On 6 March, 2025, the European Council—the heads of government of EU member countries plus its President and the President of the European Commission—approved a new €800 billion defense package, ReArm Europe. A central element of the plan is to allow member states to increase public defense spending by up to 1.5 percent of GDP over at least four years, an amount equal to €650 billion. The other €150 billion will come from a new supranational borrowing program, SAFE (Security Action for Europe), the proceeds of which the Commission will use to reinvest in defense loans to member states. Alongside the public spending this enables, regulatory authorities and the European Investment Bank will prioritize lending to defense firms, seeking to attract private investment in the weapons industries.

These decisions appear to mark a paradigm shift for Europe’s foreign and defense policy, with significant implications for the global balance of power. Rooted in the 1957 Treaty of Rome and its amendments—at Maastricht in 1992, Amsterdam in 1997, and Lisbon in 2007, among others—the European Union has evolved into a partial state. It is a monetary union with a continental currency and central bank; a fiscal confederation of fragmented tax-and-spending policies, limited by treaty; and it does not have a fully integrated defense or foreign policy. Decision-making in these areas has been ceded to the European Council and the European Commission, which means it requires unanimity among member states, slowing down EU action or allowing a single member to block key initiatives. Defense remains a national competence, meaning the EU lacks its own standing army, while NATO continues to serve as the primary collective defense framework for most EU countries, particularly since many EU member states are also NATO members.

The main justification for the EU’s dramatic reorientation toward defense is the proliferation of threats to European security emerging from Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. The Commission also frames this fiscal-policy shift within a broader narrative highlighting the potential economic benefits that European rearmament could bring to the bloc’s stagnating economies. “EU countries will be facilitated to make the necessary investments in our defense capabilities and industry,” remarked Commissioner for Economy and Productivity Valdis Dombrovskis, the former finance minister for Latvia. “This will also boost economic growth, drive innovation and create jobs.” The mechanism for increasing public spending on weapons is to exempt member states from the EU’s Stability and Growth Pact, which since 1997 has limited national fiscal deficits to 3 percent of GDP and total national debts to 60 percent of GDP.

Neither the European security nor economic justification is entirely convincing: assessments of Russian military strategy give no indication of a direct threat to EU and NATO member states, and combined with austerity in other economic spheres, the prospects for military investments reviving Europe’s deteriorating economic model remain uncertain. Rather than defense or growth, ReArm Europe aims to enhance Europe’s geopolitical power and prestige within a volatile international order. While the geopolitical and economic impact of rearmament strategy remains uncertain, one outcome is already clear: national budgets will take on new debt burdens, and cuts to social and other public spending are likely to follow.

Europe’s geostrategic ambiguity

Military spending within the EU has steadily declined over the past fifty years. Under the US military umbrella, EU member states exhibited reduced demand for weapons, a lack of long-term defense procurement planning, and a shrinking defense industrial base.

The turning point came in 2014 with the overthrow of former Ukrainian President Viktor Yanukovych following the Maidan protests. The outbreak of civil war between Kyiv and the self-proclaimed people’s republics, followed by Russia’s annexation of Crimea, marked the beginning of a shift in Europe’s defense posture. Russia’s 2022 invasion prompted EU countries to ramp up their combined military spending from €214 billion in 2021 to €326 billion in 2024.

More recently, Donald Trump’s reelection appears to be the catalyst for rearmament. Speaking to the Munich Security Conference in February, for example, Vice President J.D. Vance urged Europe to “step up in a big way” to ensure its own defense. At the same time, the US-led negotiations with Putin over Ukraine have completely excluded European leaders. These events have made it clear that Europe’s ability to project geopolitical power will depend entirely on the strength of its collective military capabilities.

In a March 2025 Joint white paper, the Commission argues that in an era marked by escalating threats and intensifying systemic rivalry—particularly from Russia and China—Europe must adopt a more strategic and assertive stance. The paper estimates that Russian defense spending will reach 9 percent of GDP in 2025, surpassing the EU’s defense budget in purchasing power parity. It claims that if Russia succeeds in Ukraine, its “territorial ambitions” will further pose a long-term threat to European security. Failing to meet this threat, it warns, would leave the continent increasingly vulnerable to manipulation by powerful economic, technological, and military blocs competing for global influence.

