Charlotte Gray is a biographer, historian and adjunct research professor at Carleton University.

For the past 30 years, one of my favourite places in Ottawa has been the third-floor Reading Room of the shabby Library and Archives Canada building, next to the Supreme Court of Canada on Wellington Street.

Library and Archives Canada is the federal institution responsible for Canada’s documentary heritage – all significant official documents, plus all Canadian published materials. On research trips to LAC’s building, I have always tried to arrive early in the day in order to secure a seat at one of the wide oak tables close to a big window overlooking the Ottawa River.

At the archives, users may have to wait days or weeks for requested material to arrive.

Justin Tang/The Globe and Mail

When I draw breath from immersing myself in Catharine Parr Traill’s nature notes from the 1840s, or Nellie McClung’s novels, or prime minister William Lyon Mackenzie King’s family correspondence, I gaze out at the swiftly flowing water and imagine 18th-century Indigenous fur traders powering their canoes upstream. Or I watch a winter blizzard enshroud the distant Gatineau hills, and think of Susanna Moodie, a reluctant immigrant in 1832, shivering and lonely in her draughty log cabin. And then I return to the primary sources from which I want to pull a compelling historical narrative about Canada – a country that is increasingly indifferent, if not contemptuous, of its own past.

Over the years, LAC’s Reading Room has gradually emptied – of researchers, of archivists, of librarians. But now the holdings of our national archives (founded as an institution more than 150 years ago) are about to be rocket-blasted into public view.

A vast new architectural masterpiece named Ādisōke (“story-telling” in the Anishinābemowin Algonquin language) is rising in downtown Ottawa, close to the site of the long-promised new hockey rink. When it is completed in 2026, LAC will occupy two-fifths of the building’s 20,100 square metres. The rest of the building will house the main branch of the Ottawa Public Library. LAC will use most of its space to showcase its holdings to a new and expanded audience.

Ādisōke will be a big jolt for an institution that has become an Ottawa backwater. Over the past two decades, LAC’s proposal for a Portrait Gallery was cut, its public programming was killed, grants to local archives across Canada were eliminated and its interlibrary loans program was ended. LAC has grown steadily more understaffed, underfinanced and invisible. These days, it is frequented each year by only 30,000 in-person users – academics, writers, researchers and those who enjoy the company of dusty old papers, reference volumes and every book published in Canada since Confederation.

LAC’s Collection Storage Facility in the east end of Gatineau in November, 2022.

Ashley Fraser/Globe and Mail

The total LAC collection is the fifth-largest heritage collection in the world: it contains, for instance, more than 30 million photographs. Reading Room users wanting to look at books, records, photographs or papers must request them to be brought across the river from one of LAC’s two secure, highly specialized preservation vaults in Gatineau, or from storage buildings elsewhere. They may have to wait days or weeks for requested material (provided it is available) to arrive on Wellington Street. Ādisōke will do little for these users. The new building will be great, but can it reverse the neglect of this country’s written records, or the rapid erosion of knowledge about Canadian history?

LAC’s collection is the fifth-largest heritage collection in the world, spanning books, records, photos and more.

Justin Tang/The Globe and Mail

The threadbare state of LAC’s primary function infuriates scholars who want to consult its holdings. Researchers interested in non-government records (family or literary archives, for instance) find service slow; those wanting official government records find the delays crippling. Stephen Azzi, professor of political management and history at Carleton University, has been waiting for some files he ordered for more than two years. He is currently writing a book on the 1988 federal election, and recently requested the papers of John Turner, who was Opposition leader at the time. He was told that the papers had not yet been reviewed. “It is 37 years since that election, and the files may well be essential for my work. But I probably won’t get to see them before I publish my book.”

Dr. Azzi says that, although Canada’s only female prime minister Kim Campbell left office in 1993, “most of her papers are still closed to researchers. This is the period where there should be books and articles on Campbell and her legacy, but they cannot be written because historians cannot gain access to her papers.” Based in Ottawa, Dr. Azzi makes frequent trips to the LAC building on Wellington Street to follow up on requests, but notes that the Reading Room there is almost empty these days. “If you’re a Ph.D. student and you have one year to do your research, you don’t have the luxury of waiting.”

Patrice Dutil, professor in Toronto Metropolitan University’s Department of Politics and Public Administration, shares Dr. Azzi’s exasperation. “Going to Ottawa to consult archives is now off the table, even for someone from Toronto. Travel is prohibitively expensive, and access is shockingly restricted once you are onsite.”

