© Shutterstock-Iryna Imago

Lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender people have been celebrating Pride across Europe, but the landscape is divided between national bans and institutional pinkwashing. A look at how the European Union’s work on protecting LGBT+ rights is perceived by civil society

A month full of colour draws to a close. It wasn’t so much the sunshine as the celebration of LGBT+ Pride that made it so vibrant. The annual parades brings a multicoloured crowd to the streets of Europe, committed to fighting for the rights of the lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender communities, as well as other sexual and gender minorities. A non-conformist galaxy, parading its diversity, and often reveling in excess, expressed through colour: queer performers in rainbow-themed sequins and feathers, muscular thirty-somethings in black leather and steel-studded bracelets, elderly bankers who have dyed their hair green and pink for the occasion.

The Pride attendance numbers continue to impress. The largest turnouts have been recorded in New York City with 4 million in 2019, São Paulo with 4 million in 2011 and Madrid with 3.5 million in 2017.

It has been more than fifty years since the parades began rolling through the cities. It all began with the Stonewall Riots of 28 June 1969 in New York City. Following a police raid on a gay bar, riots broke out that led the community to become aware of their rights and make their voices heard. From that point forward, things began to change, and several countries established ad hoc legislation to protect LGBT+ rights. But there is still a long way to go, and sometimes all it takes is crossing a border to find yourself in upside-down land.

Brussels: genuine commitment or pink washing?

