It’s an infringement of human dignity. Just because I’m older, I can’t work where I’ve worked my entire life.

—Gwon Oh Hoon, 52, attorney, Seoul, August 27, 2024

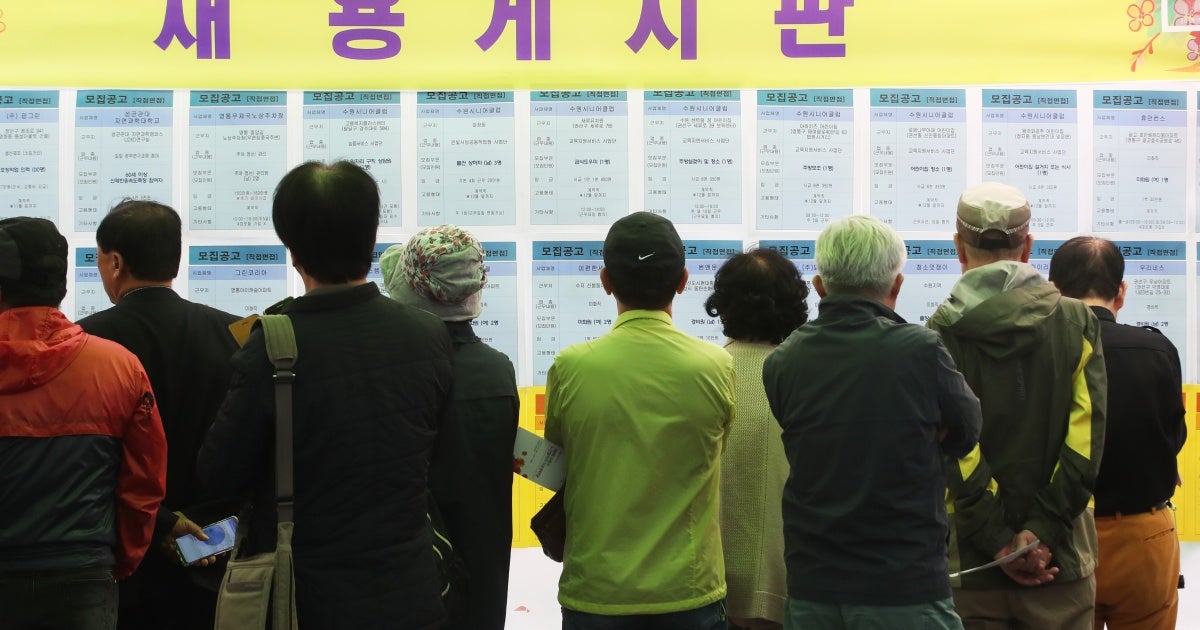

Age-based employment laws and policies, a hostile workplace culture, and a weak social security system harm workers in the Republic of Korea (South Korea) as they get older. Mandatory retirement ages force some older workers to retire. Regressive wage policies reduce their salaries. And re-employment programs push them into lower-paid, more precarious work. Inadequate social security compounds this, creating a system that punishes workers for getting older.

This report, based on interviews with 34 people ages 42 to 72 working in South Korea’s public and private sectors, examines the harm three age-based employment laws and policies do to older workers—the mandatory retirement age of 60 or older, the “peak wage” system, and re-employment policies—and how insufficient social security programs exacerbate this. It focuses on how current domestic laws and policies discriminate against older workers, rather than individual employers’ actions.

Human Rights Watch finds that workers from age 40 and up face hostile work environments, ageism, and discrimination based on their older age.

Older workers told Human Rights Watch they were humiliated when younger colleagues or clients used age-based language in a derogatory way towards them. They felt humiliated when clients called them ajumma (아줌마, married or middle-aged woman), and younger colleagues used noin (노인, older person) to refer to them in a derogatory way, as unable to do anything or keep up with the way younger people think. Language that perpetuates negative stereotypes and prejudices about older age and older people is verbal abuse and a form of ageism, and creates hostile working environments for older workers.

Employers often feel older workers are a burden on their companies. In a 2021 survey, Korea Enterprises Federation, a membership organization representing South Korean businesses, found that 58 percent of companies surveyed felt that employing people beyond the age of 60 would be a burden because of their “declining productivity,” additional salary-related costs, and an unspecified negative impact on hiring younger workers.

The South Korean law prohibiting age discrimination in employment, the Act on Prohibition of Age Discrimination in Employment and Elderly Employment Promotion, allows employers to adopt a mandatory retirement age of 60 or older, meaning both public and private sector employers can force workers to retire based only on their age, not job skills. Y. Kyung Hee, 59, has worked for 27 years in a public research institute where she is now a professor. She faces mandatory retirement in one year’s time. Work for her is not only a way to earn money but also something meaningful she does every day. “I’m worried about the mandatory retirement age as I can’t imagine not going to work every day,” she said. “I feel afraid.”

The fear, anxiety, loss of belonging, purpose, and dignity, and financial worries that older workers forced to retire under the mandatory retirement age described to Human Rights Watch indicate significant emotional and psychological distress and harm to their mental health and well-being, which studies have confirmed.

D. Young Sook, 59, after working as a nurse for 36 years, is anxious about loneliness and isolation after she is forced to retire at 60. “I can’t imagine myself being out of this organization,” she said. “It would feel like standing by myself on a windy road.”

Human Rights Watch found that the “peak wage” system, in which employers can reduce older workers’ wages during the three to five years before their mandatory retirement, also causes mental as well as financial harm to older workers.

G. Young Soo, 59, is facing mandatory retirement in one year. He joined an insurance company at 23 as an office worker and has worked as a branch director and team leader for both sales and training. His employers first reduced his salary by 20 percent when he was 56. They further reduced it by 10 percent each year so that at age 60, he will earn just half, 52 percent, of what he earned at 55. Although the hours and intensity of G. Young Soo’s workload stayed the same under the peak wage system, his decision-making authority was reduced in addition to his salary. After 36 years of loyal service, he felt the company had mistreated him.

Other older workers told Human Rights Watch about their demotivation, sense of deprivation, and anger at how they have been treated under the peak wage system. And it is not only their salary that is affected. The peak wage system can have a negative knock-on effect on other financial entitlements. G. Young Soo and his employer pay a total of 9 percent of his salary into the National Pension System. Since his salary has been reduced, so too will these payments and the eventual amount he receives when he collects his pension. “It is discrimination because our income has been reduced because of our age,” G. Young Soo said. “It is not justified.”

Under international human rights law, discrimination means any distinction, exclusion, restriction or preference or other differential treatment that is directly or indirectly based on prohibited grounds of discrimination and which has the intention or effect of nullifying or impairing the recognition on an equal footing of all rights or freedoms. Differential treatment on a prohibited ground, such as age, should be subject to a justification test to ensure it has a legitimate aim and is both proportionate and necessary.

However, under the Act on Prohibition of Age Discrimination in Employment and Elderly Employment Promotion, mandatory retirement ages are exempt from such justification tests. They are never considered discrimination, and older workers are unable to challenge them and seek justice if they believe their rights have been denied.

Human Rights Watch research found that these age-based policies constitute discrimination because they are neither proportionate nor necessary. The harms caused by the mandatory retirement age and peak wage system outweigh any benefits. Neither appears to have achieved their respective aims of keeping older workers in their main jobs until at least age 60 and financing the employment of younger workers. And they are not necessary because there are less harmful alternative policies that the government could use to achieve these aims.

Furthermore, the peak wage system is based on an ageist stereotype that older workers are less productive than younger ones; treating people differently based on stereotypes has also been found to be discrimination.

Although these age-based policies force older workers to retire and forcibly reduce their wages, local and state governments have a legal obligation under the Act on Prohibition of Age Discrimination in Employment and Elderly Employment Promotion to support older workers’ re-employment after retirement from their main jobs. Human Rights Watch found that these re-employment programs, too, cause harm to older workers, forcing them into lower-paid, more precarious work.

