Three decades after Tokyo subway gas attacks that killed 14 people and injured thousands more, a new book by the head of the police investigation into the Aum Shinrikyō cult looks back on the authorities’ activities before and after the deadly event.

In 2025, Japan marked 30 years since sarin gas attacks on Tokyo subway lines by the religious cult Aum Shinrikyō on March 20, 1995, resulted in 14 deaths and more than 6,000 injuries. Aum leader Asahara Shōkō was arrested in May 1995. The new book Chikatetsu sarin jiken wa naze fusegenakatta no ka (Why Couldn’t the Subway Sarin Attacks Be Prevented?) by Kakimi Takashi looks into police activities surrounding the cult.

At the time of the subway gas attacks, I was a tabloid reporter. In one of my interviews, a police officer who had worked on the investigation into Aum Shinrikyō started by telling me that Aum “beat us to it.” On March 22, the police planned a major raid of an Aum facility in Yamanashi Prefecture. Two days before the raid was scheduled to take place, however, Aum released nerve gas in the Tokyo subway, apparently intending to create a diversion.

Kakimi directed the National Police Agency’s Criminal Affairs Bureau at the time of the attacks, meaning he was the most senior official overseeing the investigation. As he reveals in his book, there were six Aum followers in the ranks of the Tokyo Metropolitan Police, so the possibility that the cult was tipped off on the raid cannot be discounted.

During my interview, the officer mentioned above told me that Aum carried out the subway gas attacks when it learned of the planned police raid, and that the attacks were not foreseeable, and could not therefore have been prevented. I still had doubts, however.

Lab Tests Find Sarin

Kakimi makes a number of revelations in his book. In June 1994, the year before the subway gas attacks, Aum carried out a sarin attack in a residential area of Matsumoto, resulting in seven deaths. After the attack, the Nagano police fixated on a local resident as a key suspect, which held back consideration of other explanations. Meanwhile, a different report was submitted to Kakimi by the director of the Nagano Prefectural Police. In early August, as the investigation progressed, it was found that the list of casualties included a Nagano District Court judge who was adjudicating on a civil suit concerning Aum. The police also learned that an Aum affiliate had purchased chemicals that could be used to manufacture sarin.

It was around this time that the Kanagawa police found a reference to sarin in an Aum newsletter produced before the Matsumoto attack. It was also investigating the disappearance of lawyer and outspoken Aum critic Sakamoto Tsutsumi and his wife and son in October 1989 (all three were later found dead). Kakimi says that it was at this point that the NPA realized just how dangerous Aum was.

When did the police first join the dots between the cult and sarin? At the end of September 1994, the Kanagawa police notified the NPA of a complaint about noxious fumes that had killed vegetation near the Aum facility in Yamanashi.

On October 7, the NPA ordered the Nagano and Yamanashi police forces to jointly collect soil samples for testing. The agency’s forensic laboratory established on November 16 that the samples contained sarin residue.

Police Bound by Rules on Jurisdiction

However, it took a long time for the police to embark on the raid. What happened during this time is discussed in detail in the book. In summary, the police decided that raiding the sarin plant risked endangering the lives of its officers.

Also, while any investigation would require significant resources, at the time, only the Nagano, Yamanashi, and Kanagawa police forces had the jurisdiction to investigate Aum. The NPA wanted to deploy a large number of elite Tokyo police investigators, but no cases related to the cult had taken place within the capital. If the raid was to go ahead, the Defense Agency would also need to provide protective clothing and other support, and the Public Prosecutors Office would need to be consulted.

While the director of the NPA met with other high-ranking officials to discuss the matter, they were unable to set a date for the raid. As deliberations continued, 1994 came to an end. Then, in February 1995, Aum carried out its first attack in Tokyo: the kidnapping and manslaughter of Meguro notary office supervisor Kariya Kiyoshi. This incident led to March 22 being set as the date for the raid, with the kidnapping and manslaughter of Kariya named as the offense on the search warrant.

The book’s testimony is based on NPA investigation records. After the March raid went ahead as planned, the NPA headed an operation to arrest Aum Shinrikyō leaders on a range of charges. The narrative highlights how excess of caution caused the police to be on the back foot. It will also be obvious to readers how the investigation was hindered by its hierarchical nature, in which different prefectural police authorities worked independently without talking to each other.