At the same time, the Commission white paper highlights that NATO remains the cornerstone of the collective defense of its members in Europe. EU-NATO cooperation is an indispensable pillar for the development of the EU’s security and defense dimension. Unsurprisingly, a recent NATO analysis echoes the Commission’s warnings about Russia, isolating the Alliance’s eastern neighbor as its most significant and direct security threat. It maintains that Putin seeks to fundamentally reconfigure the Euro-Atlantic security architecture by rebuilding and expanding Russian military capabilities and continuing its airspace violations.

Assessing Russia’s strategic objectives

Russia’s expansionary ambitions across the continent, however, are far from certain. The white paper offers little clarity regarding whether the Commission’s plans are based on the assumption of a Russian annexation of all of Ukraine, or whether either party is preparing for military action in the Baltic states, Poland, or Finland. Notably, it also omits any discussion of potential diplomatic avenues for de-escalating tensions with Russia, marking a sharp departure from the EU’s long-standing tradition of prioritizing dialogue and negotiation. In 2019, a RAND corporation report identified five objectives for Russian foreign policy: regime survival and internal stability; preserving its great power status; pursuing economic prosperity (likely through greater cooperation with Europe); maintaining dominance over former Soviet states (including the non-Baltic former Soviet countries in Central Asia: Belarus, Ukraine, Moldova, Georgia, Armenia, and Azerbaijan); and blocking EU & NATO enlargement, particularly within its perceived sphere of influence.

In 1997, US president Jimmy Carter’s former national security advisor Zbigniew Brzezinski wrote that while “Russia, despite its protestations, is likely to acquiesce in the expansion of NATO … to include several Central European countries [but] will find it incomparably harder to acquiesce in Ukraine’s accession to NATO, for to do so would be to acknowledge that Ukraine’s destiny is no longer organically linked to Russia’s.” In fact, the RAND report notes that in 2007, Putin described NATO enlargement as “a serious provocation that reduces the level of mutual trust” and expressed concern about NATO bases near Russia’s border. Similarly, in 2016, Russian Foreign Minister Sergey Lavrov wrote that the choice to pursue NATO enlargement “is the essence of the systemic problems that have soured Russia’s relations with the United States and the European Union.” Supporting Lavrov’s claim, declassified documents now show that Mikhael Gorbachev received security assurances against NATO expansion from Bush, Genscher, Kohl, Mitterrand, and Thatcher.

Have Russian aims significantly shifted since 2019? The Intelligence Outlook of the Danish Intelligence Service published in January 2025 comes to no clear conclusions. The Danish argue that “Russia has ambitions to be a dominating power in a new world order.” However, they add that “Putin’s end goal will probably be the creation of a political and cultural space in which Russia will be free to dominate the security policy of Ukraine and Belarus.” The report does not convincingly explain how attacking a NATO country would advance Russia’s foreign policy objectives—particularly given that, after three years of war in Ukraine, Russia has struggled to break through Ukrainian defenses or achieve a decisive military advantage. The western European intelligence agency is sure to hold open the door to defensive rearmament, writing that “Russia will become more willing to use military force against NATO countries if it believes that NATO either is unable to maintain its military superiority, does not respond to Russia’s military activities, or no longer presents a united front.” In reality, as the report highlights, Russia’s limited success in executing large-scale, coordinated ground offensives suggests that it possesses neither the strategic intent nor the military capability to launch a war against a NATO country.

A new European growth strategy

Rather than an acute security threat, Russian expansion is being strategically instrumentalized by political elites to increase the military power of Europe and especially of Germany. The new German Chancellor, Friedrich Merz, has recently vowed to make the Bundeswehr “the strongest conventional army in Europe” as well as to deploy soldiers beyond its border, moving troops into Lithuania to defend its European neighbor.)NATO’s force structure() in Eastern Europe, Germany serves as the framework nation for the battlegroup stationed in Lithuania. For Germany, this expansion comes with economic benefits. As Merz ()announced(), “Lithuania placed an order for forty-four Leopard 2 main battle tanks under a Bundeswehr framework contract last year,” along with Rheinmetall building a modern production facility for artillery ammunition in Lithuania.” class=”footnote” id=”footnote-2″ href=”#footnote-list-2″>2

The premise is that EU countries are significantly increasing their military power to revive the EU sluggish economic performance. Since 2010, the EU has been on a downward economic trajectory triggered by the great financial crisis of 2008 and manifesting as a debt crisis in the southern periphery of the Eurozone. The fiscally “prudent” countries of the EU under the leadership of Germany imposed punitive austerity policies on countries like Greece, Spain and Cyprus, plunging them into recession, impoverishment, rising inequality, and disinvestment. Following that, lockdowns and supply chain disruptions during the Covid-19 pandemic pushed EU countries into a recession and exposed the vulnerabilities in the supply of essential goods caused by the outsourcing of production and deindustrialization.

