Pulling a windcheater over his black priest’s attire, Father Ian Wilson walks me up the steep path behind the General Curia headquarters of the Order of Saint Augustine to a secret haven at the foot of the Janiculum Hill that feels a world away from the packed crowds close by in St Peter’s Square.

A spectacular view of St Peter’s basilica appears as Wilson leads me to the spot where Robert Prevost, the newly installed Pope Leo XIV and the Catholic church’s first Augustinian pontiff, once fought his opponents. Their choice of weapons? Tennis rackets.

This was several decades ago, when Wilson, a Scot, and Prevost, a young American, were students here in Rome and the court upon which Prevost shuttled back and forth was just packed earth. Now it’s been upgraded to asphalt. And on Sunday, May 4, while his peers huddled at the Vatican before the conclave and the world debated who would be the new Pope, Cardinal Prevost wasn’t serving a higher purpose — he was serving and volleying against his Peruvian secretary, Father Edgard Iván Rimaycuna Inga.

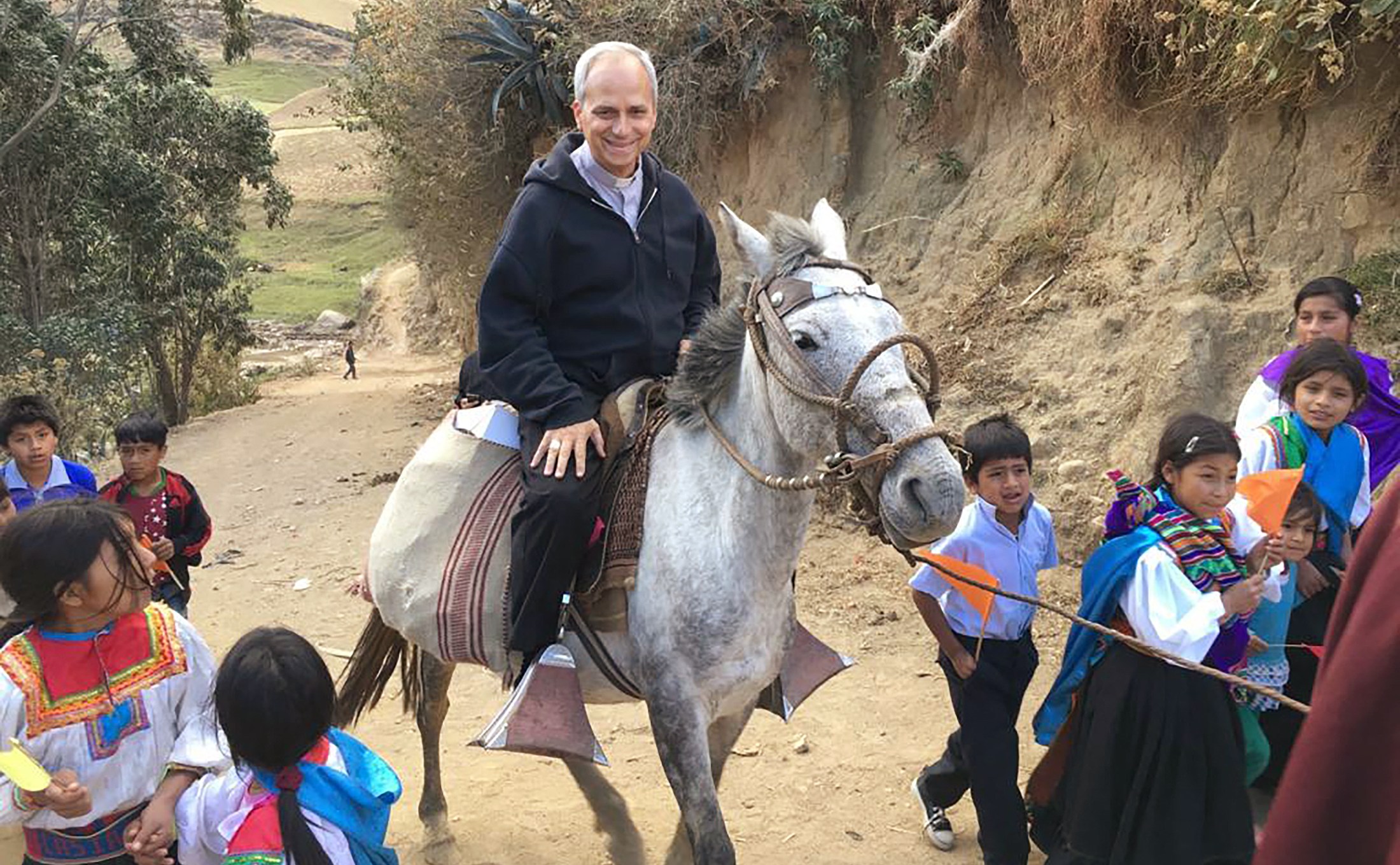

Riding near Incahuasi in the Andes during his eight years as the Bishop of Chiclayo, Peru

GETTY IMAGES

How did the match go? Given that, at 69, Prevost is virtually twice the age of his adversary, you might think divine intervention would have been necessary for him to overcome his opponent. “I don’t know who won,” one member of his order confided to me, then added, “but you always need to let the boss win.”

Perhaps, though, Prevost had no need of grace or favour. In an interview with the website of his Augustinian order a few years ago he said, “I consider myself quite the amateur tennis player,” and according to the Italian sports paper La Gazzetta dello Sport, those who know him say that he has an excellent backhand and is a “formidable competitor”, a trait that has probably been as useful off the court as on it.

A keen sense of humour

Other than his sporting tenacity, what else can his old colleague reveal about the inscrutable missionary priest from Chicago who beat the favourites to be elected Pope in just four rounds of votes, one round fewer than it took his predecessor, Pope Francis?

• Pope Leo is everything Trump is not: a voice for the masses

