While we tend to remember the big, loud classic war movies (Saving Private Ryan, Apocalypse Now, Dunkirk), there are plenty of quieter, stranger, and arguably more devastating works that don’t get enough attention. With this in mind, this list considers some lesser-known war movies that are still gems.

These are the war films that got lost in the shuffle, pushed aside by glossier productions or overshadowed by their political timing, or simply a little lost to time. The films below might not be iconic, but they all contain enough style or thoughtfulness to merit a viewing. They run the gamut from lean, mean action flicks to meditative war dramas.

10

‘The Ascent’ (1977)

Directed by Larisa Shepitko

“They’re afraid of the truth.” Set in the snowy wilderness of Nazi-occupied Belarus, The Ascent is one of the most spiritually harrowing war films ever made. It chronicles the ordeal of two Soviet partisans captured by German forces. Director Larisa Shepitko, in her final film before her death, handles the intense material with fitting gravitas, transforming a bleak survival tale into a meditation on faith, betrayal, and martyrdom. The whole thing has a religious and mystical edge, one that angered the Soviet authorities, who even considered banning the movie.

The visuals complement the themes. Here, stark black-and-white cinematography freezes time as much as it captures it. The faces are raw, cracked by cold and fear. While there is violence, the real battles are internal, the struggle for the soul. Boris Plotnikov and Vladimir Gostyukhin give committed, elemental performances, playing men stripped to their last beliefs. For all these reasons, The Ascent becomes an endurance test, but a valuable one.

The Ascent

Release Date

April 2, 1977

Runtime

1h 51m

9

‘Fires on the Plain’ (1959)

Directed by Kon Ichikawa

“There is no tomorrow, only today.” Set in the final days of World War II in the Philippines, Fires on the Plain follows a starving Japanese soldier (Eiji Funakoshi), tubercular, abandoned, and wandering a landscape of ash, maggots, and cannibalism. Through this character, Kon Ichikawa delivers one of the bleakest visions of war ever committed to film, and he does it without blinking. Rather than being dramatic, the combat scenes are simply pitiful. Emaciated bodies crumple without ceremony. Human beings are reduced to scavengers.

There’s no glory, no victory, not even camaraderie. Just the long, painful unraveling of civilization. Funakoshi plays the lead with vacant eyes and trembling restraint, embodying a man who keeps walking only because dying takes effort. This is war as entropy. And yet, somehow, it’s still kind of beautiful at times. There are weirdly tranquil moments amid the grimness. Sunlight on bone, silence after a scream.

8

‘Go Tell the Spartans’ (1978)

Directed by Ted Post

“In this war, the body count is all that matters.” Go Tell the Spartans is a grim, underseen Vietnam War drama that’s almost as bitter and incisive as Platoon or Apocalypse Now. Set in 1964, before full U.S. involvement, it tells the story of a small American outpost tasked with holding a meaningless village. Burt Lancaster plays the weary commander, a man who already knows the whole war is doomed. His is a world of bureaucratic procedures, miscommunication, and creeping futility.

This is a war story told with blunt honesty, avoiding stylization in favor of dry rot realism. The soldier characters are more placeholders than warriors. Lancaster is phenomenal here, hollow-eyed and dour, trying to do his duty even as the entire premise of the mission unravels around him. The title is a reference to the famous last stand of Leonidas’ Spartans against Xerxes, but there are no heroes in this story. Just warnings unheeded, and blood spilled for abstractions.

Go Tell the Spartans

Release Date

July 12, 1978

Runtime

114 minutes

Cast

Burt Lancaster

Maj. Asa Barker

Craig Wasson

Cpl. Courcey

Marc Singer

Capt. Alfred Olivetti

Joe Unger

Lt. Raymond Hamilton

7

‘The Steel Helmet’ (1951)

Directed by Samuel Fuller

“You left your rifle in a church?!” The Steel Helmet was the first American film about the Korean War, and it still might be the boldest. Shot in just ten days on a shoestring budget, Samuel Fuller’s gritty, no-nonsense war drama pulls no punches. It opens with a lone GI surviving an ambush, and from there, it spirals into a hellish portrait of war as confusion, hypocrisy, and unresolved trauma. Gene Evans, in a career-defining role, plays Sgt. Zack as a brute with a brain, half feral and half father figure.