The war in Ukraine has also exposed Europe’s reliance on foreign energy, exacerbated by the slow green transition. This led to higher costs for consumers and businesses and contributed to Germany’s deindustrialization, as its competitiveness depended a lot on cheap Russian gas. EU GDP growth reached only 0.4 percent in 2023 and an expected 1 percent in 2024. Germany, the once industrial powerhouse of Europe, has seen a decline in export market shares compared to other advanced economies and remained in recession throughout 2023 and 2024. France, the other partner of the once powerful Franco-German axis, is also facing economic challenges, with government debt standing at 111 percent of GDP in 2024—13 percentage points above its pre-Covid level—and expected to rise further. In response, French Prime Minister Michel Barnier has proposed a strict 2025 budget with €60 billion in tax hikes and spending cuts, including new taxes on electricity and air travel.

According to EU leaders, the heart of the continent’s economic crisis is its growing productivity and innovation gap compared to the US. In key sectors like clean technologies, artificial intelligence, electric vehicles, and telecommunications, China also continues to outpace Europe. Notably, only four of the world’s top fifty tech companies are European. This innovation and productivity deficit presents a significant obstacle to achieving a swift and equitable green and digital (“twin”) transition.

While this lag reflects longstanding internal policy failures, the conventional diagnosis about the causes of low productivity and innovation has only recently begun to acknowledge its deeper origins in European fiscal policy. In the southern periphery, the austerity policy legacy of the Eurozone crisis has reduced investment, constrained potential output, curtailed productivity growth, and exacerbated inequalities. Meanwhile, Germany, bound by its strict (“black zero”) fiscal policy, failed to boost domestic demand, invest in infrastructure, or support disruptive innovation, instead relying on the past advantages of its established champions and captive export markets in the Eurozone. Moreover, the EU has traditionally followed a hands-off economic approach, relying on free markets and existing strengths rather than actively shaping industrial policies. This approach has proven insufficient in recent decades, as demonstrated by the missed opportunity in the photovoltaic industry.

It was in this context that Mario Draghi delivered his 2024 speech to the European Parliament. Draghi argued that:

Of all the major economies, Europe is the most exposed to [geopolitical] shifts. We are the most open: our trade-to-GDP ratio exceeds 50 percent, compared with 37 percent in China and 27 percent in the United States. We are the most dependent: we rely on a handful of suppliers for critical raw materials and import over 80 percent of our digital technology. We have the highest energy prices: EU companies face electricity prices that are 2–3 times higher than those in the United States and in China. We are severely lagging behind in new technologies. And we are the least ready to defend ourselves: only ten member states spend more than or equal to 2 percent of GDP on defense, in line with NATO commitments.

The Draghi Report suggests substantially increasing the aggregation of defense demand among groups of member states and pursuing further standardization and harmonization of defense equipment. Additionally, it calls for the establishment of EU-level funding to support the development of the EU’s defense industrial capabilities. The Council is now proposing to enable the Commission to carry out all these measures. Draghi’s argument for the spillover effects of defense R&D on other sectors of the economy, as well as on privately funded R&D, has likewise found broader intellectual and academic purchase in Europe. In February 2025, the influential Kiel Institute for the World Economy published Guns and Growth: The Economic Consequences of Defense Buildups, a report by the London School of Economics Professor Ethan Ilzetzki. The report argues that Europe-wide GDP will grow by 0.9 percent to 1.5 percent if defense spending increases from 2 percent to 3.5 percent of GDP. It highlights that a transient 1 percent of GDP increase in military spending could increase long-run productivity by a quarter of a percent—both through learning-by-doing and through R&D. Temporary and permanent military buildups, it argues, should initially be financed through public borrowing, with fiscal-structural measures like tax increases or expenditure cuts introduced at a later stage.

Employers’ associations, think tanks, and rearmament

European political and economic leaders viewed the Draghi Report as a guiding blueprint for reigniting the EU economy and strengthening its competitiveness. This is understandable, given that the report was overwhelmingly influenced by corporate interests, with 65 percent of written input coming from businesses and only 5 percent from civil society. The two largest European employers’ associations, the European Round Table of Industrialists (ERT) and BusinessEurope, welcomed it enthusiastically, with ERT recently informing the Council how Poland’s strong record and leadership—the Council Presidency sits with Poland until July— can accelerate momentum toward rearmament across the EU.