Wilson, who has a gentle sense of humour himself, says that the new Pope likes a joke. That was apparent on the Monday after his election when a journalist raised the possibility of setting up the Pope and the tennis legend Andre Agassi in a charity match. “As long as you don’t bring Sinner,” the Pope fired back, referring to the world’s top-ranked player.

Sensitive enough to realise that this might be misconstrued as a slight, the Pope later invited Jannik Sinner and his family to the Vatican, whereupon the Italian three-time grand slam champion presented him with a tennis racket and asked, “Shall we play?”

“Here, we’ll break something,” the Pope deadpanned. “Best not.”

His sense of humour aside, Wilson says, “We knew he had the ability to do the job. I was quietly confident because he was never seen as a frontrunner. At the Grand National, the favourites don’t always come home. Sometimes there would be a picture in the press of six papabili [potential candidates for the papacy]. Occasionally he was there, sometimes he wasn’t, and I thought, I’m happy with that. We were quietly hoping.”

Meeting Italy’s world No 1 tennis player, Jannik Sinner, May 14

AP

And when that faith was rewarded?

“I fell on my knees with tears of joy in my eyes.”

It is now clear the bookies dismissed Prevost as an outsider because no American had previously been elected Pope, but failed to notice he had also been a Peruvian citizen for a decade. South America’s cardinals reportedly rallied behind him at the conclave, seeing off a bid to elect the Vatican’s secretary of state, the Italian Pietro Parolin.

“He is the least American of all the American cardinals,” the theologian José Luis Pérez Guadalupe tells me. A former Peruvian interior minister, he has known Prevost for years. “In Rome they call Leo the ‘Latino gringo’.”

That label apart, his politics have been hard to pin down, meaning Catholic conservatives who loathed Francis and progressives who fêted him have all found something to like in Leo.

Speaking to diplomats on May 16, the new Pope defended the dignity of migrants, earning a tick from liberals, while Francis fans also appreciated his talk at the inauguration of how capitalism “exploits the earth’s resources and marginalises the poorest”. Conservatives are meanwhile delighted that a man trained in canon law is at the helm of the church after accusing Francis of making up doctrine as he went along, and they loved hearing Leo tell diplomats the family is “founded upon the stable union between a man and a woman”.

