When you’re standing at the top of the Ledra Palace Hotel, a now-defunct hotel under United Nations (UN) control, you’re in what is known as the buffer zone in Cyprus. On one side of the hotel, Greek flags fly alongside the flag of the Republic of Cyprus. On the other hand, the Turkish flag stands next to a quite similar white and red flag, representing the self-declared Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus. Ledra Palace Hotel, located in Nicosia, Cyprus, the only remaining divided capital in Europe, is one of several sites within the buffer zone where both Greek and Turkish Cypriots come together to engage in bi-communal activities, fostering intercommunal trust and relationship-building under UN auspices. The hotel, which became a focal point for contested control and whose bullet holes from 1974 you can still see, is emblematic of the ‘frozen conflict’ Cyprus remains in.

While the long, ongoing political process continues within the country, more than just high-level political leadership appears to adhere to the status quo. Cultural divisions permeate into school settings, where students remain socially comfortable with their respective Greek or Turkish Cypriot friends. Even within the home, socializing with the other side is not an open conversation. One Greek Cypriot we spoke with said that she learned of her father’s friendships with Turkish Cypriots only after she herself became involved in intercommunal activities, following her university study. But another societal division exists as well, one that is not so visible. There is a divide – between men and women – that is not only evident at the highest levels of representation in the country but also felt by many interviewees, who referenced a well-established history of patriarchal norms and lack of meaningful involvement of women in the political process.