Employers can re-employ older workers under less favorable working conditions than before their retirement. At the public research institute where Y. Kyung Hee, 59, is a professor, employees can be re-employed to work for one more year after mandatory retirement at 60.

“You can teach twice a week and get KRW2.5 million [Korean Republic Wons, or US$1,873] per month,” she said. Her salary before it was reduced under the peak wage system was KRW6.5 million ($4,869) per month.

Data from South Korea’s Ministry of Employment and Labor show that, on average, older workers earn 29 percent less than workers 59 and younger, and Statistics Korea, the government statistics bureau, reports that they are nearly twice as likely to be working in less secure “non-regular” work than younger workers.

The jobs older people can get may be jobs that others do not want. C. Sung Ho currently assesses people’s eligibility for social security entitlements. He said he has heard from workers older than him that he could get a job as a janitor managing a building after he is forced to retire. Older men can find such work, while older women often find that their only employment option is as a care worker. Kim Ju Ran, 59, has been a care worker for four years. She explained why young people avoid becoming care workers:

A lot [of care workers] are in their late 60s and 70s, but there are no young people entering our industry because, compared to the workload, the income is so low. You have to bathe, cook, and change their diapers when they urinate and defecate. Young people are overwhelmed by this.

Older workers are concentrated in specific, low-paid occupations, such as security guards and care workers, that are seen as suitable for older people and which younger people do not wish to do. Such “occupational segregation” based on age is a form of discrimination.

What is more, older workers who are re-employed are often placed in social activity roles and may receive employment placements for only short periods of time. Under the Senior Employment and Social Activity Support Program, a national re-employment program supported by the Ministry of Health and Welfare, 71 percent of placements in 2022 were for voluntary, public service social activities and not salaried employment. The average length of employment placements under the program was just 4.6 months.

Human Rights Watch found that together, these three policies—forcing people to retire, paying them less because of their age, and moving them into lower-paid, more precarious, and often more physically demanding work—violate older people’s rights to work and non-discrimination. They also reinforce negative, ageist attitudes about older people’s abilities and place in society in South Korea today.

These problems are compounded by an inadequate social security system that does not meet human rights standards. Unemployment benefits for people 50 and older are limited to a maximum of 270 days, but people forced to retire at 60 may have to wait up to five years before they are eligible for the National Old Age Pension or Basic Pension. In 2023, only 40 percent of people 60 and older received a National Old Age Pension. Sixty-seven percent received the Basic Pension, which provides financial support for people 65 and older on low incomes, including those on low pension incomes from the National Old Age Pension.

Monthly payments under both pension programs are low. The National Old Age Pension was just 27 percent of the Seoul Metropolitan Government’s living wage and 31 percent of the national minimum wage in 2023. The Basic Pension was just 16 percent of the national minimum wage in 2024.

With a relative poverty rate of 38 percent of people 65 and older, those on low incomes may be eligible, irrespective of age, for income, medical, and housing support through the Basic Livelihood Security Program.

In 2023, 1.2 million people 60 and older received support under this program. Income support is available to those whose income is 32 percent or less of the national median income, and medical and housing assistance to those living on 40 and 48 percent or less respectively, all below the relative poverty line of 50 percent of the national median income. This means that some people below the relative poverty line, but above the eligibility thresholds, will not receive support under this program.

South Korea should take steps to meet its obligations under international human rights law and enable those older people who wish to continue working to do so on an equal basis with others.

Such steps include the National Assembly abolishing the mandatory retirement age and the peak wage system and ensuring all differential treatment based on age is subject to justification tests to make sure it is not discrimination. It should adopt a comprehensive anti-discrimination law to provide equal protection against all forms of discrimination, including age-based discrimination against older people, and a duty to eliminate ageism.

The Ministry of Health and Welfare should review re-employment programs to ensure older people have access to employment opportunities in all sectors and on an equal basis with others. It should also review whether the Basic Pension, the National Pension System’s Old Age Pension, and other social security entitlements are adequate to guarantee older people an income of at least equivalent to a living wage, and ensure it is available to everyone.

To the National Assembly

Remove article 4(5) of the Act on Prohibition of Age Discrimination in Employment and Elderly Employment Promotion, which allows exceptions to the prohibition on age discrimination without reasonable grounds, so that all differential treatment based on age in employment is subject to justification on reasonable grounds.

Abolish the mandatory retirement age of 60 or older by removing article 19 of the Act on Prohibition of Age Discrimination in Employment and Elderly Employment Promotion.

Amend article 21 of the Act on Prohibition of Age Discrimination in Employment and Elderly Employment Promotion to prohibit employers from imposing less favorable working conditions on older workers because of their older age.

Amend article 6.3 of the Act on the Protection of Temporary Agency Workers to limit the time workers age 55 and older may be employed under temporary agency contracts so that the same limits exist for older and younger workers.

Abolish the peak wage system.

Adopt a comprehensive anti-discrimination law that provides equal protection against all forms of discrimination, including age-based and other forms of discrimination against older people, and codifies a government duty to eliminate ageism.

Amend article 11 of the Constitution to include age as a prohibited ground for discrimination in political, economic, social, or cultural life.

To the Ministry of JusticeTo the Ministry of Employment and Labor

Support employers to retain older workers, including by ensuring employers provide ongoing training and professional development opportunities for older workers to maintain and enhance their skills, and programs to promote better health.

Require employers to introduce flexible or gradual retirement programs for those who wish to gradually retire from work, without using a peak wage system or a mandatory retirement age.

Prohibit, and enforce punitive measures against, employers imposing less favorable working conditions on older workers because of their older age.

Conduct a campaign to raise awareness of workplace discrimination against older workers and its harms, including derogatory language and stereotypes about productivity based on older age; promote positive attitudes about older people’s abilities to work and place in society; and end the culture of workplace discrimination against older workers.

Review and adjust the national minimum wage so that it provides an income of at least a living wage.

To the Ministry of Health and Welfare

Review employment programs to ensure older people have access to paid employment opportunities in a wide range of sectors on an equal basis with others.

Amend the unemployment benefit and other social security programs to ensure older people who are forced to retire or cannot find work before they are eligible for the National Old Age Pension and/or Basic Pension receive an income of at least equivalent to a living wage.

Amend the National Old Age Pension, Basic Pension, and other social security programs to ensure they are adequate to guarantee older people an income of at least a living wage.

Ensure that everyone has access to social security without interruption, including when transitioning between work, or from work to retirement.

Human Rights Watch interviewed 34 South Korean workers, aged 42 to 72, between February and September 2024. The age listed for each interviewee is their age at the time of their interview. Legislation prohibiting age discrimination at work in South Korea defines “older people” as 55 and older and “middle-aged people” as between 50 and 54. However, we also interviewed people in their 40s to understand the experience of those under 50 who may also face discrimination related to their older age.

Of those interviewed, 7 identified as men and 27 as women. Interviewees worked in the public and private sectors, in transport, customer service, online services, cleaning, health care, finance, sport, education, publishing, advertising, and caregiving. Four were union representatives.

All interviews were in person in Seoul, except one that was online. Interviews were conducted in Korean with English interpretation, except two in English. Human Rights Watch obtained informed consent from all interviewees and used pseudonyms, indicated by given names and surname initials, as desired. Interviewees were not compensated.

In addition, Human Rights Watch consulted 41 Korean researchers, academics, human rights experts, union workers, an international journalist, and representatives of nongovernmental organizations (NGOs), including three staff of international NGOs. We also reviewed national legislation and reports in Korean and English produced by the government, academics, workers’ associations, the media, and international institutions.