Pope Leo XIV greets the media in the Paul VI audience hall, Vatican City, on May 12

MEGA

Traditional Catholics also cheered when he emerged on the balcony at St Peter’s after his election wearing the classic red papal mozzetta cape used by their hero Pope Benedict, but shunned by Francis. They may hate his decision to push on with Francis’s synods involving laity and women to make the church more collegial, but applaud his opposition to allowing women to become deacons — a proposal that came up at one synod meeting.

“The genius of this election is that Leo offers something of what everyone seemed to hope for in the next Pope,” says Austen Ivereigh, a biographer of Francis and one of the few pundits to predict Leo would be elected.

Childhood friends joked he would grow up to be Pope

Prevost is the first native English-speaking Pope since Adrian, a 12th-century pontiff from Hertfordshire, but his background also reflects America’s melting pot, from the well-to-do New Orleans Creole ancestors on his mother’s side to his father’s Sicilian roots. Raised in a small brick house in a working-class suburb south of Chicago, Prevost heard his mother’s top-notch singing voice as a child and kept up the family tradition with an impressive burst of sung Latin at his inauguration.

When he was a child, his friends joked he would grow up to be Pope when he set up an ironing board as an altar to say pretend Mass while his two older brothers were outside playing cops and robbers.

Middle brother John has stayed close to Robert, reporting they do the online word game Wordle together and revealing his brother told him he watched the film Conclave on the eve of the real conclave.

His eldest brother, Louis, was in bed in his home in Florida when he heard the news. “It’s a good thing I was, because I probably would have fallen over,” he said at the time, adding, “My mind was blown out of this world. It was crazy. So excited.”

Prevost and his brothers Louis, left, and John

ABC NEWS

An outspoken fan of President Trump, Louis got into hot water after the conclave when reporters found he had reposted a video calling Democratic congresswoman Nancy Pelosi a “drunk c***”. Predictably, he got a White House invite from Trump who said, “I want to shake his hand. I want to give him a big hug.”

That puts Louis on the other side of the US political divide from Pope Leo, who criticised the migrant policies launched by Trump and his vice-president, JD Vance, back when he was Cardinal Prevost.

Which may have made for an awkward moment when Vance met the Pope on May 19 at the Vatican, a day after attending the inauguration, although discussions about the Vatican hosting Ukraine peace talks will have offered a useful distraction. Vance presented the Pope with copies of The City of God and On Christian Doctrine, two works by St Augustine, which Vance claims converted him to Catholicism in 2019.

Vance has said The City of God, which describes the debauchery of the crumbling Roman empire, is the “best criticism of our modern age I’d ever read. A society orientated entirely towards consumption and pleasure, spurning duty and virtue.”

It was a clever way to score points with Leo, who has been sprinkling his speeches with quotes by Augustine since his election.

The Augustinian order and a move to Rome

Having graduated in mathematics at Villanova University, an Augustinian college near Philadelphia, Leo joined the Augustinian order and headed for Rome in 1981 to become a priest and study canon law. Arriving in the Italian capital, he lodged at the order’s student residence next to the General Curia headquarters, an imposing complex filled with large, peaceful, airy rooms connected by sliding glass doors and dotted with the dull, solid, utilitarian furniture typical of religious orders.

At the front door, a plaque features the Augustinians’ emblem — a flaming heart with an arrow through it, recalling St Augustine’s famous statement to God: “You’ve pierced my heart with the arrow of your love.”

Born in what is now Algeria in AD354, Augustine initially turned his back on Christianity despite the prayers of his mother, St Monica, before converting and becoming a prolific author of works that have since shaped Christian thinking, including Confessions, deemed the first autobiography. Groups of Italian hermits living by his principles formed the order in the 13th century and today there are about 2,800 Augustinians in 47 countries.

With the late Pope Francis

VATICAN MEDIA

And after being elected Pope, the man who is now the most famous Augustinian joined about 20 fellow members of the order for a lunch of penne carbonara followed by a meat dish, chips and salad. He was in a relaxed mood. “He told us, ‘I will always be an Augustinian,’ ” Wilson says.

