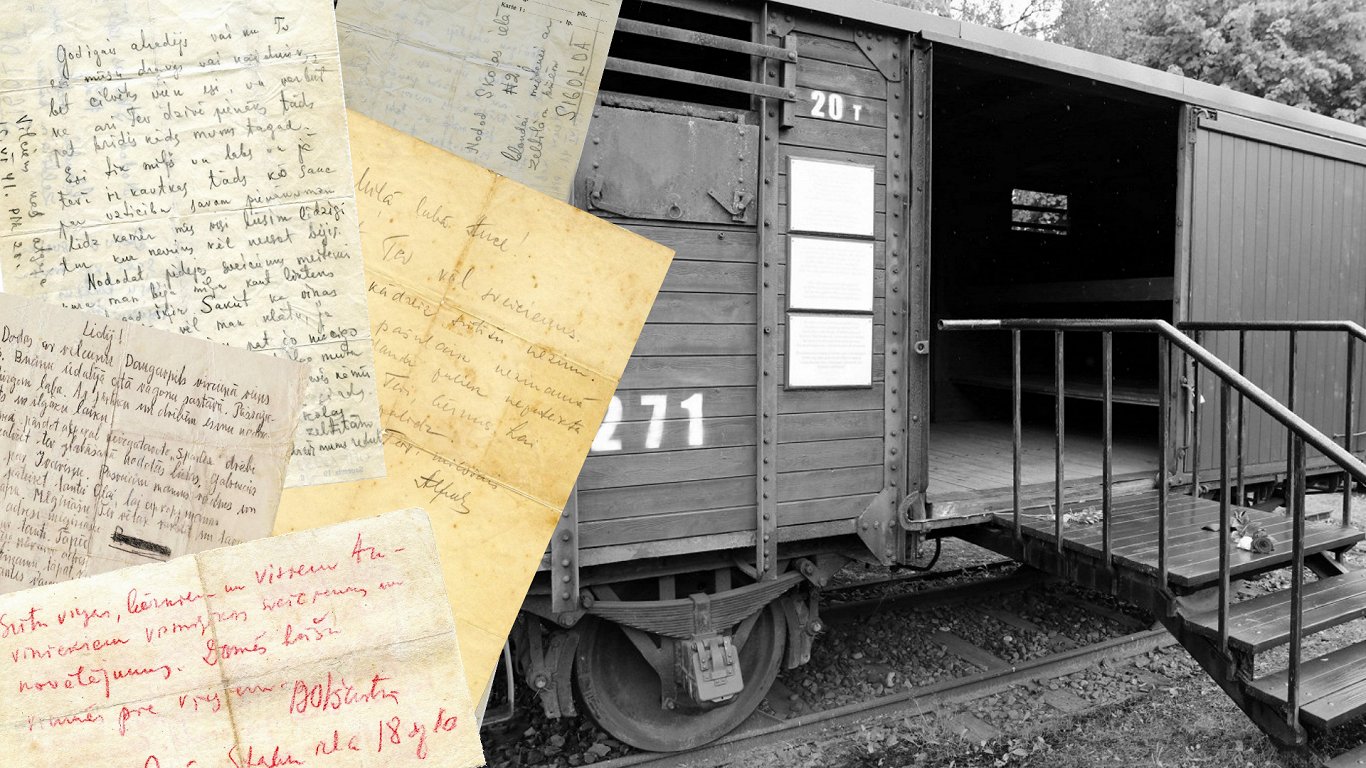

On this day 84 years ago, thousands of people were deported to Siberia by the Soviet occupiers, and many of them never came back.

There were two main waves of deportations, one in the wake of the Soviet Union’s 1940 occupation of independent Latvia, which saw more than 15,000 people (including 2,400 children under the age of ten) loaded into trucks on June 14, 1941.

According to the Museum of the Occupation of Latvia: “Conditions in the hard labor camps were inhumane. The inmates lost their identities, and were terrorized by the guards and criminal prisoners. Food rations were meager, and did not replace the calories expended through work. People grew weak, and were crippled by diarrhoea, scurvy, and other illnesses.

