The Invisible Fracture Lines of Israel

In Israel, Jews are united by homeland but divided into very different groups

Posted by hrpanjwani

The Invisible Fracture Lines of Israel

In Israel, Jews are united by homeland but divided into very different groups

Posted by hrpanjwani

1 comment

Beneath Israel’s often-discussed external conflicts lie profound, invisible fracture lines. The nation, a complex mosaic of ethnic and religious groups, faces an internal political struggle as intricate as any of its regional challenges. The country’spolitical system, based on pure proportional representation, often sees a bewildering array of parties (currently over a dozen hold seats in the Knesset), leading to coalition governments that form, split, and recombine with a dizzying frequency, a phenomenon almost unique on the global stage.

As much as many, myself included, might view Netanyahu as a figure marked by corruption and a hunger for power—a stark contrast to the unifying legacy of Yitzhak Rabin—it’s undeniable that he has an unparalleled ability to consistently coalesce the disparate factions into a functioning government. Many in his coalitions may loathe each other in private, but Netanyahu has a talent for getting them to sit at the same table. As much as I would like to see Netanyahu gone from Israeli politics, it is hard to see who else could unify the parliament behind themselves once he is gone and such a vacuum could cause things to really spiral.

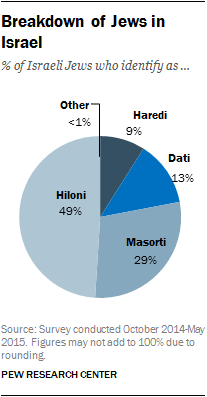

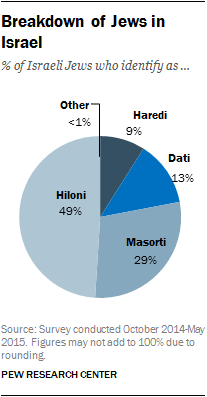

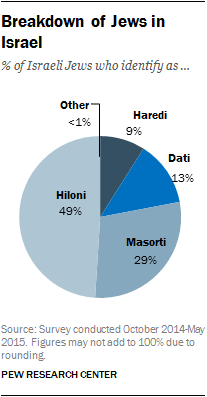

And that brings us to the heart of the matter. The demographic “bomb” that hasn’t gone off yet is the huge diversity within Israel and how that diversity often creates tension instead of unity. Israel projects an image of being mostly secular and westernised, but that hasn’t been the reality for a while. The country today includes a huge population of Ashkenazi, Sephardi, Mizrahi, Ethiopian, and various ultra-Orthodox communities with different cultures, customs, and worldviews.Not to mention a significant Arab population with its own issues and a smattering of Druze. That’s a lot of baggage to pack into one tiny nation, especially when the groups don’t always see eye-to-eye and have significant cultural clashes with each other.

Zionism has been the political project that has tried to smooth over these differences and create a shared Jewish identity, but in practice, it has often amounted to little more than just papering over deep divides. That sense of unity feels increasingly stretched.

Ben-Gurion saw the writing on the wall decades ago. He pushed hard to replace Israel’s proportional voting system with a constituency-based one because he believed the current system gave too much power to small, grievance-based minority parties. That reform never happened and now the Knesset is regularly gridlocked with a battlefield of special-interest groups that all require their own appeasements to get anything done.

Politically, parties like Likud have maintained their strength by securing significant support from large blocs of voters, particularly within Sephardic and Mizrahi communities, who historically felt marginalised by the earlier, predominantly Ashkenazi, left-leaning establishment. This, combined with the eye-wateringly fast-growing ultra-Orthodox population, who often favour bloc voting and prioritise religious interests, explains the diminished sway of the more secular, left-leaning Ashkenazi elite.

Ironically, what’s kept this fragmented system functioning for so long is the external pressure: the sense of being surrounded by enemies. The military and intelligence services soak up a huge portion of resources, as the one thing almost everyone agrees on is that the best defence is a good offence. Israel has one of the most sophisticated diplomacy and propaganda arms in the world that ensures consistent, abiding and deep support from the West, despite Israeli nuclear ambiguity, which is the closest thing we have to a universal anathema in the modern world.

But here’s the uncomfortable question: what happens when that external pressure starts to fade? That might happen by the end of this decade. Without a shared existential threat to unify against, can Israel hold itself together? Or will its internal factions start turning on each other in ways that make external enemies look like the least of its problems?

Comments are closed.