Warsh argues that ‘inflation is not inevitable; it is, in fact, a choice made by central banks,’ rather than being caused by external factors. He criticizes the Federal Reserve for deviating from its mission of price stability, engaging in excessive quantitative easing during non-crisis periods, which has fueled fiscal irresponsibility and undermined its own independence. Warsh calls for the Fed to undertake a ‘reform, not revolution,’ returning to its core responsibilities, while the Treasury should assume its financial obligations.

‘Inflation is not inevitable; it is, in fact, a choice made by central banks.’ This is the central argument of Kevin Warsh in a recent podcast. As a former Federal Reserve governor during the 2008 financial crisis and a strong contender for the next Fed chair, his views carry significant weight.

In the podcast, Warsh emphasized that true inflation stems from monetary policy and is the responsibility of the Federal Reserve. Central banks have the full capability to control inflation levels, but the Fed has strayed from its core mission of maintaining price stability. He reiterated that the measure of the Fed’s competence is whether inflation is low enough to be unnoticeable, and the current situation clearly falls short of this standard.

Warsh also delved into the dangers of inflation, the lingering effects of quantitative easing, and the growing entanglement between the Fed and fiscal policy. He argued that the Fed’s large-scale bond purchases during non-crisis periods have encouraged fiscal irresponsibility in Congress and the presidency. He called for a thorough post-mortem of the severe inflation. Warsh also stressed that the Fed’s independence is being eroded, which not only weakens its ability to address economic challenges but also sows the seeds for sustained inflation.

Warsh also delved into the dangers of inflation, the lingering effects of quantitative easing, and the growing entanglement between the Fed and fiscal policy. He argued that the Fed’s large-scale bond purchases during non-crisis periods have encouraged fiscal irresponsibility in Congress and the presidency. He called for a thorough post-mortem of the severe inflation. Warsh also stressed that the Fed’s independence is being eroded, which not only weakens its ability to address economic challenges but also sows the seeds for sustained inflation.

Drawing on the wisdom of economic giants such as Milton Friedman, Paul Volcker, and Alan Greenspan, Warsh issued a stern warning against institutional complacency. He called for the Fed to undertake a ‘reform, not revolution,’ to refocus on its most fundamental duties. He emphasized that the Fed’s position is crucial and that it has the capacity for self-reform, but it must confront and resolve thorny strategic issues rather than evade them.

Despite the many challenges, Warsh remains optimistic about the future of the U.S. economy, believing that the country is on the brink of an unprecedented ‘productivity boom’ driven by innovation, productivity, and the enduring vitality of the American people.

The following are highlights from the interview:

I believe in Milton Friedman’s view, and I agree with you that inflation is a choice.

I believe that some people in our industry think this is easy and that everything is under control because we have become very proficient at this work. We may all be a bit complacent about this job, but adhering to the basic principles is not so straightforward. I suspect that it is due to the recent crises in 2008 and 2020 that we have lost focus on the essentials.

I believe that money and monetary policy are related, but it has not been included in the discussion. I think this is partly why the current inflation has resurged.

Printing trillions here and there will eventually come at a cost.

Many of my colleagues and I supported it (QE1) based on a consensus: before the next crisis, these dangerous tools should be put back in the toolbox. However, we never truly did that… From that moment to now, central banks have been in the news headlines.

It is important that we return institutions like the Federal Reserve to their former state—organizations that, most of the time, remain on the sidelines and only intervene in specific circumstances.

If you treat every day as a crisis for more than a decade, when a real crisis comes, you have to break more rules and get involved in more unconventional activities. The consequence is that the status of what should be the world’s premier and most important institution (the Federal Reserve) is eroded.

This is a historic and dangerous issue. It shifts the responsibilities and accountability that should belong to fiscal policy to the central bank.

If our annual growth rate can exceed the Congressional Budget Office’s (and most forecasting institutions’) predictions by 1 percentage point, it would bring an additional $4.5 trillion in revenue to the federal government. This is a good way to address these liabilities, so it is not too late yet.

I believe the current government inherited a fiscal and monetary mess, and it is the government’s responsibility to get out of this mess.

We hope that the Treasury and the Federal Reserve can reach some sort of agreement, as they did in 1951. Who should be responsible for what? Who manages interest rates? The Federal Reserve. Who handles the financial accounts? The Treasury.

This country is on the brink of a productivity boom. In my view, the impending productivity boom will overshadow even the 1980s.

The Federal Reserve does not need a revolution; it has already undergone a transformation over the past decade. What is needed now is a degree of repair.

When the central bank resolves the inflation issue and achieves price stability once again, the rest of the world may still not like us, but they will look at the United States and conclude that, despite all the criticism, their economy is growing faster, and that is where we should invest.

I believe that this (regulatory) tax is being phased out… The ability of people, especially Americans, to adapt to new technologies and thrive is underestimated, and this ability is very real.

The full transcript of the interview is as follows:

Wash: Self-reform of the Federal Reserve is crucial for its future.

Peter Robinson:

For over a century, the Federal Reserve System has been tasked with maintaining price stability and combating inflation. How has the Fed performed? Our guest today believes that its performance has been less than satisfactory. Kevin Warsh joins us on Uncommon Knowledge.

Welcome to Uncommon Knowledge, I’m Peter Robinson. Kevin Warsh is from upstate New York, and he earned his undergraduate degree from Stanford University and his law degree from Harvard University. Mr. Warsh’s early career was spent on Wall Street and in Washington. In 2006, President George W. Bush appointed him to the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve, where he served until 2011. Notably, Mr. Warsh served as a Fed official during the 2008 financial crisis, the most severe since the Great Depression. Currently, Mr. Warsh works at an investment firm in New York and is a distinguished visiting fellow at the Hoover Institution at Stanford University.

Kevin Warsh:

It’s great to be back. You omitted the most important part, which is the investment firm I work for and the greatest investor in the history of the world, Stan Druckenmiller. But you kept it under wraps, and I appreciate that. I just wanted to take the opportunity to praise my friend.

Peter Robinson:

Partly because I hope he will eventually join our show, so let’s start by buttering him up. Kevin, the first question. The Federal Reserve was established over a century ago as the domestic institution responsible for maintaining the value of the dollar. Quoting the late legendary investor Charlie Munger: ‘Destroy the currency, and who knows what may happen.’