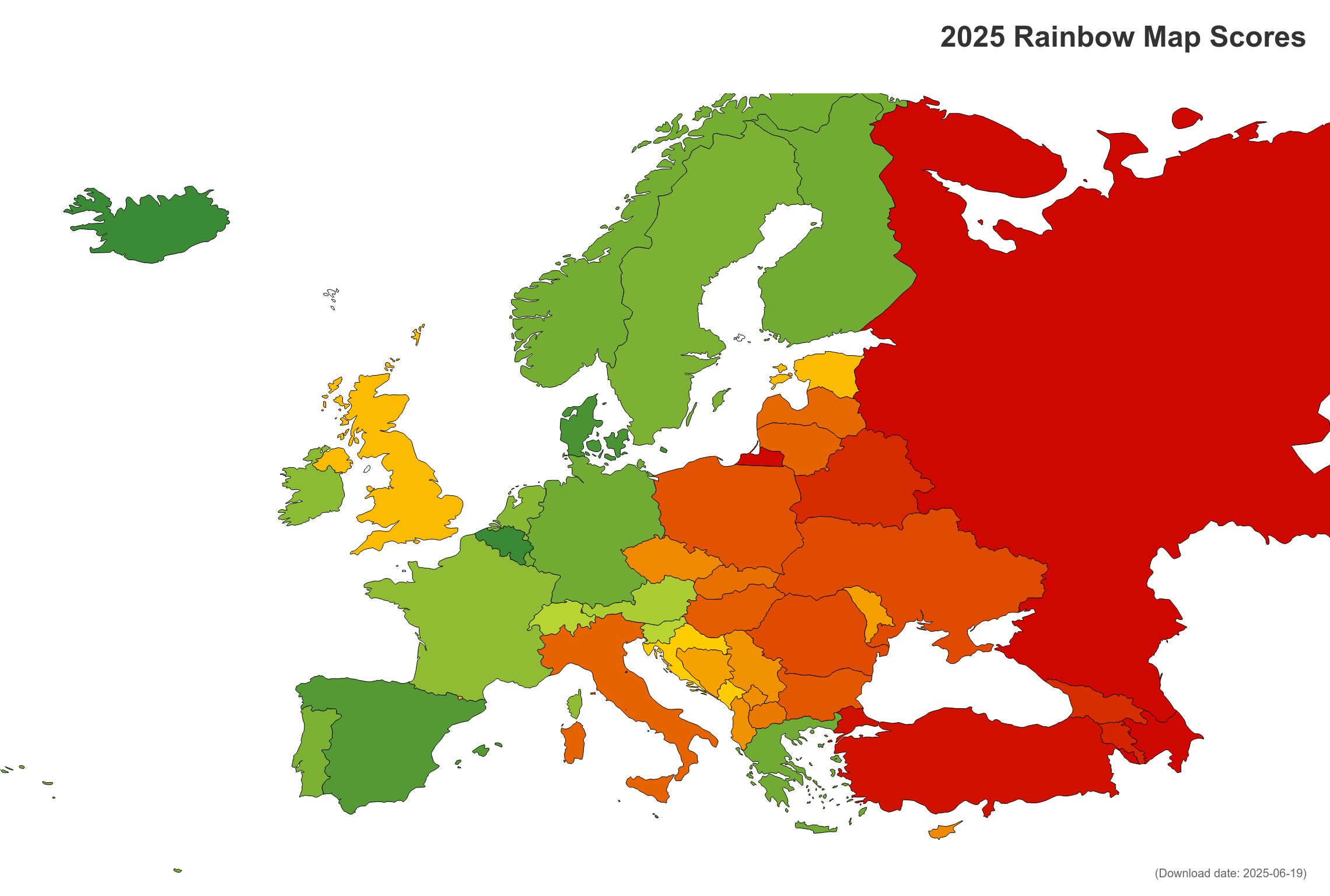

Different countries, different mentalities. ILGA Europe has taken stock of the state of LGBT+ rights across Europe. For about 15 years now, the Brussels-based organisation (which depends on funding from governments, foundations and private donations) has published a report analysing the situation in 49 European states. 76 indicators are used, which are then divided into seven thematic categories: Equality and Non-Discrimination, Family, Hate Crimes & Hate Speech, Legal Gender Recognition, Intersex Bodily Integrity, Civil Society Space, Asylum. Each country was assigned a percentage score (where 100 represents the maximum, the ideal situation, and zero the total absence of rights). Finally, a ranking is drawn up and the results are compiled into an interactive map (the Rainbow Map ) that provides analysis of the positive and negative findings for the LGBT+ community, state by state.

While no country passes with flying colours, many come close. On the other hand, in some areas the inadequacies are extremely serious. The “best” in class is Malta, which scores 88 out of 100 points, and the “worst” is Russia, with two points. Belgium, Denmark and Iceland have done very well, while Turkey, Armenia and Azerbaijan have performed poorly. If we were to draw an imaginary line from the Russian-Finnish border to the Mediterranean via the historic Oder-Neisse line, we would see a continent split in half, with two exceptions: Italy on one side, and Greece on the other. On the left are the “good guys”, on the right the “bad guys”. In other words, legislation in the West is relatively respectful of those whose sexuality “does not conform to the norm”, and in the East it is inadequate, if not non-existent. The legacy of the Iron Curtain still marks certain borders.

In the words of ILGA Europe, “the Rainbow Map 2025 offers a stark snapshot of where Europe stands on LGBTI human rights, and highlights the pressing need to defend and advance these rights in the context of acute democratic erosion”. Yes, a question of democracy. As Chaber, executive director of the Brussels-based organisation, puts it : “we are entering a new era where LGBTI people have become the testing ground for laws that erode democracy itself”.

The division in Europe has also been felt during Pride month. On 26 May, European Commission President Ursula Von der Leyen called on her staff to boycott the next Pride parade in Hungary, scheduled for 28 June. The week before, she had supported the one in Brussels. “Be proud,” she declared on X , with a video showing the rainbow flag flying alongside the EU flag outside the Commission building in Brussels. “Proud of whom you love. Proud of who you are. Proud of who you are becoming. Because your journey is your power. Always remember: Europe is your ally. I am your ally. This week and every week. Be proud. Always”. These diametrically opposed approaches triggered accusations that Von der Leyen was all too willing to set aside LGBT+ rights to avoid provoking Hungarian Prime Minister Viktor Orbán. In March, under the pretext of a 2021 law prohibiting the depiction or promotion of homosexuality to under-18s, the Orbán government effectively banned the 28 June demonstration. As Brussels-based outlet Euractiv satirically put it: “A new EU LGBTIQ equality strategy is due later this year. ‘The Commission is your ally, as long as politically convenient,’ the preface will presumably read.”

