The following results are split into three overviews which become increasingly analytical with each step. Beginning with a descriptive overview of the data from interviews and SM, the following results will begin to look more closely at the received insights and identify possible analytical findings relevant to the scientific debate. Results will be presented chronologically (see Fig. 1), addressing each observed aggregate dimension (bold, italic) and describing the corresponding second-order themes (italic, title adapted to fit text flow in some cases). In suitable instances, quotes are used to exemplify the content of second-order themes. When possible, contemporary literature was incorporated to strengthen or interpret the observations.

This figure depicts second-order themes and aggregate dimensions. Outline color links themes to their aggregated dimensions, while color fill is used to represent a higher frequency in Japanese (orange) or German (blue) statements. Themes without color fill occurred evenly across national contexts. The hue reflects the frequency of occurrence (as a percentage; see legend under aggregate dimensions).

Perceptions of corporate impact: descriptive insights

In the data collected from activists, a narrative emerged regarding the corporate role in climate change. Predominantly, interviewees named corporations as the drivers of climate change, communicating that “it’s actually entirely the fault of companies that we find ourselves where we are.”ADE.23.H/H.1 This negative perception is also evident in current academic literature34,35,36,37 and on movements’ SM pages, where a significant number of datapoints depicts activity directed at corporations or projects. Nevertheless, activists also provided nuances to this perception describing corporations as capable of mitigating climate change effects. This content involves, e.g., activists highlighting that corporations are already equipped with ideas and solutions to the problems they are causing.

Activists also communicate drivers of corporate inertia, identifying problems around and within organizations that cause inaction. Internally, they explained that inhibitive organizational structures and limited employee power hinder transformation. Activists explained that, for example, corporations lack real motivation and commitment to change internal processes, but also that there is dissonance in corporations’ perception of themselves. Scholarship has likewise documented corporate inertia and its roots in organizational structures61. Additionally, employees within corporations are seen as limited in their capabilities, with activists explaining: “A conscientious employee cannot change the policies of an entire company. Conscientious employees will just not get promoted or will be fired.”AJP.22.S/H.5 This view contradicts established research on employee influence10,13,15 which has found that employees can and do positively influence sustainability transitions. Outside the company, activists see the current global economic system, with its focus on capitalism, as a hindrance (e.g., because growth and profit are then corporations’ main interests). Academia has also identified this as a stance reflected especially within transformative environmental movements62 that call for alternative, non-capitalist economic forms. Activists also see their limited impact on companies as movements as inhibiting transformation. For example, CMs seldom have leverage against corporations, and their efforts against companies sometimes go unnoticed. Current reports1 and the definition of fringe stakeholder17,18 align in this depiction of limited climate activist power. Activists also referred to the inhibitive relationship between corporations and the government, highlighting that, e.g., political activity is driven by mutual interest between corporations and political parties, limiting governmental power to adequately regulate corporations. The dissatisfaction with this relationship is also evidenced in movements’ online activity, where the government and its behavior in the context of corporations are questioned and criticized.

Activists’ views on drivers fostering corporate transformation mostly focused on their efforts as movements but also involved external drivers and circumstances. Activists explained that the scarcity of their protests can occasionally drive transformation: uncommon expressions of public opinion may cause individuals to become more aware of the issue or pay more attention. Additionally, insights were communicated about collaborating with other international movements to, e.g., heighten pressure by drawing international attention and thus elevating the impact. SM also provided insights into activists’ collaborations on efforts against corporations. In general, many movements are known to be globally represented22 and have been seen collaborating regularly at large events such as the conference of the parties (COP) or the World Economic Forum. Directly contesting companies (i.e., targeting a company and its branches rather than the government about the issue) and targeting the external image of companies (i.e., deliberately raising awareness of projects through protest in order to damage companies’ image, especially internationally) were depicted as transformative. SM insights also showed activists protesting outside company branches or on company project property. Outside the sample, such activity is made visible through climate litigation developments as well3,6,7,8,9. A view present in the interviews and collected SM data is further that corporations cannot be relied upon to regulate themselves, producing a desire for governmental action as a driver of corporate change. Lastly, it is suggested that financial damage and its impact on external risk perception could drive corporate change in the hopes that “… certain things are no longer profitable. So, it simply doesn’t make sense anymore to build new oil pipelines or LNG terminals.”ADE.24.S/H.8 This view has been documented by studies before, both pertaining to individual risk perception5 and also through recent insights on loss of firm value following climate litigation cases54.