As a whole, this is a lean, mean film with more guts than many made decades later. Fuller, a World War II vet himself, makes every line count and every silence loud. The dialogue is sharp, the violence abrupt, and the morality murky. The film also features one of cinema’s first integrated fighting units, and it doesn’t shy away from mid-20th-century America’s racial contradictions, even in uniform.

Release Date

February 2, 1951

Runtime

85 Minutes

Director

Samuel Fuller

Writers

Samuel Fuller

6

‘Cross of Iron’ (1977)

Directed by Sam Peckinpah

“I believe God is a sadist, but probably doesn’t even know it.” With Cross of Iron, Sam Peckinpah, best known for stylized slow-motion carnage, turned his gaze to World War II and produced something startlingly bleak and weirdly tender. Switching things up a little, the movie is told from the German side, not with sympathy, but with existential disgust. James Coburn leads the cast as Steiner, a battle-hardened soldier trying to survive both the Soviets and the incompetence of his own superiors.

Coburn lumbers through it all with a sniper’s glare and a philosopher’s bitterness. Opposite him, Maximilian Schell plays the aristocratic officer who wants glory and gets humiliation. Peckinpah’s violence is characteristically explosive, but, once again, it’s never triumphant. Bodies fall and blood spatters, but everything feels drained of meaning. Perhaps unsurprisingly, Cross of Iron was a box office flop, but was embraced by filmmakers like Orson Welles and Quentin Tarantino.