Human Rights Watch did not investigate individual employers that implement age-based retirement policies in line with current domestic law and government policy. Instead, we documented how those laws and policies discriminate against older workers. Our research aims to support advocacy to reform the resulting system that allows this discrimination.

In February and March 2025, Human Rights Watch requested information on the impact of age-based employment policies from the South Korean Ministry of Employment and Labor, Korea Enterprises Federation, Korea Railroad Corporation (KoRail), Seoul Metro, and Seoul National University Hospital. The Ministry of Employment and Labor and KoRail responded on March 26, 2025, and the information they provided is reflected in the report. Korea Enterprises Federation declined to respond and referred Human Rights Watch to the Ministry of Employment and Labor.

In June 2025, Human Rights Watch provided the Ministry of Employment and Labor and the Ministry of Health and Welfare with a summary of its findings and invited their response. The Ministry of Employment and Labor responded on June 23, stating that they would consider the report’s findings when improving their policies. The Ministry of Health and Welfare referred Human Rights Watch to a number of its departments, but none had responded at time of writing.

Human Rights Watch also provided KoRail, Seoul Metro, and Seoul National University Hospital with a summary of its findings in June 2025 and requested information on their age-based employment policies. Seoul National University Hospital declined to respond. KoRail and Seoul Metro responded on June 9 and June 20, respectively. The information they provided is reflected in the report.

At the time of the interviews, 1,000 Korean Republic Wons (KRW) were worth US$0.75, and one US dollar (US$) was worth KRW1,335.

Population Ageing

South Korea has one of the highest life expectancies in the world. Girls born in 2025 can expect to live until they are 87; boys until they are 81. South Korea also has the lowest fertility rate in the world. High life expectancy and the low fertility rate contribute to South Korea’s population ageing, with 20 percent of the population age 65 and older in 2024. Among women, 22 percent are age 65 and older; for men that figure is 18 percent.

Dual Labor Market“Regular” and “Non-regular” Work

South Korean law recognizes both “regular” and “non-regular” work within the labor market.

Statistics Korea defines non-regular work as: limited-term, fixed-term, part-time, or on-call work; special types of employment; temporary agency work; subcontracted work; and home-based work. Trade unions also include day labor as non-regular work. People work under non-regular working conditions across a wide range of industries and occupations: from health and social work to manufacturing, and from professionals to machine operators.

Regular jobs are those with permanent, full-time contracts, and together with non-regular work contribute to South Korea’s dual labor market structure.

Statistics Korea data shows the proportion of non-regular workers is rapidly rising, from 32 percent of wage earners in 2015 to 38 percent in 2024, the majority of whom – 57 percent – were women. Older workers are disproportionately represented among non-regular workers. In 2024, of the 8.5 million non-regular workers, 2.8 million (33 percent) were 60 and older, and 1.6 million (20 percent) were 50 to 59. In 2023, 69 percent of the 3.8 million older people earning a wage were employed in non-regular work, nearly twice the proportion of workers of all ages, at 37 percent.

Non-regular jobs are often lower paid than regular jobs. In 2022, the monthly wage of older people in non-regular jobs was estimated to be half of that of older people in regular jobs, based on figures from Statistics Korea.

A large number of older people work and do not earn a regular wage. Of the 14.2 million people 60 and older in 2024, 2.1 million were self-employed. Half a million were family members working without wages or a contract for a family business—known as “unpaid family work”—making up 51 percent of all unpaid family workers.

Company Size

Company size is also a prominent feature of the labor market, with labor statistics often presented by the number of full-time employees. Large companies, including family-owned conglomerates known as “chaebol,” have dominated South Korea’s economic growth and pay higher wages than small- and medium-sized enterprises. Working conditions are also affected by company size, for example working hours, with those in companies with over 300 full-time employees least likely to work over 52 hours per week.

Large companies include those in the textile, steel, car, and electronics industries. In 2025, 3.4 million people worked in companies with more than 300 full-time employees, while 16.7 million worked in companies with fewer than 300 full-time employees. In 2024, 885,953 people 55 and older worked in large companies.

Responsibility for Protection Against Discrimination at Work

The Ministry of Employment and Labor’s promise to the people of South Korea is a “country where the people fulfill themselves in desired positions.” As part of its mission, the ministry aims to “strengthen employment assistance tailored to age and gender” and foster “a discrimination-free workplace.”

South Korea’s constitution guarantees nondiscrimination and the right to work to all citizens, and the Labor Standards Act guarantees equal treatment in employment on the grounds of gender, nationality, religion, and social status. Promotion of nondiscrimination at work is central to the Ministry of Employment and Labor’s employment policy. To this end, the Act on Prohibition of Age Discrimination in Employment and Elderly Employment Promotion prohibits age discrimination in all aspects of employment, including retirement. The Welfare of Senior Citizens Act states that national and local government shall provide job opportunities for older people. The National Human Rights Commission of Korea Act established the National Human Rights Commission of Korea to carry out inquiries into and find remedies for violations of human rights guaranteed under the Constitution and discriminatory acts, including those based on age.

The National Assembly, South Korea’s 300-member elected legislature, has the power to enact, amend, and abolish national laws. Local governments, at city, province, county, and district level, are responsible for local administration under the Local Autonomy Act. This includes responsibility for the promotion of local industry and support for small and medium enterprises.

The South Korean judiciary operates a three-instance trial system through district courts, high courts and finally the Supreme Court, the country’s highest court.

Retirement

“Retirement” in the context of work is generally understood as when people, usually older, leave a career or long-serving job. Retirement can also mean the period of life after leaving a career or long-serving job. Statistics Korea reported in 2024 that 8 percent of “household heads and their spouses” in South Korea felt they were well-prepared for retirement, and 53 percent that they were not well-prepared.

Long tenure and lifetime employment were prized in South Korea for providing stability and loyalty to an employer but became less common after the 1997-98 economic crisis. Statistics Korea reported that, in 2024, the average age at which people 55 to 79 left their main job—the job with the longest duration in one’s lifetime—was 53. For those 55 to 64, it was 49.The reasons workers gave for leaving included layoffs and businesses closing (29 percent), ill health (19 percent), and family responsibilities (16 percent).

Other contributing factors to this “early” retirement from main jobs include “honorary retirement,” when employers encourage or pressure employees to accept incentives to retire before the mandatory retirement age, and mandatory retirement age itself—the age at which a worker has to retire from their job, and which is discussed below.

While some people stop working completely when they retire from their main job, many (69 percent) want or need to continue working. The average maximum age people want to work until is 73.

Pensions

South Korea has several overlapping pension programs with different eligibility criteria and levels of payment.

Different Pension Systems

Type

System

Eligibility

Public

National Old Age Pension

All citizens except government employees, military personnel, private teachers, and special post office employees

Basic Pension

People 65 and older on low incomes

Special Occupational Pension

Government employees, military personnel, private teachers, and special post office employees

Employer

Severance Payment

Private sector employees

Retirement Pension

Private

Personal Pension

All citizens – voluntary

South Korea introduced a National Pension System in 1988, expanding its coverage from workplaces with 10 or more full-time employees to all workplaces by 2006. Government officials, military personnel, private school teachers, and special post office employees are eligible for separate occupational pension plans.

The National Pension System, which encompasses old age, disability, and survivor pensions, is partly funded by contributions (58 percent in 2023) and partly by returns on investments of a National Pension Fund (42 percent). The contribution rate for the program is 9 percent of income. Employees contribute 4.5 percent while their employers contribute the other 4.5 percent. People who are not eligible to join through their workplace or because they are not employed can apply to join as an individual on a “voluntary” basis and pay the full 9 percent themselves.