The second quote is from your speech to the Group of Thirty, a bankers’ organization, in April this year. I’ve excerpted your description of the current Fed: ‘an institution that has strayed from, failed to fulfill its statutory mission, fueled a surge in federal spending, seen its role overly expanded, and performed poorly.’ Kevin Warsh, you are attacking a hallowed institution, one that each of us relies on every day, one that affects the credibility of the money we earn and spend. What exactly are you doing?

Kevin Warsh:

In the world of central banking, we are taught to keep our criticisms to ourselves, Peter. So, in that speech, I clearly did not do a very good job. Peter, I felt it was more like a love letter than a cold critique. You may not have seen it as a love letter, and I’m not sure if the current Fed officials see it that way either.

Peter Robinson:

Let’s not dwell on this ‘love letter’.

Kevin Warsh:

I called it a love letter because the institution is so important. If the Federal Reserve can reform itself, it has a tremendous opportunity ahead. But it does mean that it’s time to get back on track.

This is the third experiment with a central bank in the United States. It’s the third not because the previous two went well, but because they both failed. This is not like winning a third Super Bowl, Peter; more is not better. The first two failed because they lost public support and the ability to deliver on their promises.

We are not in a history class, but let’s recall the Andrew Jackson era when the central bank seemed to serve only the special interests of the East Coast and ignored the interests of the American heartland.

My concern is that this situation is repeating itself today. This central bank has existed for over a hundred years, and if it can reform itself, it will have another glorious century. If it cannot, I will be deeply concerned.

Peter Robinson:

I will get back to you on that, but first, please help me understand. I am an amateur in these matters, while you are an experienced central banker and investor who understands this field, which I do not. So, please guide me through this. I have some very basic questions, so allow me to set the stage.

The Federal Reserve System was established in 1913 with the power to set interest rates and regulate the money supply, aiming for price stability. These are significant powers. How has it performed?

Here is a quote from Milton Friedman, the 1976 Nobel laureate in economics: ‘No institution in the United States commands such high public esteem and yet has such a poor record of performance. The Federal Reserve began operations in 1914. Under its leadership, prices doubled during World War I and then led to a severe economic collapse in 1921. The primary culprit of the Great Depression was undoubtedly the Federal Reserve System. Since World War II, it has overseen another doubling of prices and financed the inflation of the 1970s. The harm done by the Federal Reserve far outweighs any benefits, and I have long advocated for its overhaul.’ Kevin, why do we need the Federal Reserve System? None of this is new to you. You were an undergraduate at Stanford when Milton Friedman was there.

Kevin Warsh:

Milton, I had the privilege of being his student. During his time at Stanford, he had a tremendous impact, not only on me but also on generations of students that followed. I spent a considerable amount of time in the Hoover Institution archives, looking up Milton’s views. For example, our colleague Jennifer Burns wrote an excellent book that includes some of his letters. I had them pull out all the correspondence between Paul Volcker, Milton Friedman, and Alan Greenspan.

Peter Robinson:

Alright, please tell us about the time context. Paul Volcker was appointed as the Chairman of the Federal Reserve by Jimmy Carter in the 1970s, specifically in 1979.

Kevin Warsh:

It was during the middle of the Carter administration; I don’t have the exact date.

Peter Robinson:

He was then reappointed by Ronald Reagan and served until near the end of the Reagan administration. Alan Greenspan succeeded him and served until…

Kevin Warsh:

He served for 17 years, until Ben Bernanke took over. I remember this period because I was a staff member at the White House at the time. I recall that Chairman Bernanke was about to leave the White House to take over from Alan Greenspan, and he hoped that I would join him to take up the position of a Fed governor that he had previously held.

And Milton, in his correspondence, one of the remarkable things is that he constantly re-examined his preconceptions. He would continually reflect on whether the data and conclusions he drew in the previous year, and his judgments on institutions, still held true the next year. In most of the correspondence during the Greenspan era, he was quite pleased with the changes in approach, the new ways of thinking about the economy, and what later came to be known as ‘the Great Moderation.’ So, I wouldn’t say that Milton thought the Fed was a bad institution; he just believed its performance was sometimes good and sometimes not so good. I can only speculate how he would have evaluated the last six years of high inflation; he likely would have foreseen it and issued a warning—something the Fed failed to do.

Warsh: Inflation is a choice made by the Federal Reserve, not an excuse for external factors.

Peter Robinson:

Let me ask a basic question. Milton Friedman famously said, ‘Inflation is always and everywhere a monetary phenomenon.’ If inflation is a monetary phenomenon and the Federal Reserve is responsible for the money supply, then inflation, ultimately, is always the Federal Reserve’s fault. Tell us what Paul Volcker did when he was appointed by President Carter. At that time, we were experiencing the worst inflation since the Civil War. By the time Paul Volcker left office, inflation had fallen to around 2%. So, Milton Friedman was right: the Federal Reserve is always responsible.

Kevin Warsh:

I believe in Milton Friedman’s view, and I agree with you that inflation is a choice. When Congress reviewed its statutes in the 1970s, it assigned the responsibility of controlling inflation and ensuring price stability to the Federal Reserve, creating an institution dedicated to addressing price issues. The message from Congress was, ‘Stop blaming others. We are handing the baton to you, the central bank, to get this done.’

But from the past few years, you might not think that inflation is a choice. During the high inflation period over the last five or six years, what have we heard about the causes of inflation? It was Putin’s actions in Ukraine, the pandemic, and supply chain issues. Milton would have been very upset if he heard this, and I find these explanations troubling.

These external factors can cause individual prices to change—Walmart’s prices change every day in a market economy, and that’s how a market economy works. Regulating these specific prices is not the central bank’s job, and it is not the essence of inflation. That is just a one-time change in the price level of a particular good. Only when this one-time price change becomes self-fulfilling, meaning that rising prices lead to further price increases, does it become inflation. This means that inflation eventually permeates every household and every business because, as a decision-maker, you cannot predict future price levels.

This has nothing to do with Putin’s actions or the pandemic; it has everything to do with the Federal Reserve, with the central bank. I am concerned that in recent years, the central bank may have been influenced by the ‘It’s not my fault, it’s someone else’s fault’ mentality that pervades our culture. I think this is exactly what would most infuriate Milton in the current era. The central bank can achieve any inflation level it wants. We may not like its methods, but the idea that the central bank should blame others, in my view, is completely at odds with fundamental economic principles.

Peter Robinson:

I would like to reiterate a point that may be crucial for our upcoming discussion: not only is inflation a choice, but a stable dollar is also a choice. We have experienced severe inflation, but the Federal Reserve has successfully brought it under control. All of this has happened within living memory. Let’s move on to another basic question.