“Winters were marked by unbearable cold, and many did not survive the first one. Only a small part of those deported in 1941 later returned to Latvia. The families in forced settlement had to fend for themselves in harsh conditions; the death rate among the very young and the elderly was likewise high.”

A second wave of deportations on an even larger scale, involving some 42,000 men, women and children took place on 25 March, 1949. Similar actions also took place in Estonia and Lithuania.

So if you see Latvian flags flying with black ribbons attached today, that is why.

At 11:00, in Rīga, in remembrance and honour of the victims of political repression during the communist genocide of 14 June 1941, the Ministry of Foreign Affairs and the Latvian Association of Politically Repressed Persons will hold a commemoration ceremony outside the “History Tactile” Memorial to the Victims of the Soviet Occupation at Latviešu strēlnieku laukums 1.

The event will be attended by senior officials of state and government and members of the foreign diplomatic corps accredited in Latvia.

An excellent multilingual online virtual museum about the experiences of children deported to Siberia can be found here. Another good resource is this interactive map showing exactly who was deported and from where.

President Edgars Rinkēvičs was among officials noting the significance of the date and participating in commemorations. On social media he worite:

“Today the Baltic states mourn victims of June deportations, thousands of innocent men, women and children were deported and killed in 1941 by Stalin and his henchmen. We’ll never forget crimes of the Communist regime.”

Last words to loved ones

The story of the deportees who threw farewell notes from the wagons they were being loaded into was compiled by Latvian Radio on the 80th anniversary of the tragic events of June 14, 1941 – in June 2021, but these stories will never lose their relevance.

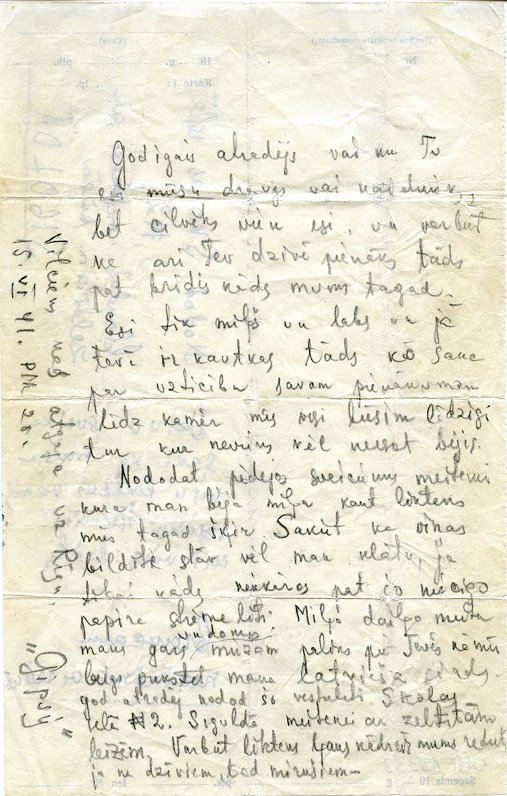

Small, crumpled and hastily written pieces of paper were most likely thrown off the train by the deportees as their trains pulled away. Some of the notes found by those who survived at that time are now kept in the Latvian Occupation Museum.

