CYNTHIANA — Eight inches below ground, a buggy bomb ticks away.

Millions of periodical cicadas bide their time, feasting on tree roots and counting the years. They don’t wear watches or keep calendars, yet every 17 years — including this year — Brood XIV emerges across parts of the region like clockwork.

Chris Simon, professor emeritus of ecology and evolutionary biology at the University of Connecticut, has been studying cicadas for 51 years and is still trying to understand how these small enigmas do just that.

“They’ve got to have an internal clock,” she said. “They’ve got to be counting and keeping track of the years. Natural selection will work against them if they come out in the wrong year because they’ll be eaten and they won’t leave any offspring.”

With their signature red eyes and orange lace wings, Magicicada — a genus name that suggests inherent mystery and wonder — have one of the longest lifespans of any bug in North America.

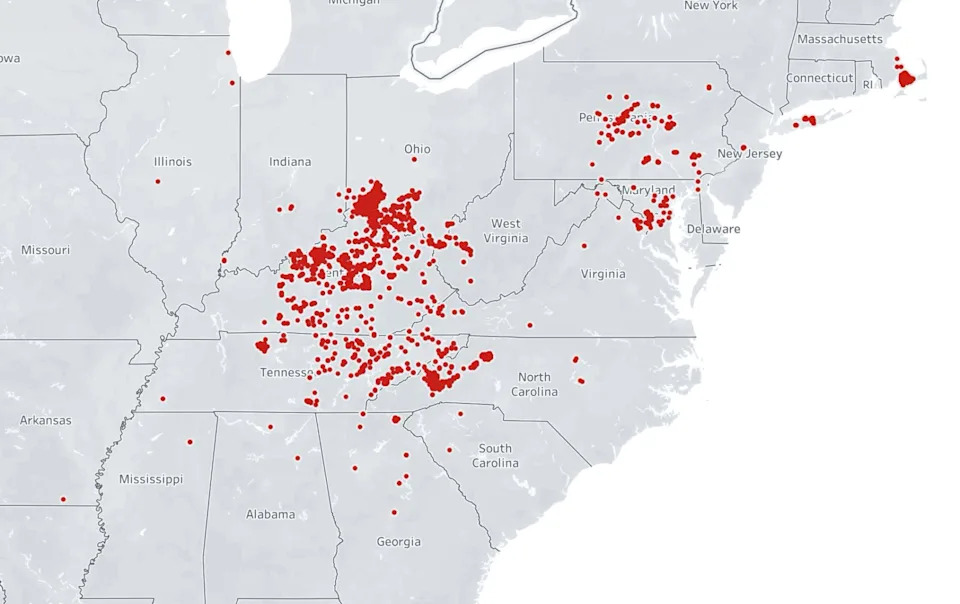

The “Bourbon Brood” is concentrated in Kentucky but reaches from Massachusetts to Georgia to Ohio.

Cicadas molt, leaving behind their exoskeletons on trees, bushes and benches at Veterans Park in Lexington, Kentucky. May 21, 2025.

During big emergence years like this one, entomologists follow the bugs across the region to study their curious timekeeping, their response to climate change, and the man-made consequences they suffer from deforestation and development.

But scientific questions are not all cicadas leave behind. The symphonic soundtrack they unleash is emblematic of summertime across the eastern U.S. Their music is buzzing with both nostalgia and the possibility for new traditions.

In the Bluegrass State, an artist forages for their shells, a small business owner keeps a collection of their corpses, and a parent cooks them up for her kids, revealing the myriad ways our lives intersect with the brood whose one-in-every-17-year appearance is ingrained in our collective imagination.

“There’s nothing and then all of the sudden there’s millions of bugs in the landscape in this macabre Mardi Gras of singing and mating and dying and being eaten,” said Jonathan Larson, an extension entomologist at the University of Kentucky. “Without them, we would lose some of the sounds of summer.”

‘Their eyes change from white to red’

When the soil temperature reaches 64 degrees, usually in late spring, cicadas dig up through the earth.

”They make the decision to emerge in the fall before they come out,” Simon said. “You can tell that they’re ready to emerge because their eyes change from white to red.”

With bellies full of tree sap, they burrow upward, leaving the ground pocked with tell-tale holes. From there, they travel up tree trunks to undergo their last transformation. Over the course of a few hours, they shed their nymphal skin, emerge as adults and get down to business.

They have just four weeks to complete their life’s mission: reproduction. Males use their three-song repertoire to group together, harmonize, and individually serenade female cicadas.

Jonathan Larson, an entomologist at the University of Kentucky, collects cicada shells in Lexington, Kentucky, with Texas artist Diego Miró-Rivera on May 21, 2025.

“ It’s sort of like a bunch of dudes on a college campus being like, ‘Bro, this is the best tree. You’ve gotta come to this tree,’” Larson said.

With strength in numbers, they sing together to entice females to the tree. Females respond by demurely clicking their wings to signal they’re interested. When the deed is done, the male dies almost immediately. The female lives only a bit longer to lay her eggs. Six or seven weeks later, the orphaned nymphs are born.