The Basic Pension provides financial support for people 65 and older on low incomes, including those on low pension incomes from the National Old Age Pension, but not those in receipt of special occupation pensions. To be eligible for the Basic Pension, the older person’s income must fall below an income threshold which is set by the Minister of Health and Welfare to cover at least 70 percent of those aged 65 or older. In 2025, the threshold below which an older person’s monthly income must fall to be eligible for the Basic Pension was KRW2,280,000 (US$1,600) for a single person and KRW3,648,000 ($2,500) for a couple.

Other pensions include government employee pensions and private sector employee pensions. Private sector companies must provide a severance payment program when someone who has worked for at least one year, leaves. If the majority of employees agree, these can be converted into retirement pension programs.

If I still worked in a major company, I might not have a job at this age since clients and co-workers would think I was too old.

—K. Soo Jin, 43, worker in a small online advertising agency, Seoul, August 28, 2024

Ageism toward Older Workers

Workplace culture in South Korea reflects wider social norms around hierarchy and respect linked to social status and age. A strict ranking system is applied to job positions, and it is considered inappropriate to manage someone older than oneself. In companies, the more formal, polite level of speech in the Korean language (jondaetmal), used with strangers, older people, and in formal situations, is always used when speaking to superiors or to colleagues who are older. The less formal level (banmal), usually used among friends and family and in casual settings, can be used by managers with those they manage or with younger colleagues. But “there is a double standard in Korea,” said Gwon Oh Hoon, 52, a labor attorney and education director at Gikjang Gabjil 119, an organization that works to combat workplace bullying. “People respect older people – and they despise them.”

Older workers told Human Rights Watch about derogatory language colleagues or clients used toward or about them based on their older age. Language that perpetuates negative stereotypes and prejudices about older age and older people is verbal abuse and a form of ageism. The World Health Organization has defined ageism as the stereotypes (how we think), prejudice (how we feel), and discrimination (how we behave) toward people based on their age.

Kkondae is a term used to refer to someone, typically as an insult, who is authoritarian, condescending, or rigid in their thinking, and can be used to refer to someone of any age. While rigid and hierarchical workplaces may foster kkondae attitudes, because the term is often used to refer to older people, it can contribute to stereotyping older people as outdated or unwilling to change. C. Sung Ho, 57, has worked for a public corporation for 29 years. “Before we used to guide or correct [younger colleagues],” he said. “But now they think we are old kkondae or useless.”

Older women may be referred to as ajumma, a frequently derogatory term meaning a married or middle-aged woman. L. Mi Kung, 72, has been a care worker for 25 years in a sector dominated by older women workers. She described disrespectful relationships with clients’ families. “Families look down on us and mistreat us,” she said. “They don’t call us by the name for a care worker but call us ajumma.”

The United Nations Committee on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities states that the use of words that perpetuate “difference and oppression,” including based on age, is harassment, a form of discrimination that creates hostile environments where people feel offended, degraded, or humiliated. The World Health Organization and the International Labour Organization have recognized that discrimination and harassment at work, including related to age, pose a risk to and undermine mental health. Studies show that workplace age discrimination increases job-related stress and undermines older workers’ mental health.

Although the Korean word for older person, noin, is not in itself derogatory, it has a negative connotation. J. Mi Sook, 53, who works in human resources for a large company, said: “It means being useless, that you can’t do anything.” She said that where she works, younger people say older colleagues are “old-fashioned and can’t keep up with younger people’s mindset.”

A. Hyun Joo, 47, was laid off from her job with an online service company when she was 46. She was still not working when she spoke to Human Rights Watch and was worried she would never get another job. “I feel too old to be re-employed,” she said. “Companies consider future employees’ age and compensation when they choose people. If, at age 47, I go to a company where the majority of workers are in their 20s and 30s, I don’t think they’d hire me although I have years of experience. They’d think, why hire an older person?”

Older Workers Seen as a “Burden”

In a 2021 survey, Korea Enterprises Federation found that 58 percent of companies surveyed felt that employing people beyond the age of 60 would be a burden because of older workers’ declining productivity, the additional salary-related costs of continuing to employ older workers, and an unspecified negative impact it would have on hiring younger workers.

A number of studies have identified South Korea’s seniority wage-based system as a key reason companies do not wish to employ older workers. Under this system, introduced during South Korea’s early industrialization period to recruit and retain skilled workers, companies pay young, entry-level workers low wages with the promise that these will increase with the number of years they work. However, according to Korea Labor Institute, a public research institution, only 20 to 30 percent of companies were still using a seniority wage-based system in 2023 and had instead moved to a wage system that takes into account performance evaluation results and job performance ability, in addition to years of service. Some employers also use a “peak wage” system, discussed below, where older workers’ wages are reduced in the three to five years leading up to their mandatory retirement in order to lower the cost of continuing to employ them.

Policymakers, too, have contributed to this hostile working environment for older workers. In February 2024, 38 members—one-third—of the Seoul Metropolitan Council, the capital’s local government legislative body, proposed exempting people 65 and older from the Minimum Wage Act in the belief that employers would be more likely to hire them if they were paid less than younger workers. At time of writing, the sub-committee to which the proposal was submitted had not discussed it further, following trade union protests that the exemption discriminated against older workers.

South Korea’s Act on Prohibition of Age Discrimination in Employment and Elderly Employment Promotion prohibits age discrimination without reasonable grounds in all aspects of employment.

International human rights law defines discrimination as any distinction, exclusion, restriction, or preference or other differential treatment that is directly or indirectly based on prohibited grounds of discrimination and which has the intention or effect of nullifying or impairing the recognition, enjoyment, or exercise, on an equal footing, of all rights or freedoms.

International treaties listing specific prohibited grounds of discrimination include “or other status.” The inclusion of “other status” indicates that other grounds may be incorporated in this category, which may include age. UN treaty bodies have recognized age as an “other status.” “Differential treatment” based on stereotypes because of age is discrimination. States can only treat people differently because of their age or any other grounds if they can justify such differential treatment as reasonable and objective. To be reasonable and objective, differential treatment must:

Have a legitimate aim that is compatible with international human rights standards;

Be proportionate, meaning the harmful impact of the differential treatment must not outweigh benefits in relation to “the aim sought to be realized”; and

Be necessary, meaning alternative, less harmful actions must be considered first.

Differential treatment is discrimination if it fails any one of these three tests—namely it does not have a legitimate aim that is compatible with international human rights standards, or it causes harm disproportionate to the benefits of the aim, or it is unnecessary because less harmful alternatives could be used.

Mandatory Retirement Age

It’s an infringement of human dignity. Just because I’m older, I can’t work where I’ve worked my entire life.

—Gwon Oh Hoon, 52, attorney, Seoul, August 27, 2024

In 2013, the average age set by employers at which full-time workers had to retire from companies with 300 or more employees was 58. This was based on the practices of 2,854 companies and affected 2.4 million workers. In the same year, the National Assembly amended the Act on Prohibition of Age Discrimination in Employment and Elderly Employment Promotion to include a minimum age that employers had to respect when setting their workers’ mandatory retirement age.

A mandatory retirement age is the age at which a worker is forced to retire from their job. It is “mandatory” for the worker because the worker must stop working when they reach a certain age regardless of whether they wish or have the ability to continue working. Depending on the law or policy in place in any given country, employers may be required to use a mandatory retirement age, or they may be permitted to use one if they wish. In either case (whether the employer is required or permitted to use a mandatory retirement age), once set, the retirement age is still mandatory for the worker.

Mandatory retirement ages should not be confused with pension eligibility ages, which refer to the age at which someone is eligible to receive a pension.

The Act on Prohibition of Age Discrimination in Employment and Elderly Employment Promotion allows employers to set a mandatory retirement age “under labor contracts, rules of employment, collective agreements, etc.” The 2013 amendment to the act stated that employers, if they use a mandatory retirement age, “shall set the retirement age of workers at 60 years of age or older” so that they could not set their mandatory retirement age at 59 or younger. The amendment came into force in 2016 and applies in both the public and private sectors.