Kevin Warsh:

The Federal Reserve did regain control, but I suspect that this might sound like jargon to those outside the field. Subsequently, during what we call the ‘Great Moderation’—a period of over a generation where prices remained relatively stable—they seemed to become complacent about controlling inflation. Some in our industry felt that it was easy and well-managed because we had become very proficient at it. We might have all become a bit complacent about this task, but adhering to the fundamentals is not so simple. I suspect that the recent crises in 2008 and 2020 may have led us to overlook the key points.

Peter Robinson:

You have used the term ‘Great Moderation’ several times. Let’s define it. The ‘Great Moderation’ period, as I understand it, began in the mid-1980s when the Federal Reserve under Paul Volcker and the Reagan administration managed to bring inflation down to single-digit levels. Since then, inflation has remained low, and the economy experienced sustained growth for the next 25 years, with only a few quarters of recession until the 2008 crisis. Is that what you mean by the ‘Great Moderation’?

Kevin Warsh:

Exactly. Of course, it’s not to say that every year was perfect and that central bankers never made any mistakes, but those mistakes were relatively small and manageable. For the general public, inflation can be a very abstract concept. We aim for price stability to the extent that no one in the economy talks about it. That’s how we gauge whether we’ve done our job. And in the last five to six years, how has it been? Inflation has been a topic of conversation for almost everyone.

“The world has moved forward, and we must deal with the present situation.”

Peter Robinson:

This is my final basic question: gold. President Nixon took the United States off the Gold Standard in 1971. Prior to that, the US dollar was convertible into a fixed weight of precious metal (primarily gold), which constrained the money supply.

Journalist and investor James Grant wrote last year that the opposite of the Gold Standard, which is the system we have now, might be called the ‘PhD standard,’ where domestic experts adjust interest rates at their discretion. Therefore, James Grant suggested that if not the Gold Standard, then some fixed basket of commodities should be used.

Milton Friedman, around the same time, long advocated for the abolition of the Federal Reserve, arguing that it should be replaced by an annually announced, fixed-amount increase in the money supply. This way, the market would be completely transparent, allowing for planning ten years in advance. Both views are seeking an objective standard, a way to limit the money supply that the market can foresee, rather than leaving everything to subjective impulses, groupthink, and the experts within the Federal Reserve System. Now, Kevin Warsh responds.

Kevin Warsh:

There is no state of ‘return’ to go back to, although many of my friends on the right believe in a straightforward return to the Gold Standard. The world has moved forward. We must deal with the present situation. As Orwell said, there must be a third option between ‘letting the machine do it’ and ‘leaving it entirely to the latest whims of the central bankers.’

I think both you and I may have learned something from the conservative Edmund Burke. At the heart of conservatism is the resistance to caprice. Anchors to the past and present are needed to resist such whims. We need a way to clearly understand how central banks react to new information. If Milton were with us today, I wouldn’t presume to speak for the great man, but I think he would say that there is too much scientism and scholasticism trying to precisely define things we still don’t fully understand.

Most of us are better than average in economics, and we try to focus on the left side of the decimal point rather than the right. If we were more outstanding and smarter in our field, we would become physicists and mathematicians. Most of us in this industry started in one of these fields before moving into economics, frankly, because it is easier. Therefore, we do not yet have a perfect understanding of how the economy works. If we did, we could create machines and formulas. However, the economy changes every day; it is highly dynamic. So, I am not too confident that we have a perfect set of rules.

Warsh Recalls the 2008 Crisis: Federal Reserve Intervention, Lack of Monetary Understanding, and Unfulfilled Promises

Peter Robinson:

Now let’s turn to recent history—specifically, the financial crisis you and the Federal Reserve experienced and its aftermath. During the 2008 financial crisis, you served as a member of the Federal Reserve Board, which led to the most severe economic contraction since the Great Depression and an increase in domestic unemployment.

Kevin Warsh:

The unemployment rate reached 10%. Peter, are you suggesting there was a causal relationship? I don’t think so.

Peter Robinson:

I’m a bit apprehensive about how to start this. You really had bad luck. The Federal Reserve took a series of actions, the most notable of which was perhaps the massive injection of liquidity into the financial system. Let me give you an idea of the scale of the Federal Reserve’s actions between the first and second quarters of 2008: the Federal Reserve’s balance sheet, which measures the supply of reserves in the banking system, doubled from $1 trillion to $2 trillion in just one quarter. You wrote that you strongly supported that decision. So, before we discuss QE2, QE3, and QE4, which made you very uneasy, please tell me why you supported the massive infusion of funds into the market in 2008?

Kevin Warsh:

First, let’s talk about the word ‘money,’ which we have been mentioning frequently. As you pointed out, Milton Friedman believed that monetary policy and inflation are related to money. This is a heretical view in modern academia and is not taught in most introductory economics courses at elite universities. Most scholars come from different schools of thought, not the monetarist school, but rather the Keynesian school. In Keynesian theory, money is rarely mentioned. In fact, if you look at the minutes of the Federal Reserve, which record much of what is said within the Federal Open Market Committee, you will find that the word ‘money’ is almost non-existent.

Strangely enough, I believe that money is related to monetary policy, but it has not been included in the discussion. I think this is part of the reason for the resurgence of high inflation. I don’t think Friedman himself would fully adhere to the model he had in mind 30 years ago, but he might say that it is related to money. During the period leading up to and following the COVID-19 crisis, when high inflation was brewing, we saw a surge in both the quantity and velocity of money.

In most discussions of modern economics, it is absent. Now, I want to quote Milton Friedman one last time before we move on to current events. When I was 19 or 20 years old, I sat around a table with Mr. Friedman, and there were a few more people than there are now. I asked him some questions, perhaps trying to show off and pretend to know something I didn’t. He said, ‘Kevin, in the field of economics, the only thing we truly understand is what is taught in introductory economics courses; everything else is made up.’ I remember thinking, ‘Peter, maybe this old man is confused, after all, he won the Nobel Prize a long time ago.’ It wasn’t until the financial crisis you just mentioned that I realized how right that old man was. No one predicted the crisis, no one noticed the risks, because the economics we truly understood came from the introductory course, at least before the mainstream schools dominated these elite departments, and we believed that money and monetary policy were related. I still believe this to be true.

Peter Robinson:

By the way, it has been nearly 20 years since the financial crisis. Can you take a moment to explain what happened back then? For example, how would you describe the severity of the situation to your friends in New York when you were a Federal Reserve governor in Washington? What do we need to understand?