Before being given a tour of the General Curia by Wilson, I am ushered into a reception room to talk to Father Alejandro Moral Antón, the tall, softly spoken Spaniard who heads the order. The same age as Leo, he studied with him in Rome and recalls the polite American who played tennis in the garden. “He was very cordial. I remember him saying, ‘Good morning, Alejandro. How are you?’ ”

According to Wilson, there is a community spirit that defined the order back then and still does today. “At the heart of our life as Augustinians is community. We come together for prayer, for worship, for Mass, meals, to socialise in the evenings — maybe just to relax or watch a film on the TV or the news. That’s at the heart of our life. Augustine tells us to be of one heart, one mind, on the way to God.”

Hailing from Hopeman, a small fishing village near Elgin, Wilson, 71, now works at the Rome General Curia as an assistant general to the prior, overseeing the order’s presence in northern Europe.

As he shows me around the neatly kept halls, Wilson says Leo was not the only Augustinian who watched Conclave, recalling how he went with a dozen members of the order to see it in Rome without their dog collars on. “We saw it after a pint in an Irish pub near the cinema. It was great, and to those who don’t like it, I remind them it was a film, not a documentary,” he says with a smile.

When I ask what sets the Augustinians apart from other religious orders, he states that while Franciscans focus on poverty and Dominicans specialise in preaching, Augustinians are all about recreating the early Christian communities “that feel a sense of oneness”.

Prevost made the same point in a 2023 interview. “Having a rich community built on the ability to share with others what happens to us, to be open to others, has been one of the greatest gifts I have been given in this life. The gift of friendship brings us back to Jesus himself. To have the ability to develop authentic friendships in life is beautiful.”

Father Ian Wilson, who studied with Prevost in Rome in the Eighties, at the tennis court where the new Pope still plays

TOM KINGTON

‘A strong empathy with young people’

The future Pope put that lesson to use when he joined the Augustinians’ mission in Peru in 1985. His first stop was Chulucanas, where he and other priests stayed loyal to locals by refusing to flee after a bomb attack on their church during clashes between the government and the Maoist guerilla group Shining Path.

Following a stint in the US, he was back in Peru from 1988 to 1998, running the Augustinians’ seminary in Trujillo, teaching canon law and organising aid for refugees from Venezuela.

“He had a strong empathy with young people. Sometimes he would sit and sing with us — there were people who didn’t think he was a priest,” recalls one local, Juan Carlos Castro. “He was a man who could tell you things clearly and charitably. He could correct you in such a way that you often realised the things you had done, but at the same time you felt this appreciation and love.” Carlos Castro says the future Pope was also a dab hand as a mechanic. “He was always checking cars and sometimes he would fix them, and would fix a computer from time to time.”

A local who was entering the priesthood at the time recalls Prevost arriving at his house in 1996 to drive him to the seminary, helping him load his belongings into the car. “He calmed my mother and father. He was always very fraternal, very close and also understood my parents’ emotions and feelings,” Cesar Eduardo Piscoya Chafloque says.

In endless profiles written about the Pope since his election, his years in Peru are considered crucial to forging his character, but between 2001 and 2013 he returned to Rome, elected twice as prior general of the Augustinians, based at the General Curia, learning Vatican politics and showing he was not just a nice guy.