The stated goals of protesting against corporations were consolidated in the dimension protest aims. As SM data shows, activists involve the government in their efforts by stating that their aim is affecting the political dimensions of the problem, i.e., focusing on revealing government–corporation power dynamics to the public and pressuring the government to change. Another intention stated by activists was affecting the implementation of projects by, e.g., physically impeding projects or sharing information to make projects seem like bad investments (also evident in the above quote on financial damageADE.24.S/H.8). The SM data likewise document activists’ physically blocking or protesting projects. Lastly, activists also aim at raising societal awareness about the general problem of corporate impact on climate change, explaining that they “just expose what [companies] are doing and … [want] to mobilize more people and … recruit more … young people into the activism.”AJP.26.H/H.1

Personal ideals related to vocations and paid work were collected as well to add further insights into their perception of corporations. Individuals explained the role of activism and environmental concerns in vocational choices. Several individuals communicated that, e.g., either their activism is how they came to the vocation they are practicing today or that their activism played a key role in their vocational choices. Individuals also communicated that activism is the main focus of their vocational future, such that they are looking to continue their activism later in some other form or that their future vocation is a mere means to an end, enabling them to continue their activism. Lastly, it was emphasized that current or future vocations must have a values- and environment-centered focus. One activist said: “I will NEVER participate in environmental destruction like this or in any humanitarian crimes. So, simply put, I will never do things that go against my values in any way.”ADE.26.S/H.5

Their role in the labor market was elicited through specific details pertaining to their employer choices later on. Individuals communicated their aversion to the current economic and corporate landscape, stating, e.g., their distaste for working for profit-oriented businesses or even corporations in general. They emphasized their unwillingness to work for corporations that are unsustainable or have been contested, with one activist asserting: “It is … inconceivable for me … to switch sides, … no reason in the world would now bring me to [provide specific vocational skill] for [company].”ADE.23.H/H.1 Nevertheless, some activists said they would consider contingent participation in unsustainable companies if, e.g., companies showed a serious and transparent commitment to reducing emissions or, as a complete contrast, to do corporate espionage. All these insights are in line with findings on the biographical consequences of activism32, especially environmental activism33, where such impact on vocational choices is well researched.

Underlining the importance of national context

Of the 22 second-order themes, eight differed in frequency between Japanese and German cohorts. An imbalanced frequency was identified when over 75% of the statements came from only one of the countries. The frequency of statements was broken down into two levels: slight (75–89%) and strong (90–100%). The imbalance in second-order themes is color-coded in Fig. 1. The following segments delve into the national specificities identified within the second-order themes.

Driving corporate transformation in Japan: various approaches and perceptions

The second-order themes making up the drivers of transformation yield observations specific to Japan. One example is the positive impact of protest scarcity as a driver of corporate change, which is a specifically Japanese phenomenon, tying in with what is known about protest sizes and frequencies in Japan51,52,53. In addition, Japanese activists emphasize the use of international collaboration more than German interviewees do, explaining that they “strategically … work together with activists from other countries … [to] put pressure onto those Japanese corporations.”AJP.26.H/H.1 Their presence on SM also shows how important it is to collaborate internationally. Japanese activists posted collaborations with other international movements, or at least mention of international partners or movements, more frequently than did their German counterparts. Prioritization of direct action against companies was similarly prominent not only in interview statements but in visual SM depictions of their efforts (e.g., photographic material showing their protests in or in front of companies). One reason why Japanese CMs in particular may actively choose to contest companies might be Japan’s “friendly authoritarianism [which] is based on soft social control by superior groups and organizations, providing a limited public sphere.” (p.2)51 In addition, the electoral and parliamentary system in Japan is associated with high costs for those contemplating a candidacy, making it difficult for average citizens to become politically active51. In line with their corporate focus and international networking, Japanese activists explained how damaging the external image of Japanese companies can be utilized to exert pressure because “[the companies] realize: okay … [there is] pressure, from abroad. And then the Japanese companies move. They wouldn’t move just from within the country alone.”AJP.22.S/H.5 Activists’ mention of these specific transformative pressure points gives the impression that the activists see the success of endeavors as linked with these cultural specificities. The focus is strongly set on the companies and how to affect them, with the current form of government potentially offering insights into reasons behind such strategies.