Although Leslie Weir, the Librarian and Archivist of Canada, talks up LAC’s push to digitize records, she acknowledges that less than 5 per cent of its holdings are online. Most digitization efforts are geared to the needs of genealogy enthusiasts, who pore through service records, census records and passenger lists of immigrant ships to trace family histories. Ms. Weir insists that AI will speed up digitization efforts, but admits that progress is slow. She told me that “right now, we’re in exploration, and we’re doing a series of smaller projects to train the tools.” Meanwhile, scholars outside Ottawa cannot access most records remotely, a frustration that left Dr. Dutil shaking his head when we spoke. “How is it that Sir John A. Macdonald’s papers are not already transcribed and on-line?”

The problem is not unhelpful staff, says Norman Hillmer, Chancellor’s Professor at Carleton University and Slater Scholar at McGill’s Max Bell School. It is Canada’s access to information (ATIP) legislation, which came into effect in 1983. Before that, most government records more than 30 years old were automatically accessible to the public – standard practice in national archives in other countries. Now, Canada has no automatic 30-year rule, and all records, those from long ago as well as those of yesterday, are subject to ATIP’s many restrictions. An army of almost 200 archivists reviews requests – some for several thousand pages – for even the most mundane files. In Dr. Hillmer’s words, “Today, it is the responsibility of researchers to justify their right to know what governments did or were doing, rather than the responsibility of government to put its records and those of its predecessors into the sunlight.”

Nu-Anh Tran, a professor at the University of Connecticut, researches Canada’s involvement with the Geneva accords.Justin Tang/The Globe and Mail

The result, according to Dr. Hillmer, is that “archivists are overwhelmed and the study of Canada’s recent past has become almost impossible. Only the brave go to the national archives any more.” When Dr. Hillmer himself is researching Canada and the Commonwealth, he now prefers to travel to Kew outside London, where U.K. National Archives staff produce their copies of documents within hours.

Ms. Weir has successfully wrested additional funding from the government to speed up ATIP requests, but admits that, without a change in legislation, “It’s an ongoing challenge.” This means a disproportionate share of LAC’s straitened resources is directed to the ATIP tsunami, and as a result, observes Dr. Dutil, “LAC is seriously underservicing its clientele.” One consequence is that the number of postgrads who choose to explore Canadian political and national history is drying up.

Arthur Doughty, the Dominion Archivist and Keeper of the Records in

Ottawa from 1904 to 1935, was knighted for his work preserving Canada’s heritage.

Pittaway Studio/Library and Archives Canada

The current state of our national archives and the frustration of serious researchers is a poignant contrast to the institution’s early days, when a charming, bilingual Englishman called Arthur Doughty decided that his mission was to preserve Canada’s documentary heritage.

Doughty was the Dominion Archivist and Keeper of the Records in Ottawa from 1904 to 1935, and he had an ambitious vision for the institution he headed. He was determined to collect, catalogue and label all the scattered bits of paper – treaties, land agreements, custom tariffs, official and personal correspondence, legislation and proclamations – that told the story of Canada’s evolution as a bilingual nation.

Doughty had big ideas for Canada’s national archives, and was determined to gather every little piece that helped tell the country’s story.Dr. Doughty / Library and Archives Canada

He envisaged a national archive that included both government and private papers so that scholars would be able to write reliable histories rather than (in his words) “a picturesque presentation … in which facts were subordinate to the temper or inclination of the writer.” The government’s role was not to interpret history but to provide documents for study. And this, argued the dapper young enthusiast, would strengthen the dominion that had been established less than four decades earlier. “Nothing will develop patriotism sooner than a love for the past history of the country.”

Doughty initiated an ambitious program of acquisition, commissioned a monumental 23-volume Canada and its provinces, edited several volumes of official documents himself, and also made the Dominion Archives (then housed in a forbidding granite building on Sussex Drive) into an engaging place for young scholars. There were regular get-togethers for the growing profession of historians, and games of tennis on the building’s front lawn.

The Dominion Archives Building on Sussex Street in Ottawa in the early 1920s.Topley Studio / Library and Archives Canada

Doughty was excited by the young Dominion’s past, and his passion for acquisition was not confined to written records. He also acquired artifacts that illustrated significant events, and welcomed visitors to inspect them. General Wolfe’s chair, a detailed model of Quebec City, Indigenous weapons, General Sir Isaac Brock’s uniform, flags, posters, First World War weaponry – they all found their way into Doughty’s domain, and were regularly exhibited.