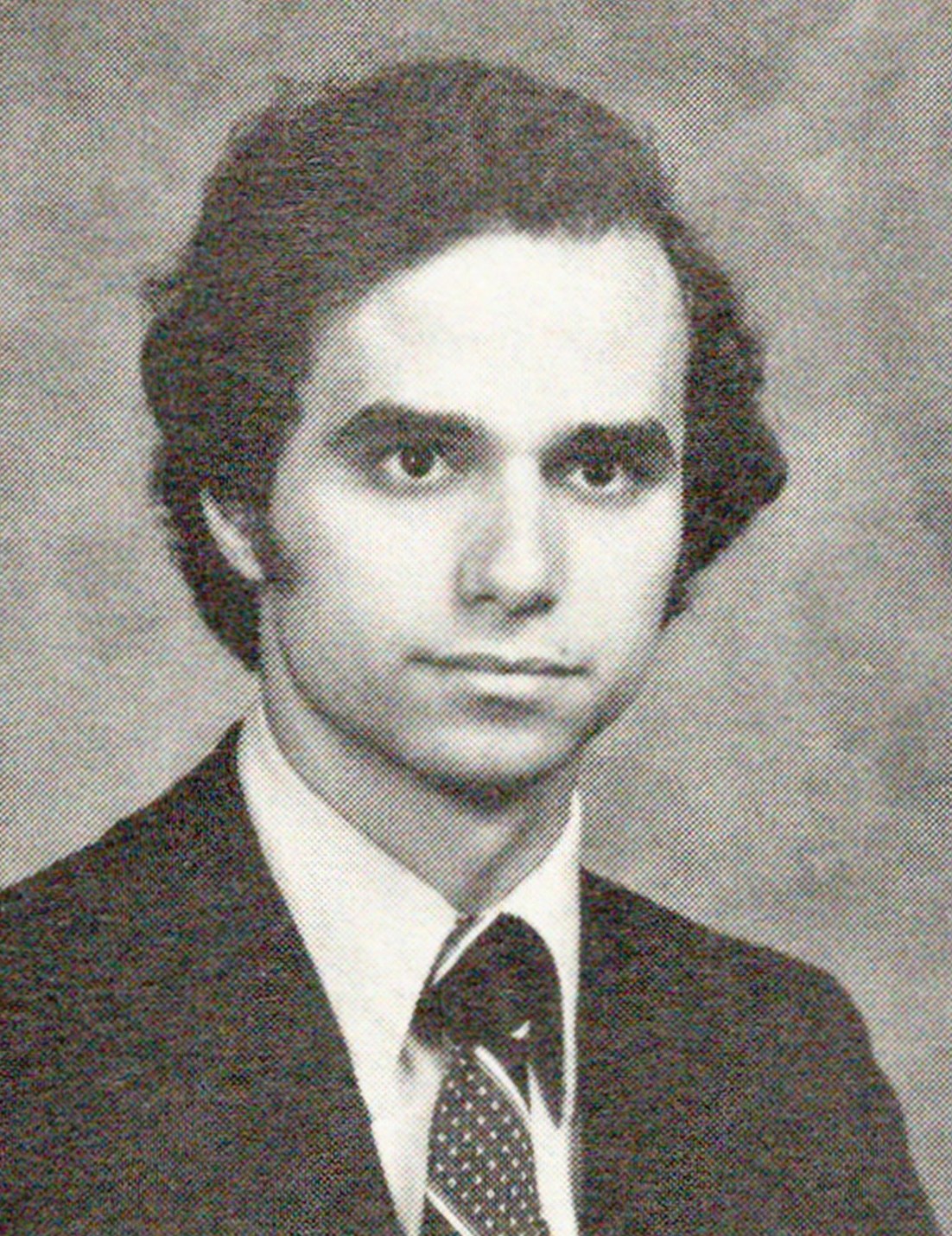

Prevost in his student days at Villanova University in Pennsylvania, 1977

VILLANOVA UNIVERSITY

“He is strong inside. When he decides, he decides,” says Father Moral Antón, who worked under him at the time. The Spanish priest adds that when the voting for a provincial leader was “not transparent”, Prevost would step in and name the leader himself.

In 2013, the Argentinian cardinal Jorge Bergoglio was elected Pope, sparking a turbulent 12 years in Vatican history as Bergoglio — who named himself Pope Francis — focused on caring for the poor and dodging strict doctrine. He also refused to move into the papal apartment overlooking St Peter’s Square, preferring the more democratic charms of the Vatican’s residence for visiting priests.

Francis’s arrival signalled an unexpected swerve in Prevost’s career, which the latter did not see coming. Prevost told his fellow Augustinians in 2013, “Well, thank God, that means I’ll never be made a bishop,” explaining he had not seen eye to eye with Francis and expected his prospects to wane. “Let’s just say that not all our meetings resulted in mutual agreement,” he said.