Kevin Warsh:

That crisis? I occasionally teach at a business school not far from where we are recording. Over the years, I have talked about the global financial crisis. The students today still have some recollection of the crisis, even though they were not involved in business at the time, but they remember how their parents came home or what they saw on TV. Now, when I talk about the global financial crisis, it feels to them like I am talking about the Great Depression, something that happened a long time ago.

At the time, I felt that at 35 years old, I had reached this prestigious position because of President Bush and Ben Bernanke. I worked in that beautiful office for about six to eight months, and everything was very pleasant. Someone would come in to add wood to the fireplace, and others would bring me a fresh pitcher of iced water. I thought everything was wonderful.

I had no idea that it was the calm before the storm. In hindsight, the situation was more terrifying than we actually felt, as we were, in a sense, all together in the ‘bunker.’

I wonder if Ben Bernanke would be comfortable with what I said a few weeks ago at the IMF G30 meeting? He was an outstanding commander in the battle. We were all in the ‘bunker,’ and he was very willing to sit around a table with a small group of people, discussing what was happening and why, and he was quite open to unorthodox ideas. I wonder if such unorthodox thinking is still allowed in the profession or in central banks today.

But on the darkest days of that crisis, our performance in handling it might only deserve a B grade. We could have done more earlier, and we made many mistakes, but we also had some successes. The real economy deteriorated faster than at any other time in history. Stock prices in financial markets fell by 60%-70%, and perhaps most concerning was the situation in the Treasury bond auctions. As the most important securities in the world, closely tied to the credibility of the U.S. dollar, there were very few participants in these auctions. The bid-ask spreads were enormous, and we were worried that the U.S. financial system was in a very dangerous place.

Peter Robinson:

On the brink. So, in my memory, injecting liquidity into the system was an emergency measure aimed at maintaining the normal functioning of the markets. The theory was that keeping the markets open and functioning, providing enough money for transactions, was the most direct and effective action at the time. The market itself would gradually solve the problems. Was that the only reason?

Kevin Warsh:

It goes back to first principles. The third experiment of the central bank, which is the system we are in now, was created in 1913, precisely to address the kind of financial panic that occurred less than a decade before its founding. During those deep recessions, financial crises meant market failure, with a large gap between the price buyers were willing to pay and the price sellers were willing to accept. The role of the central bank was to come in with funds (that unpopular word again) to get the market working again. The central bank’s job is not to set prices, but to ensure that buyers and sellers can transact, and to step in when no one else is willing to provide liquidity.

We have been, and continue to be, the last line of defense for the banking system, not just in the United States, but in other parts of the world as well. If we fail, the situation in other regions will be even worse. This is what we did during the crisis. Some of our friends on the right, including those in certain institutions, whose opinions we care about, believe that the system should be allowed to collapse, believing that a phoenix will rise from the ashes.

That is not my view. My view is that central banks are established to deal with panics, and we were facing a panic. Although we were late in recognizing it, we then intervened with overwhelming force. The term ’emergency’ you used is very appropriate. In such situations, you are prepared to cross more boundaries than you would in normal times. As Paul Volcker famously said, in a sense, you must be ready to use all the power at your disposal. But we had an implicit commitment, not just internally, but also to the Treasury, to Congress, and to the entire U.S. government.

This commitment was that, once the crisis was over, we would step back and become a rather dull central bank, appearing only on page 12 of the newspaper, in six small paragraphs, reporting that ‘the Fed met today and decided to raise or lower interest rates by 0.25 percentage points.’ However, since that time, central banks have been front-page news. I think their role has expanded beyond what the founders of central banks would have found acceptable.

The Costs of QE2, QE3, and the Broken ‘Agreement’

Peter Robinson:

Let’s go through this from 2008 to the present. I might get some details wrong, so please correct me. A quick rundown: QE1, or quantitative easing, which was a way of injecting funds into the system, was implemented in 2008, and we’ve just discussed it. The Federal Reserve’s balance sheet grew from less than $1 trillion to over $2 trillion, and Kevin supported this. QE2 was implemented in 2010, and the Fed’s balance sheet rose to nearly $3 trillion. QE3 was implemented in 2012, and the Fed’s balance sheet expanded to $4 trillion. QE4 occurred during the 2020 pandemic lockdown, another emergency, and the balance sheet peaked at $9 trillion. Since then, the Fed has reduced it to $7 trillion. As you pointed out, the Fed’s balance sheet is now almost an order of magnitude larger than when you joined in 2006. We’ve already discussed QE1, so let’s talk about QE2 and QE3, the pre-pandemic expansions in money supply.

Kevin Warsh:

Printing trillions here and there, Peter, comes at a cost. In the old Washington, if a government agency spent millions on one project or billions on another, we could tolerate that, even if the projects were not perfect. But when the Fed prints trillions, especially during good economic times, everything changes. It’s almost like sending a signal to Congress: if we can do it, so can you. Let’s get back to the essence of quantitative easing. By the way, QE1, when we were trying to promote it, was called ‘credit easing,’ but that term lasted only about a week before ‘quantitative easing’ (QE) became popular without us.

We had internal discussions about whether to proceed. The story goes something like this: Peter, then-Treasury Secretary Paulson, was going to issue Bonds on Monday and Tuesday. What do you think about us buying them on Thursday and Friday? I won’t name who said it, as I don’t want to betray the trust of my colleagues, but I remember someone saying, ‘This sounds like a Ponzi scheme.’ Someone explained that the Bank of Japan had implemented a similar, albeit smaller-scale, measure about a decade earlier, but nothing on this scale had ever been attempted. We were not entirely sure how it would work, but it turned out to be successful. At the time, it was very radical. Now, if you open any mainstream economics textbook, even an introductory one, it will describe this as a standard operating procedure.

It seemed like a gamble at the time, but we were in a situation where a gamble was necessary, so we went ahead with it. That was QE1. Many of my colleagues and I supported it based on a shared understanding that these dangerous tools should be put back in the toolbox before the next crisis. However, we never really did that. Subsequent rounds of quantitative easing occurred during what I believed to be a period of strong growth, stable financial markets, and price stability. We began using this tool under any circumstances, for any reason. By doing so, we also raised the bar for responding to the next crisis, because whatever we had done before might not be enough. I should point out, though, that you are embellishing my resume, which I appreciate, but I resigned after QE2 was launched in 2010. You mentioned this.

