Yestday I took an eight-hour bus tour to see the famed “golden circle” of tourist sights near Reykjavic in Iceland.. Wikipedia delineates what we saw:

The Golden Circle (Icelandic: Gullni hringurinn [ˈkʏtlnɪˈr̥iŋkʏrɪn]) is a tourist route in southern Iceland, covering about 300 kilometres (190 mi) looping from Reykjavík into the southern uplands of Iceland and back. It is the area that contains most tours and travel-related activities in Iceland. The term for the “Golden Circle” was a marketing tactic developed by the Icelandic Tourism board to improve travel.

The three primary stops on the route are the Þingvellir National Park, the Gullfoss waterfall, and the geothermal area in Haukadalur, which contains the geysers Geysir and Strokkur, which erupts every 10-15 minutes. Though Geysir has been mostly dormant for many years, Strokkur continues to erupt every 5–10 minutes. Other stops include the Kerið volcanic crater, the town of Hveragerði, Skálholt cathedral, and the Nesjavellir and Hellisheiðarvirkjun geothermal power plants.

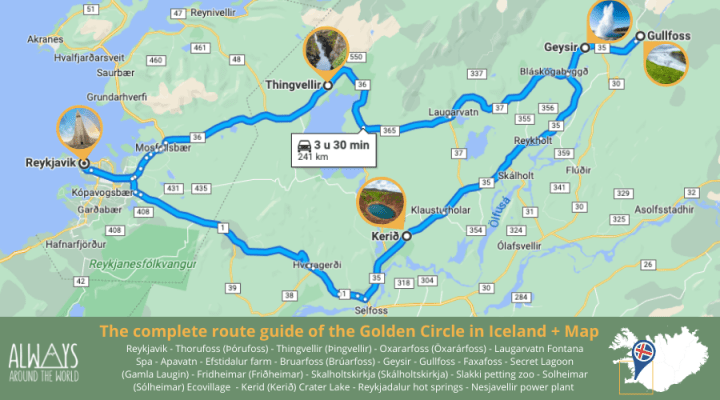

Below is a map from Always Around the World of the route we took, which involved about 7.5 hours of total travel and 270 km of driving. Sadly, we went by Keri∂ Crater (a sunken volcanic crater filled with an emerald-green lake), but didn’t have time to see it. We did, however, see lots of the Icelandic countryside, which is flat and grassy, both because it comprises farms but also because the terrain has been flattened by glaciers and the climate is not conducive to trees.

The three sights we visited were Thingvellir National Park, the site where the conjunction of two tectonic plates is most obvious in the world, Geysir, an area of geothermal activity with, yes, geysers, and Gullfoss, one of the most beautiful waterfalls I’ve ever seen (I haven’t been to Niagra).

First, the rift park:

Þingvellir (Icelandic: [ˈθiŋkˌvɛtlɪr̥], anglicised as Thingvellir) was the site of the Alþing, the annual parliament of Iceland from the year 930 until the last session held at Þingvellir in 1798. Since 1881, the parliament has been located within Alþingishúsið in Reykjavík.

Þingvellir is now a national park in the municipality of Bláskógabyggð in southwestern Iceland, about 40 km (25 miles) northeast of Iceland’s capital, Reykjavík. Þingvellir is a site of historical, cultural, and geological significance, and is one of the most popular tourist destinations in Iceland. The park lies in a rift valley that marks the crest of the Mid-Atlantic Ridge and the boundary between the North American and Eurasian tectonic plates.

I saw no remnants of its parliamentary history, but was delighted to see the signs of the two tectonic plates. I don’t know of any other place on Earth where their conjunction is so obvious. They are moving apart now, at about the rate your fingernails grow: about 1 cm per year. This movement has created a wide valley containing lake as well as numerous cracks in the earth created as the plates separate. These fissures are all parallel, running from northeast to southwest.

Here’s the rift valley, which we were told is abut 7 km across. You can see the mountains on the other side and the lakes in the valley, while I took the picture from above, on the North American plate:

Here are a few of the fissures in the ground nearby:

This is a big one that people walk through. I have to add that, according to our guide, this was the busiest tourist day this summer. Although it was a Monday, it was sunny and warm: 23º C (73.4° F), and I quickly took off all my outer layers except for a tee-shirt. As you can see below, there were tons of tourists about. It’s summer, July and August are vacation months for the locals, and many of the visitors were Icelandic.

Regardless, I was tremendously excited to see the actual results of plate tectonics, though I’ve seen them before (e.g., the Himalayas). But actually standing on an area where the plates are moving apart was, at least for me, a huge thrill.

On to Haukadalur with its geothermal activity and geysers (I’ve never seen a geyser although the U.S. has the famous “Old Faithful” in Yellowstone National Park).

The geothermal activity is clear even from the parking lot of the visitor center. Many of these small craters emitting steam also have bubbling hot water. (I have video but can’t post it here; more later.) There are ample warnings to stay away from the water, which is 80-100°C.

