A personal partition installed at a Starbucks store” (Image from Professor Seo Kyung-duk’s social media)

SEOUL, July 1 (Korea Bizwire) — A growing wave of discontent is brewing in South Korea’s café culture over so-called “café villains” — patrons who turn coffee shops into de facto personal offices, setting up laptops, monitors, and even partition screens for extended stays.

The controversy reignited after a viral photo showed a customer occupying a table with extensive equipment and leaving the spot unattended for a prolonged period. The incident has revived public debate about “카공족” (kagongjok, or café study/work people), whose growing presence in cafés has drawn frustration from business owners, particularly amid a sluggish economy.

According to industry data, the rise of the “kagongjok” phenomenon can be traced to the rapid increase in coffee shops beginning around 2015. However, while some businesses initially embraced the trend — marketing food items to long-stay customers — complaints have surged in recent years, especially as some patrons began charging electric scooters or monopolizing tables for hours with minimal purchases.

Studies show that in order to meet basic profit margins, coffee shop customers should stay no longer than about 90 minutes. When that threshold is exceeded, turnover drops and business suffers. Recent economic pressures, including slowing growth and reduced consumer spending, have made such losses harder to absorb.

Legally, however, options for curbing long-stay customers remain limited. Despite online claims citing a 2009 Supreme Court precedent, no ruling explicitly allows prosecution for long-term table occupation under obstruction of business laws.

Legal experts note that prosecution would require evidence of coercion or deception — standards not typically met by passive seating behavior.

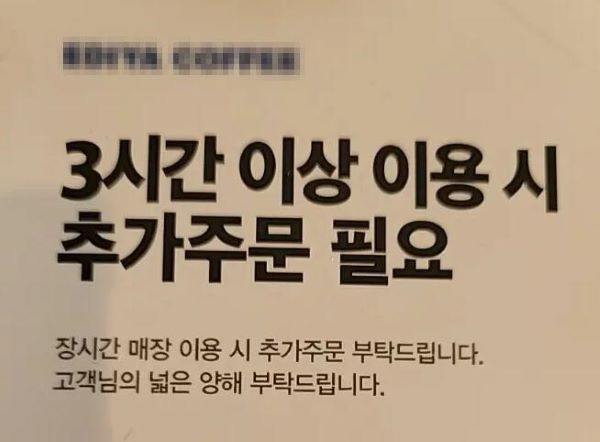

Instead, café owners must rely on private regulation. They are permitted to set house rules, such as time limits or minimum purchase requirements after a certain period, provided these policies are clearly posted and uniformly enforced. If customers ignore these terms and refuse to leave, owners may invoke trespassing or refusal-to-leave laws.

Indirect deterrents — such as limiting power outlets, restricting Wi-Fi access, using uncomfortable chairs, or playing loud music — are also within legal bounds, though some owners fear public backlash or online boycotts.

Still, such policies must respect legal boundaries around customer rights and anti-discrimination laws. A 2017 decision by the National Human Rights Commission deemed “no-kids zones” to be a form of unjustified discrimination, illustrating the potential risks of overly broad restrictions.

In the end, while café owners may regulate customer behavior through posted policies and environmental design, there is currently no legal basis for penalizing “kagongjok” solely for long stays — a reality that continues to test the boundaries of South Korea’s café culture.

Lina Jang (linajang@koreabizwire.com)