In the public sector, the mandatory retirement age of 60 or older applies to full-time employees of national and local governments, as well as public institutions and corporations. The mandatory retirement age of public officials is 60 under the State Public Officials Act. However, the mandatory retirement age of some public officials, such as firefighters and public teachers, is set under legislation specific to their professions and may be 60 or older.

In the private sector, the mandatory retirement age of 60 or older has applied to large companies employing 300 or more regular workers (who have permanent, full-time contracts)since 2016 and to those with fewer than 300 regular workers since 2017. Private sector employers are not obligated by the law to apply a mandatory retirement age, but those who choose to, must set it at age 60 or older. In 2023, 95 percent of companies with 300 or more employees had a mandatory retirement age, the average age of which was 60, the lowest possible age. At that time, 3.1 million people were working on permanent contracts in companies with 300 or more employees.

While the mandatory retirement age forces older workers to retire from their main or career jobs, it does not prevent them from going on to seek work with employers who do not use a mandatory retirement age. In 2023, only 21 percent of companies with 299 or fewer employees had a mandatory retirement age, the average age of which was 61.5. At that time, 13.6 million people were working on permanent contracts in companies with 299 or fewer employees.

Korea Enterprises Federation attributed this difference between large and small companies in setting mandatory retirement ages to solving labor shortages since the smaller the company, the more likely they are to be affected by labor shortages. Smaller companies are less likely to apply a mandatory retirement age as they wish to retain older workers, the federation stated. Mandatory retirement ages do not apply to non-regular workers, including those on fixed-term or temporary contracts, and day laborers.

Incompatible with International Human Rights Law

The Act on Prohibition of Age Discrimination in Employment and Elderly Employment Promotion prohibits age discrimination carried out without “reasonable grounds” in all aspects of employment, including retirement.

However, the act allows four specified exceptions to this prohibition where differential treatment “shall not be deemed age discrimination.” These exceptions were inserted into the act in 2008 and are where:

Age limits are “inevitably” required to carry out certain jobs.

Salary and benefits are offered linked to the employee’s length of service.

Retirement ages are set under contracts, rules of employment, or collective agreements.

Measures are taken to maintain or promote employment of certain age groups.

By naming these as exceptions to the general prohibition of age discrimination in employment without reasonable grounds, the law removes the need for employers to justify any differential treatment in these areas. This includes setting mandatory retirement ages. Because of this permissible exception to the prohibition on age discrimination, the National Assembly was able to amend the act in 2013 to include the age from which employers can set their mandatory retirement age without requiring them to justify it on reasonable grounds.

International human rights law provides that differential treatment is not discrimination only if it can be justified as reasonable, objective, and having a legitimate purpose. Differential treatment cannot be based on stereotypes. By allowing exceptions to the prohibition of age discrimination, the Act on Prohibition of Age Discrimination in Employment and Elderly Employment Promotion removes certain differential treatment, including the use of a mandatory retirement age, from requiring such justification. This means that workers are not protected against age discrimination in relation to the use of a mandatory retirement age, as well as the other three named circumstances.

South Korea has an obligation under the international human rights treaties that it has ratified to ensure that its laws, both as drafted and implemented, do not discriminate or permit discrimination. Under the Labor Standards Act, employers are prohibited from dismissing or laying off workers without “justifiable cause.” However, by making all 60 or older mandatory retirement age programs lawful and exempting them from justification as reasonable, the Act on Prohibition of Age Discrimination in Employment and Elderly Employment Promotion allows differential treatment regardless of whether it is justifiable or not. This is incompatible with applicable international human rights standards on equality and non-discrimination.

Under the Labor Standards Act, employees are also guaranteed the right to request a remedy if they are unfairly dismissed. However, the exception from the prohibition of age discrimination without reasonable grounds denies older workers the right to make a claim of unfair dismissal due to age discrimination when they are subjected to a mandatory retirement age, or to seek remedy and redress for it. International human rights law guarantees everyone the right to seek justice for a violation of their rights, including the right to work.

Human Rights Watch could find no cases or investigations by the National Human Rights Commission of Korea on whether the use of a mandatory retirement age is discrimination on the basis of age or is justifiable on reasonable grounds. Human Rights Watch could also find no cases in which the Supreme Court of Korea examined whether the use of a mandatory retirement age was discrimination on the basis of age or justifiable on reasonable grounds.

South Korea’s constitution guarantees equality. However, there have been very few cases on the mandatory retirement age before the Constitutional Court. In 2015, the court dismissed a claim that the different entry-into-force dates of the mandatory retirement age of 60 or older for companies with more than 300 employees in 2016 compared to that for companies with fewer than 300 employees in 2017 was a violation of the constitutional guarantee of equality. The case did not address whether the mandatory retirement age itself was discriminatory. In 2002, before mandatory retirement ages were made an exception to the prohibition of age discrimination without reasonable grounds, the court dismissed a challenge that a mandatory retirement age was a breach of the constitutional guarantee of equality, stating that “age, unlike sex, religion, or social status, is not enumerated under article 11 of the Constitution as a factor not to be used as a basis for differential treatment.”

By making mandatory retirement at 60 or older lawful and exempt from justification, people affected have no apparent means to make a claim of age discrimination or seek redress under South Korea’s laws.

Causes Disproportionate Harm

Differential treatment based on age is discrimination if it causes disproportionate harm, where the harm it causes outweighs any benefits in relation to its aim.

The Ministry of Employment and Labor stated that the aim of having a “retirement age” starting at 60 was to create “a social environment where the older people who want to work longer can do so.” The aim of setting the retirement age at 60 or older was to reduce early retirement and keep older people in their main jobs until at least 60. In 2013, when the National Assembly amended the law to include a retirement age of 60 or older, the average age at which people left their main job according to the Ministry of Employment and Labor was 53, and early retirement practices such as honorary retirement were common, particularly in white-collar jobs in large companies. While the labor ministry and law refer to a “retirement age,” by exempting retirement ages from the prohibition of age discrimination, employers can force workers to stop working at a certain age regardless of whether they wish or have the ability to continue working, which makes the retirement age mandatory for the worker.

Limited Benefit to Older Workers

Since coming into force in 2016, the mandatory retirement age of 60 or older has had limited impact on people working longer in their main jobs.

Statistics Korea data shows that between 2014—two years before it came into force—and 2023, the average age of retirement from a main, lifetime job stayed the same, at 49.4. Korea Labor Institute has cautioned against reliance on this figure since it excludes older people who were working at the time of the survey, combines wage jobs and self-employed jobs, as well as full-time jobs and temporary jobs, and could include people who left their main job at any age, not just when they were older. The institute’s own analysis shows that among workers 60 and older, there was a minimal increase in the average age of retirement from their main job, from 54.1 in 2016 to 54.9 in 2023. In 2024, Statistics Korea reported that the average age at which people 55 to 79 left their main job was 53. For those 55 to 64, it was 49.

Human Rights Watch wrote to the Ministry of Employment and Labor, KoRail, Korea Enterprises Federation, Seoul Metro, and Seoul National University Hospital between February and June 2025, requesting information on the impact of the mandatory retirement age on keeping older workers in their main jobs until 60 or older and other benefits since it came into force in 2016. Korea Enterprises Federation declined to respond and referred Human Rights Watch to the Ministry of Employment and Labor. Seoul National University Hospital declined to respond.

The Ministry of Employment and Labor responded on March 26, 2025, sharing a report that it had commissioned Korea Labor Institute to produce and publish in 2020. The institute found that the impact of the mandatory retirement age of 60 or older on keeping older workers in their jobs for longer depended on a number of factors, including age, the presence of strong unions, and company size:

The average length of time that 55- to 64-year-old workers who had already retired had spent in their main job, and the age at which they had retired from it, had not significantly changed. However, the age at which 53- to 62-year-old workers retired was increasing.