Release Date

May 20, 1977

Runtime

119 Minutes

Director

Sam Peckinpah

Writers

Willi Heinrich, James Hamilton, Walter Kelley, Julius J. Epstein

5

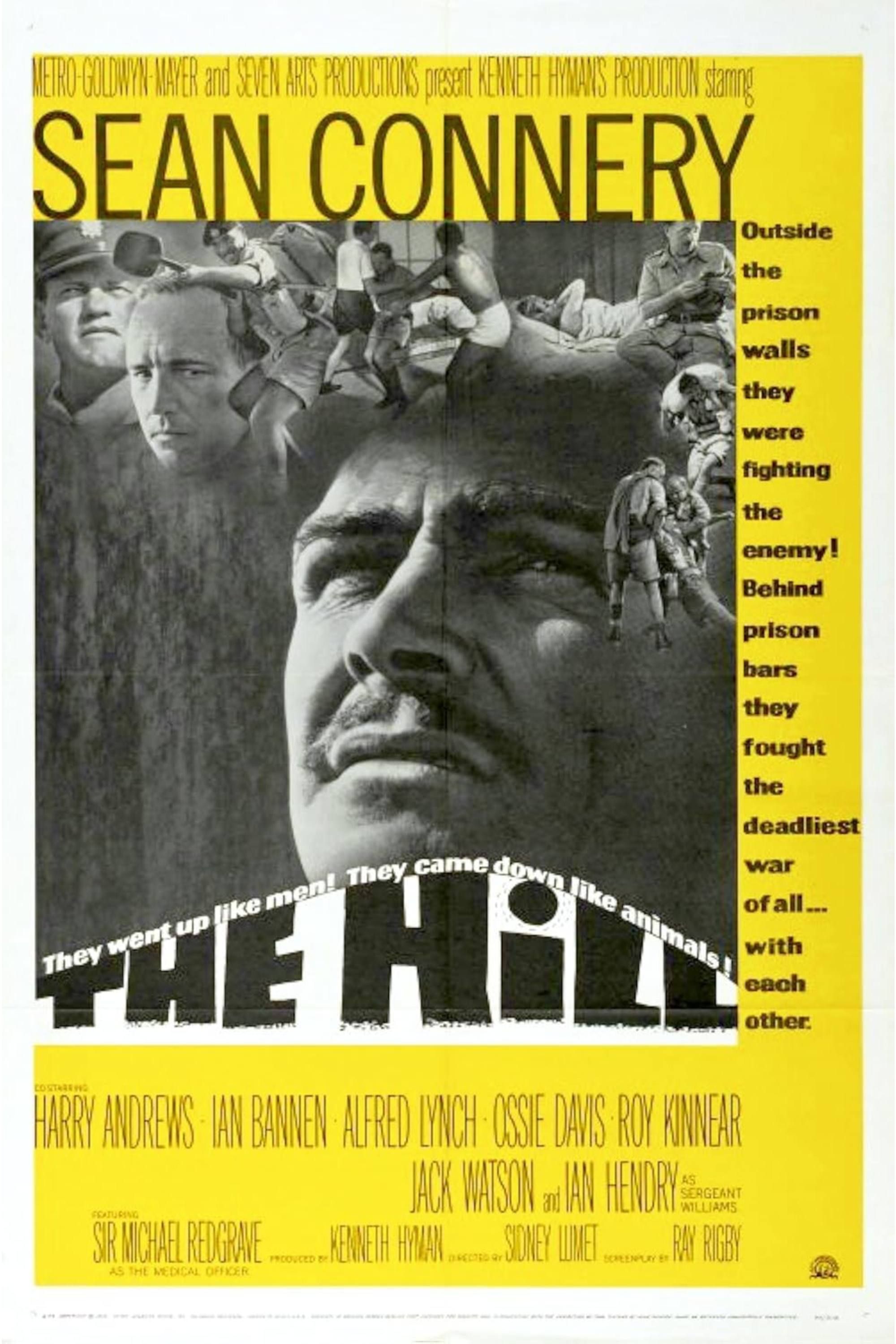

‘The Hill’ (1965)

Directed by Sidney Lumet

“What the hell is this, a war or a lunatic asylum?” Not a single shot is fired in combat, and yet The Hill is still an incredibly angry movie, even by the genre’s standards. Set in a British military prison in North Africa during World War II, it introduces us to a group of soldiers broken by authority, routine, and heat. The titular hill is a man-made mound of sand the prisoners are forced to climb again and again until their bodies give out. Through them, the movie comments on institutional cruelty and systemic dehumanization.

Acting-wise, Sean Connery, shedding his James Bond charm, gives one of the most searing performances of his career. He’s not suave, he’s furious. And rightfully so. He’s being ground down by slow, bureaucratic, relentless violence. Sidney Lumet shoots his travails with blistering intensity, using harsh sunlight and tilted angles to mirror the psychological breakdown of the characters.