This is the drama behind their weekslong concert.

Their raucous party is how most have come to know them, but while underground, cicadas spend the majority of their time feeding and counting the years through the ebb and flow of sap with the seasons.

” They can’t count in the way that we count. There is sort of a logging of ‘the sap came, the sap went,’” Larson said. But what researchers don’t know for sure is how they remember the passage of time.

“We think that they count in four-year windows,” Simon said.

Their decision of when to emerge could be due to a gene expression, or the “turning on” of a gene, signaled by biochemical processes in their bodies.

Simon and others are looking for answers by studying cicadas’ genetic instructions. They’ve published the complete genome, or set of genetic instructions within DNA, of one species of Magicicada, and are working on several others to finally find the answer.

But Simon said funding was already hard to find even before the Trump administration came into office and started slashing science budgets.

“The frustrating thing has been trying to get funding from the National Science Foundation to carry out the research because it is so unique and doesn’t fit squarely into any specific panel,” Simon said. “Now that the government is attacking science funding, it will be even more difficult.”

Natural art, 17 years in the making

All over the state, ghostly shells that once belonged to Brood XIV litter tree trunks, park benches, gravestones and porches, left to degrade. But one bug’s trash is another man’s treasure.

Diego Miró-Rivera, a Texas artist, has spent the past two summers crisscrossing the country collecting shells in 32-ounce, plastic deli containers. He turns them into what he calls “cicada paintings” ― kaleidoscopic arrangements of cicada exoskeletons hooked on burlap canvases.

“I like to tell people the art is 17 years in the making,” he said.

Diego Miró-Rivera collects cicada shells at Veterans Park in Lexington, Kentucky, on May 21, 2025. Rivera scraped the shells into a 32-ounce deli container from high up on a tree branch.

Last year, Miró-Rivera collected 100,000 shells. This year, he’s driven through Louisville, Frankfort, and Lexington, collecting 30,000 carcasses, so far. During a stop in Lexington, he joined up with Larson, the UK professor, to gather shells together.

“It’s a great shame to segregate science and art,” Larson said.

From a nearby tree, Miró-Rivera unhooked a cicada husk and spun the fragile, transparent shape in his hands. His art puts an emphasis on natural mediums like hay, snow and seeds. Across Kentucky, he said, cicadas were gifting the landscape with self-portraits.

“I try to celebrate the cicada as a sort of accidental sculptor,” he said.

Climate change effect on cicadas

In 1969, part of Brood XIII emerged in Chicago four years ahead of schedule. They left holes tunneled in the dirt, wings scattered on the pavement and guts smeared on car windshields, but they didn’t emerge in big enough numbers to become self-sustaining. They were easily picked off by predators.

But in 2020, Simon said, enough of Brood XIII emerged ahead of their 2024 arrival time that they were able to sing, mate, and reproduce. They appeared to be starting a new population, which could eventually split into its own brood.

Whether or not early emergences are happening because of climate change is part of what researchers are studying. With warmer temperatures, Simon said, more cicadas will get to their last growth stage faster and be ready to emerge earlier.

“One of the most important things that they can teach us is what we have changed about the environment around us,” Larson said.

Data from Cicada Safari, a crowdsourcing app developed by Gene Kritsky, an entomologist and historian at Mount St. Joseph University in Ohio, showed 38,000 cicada sightings by June 16, 2025.

Citizen science efforts are increasingly important to how scientists track them. Cicada Safari is an app developed by Gene Kritsky, an entomologist and historian at Mount St. Joseph University in Ohio, that allows people to log and submit the locations of periodical cicadas.

In the 1840s, entomologist Gideon B. Smith published notices in newspapers asking readers to send him their observations. Now, Kritsky does something similar, using the app to help map their emergences.

“The most important thing is to get the word out to people to let us know if their populations were self-sustaining,” Simon said. Did they last the full four weeks? Were they singing? These are some of the questions she is interested in during big brood emergence years like this one.

Cicadas are friends (and food)

Once they’ve died, cicadas’ burnt-out bug bodies fall to the base of their chosen tree and, over the course of a hot summer, decompose with a stink like rotting flesh. Here begins a new saga — their corpses provide rich nutrients for the surrounding plants and animals.

Big emergence years like this one cause nutrient pulses that help sustain regional ecosystems. Cicadas’ burrow holes allow water to irrigate the soil, bringing nutrients down to plant roots and preventing run-off, Kritsky said. They are important to eastern deciduous forests and, it turns out, to all kinds of bird species.

“Just imagine walking outside your door and seeing the world swarming with flying Hershey’s Kisses,” Kritsky said.

Card-carrying herbivores, seed-eaters, and omnivores switched to a cicada-heavy diet during a brood emergence in Washington, D.C., in 2021, according to Martha Weiss, a professor of biology at George Washington University. In the year after a big emergence, nestling and fledging weights of birds typically increase. But because the emergences are infrequent, they can’t be relied on as a consistent meal.

