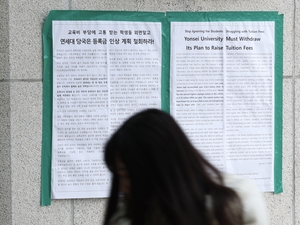

A student walks past protest posters at Yonsei University in Seoul urging the school administration to cancel its planned tuition increase in this photo taken on Jan. 20, 2025. Despite student opposition, the university approved its first undergraduate tuition hike in 15 years just four days later, raising fees by 4.98 percent. (Citizens’ Alliance for Free and Standardized University Education)

A student walks past protest posters at Yonsei University in Seoul urging the school administration to cancel its planned tuition increase in this photo taken on Jan. 20, 2025. Despite student opposition, the university approved its first undergraduate tuition hike in 15 years just four days later, raising fees by 4.98 percent. (Citizens’ Alliance for Free and Standardized University Education) Young South Koreans are borrowing more money than ever for college, while their chances of landing a stable job grow slimmer.

New data from the Korea Student Aid Foundation reveals that student loan borrowing surged to 2.11 trillion won ($1.44 billion) in 2024, the highest figure in nine years. This marks an 11 percent jump from the previous year’s total of 1.89 trillion won. The last time borrowing exceeded 2 trillion won was in 2015.

The spike comes as job opportunities for young people are drying up. According to Statistics Korea, the number of employed South Koreans aged 15 to 29 fell by 173,000 in June compared to the same month last year. Youth employment has declined for 32 consecutive months.

The Ministry of Employment and Labor reported that in June, there were only 39 job openings for every 100 job seekers, the lowest ratio for that month since the 1997 financial crisis.

Students struggle to repay loans without jobs

Job seekers take part in on-site interviews during the KOADMEX Job Fair 2025, part of South Korea’s digital medical equipment and healthcare industry expo, held at EXCO in Daegu on June 20. (Newsis)

Job seekers take part in on-site interviews during the KOADMEX Job Fair 2025, part of South Korea’s digital medical equipment and healthcare industry expo, held at EXCO in Daegu on June 20. (Newsis) At the same time, student loan defaults are increasing. The number of borrowers behind on payments for standard repayment loans reached 24,587 in 2024. That’s a 14 percent rise from the previous year and nearly 50 percent more than in 2021, when 16,669 borrowers were in default.

KOSAF operates two main loan programs. Income-contingent loans postpone repayment until a borrower’s income exceeds a threshold, while standard loans require repayment on a fixed schedule, regardless of employment. The latter has seen especially steep growth. Standard loan borrowing rose by 43.4 percent over the past three years, from 860.9 billion won in 2021 to 1.24 trillion won in 2024. ICL borrowing increased more modestly, from 795.3 billion won to 876.1 billion won in the same period.

South Korea’s leading job platforms are reporting steep drops in hiring. JobKorea said job postings from January to May were down 24.1 percent from a year earlier. Job ads specifically targeting recent college graduates fell 20.6 percent.

A March survey by Incruit, another recruitment site, found that only 65.6 percent of companies had confirmed hiring plans, the lowest figure in three years.

But KOSAF attributed the rise in loans to low interest rates and expanded eligibility policies, including extending ICL eligibility to graduate students in 2022. Local governments have also increased support, such as Gyeonggi Province’s interest subsidy program, which has benefited over 430,000 students since 2010.

Degrees costing more with lower pay-off

Meanwhile, tuition is rising. South Korea’s four-year universities raised tuition by an average of 4.1 percent in 2025. The OECD reported that government spending covered only 43.3 percent of higher education costs in South Korea as of 2020, far below the OECD average of 67.1 percent. The rest falls mostly on individuals and families.

In contrast, the wage premium associated with having a college degree remains low. University graduates earned 134.9 percent of the wages of high school graduates in 2021, trailing the OECD average of 142.6 percent for that ratio.

mjh@heraldcorp.com