The impact on increasing the time older workers worked for was greater in the public sector, which had previously guaranteed retirement age, than in the private sector, and greater in companies with unions with effective bargaining powers.

Employment of older workers increased in small- and medium-sized companies where there was already a higher proportion of older workers; employers retained older workers as it was hard to hire new workers; and employers did not reduce older workers’ already low wages. Larger companies, on the other hand, attempted to reduce the number of older workers by offering honorary retirement programs and vocational training to prepare them for work elsewhere.

KoRail responded on March 26, 2025, saying it had no information on the benefits of the mandatory retirement age but providing data on the number of workers retiring each year from 2021 to 2024. Their data showed that of all workers retiring, the proportion retiring at the mandatory retirement age had decreased while those retiring earlier due to honorary retirement or other reasons such as resignation had increased over the four-year period.

Seoul Metro responded on June 20, 2025, but did not provide information on the benefits of the mandatory retirement age.

Based on this data and our interviews, Human Rights Watch did not find evidence indicating that the mandatory retirement age of 60 or older has significantly extended the time older people remain in their main jobs, which was the government’s stated goal in adopting this legislation.

Harm to the Mental Health of Older Workers

The older workers whom Human Rights Watch interviewed said work gave them a sense of purpose, belonging, and self-fulfillment. Yang Myung Ju, 55, is facing mandatory retirement at 60 from her part-time job in customer service in a call center. She works nine hours a day, five days a week, and takes pride in her work despite finding the work stressful and the pay low at KRW1.5million (US$1,125) per month after tax. “I know what I’m doing, I know I do it right, and that gives me a kind of pride,” she said.

Being forced to retire because of age removes this sense of belonging and purpose, and the dignity older workers can get from work. G. Young Soo, 59, has worked for 36 years for an insurance company. He joined the company at 23 as an office worker and has worked as a branch director, a sales team leader at the company’s headquarters, and a team leader conducting training. “I feel a sense of reward, and I’m happy to work there,” he said, but is facing mandatory retirement in one year.

Older workers forced to retire described to Human Rights Watch the fear, anxiety, loss of belonging, purpose and dignity, and financial worries, all indicating significant emotional and psychological distress and harm to their mental health and well-being. The World Health Organization recognizes that “a sense of confidence, purpose and achievement” at work can protect mental health, while job insecurity, exclusion, and discrimination pose risks to it. A study in South Korea looked at the effects of retirement on depressive symptoms and found that the negative effects of completely exiting the workforce before the average age, which the study cites as 72.3 in South Korea in 2018, increased as the retirement age lowered, and was greater among younger people forced to retire.

Y. Kyung Hee, 59, is a professor in a public research institute where she has worked for 27 years. She is also facing mandatory retirement in one year. For her, work is not only a way to earn money but also something meaningful she does every day. “I’m worried about the mandatory retirement age as I can’t imagine not going to work every day,” she said. “I feel afraid.”

After working as a nurse for 36 years, D. Young Sook, 59, is anxious about loneliness and isolation after she is forced to retire at 60. “I can’t imagine myself being out of this organization,” she said. “It would feel like standing by myself on a windy road.”

In research on the effects of the mandatory retirement age of 60 or older, commissioned by the Ministry of Employment and Labor, Korea Labor Institute found that workers may experience significant psychological distress as they struggle to adjust to being dismissed by companies they were committed to. Older workers told Human Rights Watch about the injustice of being forced to retire when they were able to continue working. Kim Dai Hun, 63 and forced to retire at 60 from his job as an office worker at Seoul Metro, a local public corporation, said the mandatory retirement age was not fair. “Compared to the past when [South] Korea was economically poor, we are now healthier compared to our age, but we have to retire way too early,” he said. “If there were no mandatory retirement age, those who can work longer would not be deprived of the right to choose [whether to continue working or not].”

Financial Harm to Older Workers

Mandatory retirement also forces people into lower-paid, more precarious non-regular work, despite the labor ministry’s aim to reduce non-regular employment, for example by directly employing previously sub-contracted public sector workers. Some forced retirees told Human Rights Watch that they found employment doing a similar job but for a sub-contractor, for lower wages, or on short, fixed-term contracts. Park Hae Chul, 58, started working for the Korean Railroad Corporation (KoRail), a public corporation and national railway company, in 1994 and is executive committee chair of the Korea Rail and Metro Unions’ Council. He said that KoRail has a mandatory retirement age of 60. “When people retire from the company, around 30 percent of them go to outsourcing companies for KoRail and do the same work, but their income is lower.”

In 2024, the Ministry of Employment and Labor reported that the average monthly wage of workers 60 and older was 29 percent less than that of workers 59 and younger.

Some workers are disproportionately disadvantaged if employers set different mandatory retirement ages for different jobs. As a nurse, D. Young Sook must retire at 60. However, the mandatory retirement age for doctors and medical school professors at the hospital where she works is 65. This policy risks discriminating based on gender, as nurses in South Korea are predominantly women and doctors predominantly men.

In addition, under a peak wage system, workers whose wages are reduced in the three to five years leading up to their mandatory retirement also experience financial harm before they are forced to retire. The financial harms of these wage reductions prior to the mandatory retirement age exacerbate the financial harms of mandatory retirement itself.

Human Rights Watch wrote to KoRail, Seoul Metro, and Seoul National University Hospital in June 2025 asking for information on the aim and scope of their mandatory retirement age policies, processes they followed to assess whether the retirement ages would not be discriminatory in violation of basic rights, and how they periodically review them. Seoul Metro and KoRail responded that their mandatory retirement age for employees was 60, with KoRail, additionally setting the age for “specialists” under separate employment contracts. Neither provided information on assessments or periodic reviews of mandatory retirement age policies. Seoul National University Hospital declined to respond.

Based on this evidence and our interviews, Human Rights Watch considers the mandatory retirement age to be disproportionate, with the harm it causes outweighing any benefit to its stated aim of keeping people in their main jobs until 60.

Is Unnecessary

The Ministry of Employment and Labor has a policy to subsidize businesses that re-employ workers when they reach the employer’s mandatory retirement age, raise the retirement age, and/or abolish the mandatory retirement age. The ministry says these subsidies are incentives for employers to retain older workers in their main jobs for longer. The need for such incentives, including for abolishing mandatory retirement ages, can be interpreted to mean that the ministry itself believes that the mandatory retirement age of 60 or older is not keeping older workers in their main jobs—the ministry’s original aim—and is not necessary.

Alternative measures are available for retaining older workers in their main jobs that do not force them to retire at 60 or older. These include ongoing training and professional development opportunities to maintain and enhance skills; flexible or part-time work for those who wish to reduce their hours or transition toward retirement at a time of their choosing; or programs to support better health.

Furthermore, the alternative of abolishing the mandatory retirement age and enabling workers to continue working on their current terms and conditions if they wish to is less harmful to older workers than re-employing them after mandatory retirement on lower-paid, more precarious temporary contracts, as discussed in the section below on re-employment policies.

“Peak Wage” System

Older people are mistreated and discrimination against them is rampant. And in the middle of that is the peak wage system.

—Park Hae Chul, 58, railway engineer, Seoul, August 30, 2024

The “peak wage” system reduces workers’ wages at a certain age or freezes them so that they do not rise any further. This system is a way to reduce the cost of employing older workers under a seniority-based wage system where salaries rise in line with length of service. Some companies introduced peak wage systems in South Korea in the mid-2000s, reducing older workers’ salaries in exchange for guaranteeing their employment until retirement age.

