Unlock the Editor’s Digest for free

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

The MPC, in its defence, can’t win.

It’s just a few months until the most important event (from FT Alphaville’s perspective at least) of the UK’s monetary policy calendar: when the Bank of England’s Monetary Policy Committee will get together to set the scale of its quantitative tightening operations for the coming year.

QT — the reverse of quantitative easing, under which the BoE is running down its ~£620bn gilt stockpile — is supposed to be a virtually invisible process. As we’ve previously reported, that isn’t the case. In fact, it directly impacts the UK’s fiscal policy as a result of several combined factors.

There’s an interest cost based on the gap between the average return on Asset Purchase Facility holdings (bought when interest rates were low) and the (now-elevated) Bank Rate, which is paid on BoE reserves.

HM Treasury is required to compensate the BoE for any losses that the APF makes.

Having the BoE sell gilts at a substantial pace suppresses prices and increases yields, making it more expensive for the UK to issue debt.

Britain’s fiscal rules are bad, so every quid counts.

There was a time (up until Rachel Reeves’ first Budget, last autumn) when slower QT, or no QT at all, was pretty unambiguously the best option from a fiscal perspective: ending the process would make it cheaper for the UK to borrow and reduce the pressure of the HMT indemnity.

Now, things are slightly different. Because Reeves tweaked the UK’s fiscal rules to focus on current expenditure — and only the interest costs element fall under this — a faster unwind reduces the costs at the latter end of the OBR forecast, creating headroom at the expense of introducing a lot of strain into the gilt market and loading sustained underlying pressure on the public finances.

At present, the OBR expects active sales of £48bn every year until the end of its forecast (2029/30), topping up variable levels of passive reduction via gilts maturing.

And, as we wrote in March, that figure is nonsense: it’s little more than a guess, born out of partial data, crude extrapolation and analytical dereliction.

The actual figure, though, probably won’t be that different this round — even a stopped clock is right twice a day, and the OBR’s time has come.

With £49.1bn in passive sales due in 2025/26, the BoE will, probably, maybe, make £50.9bn in active sales as it aims for another overall envelope of £100bn in QT.

And if it does so, it would be worth a few bob to Reeves, as Borg’s Philip Aldrick and Greg Ritchie wrote last week:

If the bank sticks to the £100 billion run-off, Reeves will be £5.9 billion better off in the Autumn Budget than if it caves in to market pressure and scraps active sales of debt, according to calculations by Jack Meaning, UK chief economist at Barclays, using Office for Budget Responsibility figures.

Meaning found that Reeves would get about £1.6 billion extra headroom under a £100 billion a year run-off, enough to cover the cost of scrapping the cut to winter fuel payments, but lose around £4.3 billion if active sales end.

Alphaville is seeing very mixed opinions about what path the MPC will take. Barclays’ Meaning says “we expect the path of least resistance to be to continue QT at a pace of £100bn”.

Pantheon Macroeconomics reckon that QT’s going fine enough that the MPC won’t want to stop active sales, but do see a slowdown to £80bn in the next year-long window.

TD Securities’ Pooja Kumra sees a possible end to active sales, writing in a February note that:

. . . We doubt that the BoE will need to use active sales when the current bond selling programme ends (Oct24-Sep25). A key risk is from the tightening of financial conditions in the long-end which may need some more caution on the pace of QT.

At lot of this hinges, notionally, on what the “steady state” of Bank of England reserves is, and how soon the MPC expects to get there.

Speaking in April, chief economist Huw Pill raised questions over whether QT pushes up yields when markets are stressed. And, on Monday night, Catherine Mann also stuck her oar in, noting that:

[On] balance sheet normalization, unlike with policy rates, central banks are in uncharted territory. In conjunction with the theoretical derivation and empirical evidence, this has important monetary policy implications as we head into the September decision on next year’s balance sheet run-off, given the indication that we have been moving away from the flat part of the demand curve…

. . . the question for a monetary policymaker is less about the size of the balance sheet than its strategy of normalization, with both remaining stock and flow of assets, and the associated effects on monetary conditions. As discussed above, asset run-off and asset sales can influence monetary transmission by affecting different parts of the yield curve. If large enough, this needs to be incorporated into my future interest rate decisions.

(Uninterestingly, this was the first time we’ve noticed that Mann’s speeches are in American English.)

Vicky Saporta, executive director of the BoE’s Markets Directorate, is due to speak about reserves again next week, which should also be interesting.

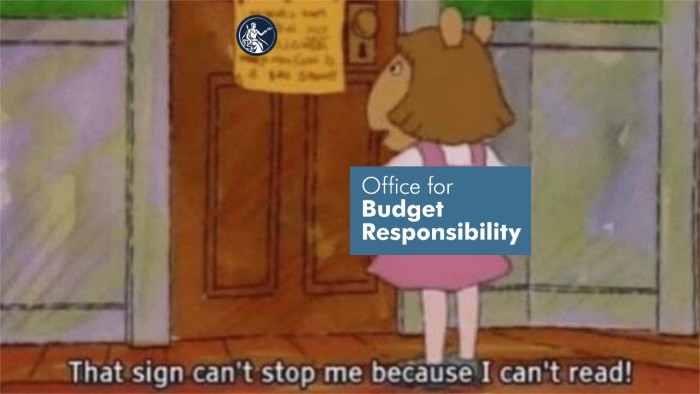

But from a fiscal perspective, there’s a fundamental point that bears repeating (again): none of this matters unless the OBR decides it does.

There’s no way of cleanly estimating future envelope sizes and their associated impacts, and we’re not going to pretend to know what the OBR should do if the MPC decides to pause active sales this year, but we can say one thing for certain: bad projections create risks.

The longer the OBR goes without adapting its process for projecting future active sales, the greater the chance of a forecast-born headroom shock at a future fiscal event. And that doesn’t help anybody.