Release Date

October 3, 1965

Runtime

123 Minutes

Writers

Ray Rigby

4

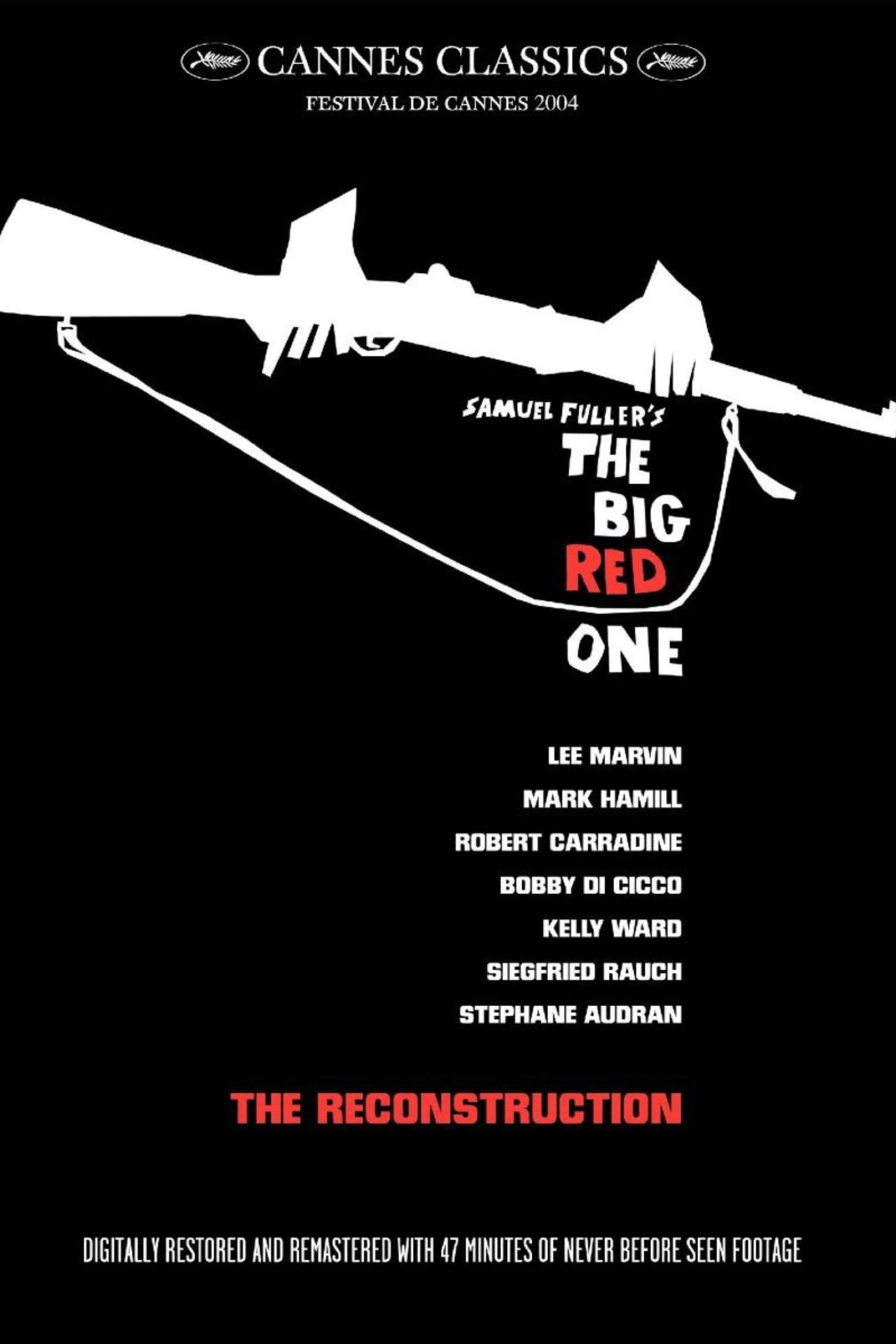

‘The Big Red One’ (1980)

Directed by Samuel Fuller

“You don’t murder animals. You kill ’em.” Samuel Fuller returned to the war genre three decades after The Steel Helmet with this deeply personal, semi-autobiographical odyssey about a unit of American infantrymen in World War II. The Big Red One isn’t flashy. It’s episodic, sometimes uneven, but it has a lot to say. Here, war is reduced to a series of absurd, horrifying, and sometimes eerily quiet moments stitched together by death.

The story focuses on a hardened sergeant (played with weary grace by Lee Marvin) and four young soldiers from North Africa to D-Day to the liberation of a concentration camp. Along the way, they joke, freeze, kill, and survive. That’s it. Survive. Fuller, who lived it, doesn’t offer grand speeches or moral epiphanies. He shows how war shrinks you into instinct. A longer director’s cut, released in 2004, reveals just how ambitious and emotional Fuller’s vision really was.

Release Date

July 18, 1980

Runtime

113 Minutes

Director

Samuel Fuller

Writers

Samuel Fuller

3

‘Tae Guk Gi: The Brotherhood of War’ (2004)

Directed by Kang Je-gyu

“If I become a soldier, they’ll let you stay behind.” Tae Guk Gi is often described as a kind of South Korean take on Saving Private Ryan for its scale and intensity. In reality, it’s pretty different, less a war movie than a family tragedy written in blood. The story is about two brothers forcibly conscripted into the South Korean army during the Korean War. One becomes a reluctant hero to protect the other. But as the violence escalates, so does the moral collapse. Notably, the movie shows acts of brutality carried out by both the North and the South.

Director Kang Je-gyu handles the narrative with a sweeping, gut-wrenching, and human touch, never losing sight of the human cost. While the action is thunderous, it’s the brothers’ bond that carries the emotional weight. Jang Dong-gun, in particular, gives a performance of stunning range, moving from protective older sibling to hollow-eyed instrument of war.