I left in early 2011. My colleagues, including Chairman Bernanke, whom I greatly respect as a ‘warrior’ and his colleagues at the Federal Reserve, decided to continue with quantitative easing.

Peter Robinson:

On what grounds? If you could present the strongest argument for their decision, what would it be?

Kevin Warsh:

The reasoning was that we didn’t see any costs; it seemed like a free lunch. Looking around, asset prices were higher, market liquidity was more abundant, and the economy was in good shape. Goodness, if we stopped, who knows what might happen. In my view, they broke the agreement we had. Who among us truly knows what would happen in various scenarios? No one does. Unlike physics, we don’t have a true control group in economic research. Another difference between economics and physics or mathematics is that the ‘atoms’ we track—people—can change their minds. So, we don’t know how individuals will react to a series of policies. But the argument at the time was that since the costs were low and the benefits were high, let’s keep going.

During the pandemic, the Federal Reserve’s excessive intervention and fiscal abuse sowed the seeds of future problems.

Peter Robinson:

The fourth round of quantitative easing (QE4) occurred during the COVID-19 pandemic. In 2021, Paul Schmelzing wrote: ‘In a situation where the government is suppressing economic activity to contain the pandemic, fiscal policy needs to play an important social insurance role by providing income support to households and small businesses. Moreover, the more monetary policymakers demonstrate their commitment to achieving inflation targets by implementing aggressive QE policies and injecting more liquidity into the system, the more credible they will be in addressing inflation.’

Kevin Warsh:

There is a lot to unpack in that statement.

Peter Robinson:

Please elaborate.

Kevin Warsh:

During crises like 2008 or the pandemic, we indeed need to take aggressive measures. I also thought this way as an observer at Stanford and New York during the 2020 pandemic. The problem lies in the periods between these crises. For most of the decade from 2010 to 2020, we were not in an emergency, which should have been the time for the central bank to step back. However, the central bank continued to make headlines. I should also point out that, during that relatively peaceful and prosperous period, the logic in Congress was: if the central bank buys all the Bonds, then we can spend trillions of dollars. Therefore, the fiscal authorities, Congress, and the president concluded that the cost of all this spending was extremely low because the Federal Reserve subsidized it by becoming the primary buyer of these Bonds.

When you are in a crisis, I sympathize with the colleagues who need to take measures to address it. But if you treat every day as a crisis for over a decade, then when a real crisis hits, you have to break more boundaries and get involved in more extramural activities. The consequence is that you see the erosion of the status of what should be the world’s foremost and most important institution (the Federal Reserve) — not just ‘first among equals’ — being undermined. You see Republican and Democratic administrations, members of Congress, and, more importantly, businesses now hiring lobbyists to go to the central bank for relief.

Peter Robinson:

(They are) unelected bankers.

Kevin Warsh:

This is a historic and dangerous problem. It shifts the responsibilities and accountability of fiscal policy to the central bank. Although my colleagues are well-intentioned and may even make some right calls, many of these things are not within their purview.

Peter Robinson:

Kevin, let me respond on behalf of the Fed. You’re right, but look at where we are today: inflation has fallen below 0.5%, and the economy is still growing. So, people shouldn’t blame the Fed; they should say, ‘Ladies and gentlemen, well done.’

Kevin Warsh:

For policymakers in Washington, declaring ‘mission accomplished’ is extremely dangerous, and what you just said is equivalent to such a declaration. After most crises, Peter, such as 9/11 and the global financial crisis, there are a series of post-mortem reports, congressional reviews, and investigations by ‘blue-ribbon committees.’ However, after this severe inflation, I am still waiting for similar assessments to be conducted.

Instead, we have only partially addressed the issue, and in my view, the institution (the Federal Reserve) remains somewhat inadequate, with inflation still above target levels. The Fed has stated that it is conducting a post-mortem report, reviewing its objectives, and will release it in August of this year. I am curious whether this report will confront the challenges posed by this major error: over the past five to six years, compared to pre-pandemic times, the prices of goods and services have increased by more than 30%, and federal government spending has grown by 63%. I do not recall anyone five years ago considering this to be an efficient, well-functioning government. Therefore, some consequences cannot be ignored. I acknowledge that the situation has improved, but this mistake has come at a cost, and these costs are being borne by the poorest members of our society.

The Federal Reserve’s position is crucial, and it has the capacity for self-reform.

Peter Robinson:

You have already mentioned some of this, but I want to address more explicitly the damage caused by the Fed. Your article was published in The Wall Street Journal, which is quite an achievement, and I congratulate you on that. I have never before seen the paper publish both a column and a front-page editorial on the same day commenting on the same speech. You managed to do that. Compared to having both sides of the story on the op-ed page of The Wall Street Journal, the Nobel Prize is nothing.

Here is what the editorial said: ‘In 2006, the year you joined the Fed, the federal debt as a percentage of GDP was about 34%. Today, it is around 100% and heading towards 124%.’ The editorial also quoted your statement that this was an irresponsible surge in spending, especially after the pandemic. It is difficult to absolve the Fed of responsibility for the nation’s profligacy. The Fed leaders encouraged government spending during economic difficulties but failed to call for fiscal discipline when the economy was growing steadily and employment was full.

Now, I am going to turn my attention to you, Kevin. So far, I have been defending the Fed’s policies. Now, I am going to turn to you and say, as Niall Ferguson pointed out in a recent, striking column, no government in history has maintained its status as a great power when its interest payments on debt exceed its defense spending. My friend, the alarm bells should have been ringing long ago. You have been too lenient in your criticism of the Fed, and that is too much.

Kevin Warsh:

Now you have me defending the Federal Reserve.

Peter Robinson:

The reverse rule. I’ll see how you handle this.

Kevin Warsh:

I believe the Federal Reserve’s position is crucial, and I also believe it has the ability to reform. Self-repair is essential for all institutions. It is not too late yet, but they need to address and answer those major, thorny strategic questions rather than sweeping them under the rug. Congress should be criticized for its reckless and irresponsible spending. This spending has been accepted largely because the Federal Reserve has been buying these Bonds in large quantities. When the Federal Reserve buys Bonds, it sends a message to global investors that the water is warm, come on in, and you should do the same. However, the President and Congress also bear significant responsibility for pushing large-scale expenditures during times of peace and prosperity. But this is extremely dangerous.

Let me emphasize one more point: irresponsibility is a two-way street, manifesting in the connection between fiscal spending (the function of Congress) and monetary issuance (the function of the central bank). When one side is irresponsible, the other often follows suit. We usually do not see the harm caused immediately. As Milton Friedman famously said, policies have long and variable lags, and there is no such thing as a free lunch.