You could also say that I’m simply not interested in these companies

ADE.22.H/H.10

: German activists and their focus on the government

From interviews and SM data, it is evident that the German activists have set their sights predominantly on the government. They see the government as a problem, as mitigators, and as the target for their efforts. Activists’ SM pages frequently contain posts addressing specific politicians, political parties, and the general government, together with companies. When looking at their views on government as a driver, it becomes clear to some extent why their expectations are set on the government:

Also, as I said, … I … don’t expect companies, no matter how environmentally friendly they portray themselves outwardly, to really act according to other logics than profit logic, because that’s just how it’s dictated. So here, the responsibility lies with politics to create the framework conditions so that certain activities are no longer possible.ADE.33.H/H.9

Activists’ focus on the governmental side of this issue may be due to the contextual setting. During the 2021 election, the Green Party became part of the federal government coalition again. The party has shown signs of aligning itself with the concerns of such youth CMs by participating in and supporting their efforts63, yet it has also been the recipient of criticism by prominent activists like Luisa Neubauer64. Additionally, for the first time, the current ministry for climate protection is actually simultaneously the ministry of economy65, with its minister, Robert Habeck, being a member of the Green Party. Empirical explorations have also linked the activity of Fridays for Future in Germany to the success of the Green Party in the 2021 election31. These intertwined circumstances in politics and German CMs may have implications for activist perspectives, although any direct causal relationship remains to be confirmed.

Crossroads of corporate climate action: analytical insights

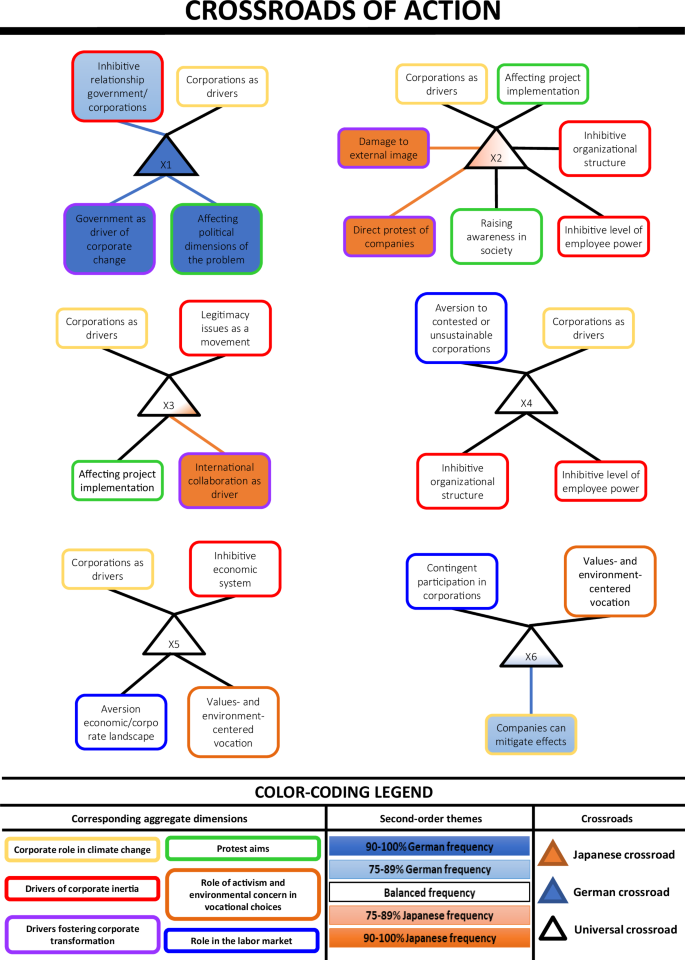

Finally, the data is analytically scrutinized to interpret where activist observations on corporate climate impact show signs of leading to action. The second-order themes will be used to represent activist perspectives, while places of action will be represented as crossroads (X1–X6, visualized in Fig. 2) between these perspectives. In light of the above reflection on national specificities, these were also considered when examining the potential crossroads in the data. Two crossroads had nation-specific implications, and four were observed in both countries. The result is a visual representation of the reciprocal interactions between corporate activity and CMs/activists. The analytical assessment focused not on connections between aggregate dimensions themselves, but on identifying interplay between the second-order themes of the aggregate dimensions. This was influenced by the comprehensive analysis of the descriptive data, with particular emphasis on the observed national-specificities within the second-order themes.

This figure depicts the analytical findings in the form of a crossroads of action, as described in the text. The crossroads are made up of second-order themes from aggregate dimensions. To identify the dimension of the themes, the outline of each theme has been color-coded to match a specific aggregate dimension (see legend and Fig. 1). Color-coding is also used to represent a higher frequency in Japanese (orange) or German (blue) statements. Themes without color fill occurred equally across national contexts. The hue reflects the frequency (expressed as percentage; see legend under Color-coding legend). The hue of the crossroads triangle is affected by the number of nation-specific second-order themes it encompasses.