When the government amended the Act on Prohibition of Age Discrimination in Employment and Elderly Employment Promotion in 2013, stipulating that the mandatory retirement age should be 60 or older, it also legislated for employers to restructure their wage systems “in consideration of the conditions at the relevant business or place of business.” With more people expected to work until 60, the Ministry of Economy and Finance produced guidelines in 2015 to accelerate the adoption of a peak wage system among public institutions to reduce workers’ wages in the three to five years before their mandatory retirement age. At the same time, the Minister of Employment and Labor said that the seniority wage system, where wages increase with each year worked, “must ultimately be reformed to focus on job competency and performance.”

The peak wage system could be applied where the retirement age had not changed (retirement age maintenance), where the retirement age had been raised (retirement age extension), and where re-employment occurs after retirement age on a contract on a lower wage.

The aim of the peak wage system was to create new jobs for younger employees in order to increase productivity. The guidelines stipulated that, for every employee whose employment was extended until 60, a younger employee should be hired in an entry-level position. The savings made from reducing the salary of the older employee would be used to pay for the younger employee. Institutions were free to decide the exact rate and duration of the salary reductions.

The government also made adoption of the peak wage system part of public institutions’ performance evaluation and considered subsidizing each new employee hired. By the end of 2015, all 313 public institutions had decided to adopt it. Alongside extending mandatory retirement ages by an average of 2.5 years, they reduced salaries in the 3 years before mandatory retirement to about 83 percent, 77 percent, and finally 70 percent of the original salary in the final year before mandatory retirement.

While not compulsory for private companies, the government encouraged them to adopt the peak wage system. By 2022, 51 percent of private companies with a mandatory retirement age and more than 300 employees, and 21 percent of private companies with fewer than 300 employees had adopted it.

The courts in South Korea have not treated the peak wage system as an exception to the prohibition on age discrimination without reasonable grounds. Under the Labor Standards Act, employers are prohibited from reducing the wages of workers without “justifiable cause.” In 2022, South Korea’s Supreme Court considered the following in deciding whether use of the peak wage system is reasonable or discriminatory: the legitimacy of aim and necessity, degree of disadvantages to older people, whether reduced wages meant reduced workload or intensity of work, and whether expenses saved were actually used for the original purpose.

The Supreme Court determines the invalidity of a company’s peak wage system on a case-by-case basis. For example, in May 2022, the court ruled that reducing labor costs and increasing performance was not a justifiable reason for a research institute to reduce the wages of workers from age 55 to their existing mandatory retirement age of 61, and that no measures had been taken to offset the disadvantages to the older workers affected. However, in March 2024, the court ruled that a bank’s peak wage system was justifiable because its aim of hiring experienced workers under an efficient labor cost system was reasonable, and because the reduction in wages was accompanied by an extension of the mandatory retirement age. Consequently, the court said that, although those affected worked for an extra year, the overall loss to their base salary over the period the peak wage system was applied—10 percent—was not a significant disadvantage coupled with a reduction in hours and duties and other incentives offered.

In a review of lawsuits on the peak wage system, the Korea Economic Daily found that, after the Supreme Court first ruled that the peak wage system could be discriminatory in May 2022, the number of cases doubled from 111 in 2022 to 213 in 2023. They noted a particular rise in cases initiated in the lower courts, from 80 in 2022 to 187 in 2023.

Of 17 discrimination complaints on the peak wage system to the National Human Rights Commission of Korea between 2022 and 2024, the commission dismissed all eight where the applicants’ wages were reduced in the years leading up to a retirement age that had been extended to 60 or older, often citing the additional years of work as a benefit to the worker despite the reduced pay. In contrast, it only dismissed three of the nine complaints when applicants’ wages were reduced in the lead-up to a retirement age of 60 or older that was unchanged.

Based on an Ageist Stereotype

International human rights law prohibits treating people differently based on a stereotype, including ageism, as this constitutes discrimination.

The peak wage system aims to create new jobs for younger workers in order to increase productivity. Paying older workers less to free up wages to employ younger ones, in order to increase productivity, assumes that older workers are less productive because of their age. The Ministry of Employment and Labor based the peak wage system on the concept that it would contribute to increased productivity by reducing employees’ wages in line with their “reduced productivity and work performance” after a certain time, and hiring younger employees with the money saved.

Studies on age and productivity in South Korea have shown that ageing is not associated with lower productivity at work. Concluding that all older workers are less productive than younger ones is an ageist stereotype. Kim Ki Hee, 60, a care worker, said: “People’s physical age and capabilities are different, and you can’t limit their ability to their age.”

Since the peak wage system is based on this ageist stereotype, it is unjustifiable and is discriminatory.

Causes Disproportionate HarmGovernment Has Not Demonstrated the Benefit to Younger Workers

As mentioned, the peak wage system’s aim was to hire more younger workers. Meeting its intended aim is one of four tests the Supreme Court of South Korea uses to justify such differential treatment of older workers. In 2015, when all public institutions had decided to adopt the peak wage system, the youth employment rate (age 15 to 29) was 42 percent. In 2024, it had risen to 45 percent. However, despite the Ministry of Economy and Finance guidelines stipulating that a younger worker should be employed for each older employee whose employment is extended and wages reduced, Human Rights Watch found limited evidence to show the peak wage system has been a direct benefit to younger workers.

Findings in studies on the impact of the peak wage system on employment of younger workers published at different times using different data are inconsistent. One 2017 study of companies with more than 100 workers found that the peak wage system had no impact on youth employment. Another, in 2021, found that introducing a peak wage system had no long- or short-term effects on employment although it did decrease over time the number of regular workers and increase the number of non-regular workers, whose working conditions are generally less favorable. A third study in 2023 found an increase in the proportion of younger to older workers when the peak wage system was used, as well as a negative impact on the proportion of older workers where the retirement age had been extended.

The government’s original intention was to “closely review job creation under the new wage system.” Human Rights Watch wrote to the Ministry of Employment and Labor in February 2025 to ask for the results of its monitoring of job creation for younger workers. The ministry responded in March 2025 stating it did not have this information. For C. Jung Hoon, an insurance company union representative, the failure of the government to monitor whether companies are reducing the workloads of those subject to the peak wage system or using the money saved to hire younger workers, as it had committed to, gives rise to legal disputes between companies and workers.

Three employees in two public institutions and two in a private company who spoke to Human Rights Watch said that they had not observed their workplaces using the money saved to hire more younger workers.

Y. Kyung Hee, 59, has worked in a public research institute for 27 years. She said: “It’s not easy for the institution to hire younger people because we are a public organization and so there is [only] a certain number of people they can hire.”

Hyun Jung Hui, 58, has worked at Seoul National University Hospital, a special corporation, for 29 years, first as a midwife and then as a union representative. She said: “The peak wage system has no impact. We get a reduced salary, but the number of people the hospital hires is set. The money is not set aside by itself [to hire younger workers] but is just used for annual costs.” Human Rights Watch wrote to Seoul National University Hospital in February and June 2025 to ask for the results of its monitoring of job creation for younger workers with money saved from reduced wages under the peak wage system. The hospital declined to respond.

Seoul Metro informed Human Rights Watch that it introduced a peak wage system in 2015. However, the corporation said that if, in any given year, savings from reduced wages were insufficient to hire one younger employee for each 59-year-old worker placed under the peak wage system, it reduced the number of younger employees it hired, with approval from the Ministry of the Interior and Safety.

While private companies do not necessarily have fixed numbers of staff, their employees may face similar problems to those encountered by public employees. G. Young Soo, 59, expressed disappointment that his employer had not used the savings from his reduced wages to strengthen the company. “When the peak wage system was first introduced, the company promised to use the finance to hire younger workers. But if you look at the employment statistics [of the company] over the last five years, this is not true,” he said.