Let me make a broader point. Peter, when the rest of the world sees our most important national Institutions treating normal times as emergencies, they follow suit. For a long time, the rest of the world has had a certain view of the United States: ‘We really don’t like the way they lecture us at G7, G10, or G20 meetings.’ But before the 2008 crisis, they thought, ‘Those Americans may be a bit aggressive, but they do know how to run a banking system’—until we proved otherwise. Then came the COVID-19 crisis, and they thought, ‘Those Americans, they are different from us, but they seem to truly believe in federalism, freedom, and individual initiative’—until we no longer believed in it. Then they thought, ‘That central bank, maybe we were too harsh on it, but it maintained price stability for 40 years.’ That was quite good, but we failed to maintain it. When these Institutions fail on major issues, the rest of the world is watching.

At this very moment, the rest of the world is watching the Federal Reserve. If the central bank can get its house in order and stop making headlines, thereby prompting Congress to be more responsible in its spending, then the United States can once again become that ‘city upon a hill.’

Peter Robinson:

The late economist Herbert Stein used to say, ‘If something cannot go on forever, it will stop.’ I remember he served as the chairman of the Council of Economic Advisers under President Nixon, right? But he never worked at the Federal Reserve, did he?

Kevin Warsh:

Not to my knowledge.

Peter Robinson:

The late economist Herbert Stein once said: if something cannot continue indefinitely, it will eventually stop. The issue is that we have been operating what amounts to a Ponzi scheme. The Treasury issues Bonds, and the Federal Reserve buys them, which is essentially akin to printing money. Yet, the world continues to buy U.S. Treasury Bonds. In other words, why has the global market not imposed constraints on the United States? Clearly, it seems Ben Bernanke was right; there appears to be no cost involved.

Kevin Warsh:

I would rather hold our (U.S.) cards than those of any other country in the world. I believe we are at the beginning of a productivity boom. Endogenous growth in the U.S. is crucial and more effective in reducing debt than any other method. To give a simple data point, according to the latest report from the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) — I should note that I am a member of an expert advisory panel for the CBO, but they do not necessarily follow my advice — they predict that the U.S. will grow at an annual rate of 1.7% or 1.8% over the next decade.

Peter Robinson:

Growth rate over the next decade? They have no idea. I apologize, but I’m not in your group, and they truly have no clue about what the growth will be like over the next 10 years.

Kevin Warsh:

We don’t even know what will happen in the next 10 minutes. Absolutely. So, I agree with you. But whatever our government does, I would still bet on America. We live in a highly productive society. The government may be busy dealing with the aftermath of the past 15 years of quantitative easing (QE), but the vitality and adaptability of the American people are impressive. If we can achieve a growth rate that is 1 percentage point higher than what the Congressional Budget Office (and most forecasting institutions) predict each year, it will bring an additional $4.5 trillion to the federal treasury. This is a good way to address these liabilities, so it’s not too late yet. But going back to your point, if something cannot go on forever, it…

Peter Robinson:

…will eventually stop. So, where are the warning signals in the global markets?

Kevin Warsh:

I think, whether in our own markets or in the global markets, we do not want to find ourselves again in that critical state where the yellow and red lights are flashing. Because I believe, even now, the U.S. economy is still the best and most promising in the world. We can see concerning situations externally, but I don’t think the problems are entirely unsolvable. However, the longer we delay, the closer we get to that critical point. The best way to avoid reaching that critical point is not to get to the point where we can see it.

Warsh: The Fed Should ‘Quietly’ Print Money, with the Treasury Taking Responsibility, to Tackle Inflation and High Interest Rates

Peter Robinson:

According to a document released by the House Budget Committee in March, the Federal Reserve raised interest rates 11 times between March 2022 and July 2023 to mitigate inflationary pressures caused by Biden’s deficit spending spree. As a result, the average effective interest rate on the national debt doubled from 1.7% to 3.4%, and the net interest cost rose from $352 billion to $881 billion. This means we are now paying more in debt interest than we spend on the Pentagon, which is approximately over $800 billion.

Kevin, the Fed’s balance sheet still stands at $7 trillion. How does it reduce its balance sheet? How can it recover funds without raising interest rates? We must navigate this dilemma, which is truly terrible. Current members of the Fed might say, ‘Kevin, don’t you understand? We are doing our best.’ What is your reform agenda? What is an agenda that won’t make things worse?

Kevin Warsh:

Peter, this might upset some of your audience, so I’ll give a heads-up. I believe this administration inherited a fiscal and monetary mess, and the government has a responsibility to clean it up. No one said it would be easy. We didn’t get into this situation overnight, and we won’t get out of it overnight either.

To put the numbers you mentioned into a bit more context: before the pandemic, we were paying about $1 billion in interest per day. Now, we are paying over $3 billion in interest per day. This money is not enhancing military power or helping the poorest among us; it is being wasted.

What do I suggest? As you pointed out, and as we have discussed, there are two monetary policy tools, though I’m not sure if monetary economics professionals believe this. One is setting interest rates, and the other is what we’ve been talking about, which we call QE or the central bank’s balance sheet. If we could make the printing press operate a bit more quietly, we could lower interest rates. What we are currently doing is injecting a lot of money into the system, which is causing inflation to exceed the target. The $7 trillion balance sheet is an order of magnitude larger than when I first joined the Fed.

Meanwhile, there is another monetary policy tool, which is interest rates. They do not work perfectly together and are not perfect substitutes for each other, but both fall under monetary policy. Many people working in central banks claim that the balance sheet has nothing to do with monetary policy. If this was the case during your formative years, then when the situation is reversed, it should also be related to the implementation of monetary policy. I believe we must be honest about these two tools because I believe that developing the real economy is more important for increasing income, promoting fairness, improving efficiency, and driving growth.

Given that the expansion of the balance sheet has led to rising inflation, we hope to reduce it, but this cannot be done overnight. We hope that the Treasury and the Federal Reserve can reach some kind of agreement, much like in 1951. Who is responsible for what? Who manages interest rates? It is the Federal Reserve. Who handles the financial accounts? It is the Treasury. We have blurred the lines regarding who should be responsible. When a new president takes office, his Secretary of the Treasury should take responsibility as the fiscal authority, rather than blurring the lines and pushing responsibilities onto the Federal Reserve, as this only brings politics into the Fed and interferes with its normal operations.