He was proved wrong, however, as Francis apparently rated him highly — despite or perhaps because of their disagreements — and steadily pushed him up the career ladder, suggesting he was grooming him as a successor.

In 2014, Francis dispatched Prevost back to Peru and appointed him Bishop of Chiclayo, a city of about 1 million people a few hours north of Trujillo.

This time, Prevost was taking over an area run for years by Spanish bishops from Opus Dei, the traditional, tight-knit order. Bishop Prevost soon rang the changes, alleviating poverty by launching job training schemes instead of just preaching and polishing the silverware.

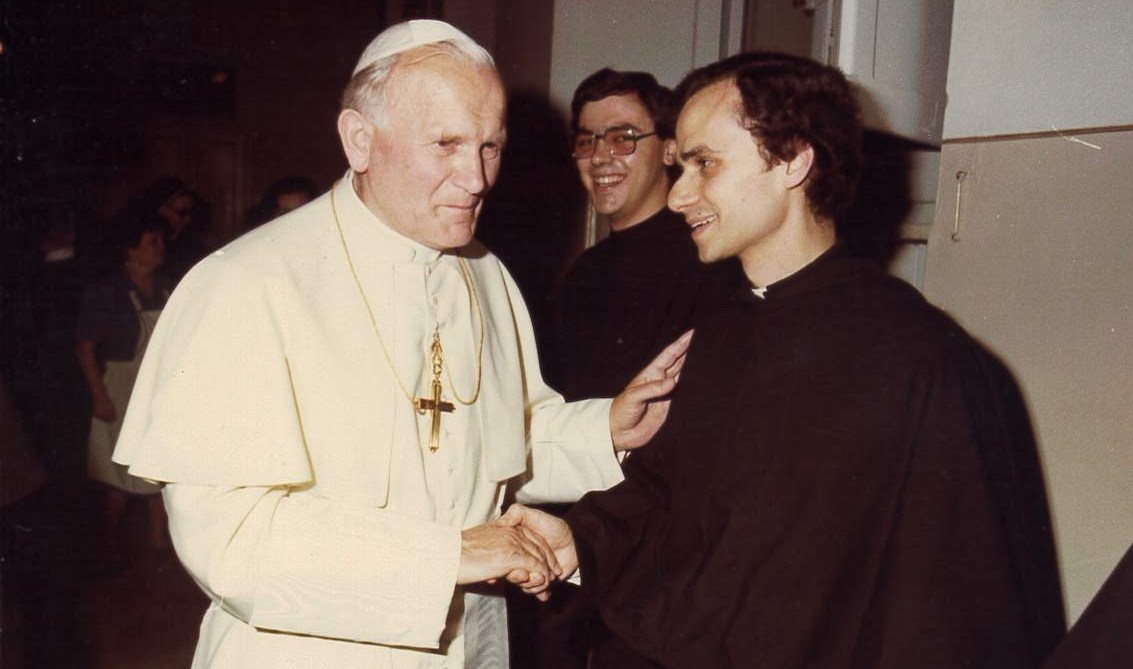

Meeting Pope John Paul II in the early Eighties

EPA

“Prevost was different — an Augustinian missionary gringo with a simple mindset,” Pérez Guadalupe says. “While [the Opus Dei bishops] wore cufflinks and cassocks, he wore black boots and rode on horseback, so logically things changed.”

Instead of fighting the old guard, Prevost won them over. “There was no clash with the Opus Dei clergy, but rather an adaptation to the new times. He gained not only the trust of the people, but also the trust of the other bishops. They saw him as serene, very cautious and very prudent,” Pérez Guadalupe says.

That may change now he is Pope and must decide what to do with the Peruvian Opus Dei cardinal Juan Luis Cipriani Thorne, 81, who showed up at pre-conclave meetings in Rome in his cardinal’s garb despite being under sanction for allegedly abusing a minor, allegations he denies.