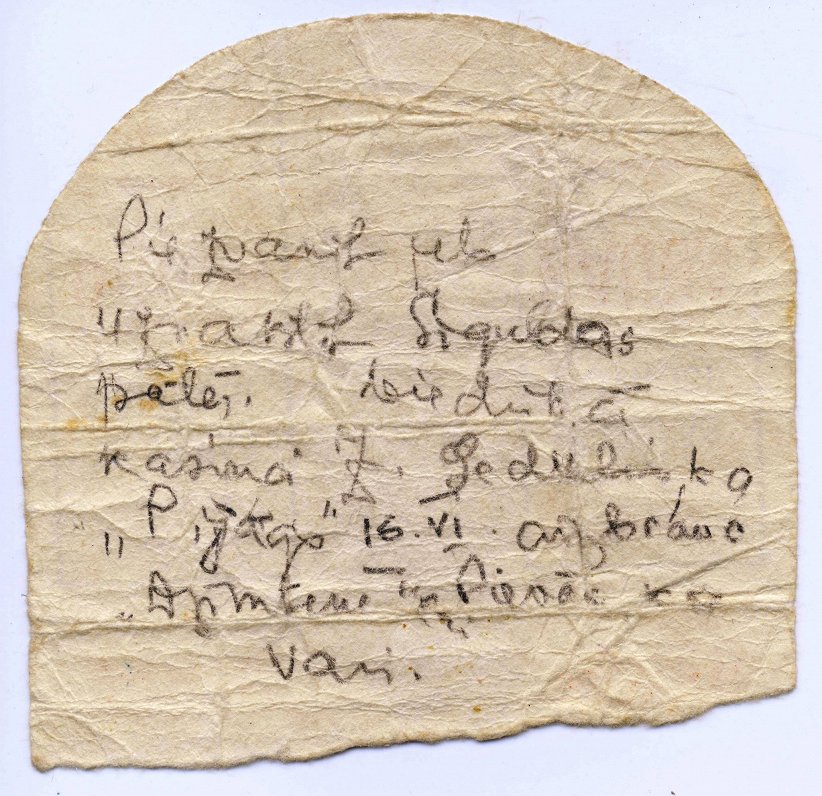

A note written on the crumpled lid of a pack of “Prima” cigarettes from that time was thrown away at Sigulda railway station, asking to pass on a message to the treasurer of the Sigulda Consumers’ Association.

It is unsigned and therefore never reached any addressee. Someone picked it up at Sigulda station, preserved it, and donated it to the Museum of the Occupation of Latvia.

A note by an unknown author, thrown from a carriage during the deportation of June 14, 1941, was found at Sigulda station. Archive photo. Added 15.06.2021. Collection of the Latvian Occupation Museum

Note text:

“Call or write to the cashier at the Sigulda Consumers’ Association (..) that “Pīrāgs” is leaving for “Dzimtene” on June 16th. Bring what you can.”

Pīrāgs (Pie) is most likely the nickname of the author of the note, while he put the word “homeland” in quotation marks, as if ironically referring to the now vast homeland of the USSR.