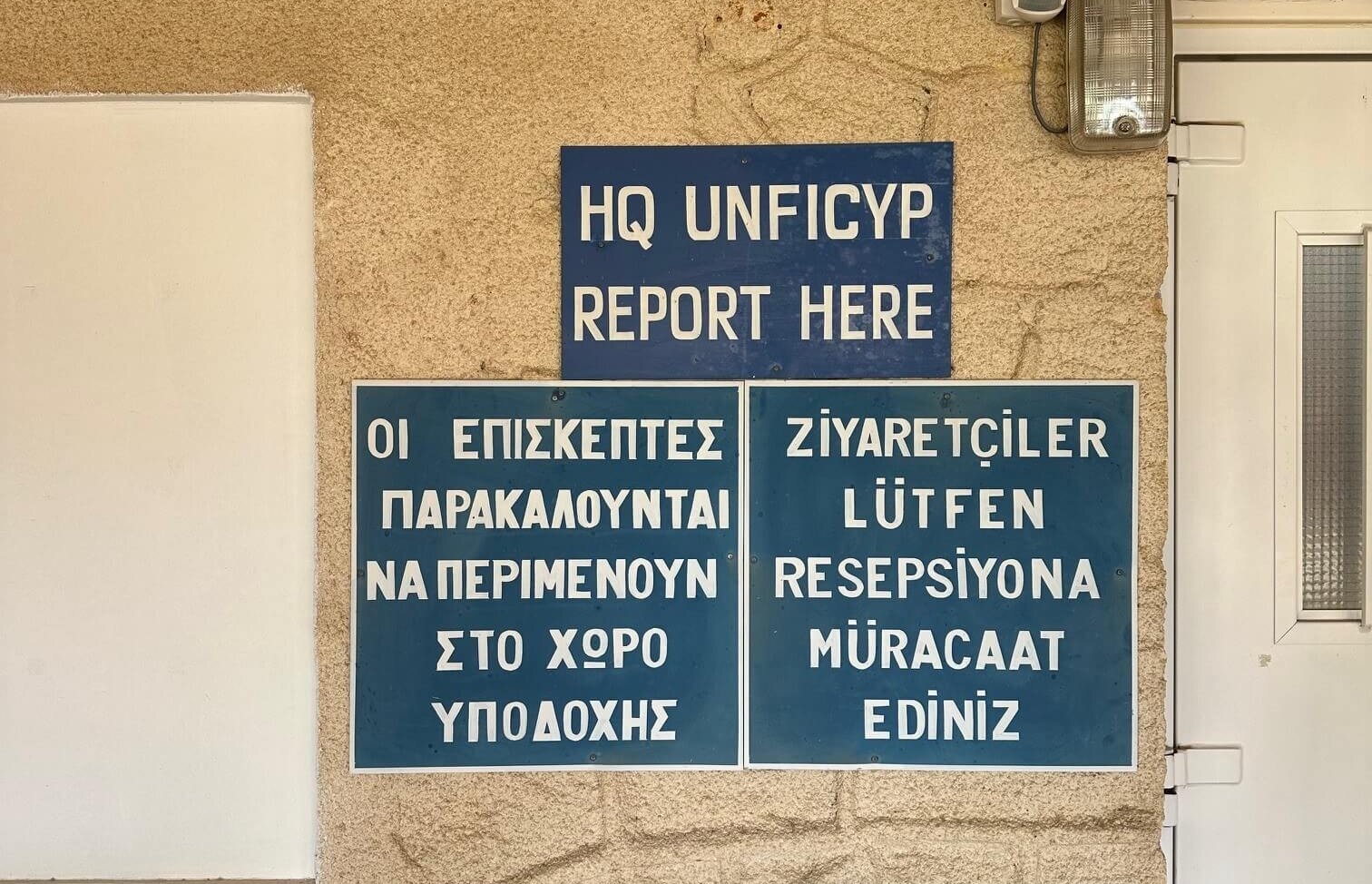

For decades, the United Nations Peacekeeping Force in Cyprus (UNFICYP) has operated in this environment as it implements its mandate from the UN Security Council. As part of its current mandate, military, police, and civilian personnel supervise the ceasefire, monitor the buffer zone, provide humanitarian assistance, and support a political process between the parties on the island through the mission’s civilian leadership. The mission has also been mandated, among other tasks, to support women’s participation in the settlement process, and advance efforts on women, peace and security, including by increasing the number of women serving in UNFICYP, and to take into account gender as part of its mandate.

Together with Lisa Sharland, Director of the Protecting Civilians and Human Security program at Stimson, I traveled to Cyprus seeking to understand how UNFICYP personnel at all levels interpret gender-responsive leadership. This work is part of an ongoing Stimson project.

The mission has been upheld as an example of strong female leadership. In the recent past, all three components of the mission – civilian, military, and police – were headed by women. Yet, our examination of gender-responsive leadership went beyond the inclusion (or appointment) of women into leadership positions. While we engaged civilian, military, and police personnel across the island, as well as civil society representatives and youth, we tried to parse out how the mission navigates its internal mission dynamics at the same time it implements its peacekeeping mandate.

Over the course of a week, we engaged with individuals across the mission – military contingents, UN police officers, senior leadership decision-makers, and advisors. We spoke to representatives from civil society (from both the Greek and Turkish sides of the island) and academics with a robust knowledge of the ‘Cyprus problem’ and UN involvement. We spoke with people in the capital of Nicosia, as well as in all three sectors of UNFICYP operations.

We are currently assessing our research findings from the trip, which will form the basis of a forthcoming Stimson report as part of the ongoing project. However, some things stood out in our preliminary assessments. When it came to discussing mandate implementation (the more visible, external-facing activities), many people spoke of stability, monitoring, and reporting; farming in the buffer zone; illegal construction; migration and asylum seekers; bi-communal activities; and the broader political process. When it came to discussing internal mission procedures, several individuals reflected on hiring practices, women’s representation, a culture of accountability, and the longer-term impact of initiatives focused on gender parity.

On a personal note, the trip to Cyprus was particularly significant, as it was my first field research visit to a peacekeeping mission. When I reflect on the purpose of our visit, I can’t help but notice that the act of my participation in the fieldwork reflected principles of gender-responsiveness. A young, female professional, alongside another female research lead, engaging men and women on their operational effectiveness, mission priorities, decision-making practices, mission culture, and more was an exercise in providing opportunity. The mission – as well as my supervisor – was instrumental in facilitating a gender-responsive research trip. To me, a young woman deciphering UNFICYP’s understanding of its practices as they relate similarly or differently to men and women, allowing space to engage on this topic, and providing a week for a research project of this size is a first step in being gender-responsive.

So, when I think of Ledra Palace Hotel, a site symbolizing island-wide integration and intercommunal ideals, I also think of the status quo it upholds – on either side you see flags representing high-level politics which maintain gender divisions, where there may be women at the table, but without whom negotiations would continue as is. UNFICYP, along with the UN Secretary General’s Good Offices, is working to bridge these divides with the parties to the conflict.

Each person we spoke with had a different understanding of what it means to be gender-responsive, emphasizing the varied degree to which we all understand conflict through a gendered lens. The more aligned we can be on what it means to be gender-responsive and the more we engage on the ways politics and conflict affect men and women differently, the Ledra Palace Hotel stand-in for business-as-usual falls away to the intercommunal understanding it houses within its walls.

The Stimson team is grateful to UNFICYP and the individuals interviewed for their time and engagement on this research. Stimson’s research in Cyprus and the broader project on ‘Framing Gender-Responsive Leadership in UN Peace Operations’ is supported by the Elsie Initiative and Global Affairs Canada. All views reflected in this piece are the responsibility of the author.