‘He wants to walk with the poor and the sidelined’

In Chiclayo, which Prevost said was “only a few letters different to Chicago”, he helped feed the homeless after freak floods destroyed 48,000 homes in northern Peru in 2023. “He was the first to change his shoes for rubber boots — we all got wet, but so did he,” recalls Sister Margarita Flores, a nun who worked in Chiclayo. “We would say that he resembled a small-town priest,” she adds, describing Prevost’s spartan office where he would offer her a glass of water and a simple biscuit.

At a press conference in Chiclayo on the day the pontiff was elected, the city’s bishop, Edinson Edgardo Farfán Córdova, reassured an excitable scrum of reporters that the new papacy would conform to the blueprint created by Pope Francis. “The message is clear: he wants to walk with the poor; he wants to walk with those sidelined,” he said, while positioned beside a framed photograph of Prevost clasping the hand of his predecessor. “Pope Leo will give continuity to everything that Pope Francis has been doing.”

Which is why Prevost took the name Leo. He has said he wants to push on with the work of Leo XIII, the 19th-century Italian Pope who founded the social doctrine of the Catholic church, fighting for decent wages for factory workers and the right to form unions in his 1891 encyclical Rerum Novarum.

In speeches since his election, the priest who once helped to fix computers has become a pontiff who plans to update the campaign mounted by “the Pope of the workers” by taking on the new challenges to “human dignity, justice and labour” arising from artificial intelligence.

With Volodymyr Zelensky, May 18

GETTY IMAGES

That was music to the ears of Paolo Benanti, a Franciscan friar and technology expert who advised Pope Francis and the Italian government on AI. Benanti discussed the subject last year with Prevost, who asked him to give a speech about new technology to bishops at the Vatican.

“He wants to use the social doctrine of the church to make this technology work in favour of the human condition,” Benanti says.

Nigel Vaz, CEO of tech company Publicis Sapient, was invited to the Vatican last month to speak about AI with other business leaders. The next day, the Pope addressed the group. “It was powerful to hear him say he picked the name Leo XIV because Leo XIII was dealing with the Industrial Revolution and addressing the biggest social issues of his time. The Pope said that, today, the church has another revolution happening, driven by AI.”

“His manner, demeanour and style is almost European,” Vaz adds. “His accent is slight. As he spoke, he switched between Italian and English. He’s not someone who is ‘American’ in a classical sense.”

Prevost showed his appetite for fighting injustice back in Peru in 2017. Following the pardon of the former Peruvian president Alberto Fujimori, he urged the notorious strongman to apologise to the victims of his tumultuous reign, which was marred by numerous human rights abuses.

“He said it very calmly,” Pérez Guadalupe recalls. “He has always had his independence and has known to say whatever he had to say.”

That became clear when he went up against the Sodalitium Christianae Vitae (SCV), which has been described as a cult-like Peruvian religious order. Prevost backed two journalists, Pedro Salinas and Paola Ugaz, who were being hounded in the courts by the order after they exposed its alleged sexual abuse of recruits and lucrative business running cemeteries. Ugaz was in Rome for the inauguration and met me in the packed press room at the Vatican. “Prevost raised awareness of our persecution outside Peru with the help of Pope Francis, and asked to meet the victims and provided them with psychologists, medication and money,” she told me.

Leo XIV gives his first Mass, May 9

Prevost could easily have forgotten about Ugaz when Francis summoned him to Rome in 2023 to take over the Vatican’s dicastery, which picks bishops, and made him a cardinal. But Ugaz says that he stayed on top of the SCV case as the order continued to harass her in the courts with accusations of money laundering. “In October 2024, we met Robert in Rome because they continued to persecute us. He said, ‘Don’t worry, we’ll do something.’ He knew they were capable of anything.”

Prevost delivered. In January this year, Francis ordered the dissolution of SCV — but the story is not over. After his election, Leo was himself accused of covering up a case of abuse by priests in Peru. Ugaz denies that a cover-up took place, claiming the SCV is behind the accusations in a bid to smear the man who took them down.

After his election, when the Pope met journalists, Ugaz was in line to give him Peruvian chocolates he loves and a traditional Peruvian scarf.

