Democracy is based upon the belief that there are extraordinary possibilities in ordinary people. These words were once spoken by Harry Emerson Fosdick, America’s greatest liberal preacher of the 20th century.

He lent a strong voice of reasoned faith and enlightened hope to a bewildered country at a time when it badly needed it. He grounded his faith in his personal experiences, in the tragedies of those he met during his lifetime, and in their hopes and dreams.

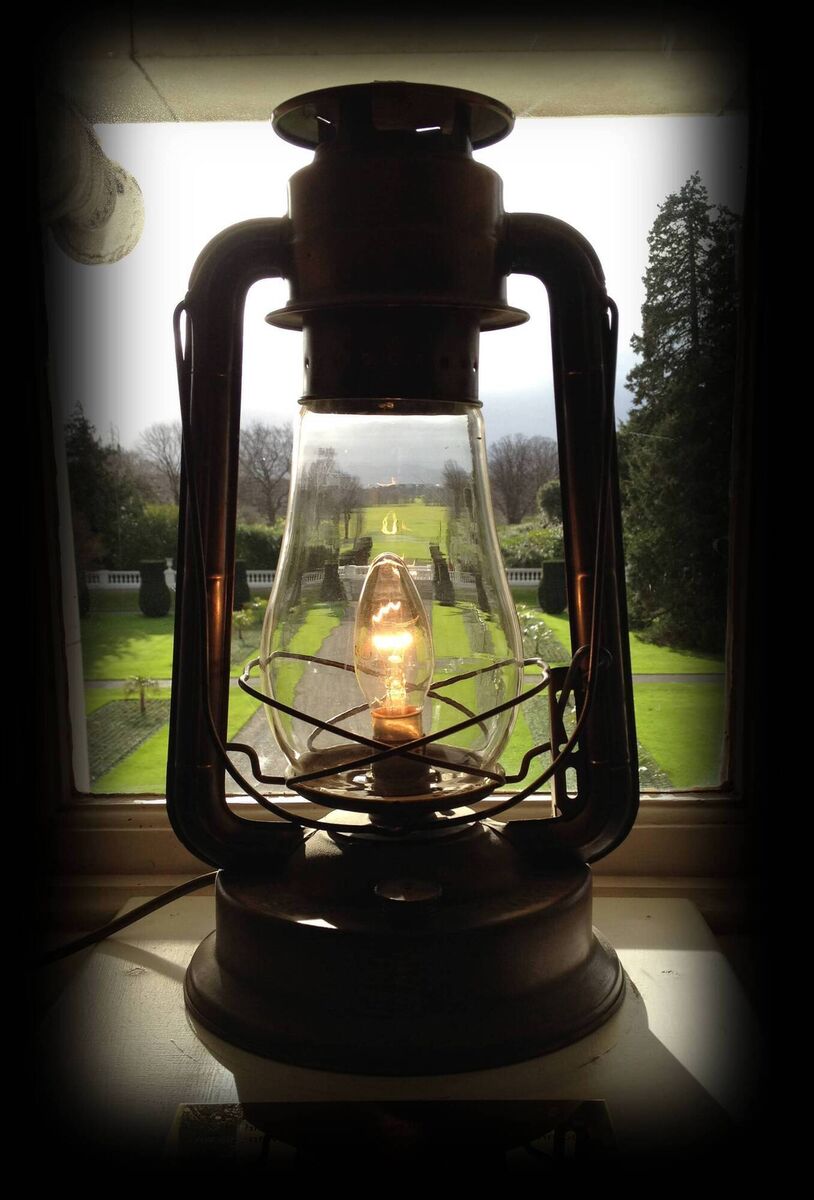

Ordinary people can be dauntless when the vision that drives them becomes their calling. In 1990, days after becoming president, Mary Robinson placed a Tilley lamp in a window in Áras an Uachtaráin. The lamp’s constant glow was a symbolic beacon to our emigrants, and to their millions of descendants.

No matter where you were in the world, the light from the lamp became a promise from the occupier of the highest office in the land that a warm welcome would always be waiting, that this would always be home. The lamp still shines today, visible from the main road of the Phoenix Park.

Some 35 years later, such a gesture might seem trivial, even corny.

Mary Robinson’s diaspora pledge demonstrated how an office that had previously been regarded as unimportant — a “makey-uppy job”, as Ryanair’s Michael O’Leary described it — suddenly became an expression of solidarity and a role that has since carried enormous respect.

Loved ones through the generations who had been forced to leave home to find a more sustainable life elsewhere were, for the first time ever, being told they would always be foremost in our thoughts. Robinson didn’t just become her role; the role became her. That’s what makes an extraordinary president.

An impending election is on yhe horizon, as they say. It’s a hot topic of conversation. There’s only one problem — it appears that so far no one wants the job. Am I surprised? Not really.