Indeed, Europe’s largest companies are set to hugely benefit from the spending package. The European Aerospace, Security, and Defense Industries Association (ASD) republished the Kiel report on its website, commenting that it “challenges conventional wisdom that defense expenditure is a financial burden on states, arguing instead that such investment can serve as a catalyst for economic growth, technological innovation, and sustained productivity.” In a February 2025 letter to the German Chancellor, his ministers, and the country’s major party chairmen, the presidents of the Federal Association of the German Security and Defense Industry (BDSV) and the Federal Association of the German Aerospace Industry (BDLI) advocated for a stronger focus on domestic defense companies—“Buy European”—in the coming rearmament initiative. The German Association of Industrialists (BDI), in its Agenda for Growth, published ahead of the German federal elections, highlights the threat posed by Russia. In France, Patrick Martin, the President of the Movement of the Enterprises of France (MEDEF), stated in a televised interview that “we are in a good position in France to have world champions in the defense industry—I’m thinking of Thales, Dassault, Naval Group, and Safran … We must support Ukraine in this tragic situation.”

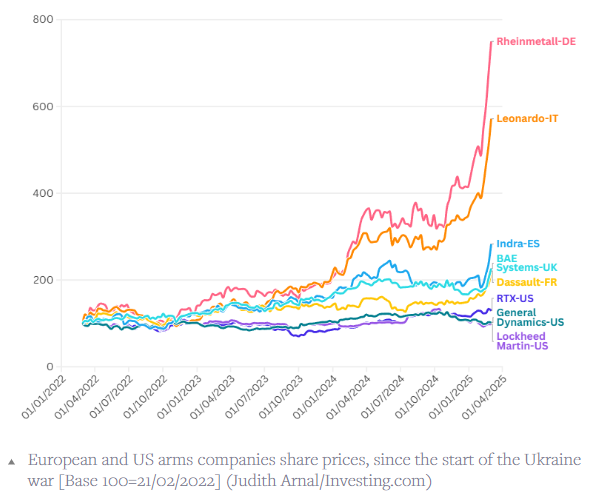

The exuberance for the economic stimulus of weapons production for corporate profits can be seen in the graph below showing the stock market performance of Europe’s leading defense manufacturing firms since January 2022. Share prices began the swing upward during 2023. For half the firms—Rhinemetall, Leonardo, Indra, and BAE Systems—share prices during 2024 were double or triple their pre-invasion values.)From welfare to warfare: military Keynesianism – Michael Roberts Blog().” class=”footnote” id=”footnote-5″ href=”#footnote-list-5″>5 Then the real speculative boom came. In February 2025, four months after Draghi’s competition report and two months after Donald Trump’s victory in the US presidential election, leading Brussels think tank Bruegel proposed “an annual defense spending hike of at least €250 billion in the short term.” Speaking through the Financial Times, Bronwen Maddox, director of Chatham House, declared “defense” spending to be “the greatest public benefit of all” because it is necessary for the survival of “democracy” against authoritarian forces. After Von der Leyen’s Commission announced ReArm Europe just weeks later, share prices catapulted to new speculative highs. Leonardo’s shares doubled in price over the previous summer. Rheinmetall, already quadruple their pre-invasion value before the new year, doubled again over eight weeks.

But the advertised benefits are not just for capital. Since the outbreak of the Ukraine war, global defense companies are recruiting workers at the fastest rate since the end of the cold war as the industry seeks to deliver on order books that are near record highs. Rheinmetall, Europe’s top ammunition maker, has proposed taking over idle Volkswagen plants to produce tanks, in addition to converting two existing automotive parts plants to produce defense equipment. Hensoldt, which makes the TRML-4D radar systems being used by Ukraine in its war with Russia, is in talks to take on around 200 workers from major auto parts suppliers Bosch and Continental. “We are benefiting from the difficulties in the automotive industry” Hensoldt’s chief executive Oliver Doerre told Reuters, adding that further investment could more than double annual production of the TRML-4D.

