forecasts from the fiscal watchdog this time around. Capital Economics analysts expect the OBR to cut its growth forecasts from 2 per cent to 0.7 per cent for this year and from 1.8 per cent to 1.7 per cent for 2026.

This (along with an increase in borrowing costs since the Autumn Budget) will make it even harder for chancellor Rachel Reeves to meet her fiscal rules. Forecasters expect her to restore her ‘headroom’ by promising future cuts to welfare and public spending – essentially kicking the can down the road. None of this is particularly promising for economic growth.

By being out of the EU, the UK will at least swerve any US tariffs imposed on the trading bloc’s exports. According to calculations by private bank Berenberg, this should spare the UK economy a 0.5 per cent reduction in long-run GDP. But this isn’t much of a Brexit dividend: studies suggest that the UK economy is around 3.5 per cent smaller than it would have been if it had not left the EU. The EU is still our biggest trading partner, taking 41 per cent of our exports, against 21 per cent for the US. Despite the threat of US tariffs, a closer relationship with the EU could give the UK economy a much-needed boost.

Politically, this seems more feasible than it did a year ago. Labour has pledged to “reset” our relationship with Europe, while YouGov polling suggests 55 per cent of Britons now see leaving the EU as the wrong decision. The government maintains rejoining the single market and customs union are red lines, but Berenberg economists think these could be “watered down” over time. Stronger links between Europe and the UK look a lot more appealing when the US is less of a friend.