In my judgment, we should reduce the central bank’s balance sheet and have the Federal Reserve exit these markets, unless there is a crisis. By doing so, there will be less inflation. You and I might call this ‘pragmatism.’ I think this is what our scholars might be contemplating. This approach could actually lead to lower interest rates, which is more important for the real economy than the balance sheet.

Wash: The US Economy is Experiencing a ‘Productivity Boom’

Peter Robinson: 48:37 Kevin, I would like to ask you about two visions for this country. Let me introduce this topic with a few quotes.

Let’s first look back at the past 40 years: This began with the ‘Great Moderation,’ starting from the mid-1980s, where for about 40 years, Americans hardly considered changes in price levels. Everything was proceeding smoothly. We took it for granted because there were smart and hardworking people maintaining the country’s operations.

Peter Robinson:

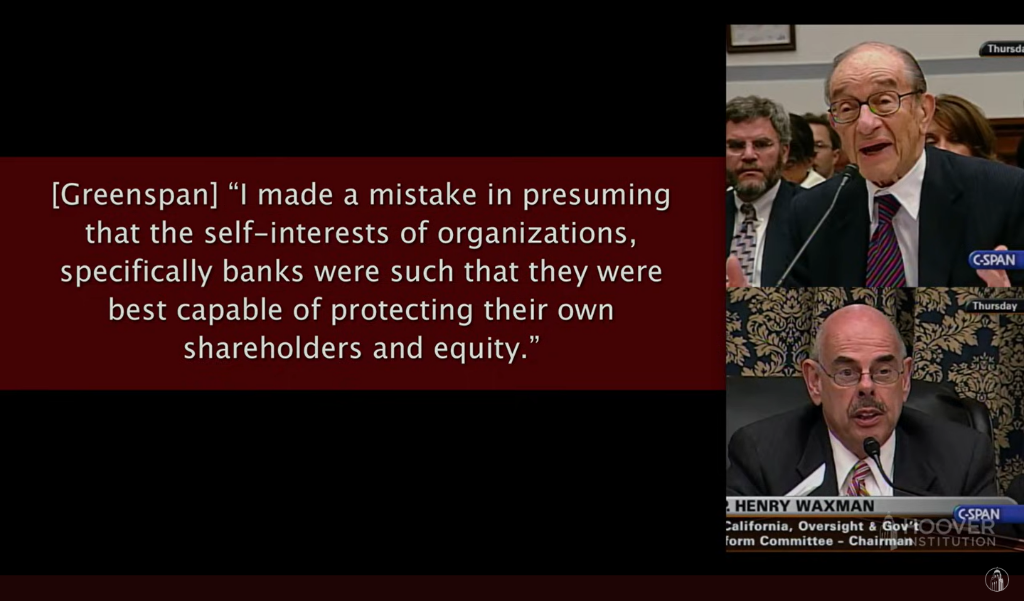

Now, let’s consider the scene where former Federal Reserve Chairman Alan Greenspan testified before Congressman Henry Waxman regarding the 2008 financial crisis.

Greenspan: ‘I made a mistake in presuming that the self-interest of organizations, specifically Banks, would be such that they were best capable of protecting their shareholders and equity.’

Peter Robinson:

These words come from Alan Greenspan, whose career began as a follower of Ayn Rand and who was a staunch believer in free markets. In 20th or 21st century America, you would be hard-pressed to find someone more committed to this ideology.

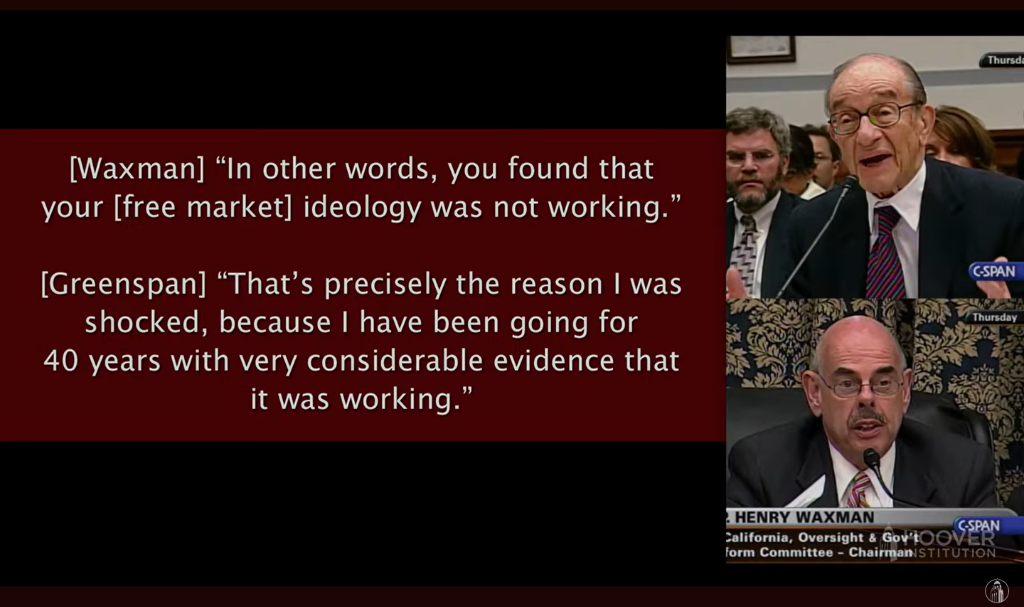

Waxman: ‘In other words, you found that your free-market ideology does not work?’

Greenspan: ‘That is precisely why I am shocked, because for 40 years, I had considerable evidence that it did work.’

Peter Robinson:

There is a view here: going back to the 1980s, starting with Federal Reserve Chairman Paul Volcker and President Reagan, we achieved low inflation and a strong dollar. Overall federal spending was low enough to allow the economy to grow. In fact, the economy grew faster than federal spending. At the beginning of George W. Bush’s term, before the new wars, we actually expected surpluses in the coming years.

But that era is now over. The financial crisis has changed the world. We have experienced more than a decade of fiscal irresponsibility, market distortions, and loose monetary policy, which was further exacerbated by the COVID-19 lockdowns. Now, market professionals like James Grant and Ray Dalio are beginning to question the entire monetary system. Young entrepreneurs are buying Bitcoin because they no longer trust the dollar.

Kevin, is it true that some fundamental things have come to an end and are beyond repair? What do you think of this pessimistic view?

Kevin Warsh:

That is far-fetched. I am not one to give up easily, and neither is this country.

