Telescope ahead and our royal future looks relentlessly white, male, Protestant and privileged. Sigh. If variety is the spice of modern life, then our current King and his two prospective heirs are disappointingly samey. Such is the nature of hereditary monarchy.

Small wonder then, that in an alternative universe our future king has been reimagined in an off-Broadway play as gay. While the title of Jordan Tannahill’s Prince Faggot aims to shock, its title reclaiming the queer smear as a badge of pride – it has sparked a deeper debate around what many think is one of the last taboos embedded in a monarchical system dependent on its ability to sire heirs.

The play – reviewed by The New York Times under the headline, He’s Here, He’s Queer, He’s the Future King of England – imagines the first born of the Prince of Wales (they use a nickname Tips) as gay and in love with a self-proclaimed “brown faggot Dev”. Mum and Dad have long known of their son’s homosexuality; his choice of lover and the public nature of the fallout is what concerns them most.

The play has received rave reviews, but tellingly, there’s no word that the smash-hit will transfer to London’s West End. British discourse, although so often ready to savage the royal family, is also paradoxically protective. There is a spooky historic parallel here, between the international speculation and reporting of Edward VIII’s infatuation with Wallis Simpson everywhere but Britain in 1936 and the current queer air that swirls around ideas of monarchy anywhere but our islands.

Across the globe, teenagers sat agog in front of Netflix’s coming-of-age series Young Royals. A top-10 hit in 12 countries, the drama cast the accidental heir to the Swedish throne as gay. Ultimately, Wilhelm relinquished the crown; the fictional prince’s problem was not his sexuality, but rather the strictures of prospective kingship. How fortunate the real Swedish Royal Family would be accorded more latitude. Months after the series aired in 2021, their government confirmed it would treat the same-sex marriage of a Swedish prince like any other marriage.

Scandinavian countries have long been ahead of the progressive curve; the Netherlands was the first country in the world to legalise gay marriage and likewise claims it would welcome a gay monarch. Britain meanwhile, has not offered an equivalent official pronouncement on a prospective gay king, but our history has produced a litany of royal characters, with a solid root in LGBTQ+ history.

Most famous is perhaps Queen Anne, the last of the Stuarts, who endured 17 pregnancies with no offspring surviving beyond childhood. Queer theory has long been attached to Anne’s tempestuous relationship with Lady Sarah Churchill, the Duchess of Marlborough. The pair had pet names for each other, Mrs Morley and Mrs Freeman respectively, and their letters brim with emotion, indicative of a strength of feeling reflected in the intense animosity of their separation.

Olivia Colman, who played a gay Queen Anne in the 2018 film The Favourite, says that she found it easier to depict the late Stuart monarch than Elizabeth II in The Crown, of whom the actor complained, “everyone knows what she looks like, everyone knows what she sounds like”. Colman’s words are a reminder that if speculation over an 18th-century monarch is fair game, the same cannot be said of contemporary royal players. Look at the stink kicked up over The Crown for daring to create art from the real-life dramas of our royal family. The fallout from gay theatrical japes attached to a preadolescent future king doesn’t bear thinking about.

In Britain, social mores have certainly changed (homosexuality was finally legalised in 1967), but it is unclear by how much, especially in relation to the royal family. This might explain Prince William’s caveat-laden response to hypothetical questions regarding the sexuality of his offspring when visiting the Albert Kennedy Trust, a charity for homeless LGBTQ+ youth, in 2019.

open image in gallery

Netflix’s coming-of-age series ‘Young Royals’ has been a hit with teens around the world (Netflix)

The Prince said he would support “whatever decision” his children made, but added, “It does worry me from a parent’s point of view. How many barriers, hateful words, persecution, all that discrimination that might come, that is the bit that really troubles me.”

How much easier to be a yesteryear monarch when the king could indulge his extra-marital appetite of whatever persuasion, provided there was a suitable royal wife future-proofing the dynasty with the produce of her womb. James VI of Scotland (who was also James I of England) is a fine example of a king whose sexual proclivities behind the scenes were well known.

Diarist Sir John Oglander observed: “The king is wondrous passionate, a lover of his favourites beyond the love of men to women.” James’ fixation with a select few men culminated in his much resented obsession with George Villiers, 1st Duke of Buckingham, the political implications of which played out in the civil wars of this father’s reign. As Oglander noted, James’s loyalty to his “own queen” could not compete with the “great dalliance” he made over “his favourites, especially Buckingham”.