While the book provides the details, I will say that had the police (who received a tip-off from an Aum follower) been committed to getting to the bottom of the Sakamoto disappearances, they might have been able to stop Aum’s subsequent killing spree. After reading Why Couldn’t the Subway Sarin Attacks Be Prevented? many, like me, will come away wishing that the authorities had gone ahead with the raid when they first understood what was happening in November 1994.

Chikatetsu sarin jiken wa naze fusegenakatta no ka (Why Couldn’t the Subway Gas Attacks be Prevented?)

By Kakimi Takashi

Published by Asahi Shimbun Publications in 2025

ISBN: 978-4-02-252031-9

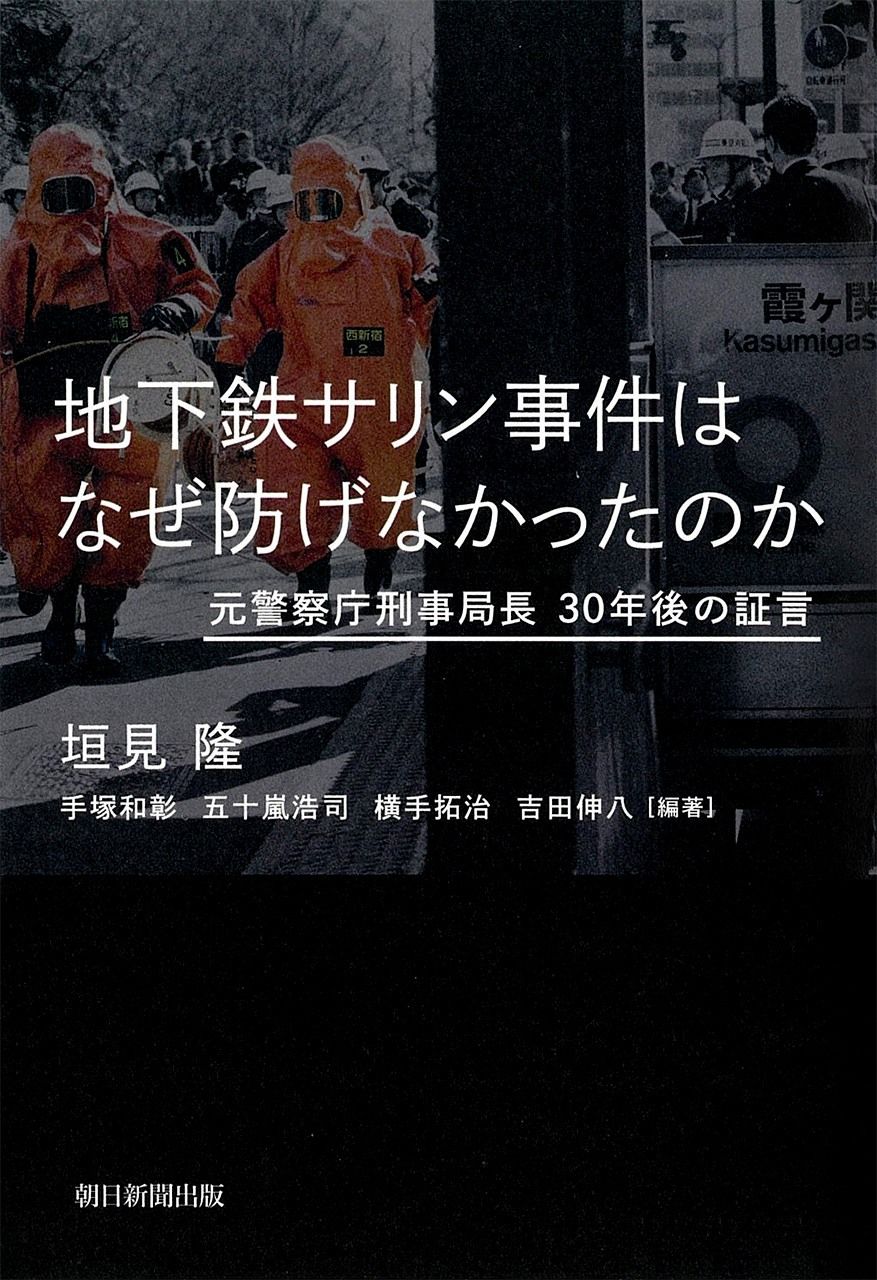

(Originally published in Japanese. Banner photo: A Tokyo Fire Department specialist team in protective clothing prepares to enter Kasumigaseki Station on March 20, 1995. © Kyōdō.)