Father and son

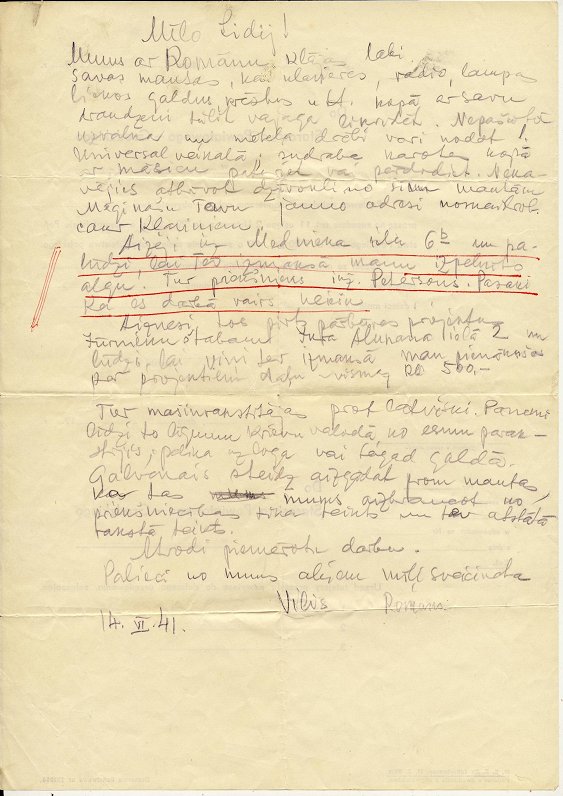

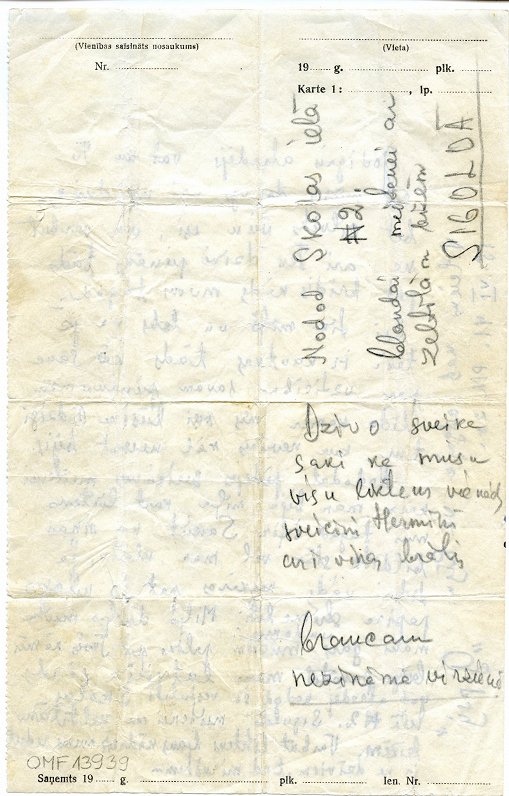

The 47-year-old commander of the Cadet School company, guard Vilis Sniķeris, was arrested and deported from Riga railway station on June 14, 1941. His son Vilis Romans Sniķeris was also deported at the same time. As the wagon trains left the city, the father managed to write and throw away a small note from himself and his son, not knowing that Romans, who was in another wagon train, had also written a letter.

Vilis Sniķeris’ letter to his wife Lidija Jansberga-Sniķeri, written in small letters with a regular pencil, contained various practical instructions on how to proceed.

Letter from deported Vilis Sniķeris to his wife Lidija, dated June 14, 1941. Archive photo. Added 11.06.2021. Collection of the Latvian Occupation Museum

Letter:

“Dear Lidija! Romans and I are doing well, we need to get rid of our belongings, such as the piano, radio, lamps, unnecessary tables, chairs, and so on, together with our maid immediately. You can hand over the unsewn suit and coat to the first department store. Keep the silver spoons with your cousin or sell them. Don’t delay in clearing the apartment of these belongings. I’ll try to find out your new address through Kļaviņi. Go to Mednieku Street 6b and ask them to pay you my well-earned salary. The boss there is engineer Pētersons. Tell him that I won’t be going to work anymore.

Take those bathhouse reconstruction projects to the sailors’ headquarters at Jura Alunāna Street 2 and ask them to pay you the share I’m due for the projects, at least 500 rubles. The typists there know Latvian, take with you the contract in Russian that I signed, it was left on the window or on the table now. The main thing is to hurry and get your belongings away, that’s what the superiors told us when we left and it’s said in the letter they left for you. Find a suitable job. Warm regards from both of us. Vilis and Romans.”

On June 14, 1941, a special meeting of the USSR People’s Commissariat of Internal Affairs extrajudicially arrested Sniķeris for participating in the counter-revolutionary organization “Aizsargi” and convicted him, sentencing him to the maximum penalty – death by shooting.

There is no information about his wife in the deportation case, but the arrest note states that his property should be confiscated.

Sniķeris was imprisoned for about a year in the Usolje correctional labor camp in the Solikamsk district, where prisoners were forced to work in potassium salt mines and in forestry. He was shot in the prison camp on April 6, 1942.