“He told me to continue our work,” she says. She claims that in all her meetings with Prevost, she never saw him lose his cool. “When he’s faced with injustice, the most you will see is a furrowed brow.”

Arriving at the Vatican in 2023, Prevost faced a new challenge: keeping order at long meetings of 30 or so delegates at the dicastery.

“Everyone had a chance to comment on candidates for bishops,” says the Archbishop of Westminster, Vincent Nichols, a member of the dicastery. “He was very good at giving time to speakers, even those who go on a bit. But he didn’t dress things up or stroke the egos of people. In conversation he gets to the point, does not repeat himself, doesn’t linger.”

When Prevost was asked at the conclave if he accepted the top job and which name he had chosen, Nichols was sitting close by in the Sistine Chapel. “He replied as calmly and clearly as you like,” he says. “This is a Pope with great stability of character and clarity of mind.”

The raw emotion of the occasion did get to the unflappable Pope at his inauguration, however, when he was handed the two symbols of his papacy. He fought back tears as he donned the woollen papal stole and the fisherman’s ring in front of 200,000 onlookers in St Peter’s Square. After slipping on the ring — which recalls St Peter’s profession — Leo lifted his hand to gaze at it, as if to check it was real.

Receiving the Fisherman’s Ring, the papal signet ring, at his inauguration Mass, May 18

GETTY IMAGES

And when he met visitors from Chiclayo at the Vatican, Leo confessed he was still having trouble seeing himself as Pope. “After Pope Francis died, that very beautiful church mechanism of a long tradition of congregations first, and then the conclave, began and I can honestly tell you, it never crossed my mind that what happened would have happened,” he said, adding, “I think that our God of surprises sprang a really big one this time.”

Humble tastes and healthy habits

Standing on the baseline of the General Curia tennis court, you can see the papal apartment in which Francis chose not to live. Before him, Romans would take comfort when its bedroom light was on, knowing the pontiff was in residence.

Wilson tells me that before the conclave he said to Prevost, “If you get the job, I would love you to go back and live in the papal apartment. I told him, ‘I don’t want you to live lavishly, because that is not your style, but I miss the lights being on in that building.’ He plays his cards close to his chest — he didn’t say no or yes.”

Last week, Pope Leo was still living in his Vatican flat, yet to announce if he will move into the large papal apartment.

In 2016, the Italian film director and screenwriter Paolo Sorrentino created a fantastic television series called The Young Pope, which envisaged what might happen were a radical young American to become the head of the Catholic church.

Like the new Pope’s, Pius XIII’s (Jude Law) health regime includes working using a pulley-based weight machine — according to Leo XIV’s gym instructor, the pontiff likes to do four sets of ten pulls with 25kg loaded on each arm. Pius also plays tennis. We know this because at one point he tries to come to terms with his responsibilities and personal grief by thwacking a tennis ball against his papal residency, clad in an ornately embroidered cassock and pellegrina. The real Pope prefers less cumbersome attire and last took to the court in blue shorts and a T-shirt.

Two years ago, he said that since leaving Peru he’d had few occasions to play his favourite sport but was “looking forward to getting back on the court”, then added with a laugh, “Not that this new job has left me much free time for it so far.”

Of course, as the leader of the world’s 1.4 billion Catholics, Pope Leo XIV is now busier than ever, but maybe that’s all the more reason for him to schedule a little downtime on the tennis court. It might seem an unusual pastime for a pontiff, but the roots of tennis are entwined in religion.

As early as the 12th century, monks played a ball game in monasteries of northern France that began with the server issuing a warning to the receiver: “Tenez!” (“Take heed.”)

Leo doesn’t even have to go to the General Curia to play — in the north corner of the Vatican, there’s another tennis court tucked away between the museum and the city wall.

Apparently in the late Seventies the sport was popular among the Swiss Guard, the pontiff’s security unit, before enthusiasm for the game waned. Not that the Pope need worry about finding a hitting partner. He serves God, but he knows a Sinner who would willingly serve to him.

Additional reporting: Iñigo Alexander