Much like an all-you-can-eat buffet, predators eventually get tired of them as a singular food source – a strength in numbers strategy that cicadas use to stay alive.

Cats, dogs, turkeys, and even humans eat them, too.

Shawn Sorrell’s makeshift recipe for cicadas stars truffle oil, sauteed sage and a cast iron skillet.

Silas Sorrell, 12, cooks cicadas in a cast iron skillet at his home in Harrison County, Kentucky, on June 1, 2025.

Her farm in Harrison County was buzzing with them this summer. Down by the riverbank, they fluttered from waist-high grass to stinging nettle leaves. Sorrell collected five in an old jar and drove back home where she called her kids into the kitchen for a snack.

Sorrell’s son, Silas, 12, took charge, cooking them in the pan and flipping them intermittently for an even sear. Their wings turned crisp and flaky. They caved in on themselves, sizzling on the stove, ready to be smeared like butter across toast or eaten whole.

Silas arranged them on a plate in a circle with sage leaves. Shawn sprinkled them with salt. After a prayer, they each took a bug and ate it without making a face.

“They taste kind of like mushrooms and chicken,” Silas said, as he finished off the plate.

Last year on the road, Miró-Rivera ate them à la mode with vanilla ice cream and drank cicada distilled malort – shooters floating with exoskeletons.

And Larson has eaten them in a multicourse meal prepared by a chef. They were sprinkled into tuna and wild rice, and for dessert, with mulberries and funnel cake.

“ They’re very versatile,” he said.

‘Canary in the coal mine’

Because of their reliance on trees, cicadas are also indicators of broader ecological health.

“You can kind of think of them as a canary in a coal mine,” Larson said.

In any given area, if they can live for 17 years underground, then the environments they depend on are healthy enough to support them. If they can’t, that habitat might be undergoing degradation.

That degradation could come as a result of deforestation and urbanization. Over the past century, people have been cutting down trees to make room for agriculture and development, but cicadas count on those trees for food and mating grounds. In places where trees have been removed, cicada populations have dwindled, leading to a patchier distribution and sometimes extinction, Kritsky said.

In 1954, Brood XI, in Connecticut, Massachusetts and Rhode Island, emerged for the last time.

”New England was 80 to 90% cleared during the 1800s,” Simon said. “That’s why there’s very few cicadas left in New England except along rivers and where there are still trees.”

But through protection and maintenance of their ecosystems, dwindling numbers can be brought back.

Simon said it comes down to how we build our communities. In the suburbs of Washington, D.C., and Baltimore, there are very healthy cicada populations, she said. As those cities expanded outward, land that had once been cleared for agriculture was re-planted with trees for residential neighborhoods, and cicadas moved back in.

‘Guardians of time’

In Larson’s department, they call cicadas “guardians of time” for the way people are able to track their histories through their cycles.

“ I think the most wonderful thing about them is the song, and the fact that it’s clearly echoed throughout human imagination,” Larson said. “For millennia, we have ancient Greek sources that tell us they were writing myths about how the cicada came to be, how the cicada can play a role in our singing and our music playing.”

Brood XIV, whose party is now at its end around Kentucky, goes back centuries, at least. Indigenous communities likely lived alongside it for decades, Larson said. And it emerged in 1634, just in time to baffle the pilgrims when they landed in Plymouth.

“There was such a quantity of a great sort of flies like for bigness to wasps or bumblebees, which came out of holes in the ground and replenished all the wood … and soon made such a constant yelling noise…as ready to deaf the hearers,” William Bradford, the governor of Plymouth Colony, wrote that year.

Since then, they’ve only emerged 23 times.

At her house in Harrison County, Theresa Brandenburg keeps a small wooden curio box. Inside lie a couple of beetles, a bird skull, a “dog day” annual cicada, and a three-legged periodical cicada.

She started her collection in 2021 after a fellow insect lover and friend, Renna “Merry” Lake, died. Lake had a few bug bodies of her own, including the jewel green cicada that’s Brandenburg’s favorite. After Lake’s death, she took over the collection, adding the strange treasures she finds.

This year, while her out-of-town family was visiting, she did her best to share her interest with a younger generation.

“My granddaughter is afraid, but I finally got her to hold one,” she said. “I remember being like that when I was really little. Maybe one day she’ll be talking about how much she loves them, too.”

Brandenburg remembers seeing them for the first time while standing on her porch in Augusta, Kentucky, as a kid. She listened to their steady hum over the sound of her dad playing a Cincinnati Reds game on the radio.

“I heard cicadas out there and the wind. The front door was standing wide. Isn’t that funny,” she said. “That those bugs can make a whole memory come out?”

This article is part of a collaboration between The Courier Journal and Boyd’s Station, a Kentucky non-profit that provides emerging artists and student journalists a rural place to hone their craft. Sarah Henry received the 2025 Mary Withers Rural Writing Fellowship grant at Boyd’s Station.

This article originally appeared on Louisville Courier Journal: Cicadas of Brood XIV finish Kentucky emergence cycle