Doughty argued that better access to Canada’s history would inspire patriotism.Dr. Doughty / Library and Archives Canada

According to Ian Wilson, who was Canada’s chief archivist from 1999 until 2004, and then head of the newly amalgamated Library and Archives until 2009, the Dominion Archives became “the place to see Canadian history.” (Much of Doughty’s collection has been transferred to the Canadian Museum of History, across the Ottawa River from Ādisōke, and to the Canadian War Museum.) Schoolchildren were particularly welcome, and Doughty organized coloured lantern slides for use in classrooms across Canada. He even published a children’s history of the country.

Arthur Doughty is one of the more intriguing historians this country has produced. When Ian Wilson started tracing Doughty’s career for a future biography, he discovered that his predecessor had managed to reinvent himself when he moved to Canada in the mid-1880s.

Doughty in his office.Library and Archives Canada

Within the Ottawa elite, nobody guessed that this well-spoken, well-tailored intellectual was an upholsterer’s son from south London who had wildly exaggerated his credentials. Doughty had spent only a few weeks on a course at Oxford University, but implied he had taken his degree there, and then petitioned a minor American university for an honorary B.A. He was also suspected to have been so eager to acquire family papers that he quietly pocketed them while staying with their owners.

No matter. Over the span of 30 years, Doughty did such a sterling job that he was rewarded with a knighthood in 1935. When he died the following year, his good friend prime minister Mackenzie King commissioned a statue of him to stand in front of the National Archives.

The statue of Sir Arthur Doughty in 1967, behind the Public Archives and National Library Building.Library and Archives Canada

The inscription on its base was a quotation from Doughty: “Of all national assets, archives are the most precious, they are the gift of one generation to another, and the extent of our care of them marks the extent of our civilisation.”

However, successive generations of politicians did not share Sir Arthur’s vision. Preservation of written records sank lower and lower on the list of government priorities. Sir Arthur himself disappeared from public memory; budgets for the archives have been squeezed, then squeezed again; Canadian history is now mined for grievances and dominated by claims and conflicts. In the past 20 years, Canadians have turned their backs on the past, preferring to tear down statues of Sir John A. Macdonald rather than explore his tangled legacy.

And the statue of Sir Arthur Doughty? Banished across the river to LAC’s preservation buildings. There is no room for such an effigy at Ādisōke.

An artist’s rendering of Ādisōke’s interior atrium.

Library and Archives Canada

LAC’s new Reading Room will be housed in a sinuous, five-storey building on Albert Street, at the edge of Lebreton Flats. Designed by Diamond Schmitt Architects and Ottawa-based KWC Architects, its total budget hovers around $334-million, with $136-million covered by LAC. About 1.7 million visitors a year are expected, which would rival the Parliament Buildings and the National Gallery. Leslie Weir hopes that at least half a million of those visitors will head into the LAC quarters and enjoy the chance to discover Canadian history. “I want to engage Canadians in our history from a very young age [particularly because] it’s disappearing from school curricula,” she told me. “And I want to give people newly arrived in Canada opportunities to learn more about the country that they’ve chosen.”

How will LAC use all this shiny, light-filled new space? Near the entrance, some of Canada’s foundational legal documents will be on display – such as major land treaties with First Nations, the British North America Act of 1867, the Indian Act of 1876, the Charter of Rights and Freedoms of 1982 – and visitors will be able to buy replicas of them in a nearby gift shop. In the Family History Centre, a visitor will be able to key in their birth date, then read on a huge screen what was happening on that day: which hockey team was playing, who was the most popular musician, what were the headlines. On the floors above, there will be a “Creator in Residence” program, facilities for dedicated genealogists, exhibitions of long-stored historical photos, portraits, landscape paintings, maps and rare books, and a “Heritage Lounge” where visitors can curl up with a first edition by a Canadian author. An “Indigenous Circular Lodge,” a space shared with the Public Library, will support ceremonies and gatherings, including smudging. In the new “Heritage Workshop,” tourists can type a letter on an old-fashioned typewriter, construct their own family trees or attend beading sessions.

Ādisōke’s Indigenous Circular Lodge in a rendering. The lodge will be shared with the Public Library.

Library and Archives Canada

“We want to give you the feeling that you’ve been dropped into our shared past,” explains Jasmine Bouchard, LAC’s assistant deputy minister of user experience and engagement.

