Russians in Istanbul have a very long history. When the political situation or the weather gets a bit rough, our northern neighbors like to descend on Istanbul, or even further south to the Mediterranean coast. Such has been the case since the beginning of the Russia-Ukraine war.

In fact, both nationals have descended on Istanbul in equal numbers, and they have set up a number of cultural institutions in Istanbul: a bookshop, regular fairs for Ukraine, and cafes where poetry and musical nights are held. Many of these events take place in Kadıköy on the Asian part of town and as a student of Russian, I have been trying to follow them.

This summer’s offerings started with a theater show, “Office Romance,” adapted from the famous and very popular 1978 Soviet film, which, I was informed afterward, had started its life as a play in the first place. To book the ticket, I went on a website called “nashbilet” (our ticket) in Russian and saw that after Istanbul, the production would be touring to the southern city of Silifke.

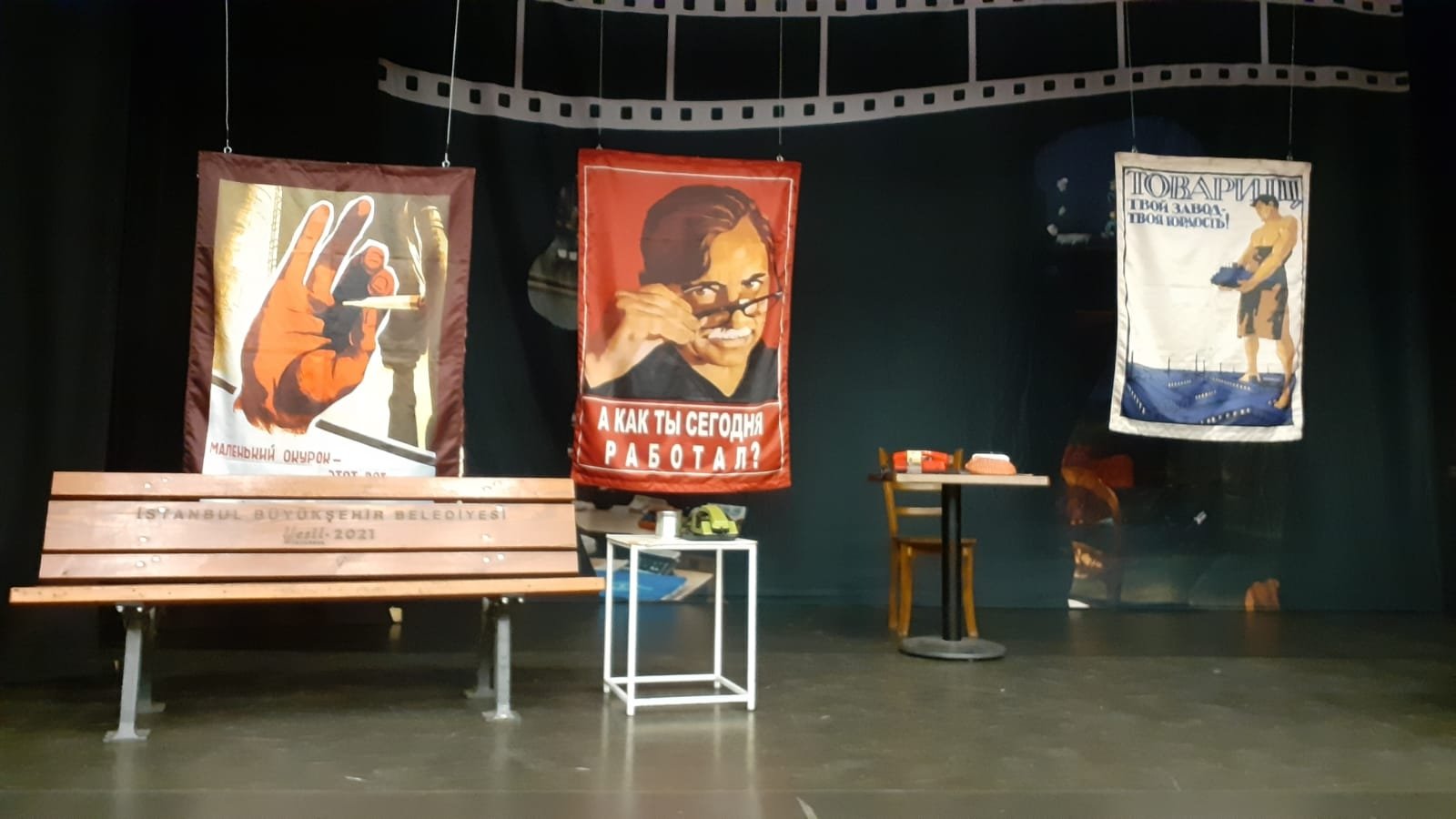

I spent the better part of the pandemic lockdowns watching Soviet films to improve my Russian, and of course, Eldar Ryazanov was the staple. “Office Romance” is one of the favorites, and everyone in the audience (95% Russian women) in Kadıköy had, of course, seen it and had come to laugh and clap at their favorite scenes. “Office Romance” is about an unlikely romance between a civil servant and his boss. The boss is a single woman who is married to her work and dresses “frumpily” while all the others in the office are trying to follow the latest fashion or relax the rules of the workplace. This version sets the scene with few props, most importantly with a Soviet poster that reads “And how have you worked today?” Any production of “Office Romance” will depend on the two lovers, and Ekaterina Simyonava (as Ludmila Prokofievna) and Ilya Alexeev (as Anatoly Yefremovich) carry the characters with great success, leaving the audience in peals of laughter. The story includes an “ugly duckling turns swan” scene, and half the audience gasped at Ludmilla’s transformation. The gist of the “obstacle” in this love story is that Ludmilla can never quite believe Anatoly is in love with her, and there is, I felt, room to explore a new version of this play from that more critical kernel.