This country is on the brink of a productivity boom. In my view, the upcoming productivity boom will outshine even the 1980s, which you witnessed as a special assistant in the Oval Office.

Peter Robinson:

Is it more than just artificial intelligence? Tell me about your vision. If we stop messing things up, what does the future look like?

Kevin Warsh:

Over the past 15 years, the government has done everything in its power to create obstacles and hinder progress. Despite its efforts to undermine the United States and its role in the world, these attempts have failed.

The 21st century will be America’s century. Public policy need not be perfect. We can conceptualize ideal trade, regulatory, or tax policies with our colleagues, but perfection is not necessary. We only need to make the policies slightly better than they are now, and adjust monetary and fiscal policies in a reasonable direction, and the American economy will flourish.

There is a tendency among some of our peers to advocate for a return to Reaganomics, but those days are over. Hayek once said that our task is to draw on the ideas of the past and rearticulate them in the minds of a new generation.

Therefore, this is not about returning to Reaganism, but about implementing a new set of indigenous policies in the new world that can inspire the American spirit and promote individual freedom and liberation. Importantly, we need to restore Institutions like the Federal Reserve to what they once were—entities that, most of the time, stand on the sidelines and only intervene under specific circumstances. This way, we will have stronger fiscal responsibility and higher endogenous growth. I believe that the new generation of technologies starting here will make the United States a significant beneficiary. This is not preordained, nor is it a birthright, but I believe it is not only possible but highly likely to happen.

The Federal Reserve needs ‘fixing,’ not a revolution.

Peter Robinson:

Two final, summarizing questions. The Federal Reserve does not need to be completely overhauled or dismantled and rebuilt; it just needs to adjust its current course by a few degrees. An aircraft carrier takes some time to turn, but a few degrees of adjustment can solve the problem. Am I right?

Kevin Warsh:

I think you are right. The Federal Reserve does not need a revolution; it has already undergone a transformation over the past decade. What is needed now is a degree of fixing. I know you are not a golfer, but I learned a lesson from a famous golf course designer named Gil Hanse. When he looks at golf courses and thinks about how to restore their glory, he says to draw inspiration from their past but not be bound by it. Be true to the original intentions of the course designer (in this case, the central bank), but do not reproduce it word for word.

Kevin Warsh:

It’s like we can’t return to the regulatory model, monetary policy, fiscal or tax policies of the Reagan era. We can’t go back to the monetary policy of the Reagan era, but we can look back at an institution and strive to restore its best elements, while keeping in mind the changes happening in the world. You mentioned Bitcoin, and I sense a hint of condescension in your tone, as if you are looking down on those who buy Bitcoin.

Peter Robinson:

However, Charlie Munger criticized Bitcoin in the last two or three years before his death, didn’t he? He called it an evil act, partly because it could undermine the Federal Reserve’s ability to manage the economy.

Kevin Warsh:

Or, it could provide market discipline, indicating to the world that some things need to be fixed.

Peter Robinson:

Does Bitcoin not make you nervous?

Kevin Warsh:

Bitcoin does not make me nervous. I can recall having dinner here in 2011 with a guest, who was also another guest on your show. I won’t name him… I just did. Marc Andreessen showed me that initial white paper. I wish I had understood as clearly as he did at the time how transformative this new technology, Bitcoin, would be.

Bitcoin does not bother me. I think it is an important asset that can provide a reference for policymakers when they do things right or wrong. It is not a substitute for the dollar, but I believe it can often serve as an excellent overseer of policy. If I were to generalize, what might Charlie Munger and others be thinking? There is a proliferation of securities under various names, many (if not most) of which are not valued in line with their trading prices.

So, what did Charlie say, and perhaps what did his good friend Warren say? There are innovators, imitators, and incompetents. Within and around this new technology, there are genuine innovators emerging. And what I want to convey to businesses and bankers is, what was the underlying technology that Marc showed me or tried to show me in that white paper? It is just software, the latest and coolest software, which will enable us to do things we have never done before. Can this software be used for both good and bad? Yes, both, like all software. So, I would not disparage it in that way.

The final point is that these technologies are being developed in the United States. I am not just referring to the Stanford University campus; I believe that the most talented engineers from Europe and around the world still come to the United States to try to build these things. My view is that building it here gives us the opportunity to enhance productivity and create something very special over the next decade.

Despite global challenges, Warsh remains bullish on the U.S.

Peter Robinson:

Kevin, one last question. When you returned to Manhattan, you worked with one of the greatest investors of the past half-century, Stanley Druckenmiller. You are considered a macro research firm, focusing on large global trends.

I know you are well-versed in the global situation. Now, we are seeing growth in India and an increase in its market openness. We are even witnessing signs of genuine endogenous growth in Sub-Saharan Africa, such as in Nigeria and Kenya, which for decades have been considered troubled regions. Despite all this, you remain bullish on the United States. Why is that?

Kevin Warsh:

Certainly. I would like to make a few points. First, you mentioned that the United States is the innovator of almost all these new technologies. Could these technologies be applied elsewhere? Of course. But the most talented people in the world still want to come to the United States, and the most talented Americans also want to stay here and develop.

Secondly, I believe that economic policy over the past six months has been moving in a better direction than before. Economic policy is not perfect and never will be, but the American people are ready to shed the shackles they have been bearing for so long.

Among all the policies we have discussed, we have not yet mentioned the ‘regulatory tax’ that has severely damaged domestic growth in the United States over the past decade. I believe this tax is being gradually eliminated, partly due to the productivity revolution we discussed earlier. I think the ability of people, especially Americans, to adapt to new technologies and thrive is underestimated, and this ability is very real.

This may sound overly optimistic to some, but it is supported by the micro-foundations of macroeconomics, which is our social culture: a willingness to take risks and to try again after failure. This spirit is practiced more frequently in the United States than anywhere else. This kind of thing does not happen at the same speed in France or Germany. Therefore, when we eliminate the ‘regulatory tax’ and restore some of the effective domestic policies from the past, it will be an incredibly exciting moment.

Given that we are reforming existing institutions, I am willing to bet on the upside potential of domestic growth. I also believe that the central bank will address inflation and achieve price stability once again. At that point, other parts of the world may still dislike us, but they will look at the United States again and conclude that, despite the criticisms, their economy is growing faster, and that is where we should invest.

Peter Robinson:

Kevin Warsh, thank you very much.

Kevin Warsh:

Thank you, Peter. It’s an honor to be back on the show.

Edited by Danial