2

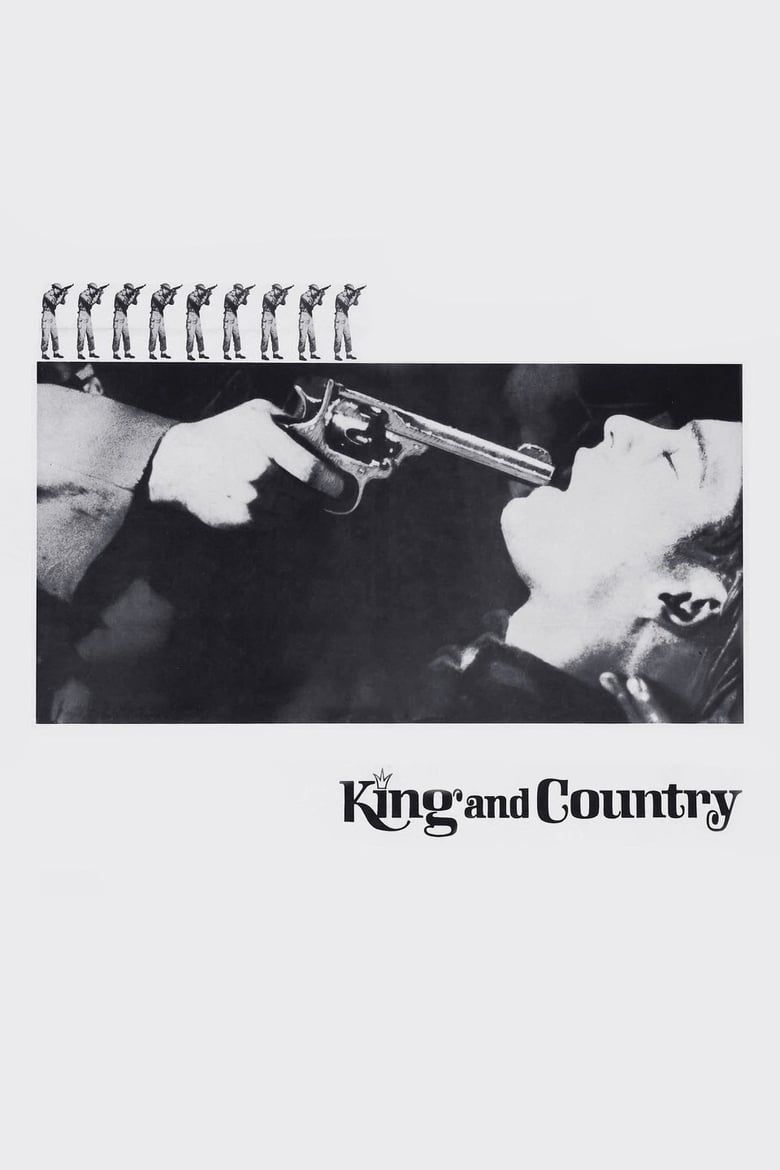

‘King and Country’ (1964)

Directed by Joseph Losey

“Do you want me to say he’s sane, sir? Do you want me to lie?” King and Country is small in scale but devastating in effect. Set during World War I, it centers on a British soldier accused of desertion and the officer assigned to defend him. What begins as a court martial becomes an indictment of military justice, the meaning of sanity, and the way institutions destroy individuals to preserve appearances. It stands apart from most in the genre by being a war movie with no battlefield.

Tom Courtenay plays the accused with a broken, shell-shocked fragility, while Dirk Bogarde slowly peels away his own complicity in the system. The stars are assisted by fittingly spare and suffocating direction from Joseph Losey. The trenches become a prison. Silence becomes an accusation. The final moments are as quiet as they are damning. Dulce et decorum est pro patria mori.