The new LAC Reading Room, catering to LAC’s primary clientele, will occupy only a quarter of LAC’s new space. Gone are the wide oak tables and the view across the Ottawa River. Instead, when I visit to consult documents or books, I will share a small table and gaze out at a 19th-century pumping station and aqueduct.

LAC’s new home in Ādisōke promises to showcase its holdings to a new and expanded audience.LIBRARY AND ARCHIVES CANADA

The technology for access to film, audio and digitized records will be improved, but there is no guarantee that access to official records will be any better. And that will put a crimp on scholarly research – the kind of work that writers of popular history like me use to ensure that we are doing more than producing, in Sir Arthur Doughty’s words, fact-free “picturesque presentations.”

Perhaps Ādisōke will revive Doughty’s dream of an institution that excites today’s Canadians about this country’s past. That is certainly Ms. Weir’s ambition. Maybe she cannot improve service to LAC’s primary clientele, but she is determined to attract into the glossy new building visitors who have no idea what lies in the storage facilities of her 153-year-old institution and little exposure to Canadian history. “We’re going to make them feel welcome, and we’re going to draw them in with an event, an author reading, an interaction, an exhibit.”

Ms. Weir is relentlessly upbeat. Her goal is straightforward: she wants Canadians “to know that LAC exists and to engage with us.” She brushes aside concerns that LAC will be competing with the Canadian Museum of History: “We can do unique things because of the breadth and complexity of our collections that can showcase moments or events or people in a different way.” Yes, she agrees, there are conflicting ways to interpret Canadian history, but insists, “we can start with the original documents, the government records … but we can also reflect our different histories.” Her vision, like that of her predecessor Doughty, seems to be expressly inclusive, without an overt ideology.

Ms. Weir’s hopes for Ādisōke make for a striking contrast to what is happening in Donald Trump’s America. For decades, successive heads of LAC have enviously looked south toward the U.S.’s well-supported National Archives, which attracts more than one million visitors to its monumental building on Pennsylvania Avenue every year, and is one of the most popular tourist sites in Washington. But envy has turned to horror. The National Archives incurred the wrath of Mr. Trump when he was charged with mishandling classified material from his first administration that had been delivered to Mar-a-Lago rather than the Archives. Last February, the President sacked Colleen Shogan, head of the National Archives (although she was not involved in the Mar-a-Lago seizure); now, the institution’s budget is in peril.

At the same time, in late March, Mr. Trump issued an executive order called “Restoring Truth and Sanity to American History.” Insisting that the “objective facts” of American history had been replaced with “a distorted narrative driven by ideology rather than truth,” the executive order was an attack on the Smithsonian, the vast complex of museums in Washington, particularly the National Museum of African American History and Culture. Vice-President J.D. Vance, who sits on the Smithsonian’s board, has been given the job of purging “improper ideology” from the museum sites. The threat of the loss of federal funding hovers over the institution unless it reshapes its exhibits to portray an America where racism and sexism are ignored and trans people don’t exist.

What is going on in Washington appalls Canadian historians like Stephen Azzi. “History is about nuance and understanding,” he told me. “It is not about battles between interpretations. That is so damaging.”