If Stuart monarchs James and Anne are the best known among history’s rich cast of “maybe gay” royals, the list goes on and on.

open image in gallery

Olivia Colman as Queen Anne in ‘The Favourite’ (Fox Searchlight)

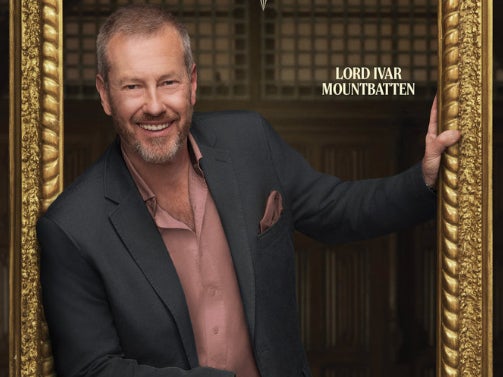

Attitude Magazine had fun flicking through the centuries, plucking out their royal gay icons from Britain and abroad. At home, the nearest our current royal family get to being out and proud is Lord Ivar Mountbatten, the great, great, great-grandson of Queen Victoria, who divorced his wife and married partner James Coyle six years ago. (No royals were present.)

Perhaps predictably, these are considerably more colourful the further back in time you go; needless to say, Little Britain pales in comparison with France’s House of Bourbon. Across the channel, Louis XIV’s brother Philippe, the Duke of Orleans, was encouraged by his mother to cross-dress and never hid his attraction to other men. Like so many of his 17th-century contemporaries, although he married twice and fathered children, a monogamous marriage for love was never on the cards.

In Britain, it was the early-mid 20th century (not an easy time to be gay – with convictions peaking in the 1950s) that rewrote the monarchy’s marital rules. After the First World War saw royal cousins kill royal cousins, George V declared his children no longer had to marry (foreign) royals but could wed British men and women. Dynastic priorities took a back seat to love.

The path was clear for the renamed House of Windsor to inhabit that coveted happy family model Queen Victoria had initiated and Elizabeth II perfected with her pin-up nuclear family. But as the late Queen’s eldest sons would both discover, a national belief in the “companionate marriage” left little wriggle room for affairs – heterosexual or otherwise.

open image in gallery

Philippe, the Duke of Orleans, never hid his attraction to other men (Getty)

In other words, while history’s monarchs could play away in a style of their choice, today’s British sovereigns find their extramarital activities more restricted. For any future king, this model insists on full transparency or a frustrated marriage. Hence, the rich fantasy-land available to playwrights and Netflix dramas. What would happen if a future British king were gay? This becomes an altogether more complex question when you bear in mind the pressure on a royal womb and the line of succession. Whose womb, you well may ask…

Even our more progressive Scandinavian neighbours refused to be drawn over the descendants of a hypothetical gay monarch. The then Dutch prime minister (now head of Nato) Mark Rutte said, “It is not appropriate to anticipate now such a consideration of the succession”. Apparently, the Netherlands will “cross that bridge” when they come to it. Whether surrogacy or adoption, traditionalists can park any anxieties they might have for the moment.

open image in gallery

Lord Ivar Mountbatten, the great, great, great-grandson of Queen Victoria, married his partner James Coyle six years ago (NBC)

So, instead American art has gone where British playwrights fear to tread, cooking up a sumptuous “what if” on the other side of the Atlantic that ultimately has more beef with royalty’s false exceptionalism than the prospective gayness of any future monarch. It is a Transatlantic reminder that the key to hereditary monarchy’s survival is the need to remain relevant.

However, it is worth considering how a gay monarch could serve to broaden The House of Windsor’s base among the younger generation at a time when the uncoupling of the Sussex duo has left the family looking anything but blended.

In the words of their father, Prince William, George and his siblings really can make “whatever decisions” they want to – surely a gentle nod to the progressives amongst us. As Virginia Woolf astutely pointed out in the 1930s, we have an “insatiable need to see” royalty, because “if they live then we live in them too”.

Tessa Dunlop is the author of the new book Lest We Forget: War and Peace in 100 British Monuments