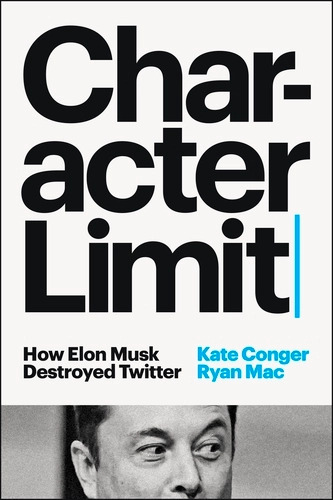

![]() Kate Conger and Ryan Mac. Character Limit: How Elon Musk Destroyed Twitter. Penguin Press, 2024. 480 pp. Hardcover $32.00.

Kate Conger and Ryan Mac. Character Limit: How Elon Musk Destroyed Twitter. Penguin Press, 2024. 480 pp. Hardcover $32.00.

If you are a Twitter/X user or former user who watched Elon Musk’s messy takeover of the social media company unfold and found yourself wondering what the hell just happened, Character Limit: How Elon Musk Destroyed Twitter (2024) has more than 400 pages of answers. Co-written by Kate Conger and Ryan Mac, New York Times technology journalists who have been following the machinations of Musk and other tech-industry billionaires for years, the book combines real-time reporting with extensive interviews and public records research. The duo trace the management crisis at Twitter that opened the door to a hostile takeover, Musk’s growing addiction to the platform, his impulsive and costly decision to acquire the company, and his paranoid and ineffective management, running parallel to his growing embrace of the political right in the US and elsewhere. The result is a carefully reported and gripping tale of how Twitter and Musk collided, with disastrous results for most of the company’s employees, many of its users, and its newest investors—a tale that nonetheless does not quite meet the political moment.

If you are a Twitter/X user or former user who watched Elon Musk’s messy takeover of the social media company unfold and found yourself wondering what the hell just happened, Character Limit: How Elon Musk Destroyed Twitter (2024) has more than 400 pages of answers. Co-written by Kate Conger and Ryan Mac, New York Times technology journalists who have been following the machinations of Musk and other tech-industry billionaires for years, the book combines real-time reporting with extensive interviews and public records research. The duo trace the management crisis at Twitter that opened the door to a hostile takeover, Musk’s growing addiction to the platform, his impulsive and costly decision to acquire the company, and his paranoid and ineffective management, running parallel to his growing embrace of the political right in the US and elsewhere. The result is a carefully reported and gripping tale of how Twitter and Musk collided, with disastrous results for most of the company’s employees, many of its users, and its newest investors—a tale that nonetheless does not quite meet the political moment.

Here I’ll pause for a confession: I found this book difficult to read. While reading the book in the spring, I was bombarded with news about Musk’s role in the federal government. The more I learned, the less stomach I had for his antics at Twitter. This is through no fault of Conger and Mac’s narrative skill, which turned an event I watched unfold in real time into a genuine page turner. Had I read the book when it first came out in fall 2024, that might have felt like enough. At that time, I thought of the “Department of Government Efficiency” (DOGE) as the kind of blustering Trump-speak that was unlikely to become reality. But by spring 2025, as news spread about how Musk and his so-called DOGE officers were actively and unconstitutionally dismantling the federal government, reading a book about Musk—even one that promised some insight about how we got here-–became an increasingly aversive task. The result was a book that demonstrates exceptional reporting and storytelling, but that was ultimately unsatisfying. If the experience of reading a book can change so dramatically with the context of just a few months, what was the book missing in the first place?

Character Limit does a fine job of telling the story its authors set out to tell. The first part of the book, which the authors term “Act I,” offers an overview of the development and growth of Twitter. Conger and Mac take readers inside the company’s longstanding internal struggles with leadership, financial growth, and debates over content management. This section also traces Musk’s growing presence on Twitter and his interest in taking more control, culminating in his 2022 move to stage a takeover. The book’s Act II, its most compelling, tracks Musk’s efforts to buy the company, assemble the funding to make his outrageous $44 billion offer possible, and the legal and economic consequences for all sides. Act III, the final act, is an account of Musk’s management of Twitter once his purchase was complete. For those who followed the saga on Twitter itself, many of the anecdotes will be familiar: the chaotic rollout of the Twitter Blue badge system, stories of engineers sleeping in their offices and having to bring their own toilet paper into the office, commands for developers to print out every line of code for Musk to review-–followed almost as quickly by panicked commands to stop printing and start shredding so as not to run afoul of the Federal Trade Commission. It all starts to feel incredibly stupid, and yet it cannot be laughed off. The effects on individual people’s lives are sickening, even more so when paired with Musk’s seeming disinterest in the harm he causes.

Conger and Mac are clearly fascinated by Musk, and it is not difficult to see why. The authors repeatedly demonstrate that the billionaire entrepreneur is either unwilling or unable to understand that his personal experience-–either on Twitter or more generally-–does not reflect most people’s, and this blindness to his own myopia is both intriguing and, thanks to his current political power, terrifying. Musk is a supposedly brilliant mind who does not fully understand the company he has purchased or what it takes to operate it. His bland response of “interesting, interesting” every time an employee tells him something he clearly had never considered becomes almost a comedic cadence in the book. Musk has so bought into his own narrative that he refuses to trust other people’s expertise. Instead, he sinks into paranoia and forces his employees to come up with increasingly absurd solutions to problems he insists are real.

Of course, Musk is not the only character in this tale, and few people escape scrutiny either for their role in Twitter’s struggles or their enabling of Musk’s pursuits. But it is Musk himself whose portrayal is most unflattering; Roald Dahl could not have written a more comically loathsome human. Musk seems to have imagined that he could buy the candy factory and install himself as tech’s Willy Wonka, but in Conger and Mac’s telling he comes off as all four bratty golden ticket winners combined: the greed and insatiable appetite of Augustus Gloop, the spoiled and selfish wealth of Veruca Salt, the pointless competitive focus of Violet Beauregarde, and the obsession with a fictional video game masculinity of Mike Teavee.