It’s not a straightforward job. Consider it more akin to a seven year-long vocation during which time the incumbent surrenders their old way of life for a term that only they can define, within the rigours of what they are permitted to do, which outwardly appears to be very limited. But that’s not true.

In a 1990 interview with Hot Press, prior to her election, while discussing whether the president of Ireland was merely just a ceremonial figurehead or not, Mary Robinson said: “The only restrictions on the office of presidency are when the president is carrying out official powers and functions.

“However — and it’ s a big however — there is no constitutional restraint on what I do outside of those official functions.”

Charles Haughey almost had a meltdown.

All he could see was Pandora’s box.

President Mary Robinson with a clearly unhappy Charles Haughey and a disappointed Brian Lenihan in the backgournd.

President Mary Robinson with a clearly unhappy Charles Haughey and a disappointed Brian Lenihan in the backgournd.

Robinson brought volumes of experience as a constitutional lawyer to the office she was elected to shortly after that interview. Could she have achieved as much as she did without her background in law? It’s unlikely.

Without a legal-eyed knowledge of the constitution, it would have been almost impossible to find ways to be creative and as definitively empathic as she was; and, in her own words, to use it “to raise questions that don’t come through in the present, rather narrowly-based system, to lend a voice to those on the ground”.

She often spoke about how “lonely” her role was, considering the denunciation her presidency drew from church pulpits, and the level of hate mail she received.

Then there was the meeting with Haughey, who arrived with a “legal opinion” in his hand, which claimed she was doing more than the constitution allowed her role. He quickly realised he had picked on the wrong woman and backed off.

What was it precisely that made Mary Robinson extraordinary? In short, her unwavering faith in what she believed she had to do, because she knew she could. That became her legacy

She created a new style of presidency — a job she never wanted until her husband Nick convinced her to run. It was a blueprint, grasped in their own unique ways by her two successors, Mary McAleese and Michael D. What did they all have in common? An ability to understand that in order to be relevant they had to fearlessly challenge the injustices that governments chose to ignore.

Harry Fosdick declared that “the ultimate criterion of any civilisation’s success or failure is to be found in what happens to the underdog.” It’s been at the heart of the role of three extraordinary presidents, and it’s imperative it doesn’t change for whoever is elected in November.

But is there anyone out there who is capable of maintaining that Tilley lamp in the window, and all it stands for, in the way it has been for 35 years?

And why are we obsessed with the daft notion that a celebrity would make a great president?

Joe Duffy is the latest in a parade of showbiz lineage to be mooted as a possible candidate. Within hours of his Liveline retirement, the Leinster House leaks department spouted that there could even be a multi-party consensus on putting him forward.

But would he really want the gruelling television bun fights while at the mercy of his former colleagues ahead of the election?

The light that shines from an upstairs window at Áras an Uachtaráin. The light is a symbolic beacon, lighting the way for Irish emigrants and their descendants, welcoming them home.

The light that shines from an upstairs window at Áras an Uachtaráin. The light is a symbolic beacon, lighting the way for Irish emigrants and their descendants, welcoming them home.

Duffy will forever live on in the shadow of his ‘Talk to Joe’ persona — a privileged role he held for 27 years; a role he’ll continue to be associated with if he runs for election.

It’s a huge gamble for any celebrity. You bring a life of fame to the role of the country’s most eminent citizen. That’s not necessarily a good thing.

Would it be possible to reinvent yourself, considering you’ve spent most of your life as a household name? How can you ever be anybody other than the star you’ve always been?

Gay Byrne recognised it, and following serious consideration steered clear of an invitation by Micheál Martin. In 2011, he told me that success meant living his entire life “in a goldfish bowl”. If he were to be elected, he would simply be swapping one fish bowl for another.

Then there’s the possibility that you’re beaten in the polls — your past eclipsed by being remembered as the candidate who failed to get elected. The Irish invented begrudgery, while a star’s ego is as fragile as an egg shell. Never the twain shall meet.

In recent years, there’s been a tendency to look to Montrose in the hope of finding the next president.

Thankfully it’s never happened. Political parties love to adopt a celebrity — and no finer place for their media squeeze than a stint in the Áras. If anything, it’s an insult to the office

Gay Byrne summed it up when he said, “I didn’t have the stomach for all that”.

Marian Finucane also ran for cover in 2016, although acknowledged that it was nice to be asked.

So will it be ‘Vote for Joe’ next November? Is it likely that names such as Marty Morrissey, or Joe Brolly, or Michael Flatley will be on the ballot paper? They’re all legends, but are they the stuff of future presidents? Not if a rich 35-year legacy is anything to go by.

Our next president is out there — one who will want to emulate three predecessors; one who can be likened to a Tilley lamp for all seasons; one who can, as Harry Emerson Fosdick did, lead us into a future that demands insight and daring. If you think you would make a great president, then the job’s probably not for you.