European trade unions are also contributing to the construction of the war economy narrative. In a letter addressed to von der Leyen and European Council President António Costa just after their announcement, the European Trade Union Confederation (ETUC) urged that the increase in continental defense spending be understood as an opportunity to embrace a “broader concept of security” including “social objectives.” To achieve these, the ETUC reminded the Commission and the Council of its demand for an urgent suspension and reform of the EU’s economic governance rules “in order to allow for the necessary investments” in “quality jobs, just transitions, industrial policy, strong public services, social protection, security and other EU objectives.” Where growth occurs through defense spending, the ETUC demands “strong social conditionalities” to ensure “full respect of workers and trade union rights.” While the German Trade Union Confederation is notably more cautious on government spending—“loosening the debt brake … remains highly problematic,” its leaders write, because it “creates the possibility of arbitrarily increasing spending along a completely open-ended scale”—it too recognizes “the need to make increased efforts in Germany and Europe to become more capable of defending ourselves together.”

But there are different reasons to question the notion that amplified military spending will resolve Europe’s persistent economic stagnation. For Europe to fully capitalize on this stimulus, it is essential that a larger proportion of defense spending remains within the EU. At present, around 80 percent is sourced from non-EU suppliers. In fact, between 2020 and 2024, the United States accounted for 64 percent of arms imports by European NATO members—a significant increase from 52 percent in the 2015–2019 period. The import dependency on US producers is larger especially for modern weapons systems. This situation must be taken into consideration in evaluating the broader claims about the benefits of defense spending-financed economic growth. The technological spillovers and productivity gains suffusing current rhetoric will only be generated by domestic production. But even if policy succeeds in addressing this technological backwardness and dependency, shortening development times from their current Kiel-sponsored forecasts, there are reasons to question the efficiency of this growth strategy. Modern weapons production depends on advanced manufacturing techniques that require relatively little labour, resulting in lower economic multipliers compared to investments in sectors like health, education, or green energy. It generates fewer jobs per euro invested and has limited impact on enhancing the overall productive capacity of the economy.

The quest for hegemony

The hegemonic project centered on ReArmEU is still taking shape. What is already visible, however, is that Russia’s invasion of Ukraine has been strategically leveraged to justify increased military expenditure and to enhance Europe’s geopolitical standing. In addition, the current rearmament drive seems to have provided Germany with an opportunity to strengthen its military presence in Europe and gradually transition from a soft-power to a more-assertive, hard-power role within the Community. The social force at the heart of this initiative is European industry, which has been facing increasing competition from China and the United States and stands to gain substantially from such a program. However, the preferential treatment of purchasing European-produced weapons will mostly benefit the German, French, and Italian producers, who are already seeing their orders and share prices increasing.

On the political level, the project is initiated by segments of the political elite—notably the Social Democratic and Christian Democratic/Liberal parties in Brussels, Berlin, and Paris—which are facing significant domestic political pressure from the far right. Lacking a substantive geopolitical assessment of the true nature of the Russian threat—and without genuine efforts toward diplomatic de-escalation—these elites exploit the threat narrative to gain domestic political leverage, while also keeping in mind the revitalization of their own industrial base. In parallel, the Brussels bureaucracy, particularly the European Commission, is likely to see its power increase, as it will be responsible for coordinating procurement and raising funds on financial markets. So far, employers’ associations have been following and supporting the political initiatives, although they have not yet stepped forward to shape a public narrative. That role has been taken on by think tanks, which are beginning to offer the necessary ideological justification and to develop in detail the various dimensions of the project. Finally, the major trade unions in Germany and Brussels are likely to play their part by promoting the view that under certain conditionalities the war economy can also benefit workers, thereby ensuring broader social acceptance.

But who will ultimately bear the cost for rearmament? The new Security and Action for Europe (SAFE) instrument will provide loans—not grants—backed by the EU budget. This implies that the debt burden will fall squarely on national budgets, exacerbating public debt in member states. Moreover, given the EU’s continued adherence to economic orthodoxy and neoliberal principles, these rising expenditures will likely be offset by retrenchments in the welfare state. That could mean pension reductions, healthcare cuts, and wage constraints—all presented as necessary sacrifices, made in the name of homeland security and European unity. After all, there is a price to be paid for defending democracy, as Starmer’s Labour government has been teaching the British people. “When speaking about the war effort,” MEDEF president Patrick Martin explains, “I am not saying that we should raise the legal retirement age in France to seventy. But it does mean that there is a consensus in the country, a shared awareness that this very serious situation requires exceptional measures.”