Twitter HQ offices in San Francisco, CA, May 2023. Photo by Filip Troníček. No changes were made to the image, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons.

The book unfolds so effectively as a drama that I repeatedly flipped to the endnotes to see how Conger and Mac had done their reporting. Here, though, I was frustrated, because only some of the journalists’ sources–public records, tweets, and published articles and books–are cited. In addition to relying on court documents, social media posts, and employees’ and executives’ public statements, Mac and Conger inform readers that they did “interviews totaling more than 150 hours with nearly 100 people” ranging from “current and former employees for Twitter, X, Tesla, and SpaceX; lawyers, bankers, and other associates who worked for both sides…as well as friends and acquaintances of Musk, [former Twitter co-founder] Jack Dorsey, and other Twitter executives.” (441) It is not hard to believe them, given their detailed narrative accounts even of conversations behind closed doors. Many of the authors’ interview subjects likely wanted to remain off the record, understandable given what the book demonstrates of Musk’s penchant for both litigation and revenge. Likewise, I realize that citation practices for journalists and historians differ. But for the reader who is curious to understand how Mac and Conger take us into some of the most private rooms as events unfold, it’s frustratingly unclear how they reported their accounts.

While the dramas of Musk’s erratic behavior and increasingly paranoid management style make for good storytelling and foreshadowing for his role in the federal government, some of the most intriguing elements of the book are not personal dramas or boardroom arguments, but the larger structures that allowed Musk to run roughshod over Twitter in the first place. These are numerous: the financial systems that enabled Musk and others to amass vast fortunes by facilitating online payments; banking structures that allowed Musk unparalleled access to investment funds; laws insufficient in the face of extreme wealth; and governmental regulations lagging far behind big tech developments. Each of these is only glancingly covered in Character Limit, as context for Musk’s actions. It is unfair to criticize a book for not being a different book altogether, and I do not mean to do so here. But I wished for a narrative that was less interested in the minute details of Musk’s takeover and more willing to dive into the circumstances that allowed these events to occur in the first place. Otherwise, what emerges is a sort of great man theory of history that gives Musk more credit than he deserves. By focusing predominantly on Musk’s individual actions and motivations, the authors unintentionally buy into Musk’s own narrative that he is a once-in-a-lifetime technological and business mind. To put it in Musk’s preferred videogame parlance, Musk is making all the moves in this game, and other people are nothing but NPCs, or “non-player characters.” In reality, Elon Musk is not a historical aberration, but someone who has simply been able to take advantage of the systems around him. As the consequences of Musk’s prominence in federal government and international affairs continue to unfold, a better understanding of how he was able to occupy such a position in the first place feels urgent.

Two scenes continued to play in my mind long after I had finished the book. In the first, after Twitter Human Resources executives warn Musk and his lawyer, Alex Spiro, that their rushed layoffs are likely to violate both contracts and labor laws, the two men wave away talk of lawsuits and fines. “I’m used to paying penalties,” Musk is reported as saying. (277) Spiro later tells the Twitter legal team that Musk was unbothered by “extraordinary amounts of legal risk.” (323) The idea that what limited legal consequences have applied to Musk have almost no effect on a person with his wealth suggests that something has fundamentally broken in the balance of wealth and regulation in the United States. Now, of course, the office Musk inspired and led, the so-called “Department of Government Efficiency,” is making great strides in limiting–or eliminating altogether the regulations that have hampered Musk’s business ambitions, making it even easier for him to shrug off any consequences. The second moment comes near the end of the book. Yoel Roth, a former content moderation executive at Twitter who had endured death threats and was forced to sell his house at a loss after Musk unleashed a Twitter mob falsely accusing him of being a pedophile following his resignation, is asked what advice he would give Twitter’s new CEO, Linda Yaccarino (who has since stepped down from her position). Roth’s response is chilling: “‘If not for yourself, for your family, for your friends, for those that you love, be worried,’ Roth responded. ‘You should be worried. I wish I had been more worried.’” (420)

The image of Musk as a man unbothered by legal penalties and enthusiastically cruel in seeking revenge on those who get in his way is undercut by the book’s final paragraphs. I do not envy Conger and Mac having to decide how to end at all, as events continued to unfold as the book went to print and since its publication. But they opted to strike a note similar to the end of the 2010 film The Social Network, focusing on Musk’s psychic flaws and failure to get Twitter to love him: “A man allergic to criticism had bought himself the largest audience in the world, and hoped for praise.” (436) After spending so much of the book demonstrating Musk’s self-centered, oblivious harm, the decision to end with this glimpse of his humanity is jarring. To me, it reads as Conger and Mac pulling their punches, and the choice demonstrates one of the problems of putting so much emphasis on one individual’s actions. The temptation to end with this note of poetic melancholy is great. But as compelling as the idea of Musk as some great tragic villain might be, I am less interested in what motivates Musk to inflict misery on so many other people. I want to understand how a person like Musk was able to inflict so much misery in the first place. If you want a play-by-play of Musk’s Twitter takeover with plenty of insider information, Character Limit will satisfy. But for this moment, I wanted a book that offered readers analysis beyond the limits of Musk’s character.

And if Conger and Mac are reading this, a plea from a historian: save those interview notes and donate them to an archive when you retire. Future historians will thank you.

Twitter vs. CNN in Wisconsin, February 2011. Photo by Matt Baran. No changes were made to the image, CC BY-SA 2.0, via Wikimedia Commons.