An overview of the stage design for “Office Romance,” Istanbul, Türkiye. (Photo by Nagihan Haliloğlu)

The second play of my Russian theater season was in Moscow, where I was on an academic mobility program. I had been in Moscow for a conference in 2008 and then, too, I had seen a play with my nonexistent Russian, the name of which I have long forgotten. But this time I came prepared. My first experience of trying to book tickets online for a Moscow show was that everything was already booked. So with help from a Russianist friend, we sifted through the remaining options and saw that there were tickets for “Petushki” and only after booking the show did I realize that the play, written by Sava Savelyev, was based on the (infamous) Venedict Yerofeyev’s novella “Moscow-Petushki,” about an alcoholic’s “trip” from Moscow to Petushki. As I read the novel in preparation, I remembered I had seen Pavel Pawlikowki’s documentary on the author in my “I have to watch everything Pawlikowski has made” era. I remembered how dark Yerofeyev’s story was, how he had maimed his body with alcohol and how wrong it feels to applaud art that causes the destruction of the artist.

The production I watched seemed to have similar sentiments, because it omitted Yerofeyev’s narrator’s page-long odes to different types of spirits. The novella is one long monologue that is a tour de force of Russian history and culture, but this production divided the narrator’s rambling between three more characters, which, of course, diminishes the effect it has when all these come from one single consciousness. Savelyev has also brought in contemporary props and references like mobile phones and gender references. One of the new characters introduced is an elderly woman who used to be on stage, and she recounts a story in which she cries tears of joy seeing the actor who plays Stalin – to whom I am sure there was no reference in the original novel. She, played by Irina Vibornova, steals the show from the actor who is still nominally representing the narrator and is waiting for the train to go to Petushki to see his son. The most ingenious addition in the production is a small band that plays dark rock songs to relay the emotional landscape of the waiting room.

While booking my tickets online, I had thought one Soviet and one Tsarist Russia play would be fair, and so the second one I chose was Anton Chekhov’s “The Seagull.” Once Google Maps, which goes haywire in Moscow, told me I had arrived at the venue, I spent another 20 minutes trying to locate the theater and even went into a courtyard that looked like it might be a working man’s club. Two middle-aged gentlemen who could easily have played Yerofeyev’s narrator looked at my phone and directed me. I finally found the spot, a basement under a Soviet social housing block. When I went in, the lady at the counter was talking rapidly to the woman in front of me and writing things in an old notebook. What I gathered was that there was going to be another show called something like “The Return of the Soldier” and that the customer could see “The Seagull” at a later date for free. When it was my turn, she repeated the same to me and gave me a kind of theater IOU. I felt I did not have the Russian to understand the answer, should I ask about the cause of the change. I waited for other members of the audience to ask about the cause, but none did, and so it remains a mystery.

The play I was treated to instead of “The Seagull” was indeed about soldiering, in this case during World War II. We started off in an idyllic village where women’s gossip was broken by the voice of Moscow on the radio declaring that the “country is now at war with the fascists.” There were several scenes that reminded me of the current war, one where one of the village women asks where the returning soldier got the fancy silk scarf he has brought her – followed by an uncomfortable silence. The cast gave a very hearty performance, not least when they toasted “Za pabedy!” (To victory!) several times. It was a very intimate space, as you would expect from a Soviet block basement. When one of the soldiers hit a mine (dramatized very cleverly), a woman started crying behind me.

After experiencing the wartime drama in Moscow, I came back to Istanbul and saw another ad for a Russian play on social media. I was a bit frustrated to see it was not a Russian play, but a translation from the English – Nick Payne’s “Constellations.” This time I booked from the usual Turkish webpage, and the performance was in Kadıköy again. This time at my favourite venue, Moda Sahnesi. I read from the Russian translation in preparation and saw that it was a two-actor play, a man and a woman, playing out the same scenes with small differences: a gimmick inspired by the fact that the woman is a particle physicist. This set up naturally meant a lot of repetition, which meant I could follow the play very easily.

The production set my expectations very high as they kept sending messages about being on time throughout the week – what kind of spectacle were they preparing that timing was so important? In the event, the performance started half an hour late, giving me ample opportunity to observe the Russian audience, this time a younger and hipper bunch than for the Soviet comedy. The play started with a “please turn off your mobiles” message in Russian, followed by the same message in English but with a very heavy Russian accent. This was the moment that got the most laughs that evening, as the play goes to some very dark places. When the action finally started on stage, I did a double-take and particle physics did its thing. I was sure the actor I was watching was the Yerofeyev’s narrator in “Pethushki.” As I had not checked the cast for either production, I could not be sure. Back home, I searched online to see that it was Alexander Gorchilin, who, it turned out, I had also seen in the films “The Student” (2016) and “Tchaikovsky’s Wife” (2022).

Of the four, “Constellations” was the best, giving the actors space to explore the various emotions that the couple go through in a parallel version of events.