Release Date

September 5, 1964

Runtime

85 minutes

Director

Joseph Losey

Writers

Dirk Bogarde, Evan Jones, J.L. Hodson

1

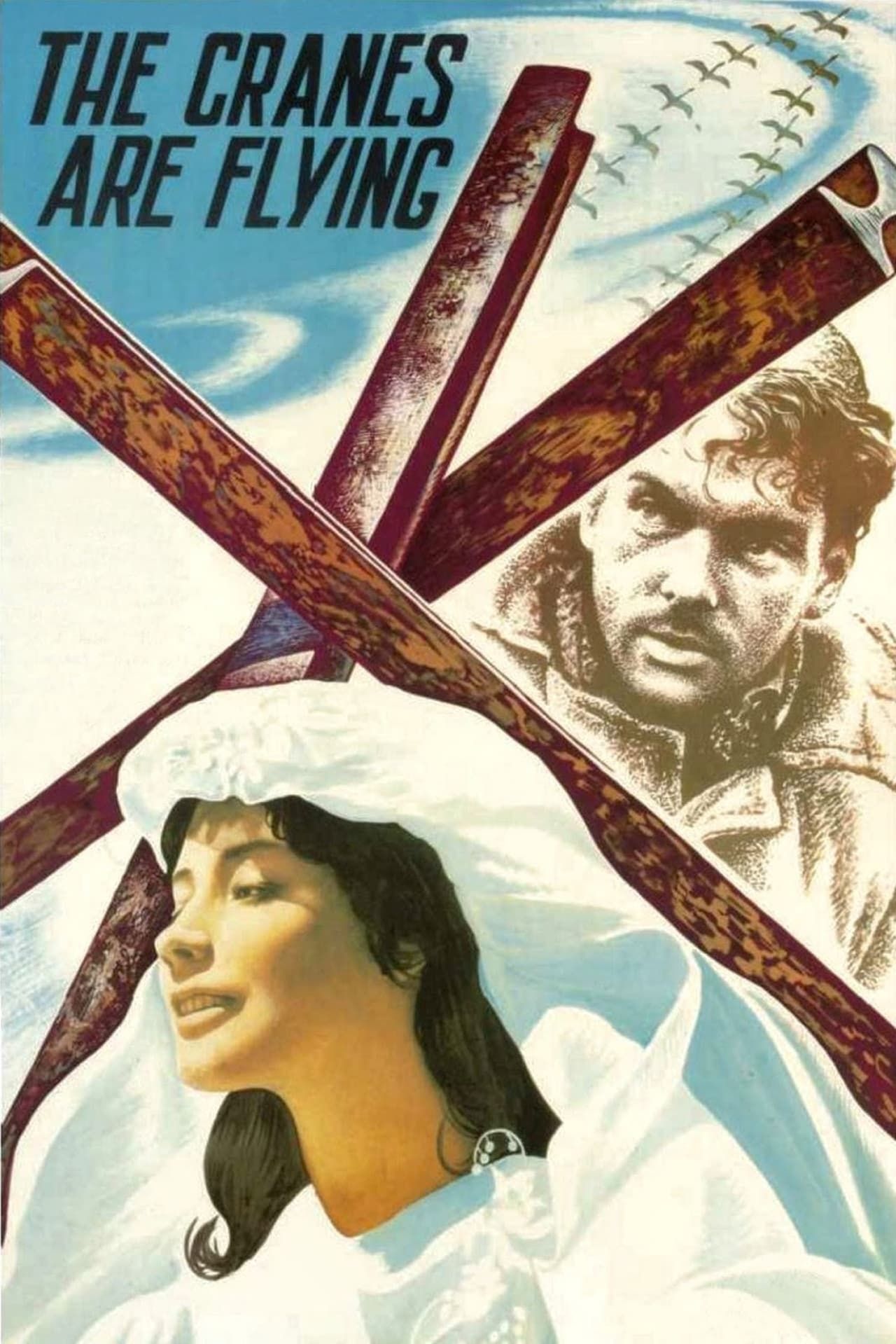

‘The Cranes Are Flying’ (1957)

Directed by Mikhail Kalatozov

“I told you I’d come back. Even if they killed me, I’d come back.” The Cranes Are Flying is one of the masterpieces of Soviet cinema. Set during World War II, it tells the story of a young couple (played by Tatiana Samoilova and Aleksey Batalov) torn apart when the man volunteers for the front and never returns. From here, the movie expands into a portrait of grief, guilt, and resilience, carried almost entirely by the astonishing performance from Samoilova.

In terms of the aesthetics, Mikhail Kalatozov’s camera hums with energy, serving up tracking shots, overhead spins, and hallucinatory images. Yet the visuals never overpower the sorrow. The film dares to show the pain not just of death, but of hope denied. Of waiting, and losing, and learning how to live in ruins. At Cannes, it won the Palme d’Or, but it’s kind of faded from the general conversation. Fans of more artful, contemplative war dramas should check it out.

Release Date

October 12, 1957

Runtime

97 Minutes

Director

Mikhail Kalatozov

Writers

Viktor Rozov

NEXT: Sue Me, but I Think a Remake of These 10 Classics Would Actually Be Great