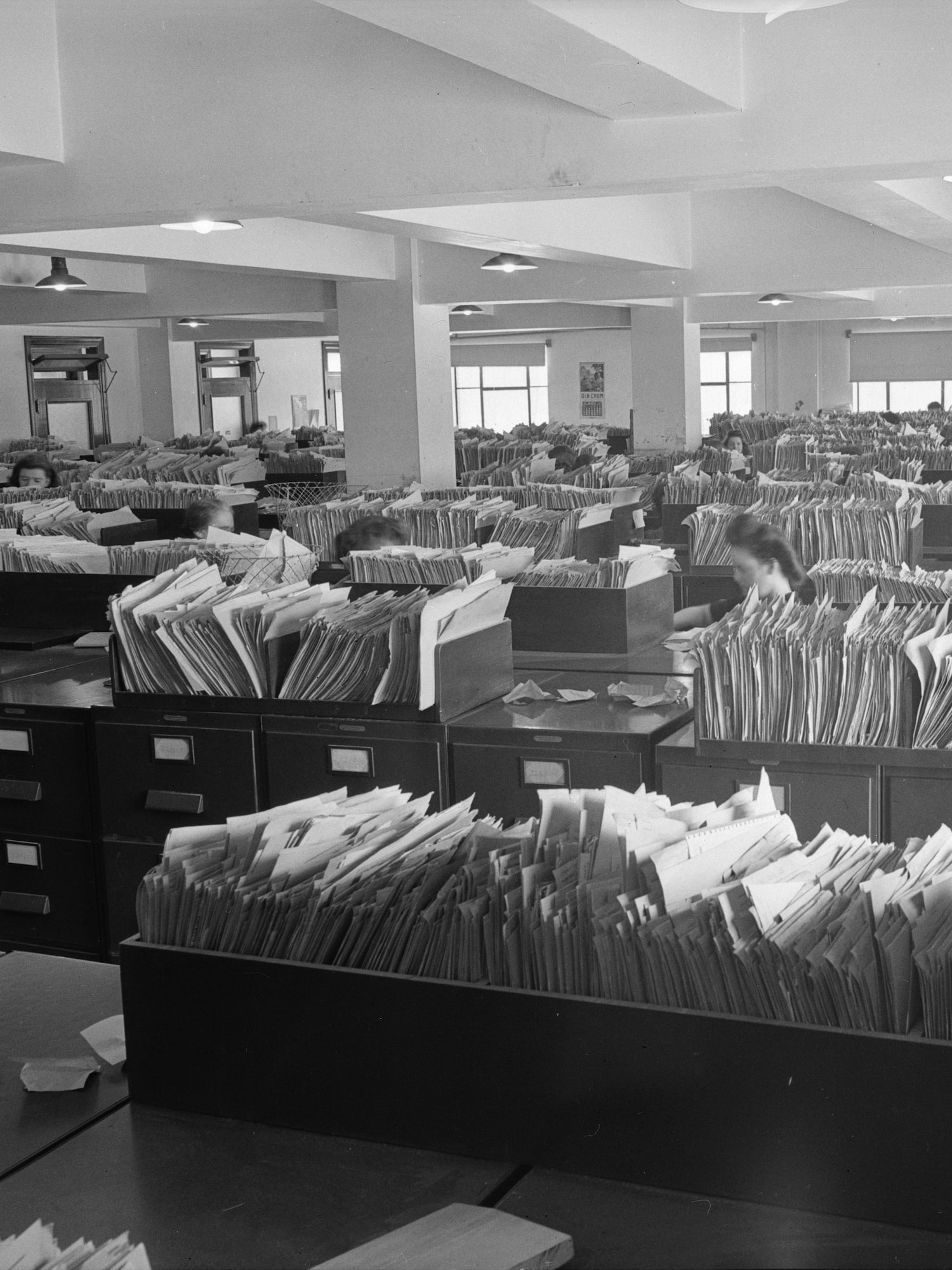

Government employees work behind mountains of paper in the Records and Files Department office of the Central Experimental Farm in Ottawa during the Second World War.

CHRIS LUND/LIBRARY AND ARCHIVES CANADA

The big challenge for the new LAC vision is money, especially while a recession looms. Allowing for inflation, Library and Archives Canada has had no increase in its core funding since 2010 (although there have been supplementary one-off grants – for example, for the construction of Ādisōke, reconciliation-related activities, and improving access to restricted government records) – and it has suffered yet more cuts since then. How will LAC afford all the new programming that Ms. Weir envisages at Ādisōke? She speaks wistfully of “maybe five or six” more staff alongside reimagining current roles and leveraging technologies to expand online access.

However, scholars remain as pessimistic about her plans to reconnect Canadians with our history as they are about her attempts to open up access to research materials. There have been a few imaginative attempts recently to popularize our past, such as Historica’s ongoing series of Heritage Minutes, first seen in 1991; CBC’s 17-part documentary Canada: A People’s History from 2000; the 2017 Broadway hit musical Come from Away; and a handful of best-selling books and graphic novels. But in 2025, Canadian history and biography rarely feature in bestseller lists or popularculture hits.

In the absence of a more concerted effort to explore our past, Canadian history seems destined to slide into oblivion. Perhaps only something truly remarkable – a hip-hop musical about Sir John A. Macdonald by Drake, maybe, or a dystopian movie about the Fort McMurray fire by David Cronenberg – will jerk us out of national amnesia. Perhaps the surge of Canadian nationalism triggered by Donald Trump’s taunts about “the 51st state” will prompt renewed attention to what gives Canada its unique identity. Perhaps the chance to have a hands-on encounter with history in Ādisōke will stimulate interest in what has shaped Canada.

Patrice Dutil is skeptical. “It would be great if it happened,” he says, “but I think it is already too late.”