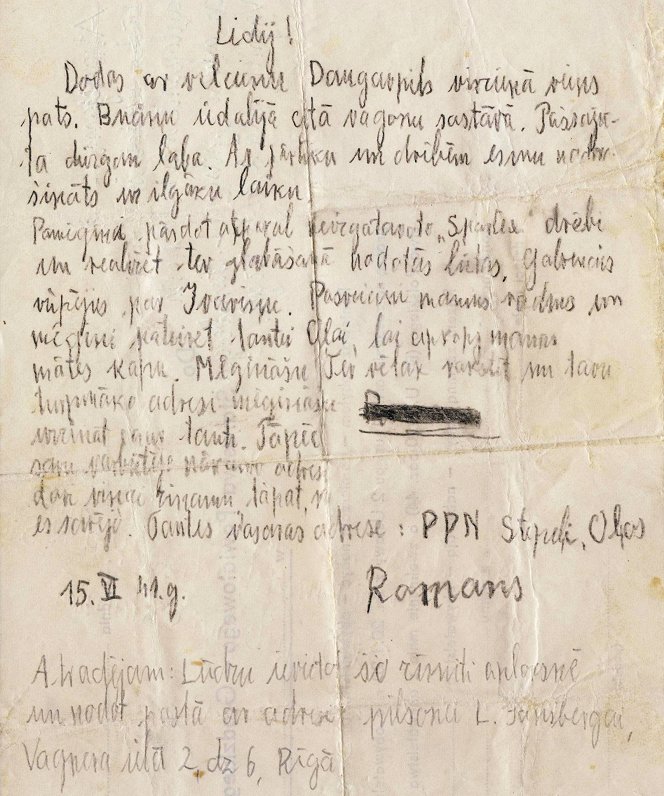

His son, Romans Vilis Sniķeris was only 24 years old when he was deported from Ogre railway station in June 1941. His note is written on the page in clear handwriting with a dark colored regular pencil and addressed to his stepmother.

Letter from deported Romanas Sniķeris to his foster mother Lidija, dated June 14, 1941. Archive photo. Added 11.06.2021. Collection of the Latvian Occupation Museum

Letter:

“Lidija! I’m going by train to Daugavpils alone. Buciņa [father’s nickname?] was assigned to another carriage. I feel quite good. I’m provided with food and clothes for a long time. Try to sell back the unmade … clothes and maybe the things you’ve been given for safekeeping. The main thing is to take care of Ivariņa. Say hello to my relatives and try to tell Aunt Oļa to take care of my mother’s grave. I’ll try to write to you later and I’ll try to find out your future address through your aunt. So let her know your possible future address, just as I’ll tell her mine.

June 15, 1941. Romans.

“To the finder, please place this note in an envelope and deliver it to the post office with the address to citizen L. Jansberga at Vāgnera Street 2, apartment 6, Riga.”

The deportation case of Romans Sniķeris states that he was born in 1917 in Riga, a student. The arrest warrant states that Roman is the son of a former representative of the Latvian Guards and therefore he should be deported from Latvia as a socially dangerous element.

On June 14, 1941, Vilis was illegally deported together with his father, but they were separated – the father was imprisoned in the Solikamsk district, and the son in a camp in the Krasnoyarsk region. On July 21, 1944, Roman died in the village of Karaula, Ust-Yenisei district.

To the girl with gold braids

One of the most poignant such letters was written by Latvian Army Lieutenant Pēteris Leja who was arrested in Litenē on June 14, 1941, and sent to a prison in the Krasnoyarsk region. Before being taken away, Pēteris, then 27, wrote a farewell note to his girlfriend Daila Andersone on a piece of paper.

He wrote on both sides of the page in small letters with a regular pencil and, as he was heading to prison, threw it out of the train.

The outside of the folded piece of paper reads: “Give it to Skolas Street 2, to a blonde girl with golden braids, in Sigulda.” On the outside of the letter, Pēteris addresses a close acquaintance: “Hello, everyone, tell them that our fate is the same, greetings to Hermīne and her brother too. We are going in an unknown direction.”

A note thrown from a train by deported Pēteris Lejas to his girlfriend Daila on June 14, 1941. Archive photo. Added 11.06.2021. Collection of the Latvian Occupation Museum

A note thrown from a train by deported Pēteris Lejas to his friend Daila on June 14, 1941. Archive photo. Added 11.06.2021. Collection of the Latvian Occupation Museum

Letter:

“Honest finder, whether you are our friend or foe, you are only human and perhaps the same moment will come to you in life as we have now. Be so sweet and kind and, if there is something in you called loyalty to your duty, until we are all alike where no one has ever been before. I am giving my last greetings to the girl who was dear to me, although fate now separates us. Tell her that her picture is still with me, even if only this tiny strip of paper. My dear beautiful girl, my spirit and thoughts will remain with you forever, until my Latvian heart stops beating. Honest finder, give this letter to the girl with the golden braids at Skolas Street 2, Sigulda. Perhaps fate will allow us to meet someday – if not alive, then dead.”