In February 2025, Human Rights Watch asked Korea Enterprises Federation for information on how its members and private sector businesses were monitoring the use of money saved under the peak wage system to hire younger workers. The federation declined to respond, saying that its request should be addressed to the Ministry of Employment and Labor.

Harm to the Mental Health of Older Workers

Being paid less because of older age can have a significant impact on older workers’ sense of dignity. Gwon Oh Hoon, 52, attorney, expressed feeling very frustrated. “I feel as I’m getting older, I’m becoming useless, and the company doesn’t want me anymore,” he said.

Others felt demotivated, a sense of deprivation, and anger at how they had been treated. This harmful impact on mental health and well-being can be exacerbated for those whose level of responsibility decreases alongside their wages. Although the hours and intensity of G. Young Soo’s workload at his insurance company stayed the same under the peak wage system, his decision-making authority was reduced. After 36 years of loyal service, he felt the company mistreated him. Under the peak wage system, he said, “Regardless of your career or your position, you are pulled out from managerial positions such as team leader or director.”

G. Young Soo said he finds the peak wage system particularly unjust because South Korea is shifting away from a seniority wage system to a performance-based one that does not pay older workers more because of their age. “For example, in my company there are younger workers who get a higher salary than me,” he said.

Also, according to the public transport worker C. Eun Jung, 55, the fact that the peak wage system is not applied universally causes a sense of injustice among those who are subjected to it. “Civil servants are not affected by the peak wage system,” she said. “So many people feel it is unfair.”

Financial Harm to Older Workers

The reduction in salary has a significant financial impact. In a 2024 survey of 69 companies in the public and private financial sectors, the Korea Labor and Social Research Institute found that employers reduced wages of those under the peak wage system by an average of 35 percent a year.

In its 2020 report, Korea Labor Institute warned that while the mandatory retirement age of 60 or older may extend an older worker’s tenure at certain companies, the accompanying use of the peak wage system had the potential to force workers into poverty. Government guidelines for public institutions state that the system should not be applied to anyone earning 150 percent or less of the minimum wage, which was KRW3,091,100 or (US$2,316) or less in 2024, at the time of Human Rights Watch’s interviews. However, these guidelines do not apply to private companies. The media has reported cases where earnings fall below the national minimum wage once the peak wage system is applied.

The peak wage system can have a negative knock-on effect on other financial entitlements. G. Young Soo and his employer pay a total of 9 percent of his salary into the National Pension System. “Since my salary is being reduced by the peak wage system,” he said, “then the amount that I [and my employer] contribute to the [National Pension] System will also be reduced and so my total savings will be less and therefore the amount I receive when I am eligible [for my pension] will be less.”

Severance pay, a legally guaranteed payout at resignation or retirement after at least one year of continuous service, can be significantly reduced if it is based on a final, reduced wage, rather than the peak wage before reductions. H. Kyung Ok, 57, said her husband retired at 57 before his company’s peak wage system would have affected him because if he had stayed until 60, his severance pay would have been based on a salary reduced by 50 percent.

Unemployment payments under the Employment Insurance System can also be negatively affected by the peak wage system. Unemployment payments are based on 60 percent of the average usual earnings of the three months prior to being forced to retire, and so reduced wages under the peak wage system leading up to mandatory retirement would also reduce the level of unemployment payments.

“Honorary retirement” is where employers encourage employees to voluntarily retire before the mandatory retirement age. G. Young Soo, said his employer “pressured” workers to resign in 2013 and 2016. The company offered a special bonus to 55-year-old employees to resign instead of working longer under the peak wage system. He said only 18 percent chose to keep working. “We needed a lot of courage to choose to work until the age of 60 under the peak wage system.”

Such “early” retirement resulting from the enforcement of the mandatory retirement age and peak wage system contributes to the low average retirement age from a main job of 54.9 years.

Employers’ Inconsistent Application of the Peak Wage System

Since employers are free to decide the exact rate and duration of salary reductions, discrepancies in how different employers apply the peak wage system disproportionately disadvantage some older workers. G. Young Soo said his employers first reduced his salary by 20 percent when he was 56. They further reduced it by 10 percent each year so that at age 60, he would earn only 52 percent of what he earned at age 55. “It is discrimination because our income has been reduced because of our age,” he said. “It is not justified.”

Seoul National University Hospital, by comparison, has a peak wage system of one year, at age 60, when workers can choose to work full-time for 100 percent of their salary or stop working and participate in “merit training”courses to prepare for life in retirement at 60 percent of their salary. Hyun Jung Hui, who works at the hospital branch of the Korean Health and Medical Workers Union, said the union was instrumental in securing the extent of the wage reduction and its duration at the aforementioned hospital. “If the union had said nothing, we would still only receive 80 percent [of our salary] at the age of 59 and 70 percent at the age of 60,” she said.

Older workers in lower-level positions, already on lower pay, may also be disproportionately affected. The public corporation where C. Sung Ho, 57, works has six staff levels. Those in the lowest three levels receive a 25 percent salary reduction at ages 58 and 59, whereas those in the top three levels have a 25 percent reduction only at age 59.

Compensation Does Not Remedy Reduced Wages

Some employers offer programs or opportunities as compensation for the reduction in salary. These vary from one employer to another and can include reduced working hours, extra vacation days, training opportunities, or being paid to train other staff.

However, in an April 2024 survey of 69 companies in the public and private financial sectors by the Korea Labor and Social Research Institute, 44 percent said the working conditions of those under the peak wage system remained the same, despite their wage reductions.

Even when compensation is provided, some of those interviewed for this report do not regard it as a good substitute for the loss of wages. Kim Dai Hun, 63, who was forced to retire at 60 and whose salary was reduced by 14 percent in the first year of the peak wage system and 28 percent in the second, told Human Rights Watch that he got two extra vacation days per month under the peak wage system and could train staff for five hours a month for KRW200,000 ($139). He said: “Yes, I took the vacation days, and I did the training, but because I believe the loss was way bigger than the reimbursement, I felt a strong sense of deprivation.”

Is Unnecessary

One of the peak wage system’s aims was to encourage youth employment. However, there are other options for increasing youth employment that do not cause such mental and financial harm to older workers for South Korean authorities to explore. Retaining the peak wage system is not a necessary component of these policies.

The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), a standard-setting intergovernmental organization of 38 members, cites several reasons for South Korea’s high youth unemployment, including the impact of the Covid-19 pandemic, a mismatch between high levels of tertiary educational attainment and available jobs, and a decline in vocational education.

The Ministry of Employment and Labor has a number of policies to support young people in their job search and starting businesses, and employers in hiring them. They include the National Employment Support System, which provides an allowance, career counselling, and vocational training opportunities to groups struggling with low employment rates, prioritizing those age 15 to 34, among others. In 2024, the labor ministry piloted two youth employment programs, the “Youth Employment Leap Incentive Program,” which subsidizes employers who employ younger workers, and the “Regional Youth Employment Networking Program,” which supports younger people in their job search. The ministry also funds the University Job Plus Center Project, which runs over 120 career centers in universities, supporting students and local young people to find jobs. Human Rights Watch wrote to the Ministry of Employment and Labor in March 2025 to ask for information it had on the impact of other policies or programs aimed at increasing youth employment since 2016. The ministry responded in March 2025 stating it did not have this information.

Many companies have indicated they do not find the peak wage system helpful. In a 2021 survey of 1,021 companies by Korean Enterprises Federation, of the 594 that said that retaining older workers beyond the age of 60 under the mandatory retirement age was a burden, only one-third felt that the peak wage system was a suitable measure to relieve that burden. Others suggested alternatives including reforming the wage system and skills training for older workers.

The government tries to create more jobs for older people, but they switch from regular jobs to contract [non-regular] ones that are outsourced to private companies.

—Park Hae Chul, 58, railway engineer, Seoul, August 30, 2024