These crossroads are analytical insights determined solely by the data available. It is an analytical sensemaking of the descriptive results and provides indications of where activity towards corporations emerges. Though this study upholds empirical interview saturation levels57, this is a representation of the actions mirrored by the present data and leaves open the possibility of other actions not listed here. Furthermore, for the sake of neutral observation of actions taken, the actions are not meant to be categorized in types or ranked in their success.

Governmental inaction on corporate climate impact: a German activist pathway to action (X1)

During the interviews, activists communicated that companies have negatively contributed to global warming. When discussing the potential barriers that favor inertia within companies, German activists emphasized the inhibitive relationships between the state and companies. In the subsequent analysis of possible drivers of transformation, government as a driver of corporate change occurred with an even higher frequency in German statements. Regarding protest aims, German activists again emphasized putting pressure on the government. All observations are similarly well documented through SM. German activists described their perception of the barriers to, but also of potential drivers of, transformation in their context and concluded that government is influential in corporate climate impact; thus, the protest aim is oriented towards the “governmental side” of the problem. This creates an observable crossroads where activists translate their observations into action.

Fostering Japanese corporate transformation: action driven through national specificities (X2)

During the interviews, activists expressed that companies have negatively contributed to global warming. When discussing the potential barriers that favor inertia within companies, activists communicated interorganizational issues like corporate structures and low employee power. Meanwhile, Japanese activists communicated nationally specific drivers of transformation that they utilize to counteract this inertia: contesting corporations directly and damaging corporations’ external image. This strategy is visible within their SM presence, with posts showing activists encroaching on company property and sharing information with civilians about corporate projects. This activity coincides with their aim, which is to raise awareness in society and affect the implementation of corporate projects evaluated as unsustainable. These Japanese activists described their perception of the barriers, identified nationally relevant drivers of transformation, and drew conclusions for themselves and their activity. By using their knowledge of Japanese business practices and society, they actively employ protest methods focused on corporations to amplify their impact. This raises awareness within Japanese society and may also affect the success of corporate projects.

Climate action across borders and movements: turning weaknesses into strengths (X3)

In the face of companies’ undeniable contributions to climate change, activists recognized their limited impact on corporations as a potential barrier to corporate climate action. Yet, activists identified a driver of transformation that they can utilize to potentially counteract this issue: international collaboration. Though more frequently mentioned by Japanese activists in interviews, insights from SM data show collaborative work and sharing of international activist efforts on the German CM pages, as well. In addition, when analyzing the German data more closely, the topic of collaboration becomes increasingly evident, but on a national scale, with multiple local groups collaborating to amplify the impact of protests. The aim is to affect the implementation of projects by calling national and international attention to the projects and causing pressure. These activists described perceiving their legitimacy issues as a barrier. They acknowledged their limited impact on companies and counteract this weakness by involving other movements and countries in the effort to change or stop unsustainable projects.

There is absolutely NOTHING to be gained from working there

ADE.23.H/H.1

: The path leading away from corporations (X4)

In interviews, activists expressed favoring values- and environment-centered vocations. Companies, by contrast, were seen as contributors to global warming whose general structure and lack of individual employee power made corporate climate action unlikely. Thus, when questioned about their own role in the labor market, they showed an aversion to the idea of working for the unsustainable companies they contest. In this case, the activists described their perception of the barriers within these organizations and took action as individuals: They have specific personal values and environmental beliefs that need to be met by their vocations. Problematic organizational structures are interpreted as hindering the fulfillment of such expectations and, thus, lead to disinterest in being a corporate employee.

A bigger problem and a bigger picture: inhibitive economic systems and activists’ vocational choices (X5)

In interviews, activists described the current economic system as inhibiting corporate change, leading companies to continue to contribute negatively to global warming. Activists also emphasized their preference for values- and environment-centered vocations. Regarding their own role in the labor market, they expressed an aversion to working for corporations which are profit-oriented. Activists described their perception of the barriers around these organizations and drew conclusions for their personal lives: corporations’ sustainability transformations are seen as impeded by the capitalist system. As environmentalism is central to activists’ vocational decisions, their observations may lead their search for vocations away from companies following a profit logic.

A positive outlook: a pathway to collaborative action (X6)

During the interviews, the activists pointed out that companies can actually mitigate the severity of climate change effects through their activities. Activists also communicated that they favored values- and environment-centered vocations. Thus, when questioned about their own role in the labor market, they expressed openness to participation in corporations if the efforts of that particular corporation were rooted in true visions of transformation (i.e., not greenwashing). As activists see the potential in companies, those companies who are aiming to truly change their practices could be considered as possible future employers.