For decades, the conflict between Algeria and Morocco over Western Sahara has dominated headlines and shaped regional politics. Officially, it is presented as a struggle over sovereignty, self-determination, and territorial integrity. But behind this carefully crafted narrative lies a deeper and more cynical truth: both regimes have long used this conflict as a tool of distraction, repression, and political survival.

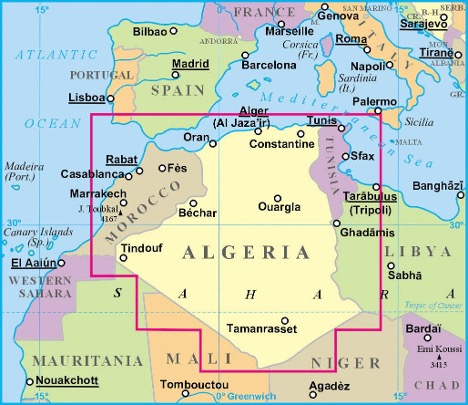

The roots of the Western Sahara conflict trace back to 1975, when Spain withdrew from the territory. Morocco moved to claim it, while Algeria supported the Polisario Front, which has called for an independent Sahrawi state. Since then, the two countries have remained locked in a political cold war, with closed borders and competing narratives. Yet, despite the passage of time, no real resolution has been pursued not because it’s impossible, but because both regimes benefit from the status quo.

Faced with economic crisis, widespread unemployment, and growing demands for reform, both regimes exploit the conflict to distract from their failures. Fear and nationalism become tools to deflect attention, while any challenge to official narratives especially in Morocco regarding Western Sahara or the monarchy, and in Algeria concerning political freedoms is swiftly punished. Dissent is not debated; it is silenced.

Language and religion have also been weaponized in this struggle. Both countries have built their national identities around Arab-Islamic unity, often at the expense of the region’s indigenous Amazigh (Berber) identity. While Tamazight has gained official recognition in recent years, it remains poorly supported in practice. Cultural rights are still treated as secondary or even subversive. Demanding education, visibility, or funding for Tamazight is often viewed as a threat to national cohesion. But this erasure is not accidental. It is political. Enforcing a single, dominant identity helps regimes impose conformity and eliminate alternative sources of legitimacy and resistance.

Another well-practiced strategy is the invention of constant external enemies. Both regimes regularly accuse foreign powers, NGOs, or especially the neighboring country, of plotting against the nation. This narrative allows them to discredit journalists, activists, and human rights defenders as “agents” of hostile forces, and justifies authoritarian crackdowns. Rather than addressing citizens’ demands, the state fights an imaginary war against invisible enemies often its own people.

But the real victims of this manufactured conflict are the ordinary people. Sahrawi communities remain caught in political limbo, trapped between occupation and exile, under surveillance and neglect. Amazigh voices are heard only when tolerated by the state. And young people in both Algeria and Morocco face joblessness, censorship, and shrinking horizons. The dream of unity and development is replaced by propaganda, fear, and silence.

Despite all this, one truth remains clear: Algerians and Moroccans are not enemies. They are victims of the same manipulation. They want the same things justice, democracy, freedom, and cultural dignity. It is time to reject the illusion of endless conflict, to resist the abuse of nationalism, and to open space for genuine dialogue and cooperation across the region.

We must stop asking who owns the land, and start asking who controls the silence. The real threat to the region is not across the border it is inside the palace.