Pēteris Leja was born in 1914 in the Kalsnava parish of Madona district. The deportation documents state about Leja: “Secondary education, unmarried, non-partisan, not convicted. Former Latvian army officer. Comes from a family of kulak farmers.” At that time, almost all farmers who owned houses and an independent farm were called kulaks.

The decision of the Special Investigation Department of the People’s Commissariat on his arrest included a detailed statement in the indictment, namely that, in addition to having been in the Latvian army and a kulak, he had a hostile attitude towards the entry of Red Army units and the consolidation of Soviet power in Latvia.

Leja was illegally sentenced to 10 years in prison, and he, like other authors of the last farewell notes, was sent to the Norilsk camp in the Krasnoyarsk region. Leja died in 1942 while imprisoned in the Norilsk camp.

Last words to a family

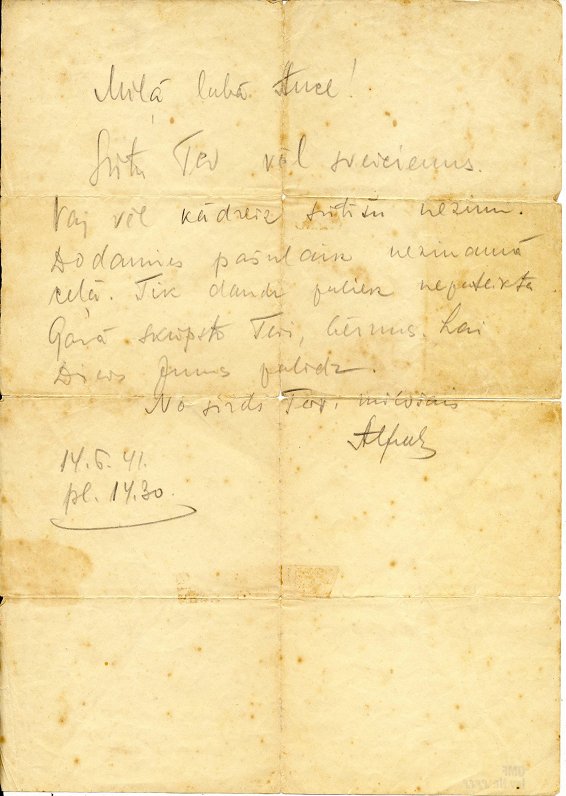

A similarly fond farewell was penned by Latvian Army Colonel Alfreds Platais, who was 44 years old when the Latvian SSR People’s Commissariat of State Security arrested and deported him. Platais managed to write and throw a note from the train to his wife Anna, which reached its addressee. The note was given to the Occupation Museum by his daughter Zigrīda Gintere. The pithy farewell text was written on a now yellowed page in a regular pencil.

Alfreds Platais’ note to his wife Anna thrown from a deportation wagon on June 14, 1941. Archive photo. Added 09.06.2021. Collection of the Latvian Occupation Museum

Note text:

“Dear good Anna! I send you more greetings. I don’t know if I will ever send them again. We are currently embarking on an unknown path. So much remains unsaid. I kiss you in spirit, children. May God help you. Alfred, who loves you with all my heart.”

Alfreds Platais was born in 1897 in Jēkabpils into a family of rural craftsmen. He voluntarily joined the Latvian Army in June 1919 in Riga and participated in the liberation of Latgale. He continued his service after the Freedom Struggles and in the last years of Latvian independence, he was the commander of a company of the Army Headquarters Battalion.

In 1941, Alfreds Platais was arrested and sentenced to eight years in a labour camp. The decision to arrest him, as in all cases of deportees, stated that he was hostile to the Soviet government and engaged in anti-Soviet agitation. He was taken to a prison in Norilsk.

Platais served his sentence, and in 1956 the military tribunal of the Siberian Military District overturned the verdict due to the lack of evidence of the crime and terminated the legal proceedings against Plato. He spent 15 years in Siberia and returned to Latvia, but his family had already fled to Brazil. Alfreds Platais died on July 6, 1979 in Pļaviņas.

There are numerous other examples of such notes in the collection of the Latvian Occupation Museum.