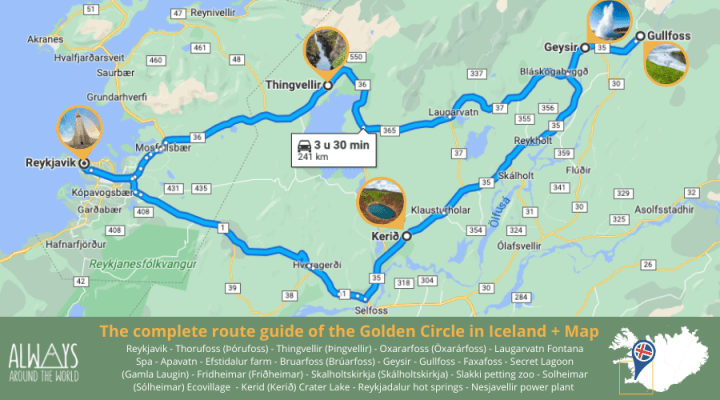

Below: the Icelandic geysers compared to others in the world. “Geysir,” the biggie, is no longer active, but Strokkur is, and erupts irregularly with an average about ten minutes. You can see the Strokkur isn’t that much smaller than Old Faithful, but Geysir, when it was active topped them all. I saw about four eruptions of Strokkur (see below). Old Faithful in the U.S. erupts about 20 times a day.

When I asked my guide where the big geyser was, she responded, “Just walk into that area. You’ll know.” And, sure enough, I did:

These people are waiting for Strokkur to erupt, which, as I said, does so irregularly with a mean of about ten minutes. Because the eruption takes only a second or two, you have to be ready, and it does tire your arms to hold your camera up, focused on the likely eruption spot. I got three shots, with the last missing the top of the largest eruption. It’s a pretty impressive sight (these are three separate eruptions):

And the biggie (I wasn’t prepared for the height):

This is a good YouTube video of what it’s like to be in the area and see the eruptions:

Despite the heat and sulfur, plants and moss grow near the hot effluent. Life is tenacious. Here’s one photo:

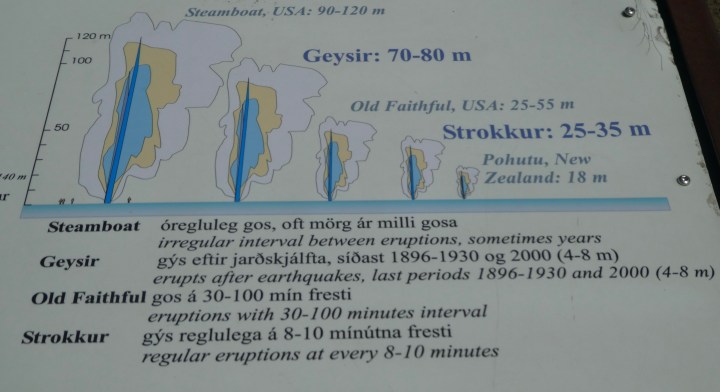

Finally, the waterfalls of Gullfoss, as explained in the sign below. Originally it was to be made into a hydroelectric plant, but the locals saved it. Now it’s part of a permanent conservation area:

From Wikipedia:

The Hvítá river flows southward, and about a kilometre above the falls it turns sharply to the west and flows down into a wide curved three-step “staircase” and then abruptly plunges in two stages (11 metres or 36 feet, and 21 metres or 69 feet) into a crevice 32 metres (105 ft) deep. The crevice, about 20 metres (66 ft) wide and 2.5 kilometres (1.6 mi) in length, extends perpendicular to the flow of the river. The average amount of water running down the waterfall is 141 cubic metres (5,000 cu ft) per second in the summer and 80 cubic metres (2,800 cu ft) per second in the winter. The highest flood measured was 2,000 cubic metres (71,000 cu ft) per second.

As it was a rare day of full sun, I had the luxury of seeing a rainbow at these lovely falls. The roar is impressive, and the falls go down in several steps. I have video but again you’ll have to wait to see that. But I’ve put a video below. First, a few photos I took of the falls. Notice the rainbow (and plethora of tourists):

Here’s a video which gives you a sense of what it’s like to be near this enormous waterfall: Even a gazillion tourists couldn’t drown out the roaring:

A plant I photographed nearby. Botanists: what is it?

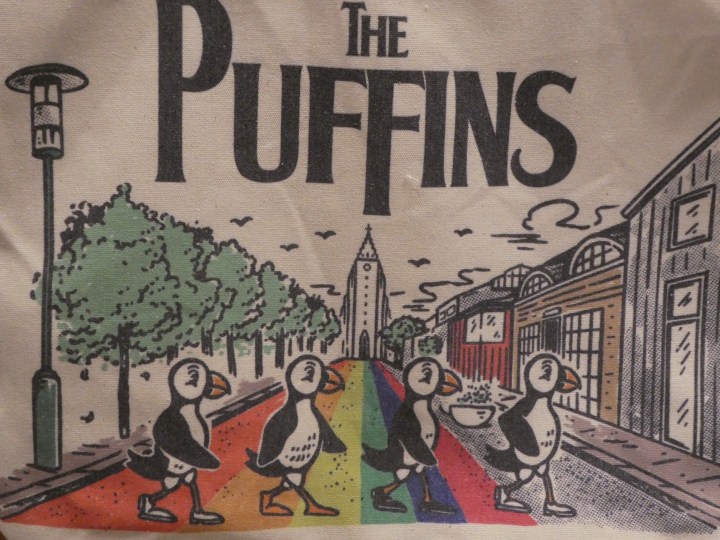

And three superfluous photos. First, a teeshirt in the gift shot at Gullfloss (all the tchotchkes are the same in all the shops). Notice the accuracy: the third puffin, which is Paul on the Abbey Road cover, is barefoot, just as Paul was:

Yesterday’s gull levitating a roll with its bill. The gull must have been magical:

And my post-trip reward: ice cream (hazelnut and crème brûlée). Guess what it cost? But, as Hemingway would say, ‘I deserved it, and it was good.”