According to Manon Aubry, co-chair of The Left group and vocal supporter of the petition to ban sexual conversion practices in the EU, the European Commission “is doing more pinkwashing than taking real action in support of LGBTI+ communities”.

Despite the bans, tensions and political friction, the mayor of Budapest, Gergely Karacsony, has assured everyone that Budapest Pride will go ahead. While doing so, he invoked the democratic tradition of his city. The event will be supported by activists, politicians and institutions. The leader of the Italian Democratic Party, Elly Schlein, as well as the Vice-President of the Belgian Parliament Lotte Stoops and fellow MEP Kimberly van Sparrentak have all promised to attend.

How to safeguard rights: education, education, education

But beyond Pride, what do the activists think? How do they perceive the role of European institutions? Is enough being done to promote a culture of diversity? What forms of hostility do communities experience on a daily basis? And by what means should these adversities be overcome?

In order to gain a better understanding, OBCT, with the help of the independent media network PULSE , interviewed activists and experts from five EU countries: Austria, Belgium, Greece, Poland, Spain.

The picture that emerges is ambiguous. In general, the institutions in Brussels are seen as allies, bodies that go out of their way to recognise the rights of the most vulnerable groups. Dig a little deeper, however, and more than a few doubts emerge.

“The European Union’s policies,” says Óscar Rodríguez Fernández of Spain’s FELGTBI+ , “have led to significant progress in the recognition and protection of LGBTI+ people’s rights, especially in terms of legislative frameworks, projects such as the LGBTIQ Equality Strategy 2020-2025 and the funding for social and educational programmes. However, their actual effectiveness varies greatly from country to country. In many member states, especially those with governments openly hostile to diversity, such as Hungary, Italy or Bulgaria, these policies are ignored. The EU, in particular the European Commission, has a significant opportunity to determine the direction of its LGBTI+ policies in the short term through the LGBTIQ Equality Strategy 2026-2030”.

From Greece, the organisation ORLANDO LGBT does not mince words. They complain that “the privileges that the EU can offer are mainly the prerogative of white, heteronormative and cisgender individuals, belonging to the middle or upper-middle class: access to education, health care, class mobility and even citizenship. This differentiation hides behind the image of a multicultural and diverse Europe, which is far from the reality. The more official European policies pretend not to see the gap between the two, the more fertile ground there will be for authoritarianism, discrimination and the far right”.

Given these ambiguities, the question naturally arises: do the associations feel heard by the officials in Brussels? Fédération Prisme in Liège, Belgium, has some doubts: “Sometimes we feel more ‘recognised’ than genuinely ‘listened to’. Although institutional recognition exists, it remains somewhat distant and impersonal, characterised by a lack of sustained and direct dialogue. The absence of regular and personal interactions makes meaningful and continuous engagement difficult. That being said, some institutions, such as the Court of Justice of the European Union, are vital allies in upholding fundamental rights through high-impact judgments”.

As for the obstacles that prevent overcoming the hostility towards LGBT+ communities, the Spanish association argues that the hatred running rampant on social media is perhaps the primary problem. “The normalisation of hate speech, especially on social networks and in the media, is one of the main obstacles. That is why the [Spanish] Federation along with the most important social organisations in our country have been working for years to promote a State Pact against hate speech that targets the most vulnerable groups”.

On one crucial issue, however, everyone agrees: to overcome hostility towards LGBT+ communities, the focus has to be on education – everywhere, in schools, in the family, in community centres. As Gernot Wartner, general director of HOSI Linz Austria, emphasises, visibility is also crucial: “The media are called upon to ensure that their focus on us does not stop with Pride month”. Finally, there’s the role of political leadership. In the words of Wojciech Karpieszuk, columnist for the Polish Gazeta Wyborcza , “when politicians speak openly in support of minority rights and take a firm stand against discrimination, they send an important message to society. Leadership matters, especially in countries where hostility towards certain groups is still pronounced”.

(Ana Somavilla – El Confidencial, Wojciech Karpieszuk – Gazeta Wyborcza, Christian Schneider – Der Standard, Dimitris Angelidis – EfSyn contributed to the production of this story)

This article was published in the framework of PULSE, a European initiative coordinated by OBCT that supports cross-border journalistic collaborations.